Readers,

At last, here’s that interview with author John Irving that I promised. You can watch the video up above, and you can read a transcript of our conversation down below, past his Oldster Questionnaire. ⬇️

First a word about the latter: Irving initially wasn’t interested in taking The Oldster Magazine Questionnaire, but somehow I persuaded him to indulge me. As a result, some of his responses are rather short and feisty. I can take it! He made me laugh.

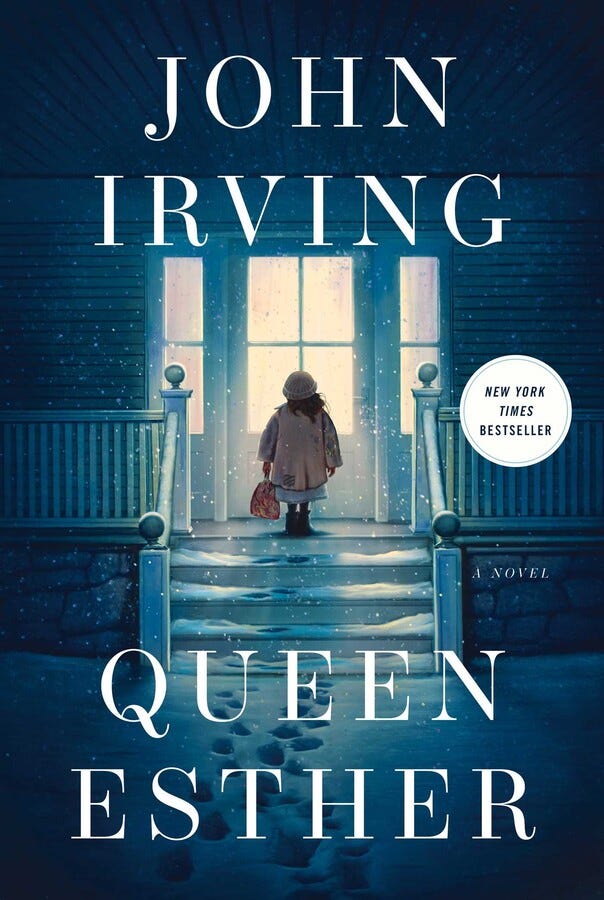

I felt so thrilled and honored when I was offered the opportunity to interview Irving about Queen Esther, his latest novel—his 16th—released in November, and already a New York Times bestseller.

I’m a long-time fan of his books. The World According to Garp was one of the first grown-up novels I ever read, when I was 15 or so, and I just loved it. (As I confess in the interview, I felt particularly adult reading it at that age because of the dirty parts.) I devoured The Hotel New Hampshire a few years later. I’ve read most of Irving’s other novels, and it’s hard to pick a favorite. I’ve loved them for their compellingly quirky, often marginalized characters, and the way he weaves them into the world history and social issues of their times; their unusual family configurations; their blend of poignance and humor; and of course Irving’s brilliant, absorbing writing.

In Queen Esther, Irving fans will recognize a few characters, most notably Dr. Wilbur Larch, whom we first encountered in The Cider House Rules, and a familiar setting—the orphanage in St. Cloud’s, Maine. The book introduces us to a new “unadoptable orphan,” Esther Nacht, a Jewish girl whose father dies en route to the United States from Vienna, and whose mother is murdered by anti-Semites in Portland Maine. When we first meet Esther, in the early 20th Century, she’s just 4. The story ends in 1981, when she is 76. Here’s a brief introduction to Queen Esther from Irving’s website:

For readers or moviegoers who know The Cider House Rules, a familiar character reappears in Queen Esther—John Irving’s sixteenth novel. Dr. Wilbur Larch is younger than you remember him, and the unadopted orphans at St. Cloud’s are a different cast of characters—a Viennese-born Jew, Esther Nacht, among them. Like The Cider House Rules, Queen Esther is a historical novel with a political theme. Anti-Semitism shapes Esther’s life, not only in Vienna. Esther’s story is fated to intersect with Israel’s history.

The cover art depicts the orphanage in St. Cloud’s, Maine, where Esther, who is not yet four, is abandoned one winter night. Esther is born in Vienna in 1905. Her father dies on board the ship from Bremerhaven to Portland, Maine; her mother is murdered by anti-Semites in Portland. At St. Cloud’s, it’s clear to Dr. Larch that the abandoned child not only knows she’s Jewish; she’s familiar with the biblical Queen Esther she was named for. Dr. Larch knows it won’t be easy to find a family who’ll adopt Esther.

When Esther is fourteen, about to become a ward of the state, Dr. Larch meets the Winslows—a philanthropic family with a history of providing for unadopted orphans. The Winslows aren’t anti-Semitic—nor are they Jewish. Esther is enduringly grateful. While she retraces her steps to her birth city, Esther never stops loving and protecting the Winslows—not even in Vienna. In the final chapter of this historical novel—set in Jerusalem, in 1981—Esther Nacht is seventy-six.

I so enjoyed talking with Irving. He was kind and warm, and generous with his time.

We talked about Queen Esther; Irving’s love for Dickens, Melville, and the 19th Century novel; the way he uses some of his life experiences as scaffolding for his stories, but then departs significantly from reality by inventing a lot; how, as a rule, he doesn’t begin writing until he knows the ending he wants to aim toward; and his allyship toward various marginalized groups, which shows up again and again in his characters and plots.

Whether you watch it above or read it below, I hope you enjoy our conversation! - Sari

PS Just below is his Oldster Magazine Questionnaire, and below that is the transcript of our interview. ⬇️

This is 83: Author John Irving Responds to The Oldster Magazine Questionnaire

“I never had a bucket list. I got to be what I wanted to be—a full-time writer.”

From the time I was 10, I’ve been obsessed with what it means to grow older. I’m curious about what it means to others, of all ages, and so I invite them to take “The Oldster Magazine Questionnaire.”

Sometimes you’ll find responses from writers, musicians, and artists you’ve heard of—like Kate Pierson, Neko Case, Rosie O’Donnell, Ava Duvernay, Jerry Saltz, Lucy Sante, Ricki Lake, Hilma Wolitzer, Elizabeth Gilbert, Judith Viorst, Cheryl Strayed, Deesha Philyaw, Chloe Caldwell, etc.—but more often it will be people (of all ages) you haven’t heard of, Humans of New York-style.

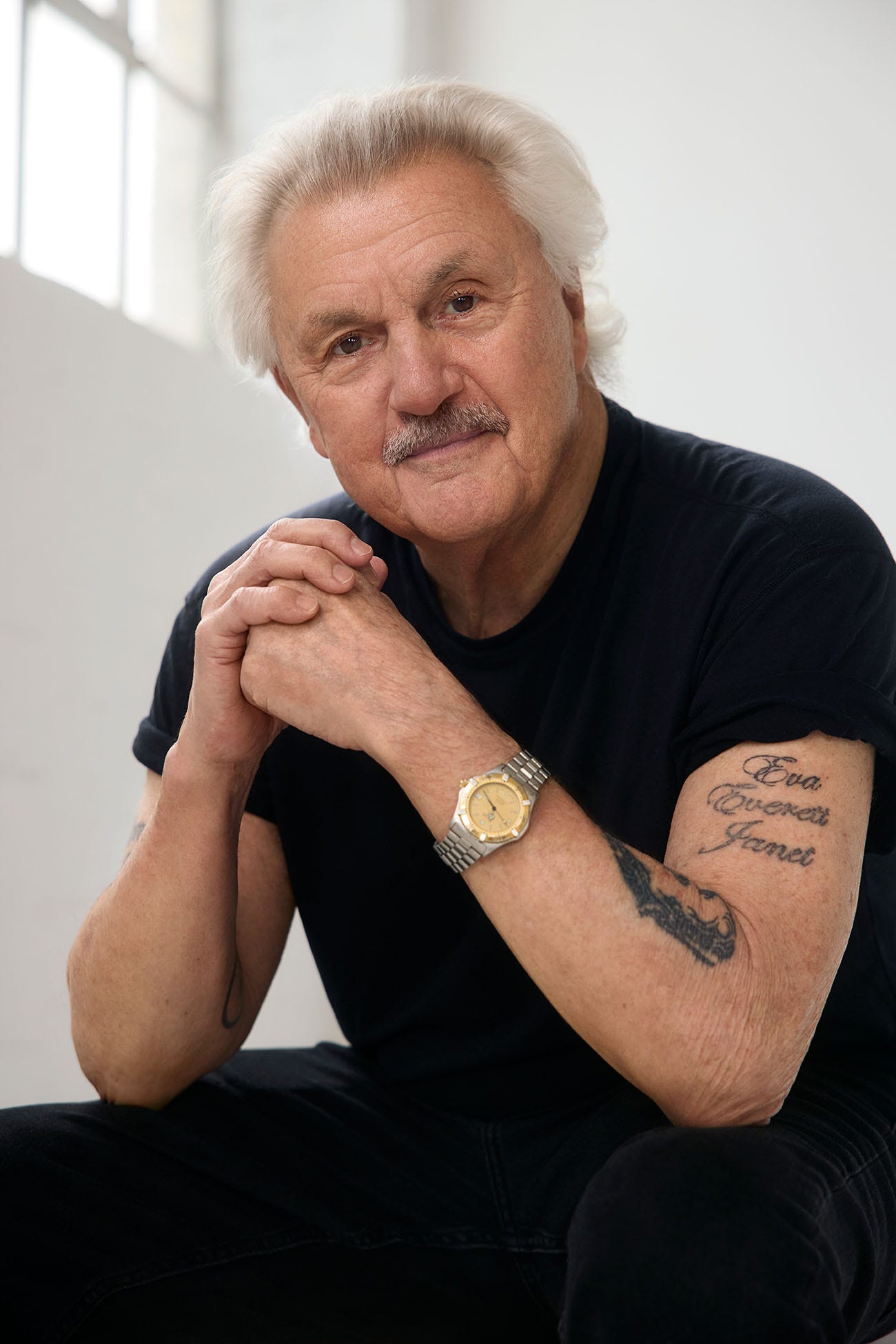

Here, celebrated, award-winning novelist and screenwriter John Irving—whose latest novel is Queen Esther—responds. -Sari Botton

PS If you’re enjoying the work I do here at Oldster, please consider supporting it by becoming a paid subscriber. 🙏

“Oldster Magazine fills a void. I look forward to reading it on a regular basis.” - Alexandra Grabbe, paid subscriber.

John Irving was born in Exeter, New Hampshire, in 1942. He was 15 when he knew he wanted to be a novelist. He started his first novel in 1965, when he was 23. It was published in 1968, when he was 26. His 16th novel was published this month. He’s been writing novels for 60 years.

—

How old are you?

83.

Is there another age you associate with yourself in your mind? If so, what is it? And why, do you think?

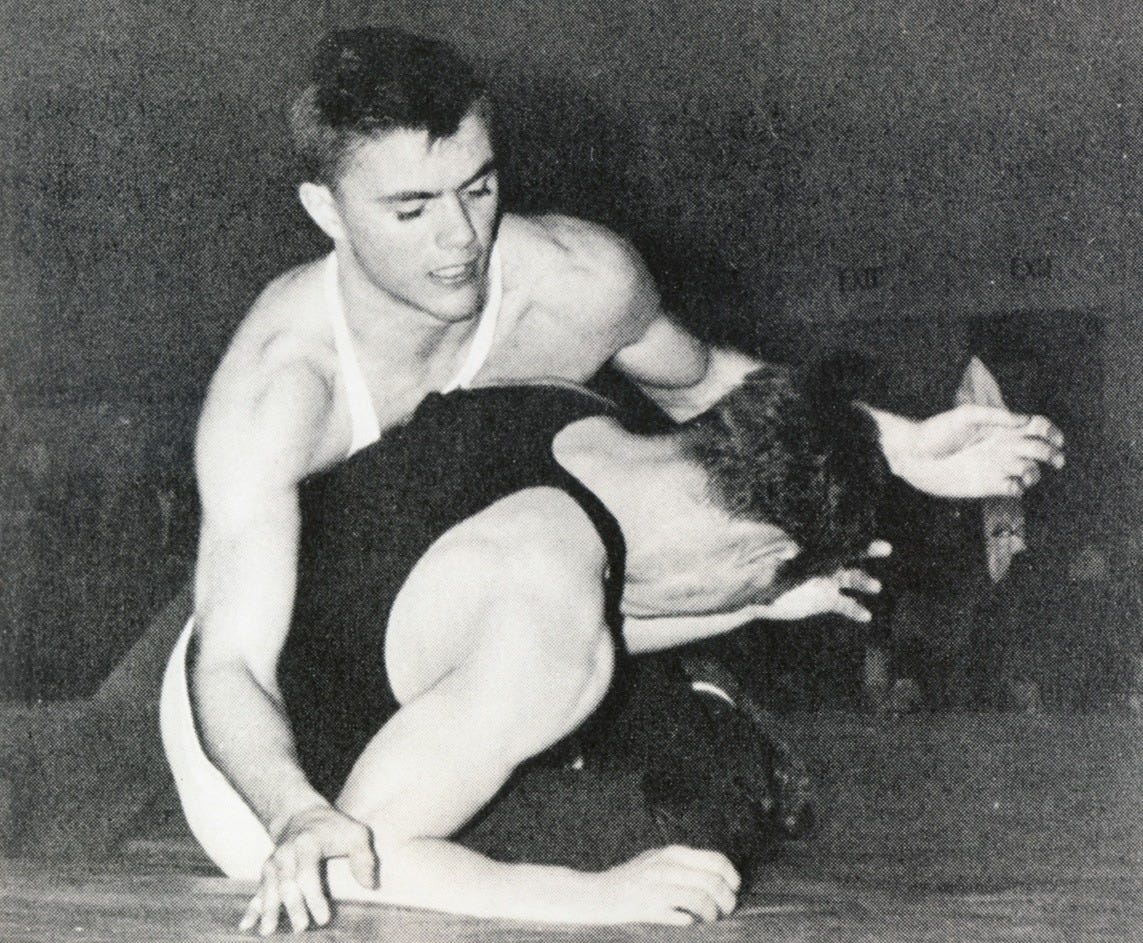

Thinking about your age is a waste of time—it’s like thinking about your ancestors. You can’t change who your ancestors were, or how old you are. I think about the things I can do something about. After a wrestling match I lost, my wrestling coach saw me feeling sorry for myself. “Self-pity is just another word for doing nothing, Johnny,” he said.

Only as a wrestler was I ever in competition with my peers. My coaches taught me that I could learn from my limitations; if I knew my weaknesses, I could try to improve and defend myself. The key word is “try.”

Do you feel old for your age? Young for your age? Just right?

When I was diagnosed with prostate cancer, I chose the radical prostatectomy. The possible side-effects of this surgery didn’t concern me. Death was a possible side-effect of not choosing the surgery. One day, I’ll die of something I can’t do anything about, but I won’t die of prostate cancer.

Are you in step with your peers?

Charles Dickens was the writer who made me want to be a novelist, only if I could be like him. Herman Melville taught me to know the end of my novel before I began writing it. They were never my “peers.” The 19th-century novel was (and remains) the model of the form for me. Only as a wrestler, was I ever in competition with my peers. My coaches taught me that I could learn from my limitations; if I knew my weaknesses, I could try to improve and defend myself. The key word is “try.”

What do you like about being your age?

I like not being dead. I like being able to walk a couple of miles every day.

What is difficult about being your age?

My 2020 spinal compression fracture was difficult. The resultant orthopedic therapy has been difficult, but it’s working. I’m getting better.

What is surprising about being your age, or different from what you expected, based on what you were told?

Again: nothing is accomplished by thinking about what you can’t change.

When I was diagnosed with prostate cancer, I chose the radical prostatectomy. The possible side-effects of this surgery didn’t concern me. Death was a possible side-effect of not choosing the surgery. One day, I’ll die of something I can’t do anything about, but I won’t die of prostate cancer.

What has aging given you? Taken away from you?

I haven’t stopped exercising, but my exercise is constantly being adjusted.

How has getting older affected your sense of yourself, or your identity?

My sense of myself, or my identity, isn’t age-related. I’m busy with the promotion part of publishing a 16th novel, while I’m more interested in continuing to write my 17th novel, which I’ve begun. I’ve learned that I would rather be writing a novel than talking about writing, but I understand that talking about writing is a necessary part of the process.

What are some age-related milestones you are looking forward to?

If the round numbers are what you mean by “milestones,” they mean nothing to me. Staying as healthy as I can be, exercising and writing and being with my family—the essential things aren’t “age-related” to me.

Or ones you “missed,” and might try to reach later, off-schedule, according to our culture and its expectations?

“Our culture and its expectations” are of no interest to me!

What has been your favorite age so far, and why?

Staying active and alive aren’t associated with a favorite age. You are the age you are!

Would you go back to this age if you could?

Except in so-called Science Fiction, going back isn’t an option.

Is there someone who is older than you, who makes growing older inspiring to you?

No.

My sense of myself, or my identity, isn’t age-related. I’m busy with the promotion part of publishing a 16th novel, while I’m more interested in continuing to write my 17th novel, which I’ve begun. I’ve learned that I would rather be writing a novel than talking about writing, but I understand that talking about writing is a necessary part of the process.

Who is your aging idol and why?

Dickens died when he was 58. Poor Melville had a miserable life. They are my heroes—not because of how long they lived, or how happily (or unhappily), but because of what wonderful novels they wrote. My idols have nothing to do with age.

What aging-related adjustments have you recently made, style-wise, beauty-wise, health-wise?

My wife and children would be laughing about the “aging-related adjustments” I’ve made, especially concerning the “style-wise” and “beauty-wise” considerations. When I left my house in Vermont and moved full-time to Toronto (in 2015), I brought all my ski clothes and flannel shirts with me; they’re useful in Toronto, too. The “nice” clothes I have are birthday and Christmas presents from my wife and children. Writers don’t have to dress up a lot. As for “health-wise,” I think my earlier answers have addressed this.

What’s an aging-related adjustment you refuse to make, and why?

I’m not going to repeat how little I think about (or care about) “age.”

What turn of events had the biggest impact on your life?

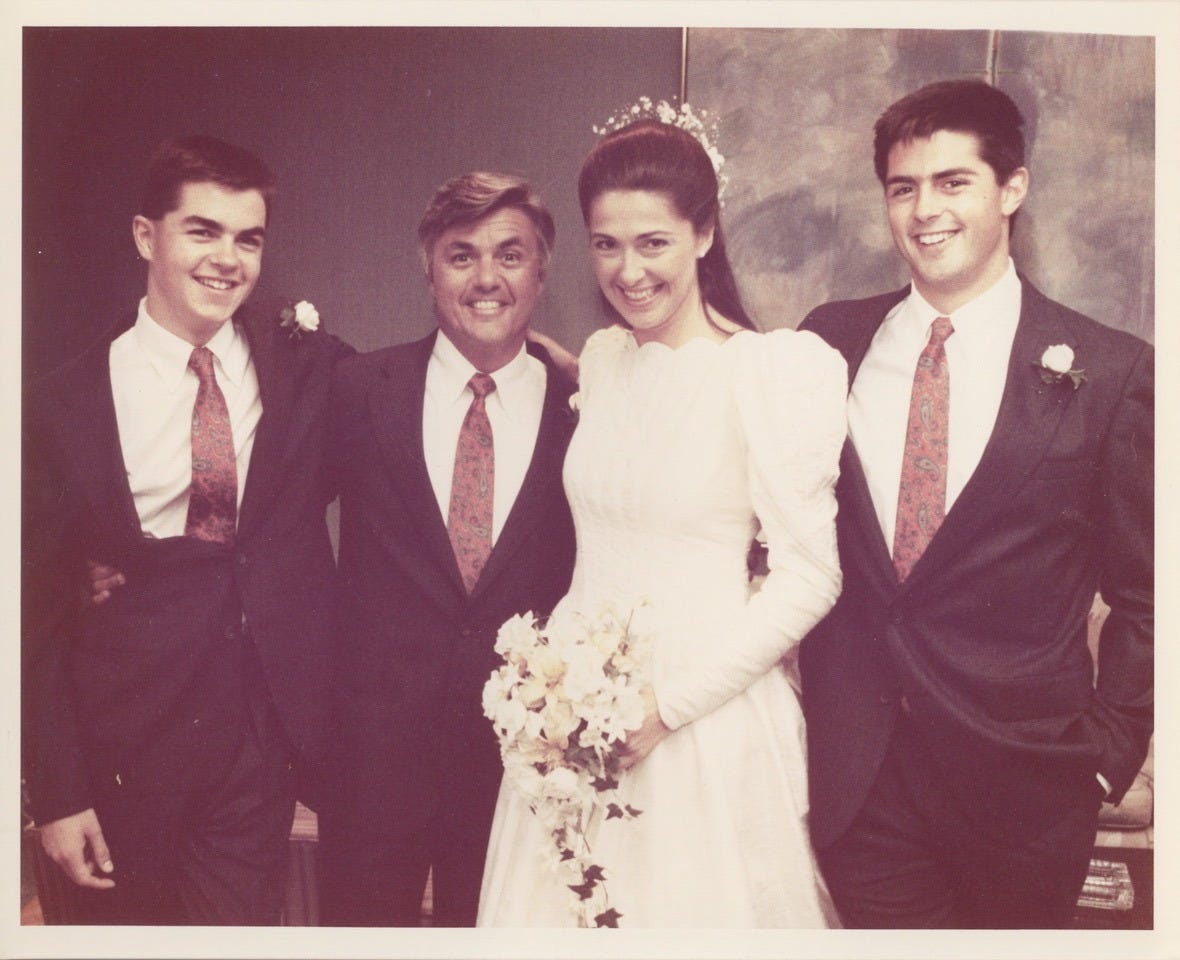

Having children, being a father—especially being a father for the first time, when I had not yet graduated from college. If I’d never had children, I can’t imagine what I would have written about. Certainly being a father is what gave me the subject of being afraid for those you love.

What took your life in a different direction, for better or worse?

Meeting my second wife took my life in a better direction.

What is your number one regret in life?

Regret is just another word for self-pity. I’ve told you what my wrestling coach said about self-pity.

If you could do it all over again, what is the biggest thing you’d do differently?

I don’t write Science Fiction.

What is high up on your “bucket list?”

I never had a bucket list. I got to be what I wanted to be—a full-time writer.

What do you hope to achieve, attain, or plain enjoy before you die?

I want to keep doing what I’m doing.

Is there a piece of advice you were given, that you live by?

Don’t make me repeat what my wrestling coach said.

If so, what was it, and who offered it to you?

Don’t make me repeat what my wrestling coach said.

Charles Dickens was the writer who made me want to be a novelist, only if I could be like him. Herman Melville taught me to know the end of my novel before I began writing it. The 19th-century novel was (and remains) the model of the form for me...Dickens died when he was 58. Poor Melville had a miserable life. They are my heroes—not because of how long they lived, or how happily (or unhappily), but because of what wonderful novels they wrote.

What are your plans for your body when you’re done using it? Burial? Cremation? Body Farm? Other?

This choice should be made by my wife and children. I’ve already told my wife, who is much younger than I am, to do with me what’s easiest for her. What do I care? I just don’t want to be a burden to my loved ones. (I have suggested that some of my ashes could be scattered where we scattered the ashes of a beloved dog.)

How do you feel about dying?

I’ve read about it, I’ve written about it, I’m aware it happens.

And what do you expect to happen to your “soul” or “spirit” after you die?

Oh, please. Dead is dead. I just hope people keep reading me, after I’m gone, but I have no control over that.

What’s your philosophy on celebrating birthdays as an adult? How do you celebrate yours?

Again, I leave that decision to my wife and kids. I’ll do whatever they want to do. A “philosophy” on celebrating birthdays? Who has the time to think about such things?

Check out all the Oldster interviews…

Below here is the transcript of our conversation. ⬇️

My holiday gift to you: Now through New Year’s Eve, save 20% off paid annual subscriptions. Paid subscriptions keep Oldster going, and allow me to pay essayists and interviewers.

An Interview with John Irving.

On his latest novel, “Queen Esther,” and his approach to writing. And some answers to questions that readers submitted.

Sari Botton:

Welcome to the Oldster Magazine Show. Today, my guest is John Irving, the celebrated novelist who has published now 16 books. You have probably read some of his most famous books, The World According to Garp, The Cider House Rules, A Prayer for Owen Meany. He has just published Queen Esther. John, will you hold up the book? Yes. An epic coming of age novel that is really incredible and I’m so grateful that you’re here to speak with us. He’s an award-winning not only novelist, but also screenwriter. He’s written the screenplays for some of his movies, which I just love. Welcome, John.

John Irving:

Thank you very much.

Sari Botton:

It’s so good to have you here. So let’s dive right in. You just published Queen Esther, which revisits some of the characters and a setting from an earlier book, The Cider House Rules. Most notably, Dr. Wilbur Larch, the obstetrician who runs an orphanage at St. Cloud’s in Maine. But at an earlier time, he’s younger in this book than he is in The Cider House Rules. And there we meet an orphan, Esther Nacht, who is, I would say, one of the two protagonists of the novel, along with her biological son, Jimmy Winslow. When did you start the book and how long did it take to write? Is it like 450 pages or 500 pages?

John Irving:

It is a novel of probably slightly longer than average length for literary fiction today. But for my readers, it’s a short one. For readers who are familiar with my novels, it’s a much shorter novel for me. And like all of my novels, they exist as a storyline, a cast of characters, a complete plot until I know what the end is. And I never start a novel until I know what the last chapter is. And I usually know more about that last chapter than I do about where I’m going to begin. But it’s always the case with my novels that they accumulate pages for several years longer than it will ever take me to write them once I begin. Because by the time I begin, my process of needing to know the ending first means that I’ve already taken a lot of notes about them, especially because I’m an ending-driven writer and I’m writing toward a preconceived ending.

In this novel’s case, it was not only shorter, but much easier for me because as you mentioned, in this case, I also knew much more about the beginning of the novel than I normally know. Because the beginning of the novel, as you say, is in very familiar territory, the orphanage in St. Cloud’s Maine and with a very familiar character to me and to my readers, Dr. Larch. I knew that that was where my Jewish orphan would be abandoned and I knew exactly when. This novel ends in Jerusalem in 1981 when Esther Nacht is 76. And I was always building a timeline for her in reverse. She’s a Viennese-born Jew in 1905. By the time she’s almost four and is an orphan in Maine, her life has already been shaped, formed, constructed by antisemitism.

Sari Botton:

Yes, both of her parents were murdered.

John Irving:

Yes.

Sari Botton:

Her father in Europe and her mother in Portland, Maine?

John Irving:

Maine.

Sari Botton:

Yeah. So I guess it probably took you... You said it was a shorter process this time. How long ago did you start it?

John Irving:

This novel was only three years in the writing. That’s short for me.

Sari Botton:

Wow.

John Irving:

Three, it was slightly under four, slightly more than three, but less than four. That’s a short period of time for me. But again, it existed. It lived as a novel in progress for a decade probably before I started it. I mean, it was there waiting to be written. But once I began, it was a much quicker process than usual for me.

I never start a novel until I know what the last chapter is. And I usually know more about that last chapter than I do about where I’m going to begin. But it’s always the case with my novels that they accumulate pages for several years longer than it will ever take me to write them once I begin. Because by the time I begin, my process of needing to know the ending first means that I’ve already taken a lot of notes about them, especially because I’m an ending-driven writer and I’m writing toward a preconceived ending.

Sari Botton:

Yeah. Queen Esther is very much about antisemitism and fighting it in Israel and in Europe and in the US. And it’s interesting because it is out now two years after the October 7th attack and what’s happened in Gaza. But it sounds like you had this on your mind for a long time before that.

John Irving:

Yes.

Sari Botton:

So what drew you to that theme of fighting antisemitism and to the Purim story, which is about Queen Esther, a different Queen Esther who saves the Jews. Yeah. What drew you to that?

John Irving:

Well, it was always my intention to create an empathetic character that readers would love and understand who is one of those early European-born Jews who will be one of the Zionists who is part of the founding of the state of Israel. It was always my intention to create a completely sympathetic character who will become one of those people. A founder, an important cog in the founding of the state of Israel. One of those many European Jews who got out of Europe in time and were part of that process. And I also recognize, knowing my story’s narrative timeline, born in Vienna in 1905, Esther is not yet four when she’s dumped at the orphanage in St. Cloud. She knows she’s Jewish and she knows all about the Esther she is named for.

But for all the years she will be in the orphanage, and I couldn’t imagine a more unadoptable child, which was my intention to make her one of the orphanage’s most unadoptable child. No one is inclined to adopt a child who is old enough to know anything about her history, especially a history as dark as Esther’s, not going to happen.

Sari Botton:

She knows from a very young age, and she’s very verbal, and she’s really... I guess the trauma that she experienced probably made her as articulate as she was at a young-

John Irving:

I knew she was in sympathetic hands at the orphanage. I knew that in Dr. Larch’s estimation, she would definitely be one of the best ones, and that he would do everything in his power to find out as much as he could about her, knowing that she’s going to be there until she’s 14, going on 15, a ward of the state. All of this was intentional because I wanted this kid, this Viennese-born Jew, I wanted her to be dedicated to make up for the Jewish childhood she had been denied, the Jewish childhood that was stolen from her. I wanted her to have an agenda to retrace and reconnect with her Jewishness. And she finds a family, not Jewish, clueless about Judaism, but an empathetic family who will provide her with the education to-

Sari Botton:

Then you got two other couples.

John Irving:

... to be independent.

Sari Botton:

Yes. And you’ve got two other couples in her realm who are Jewish, one more religious, one less religious who influenced her. They bring her into Esther’s life so that she has-

John Irving:

No, they connect. And of course, it was also a part of my plan to send my poor character, Esther, in the wrong direction at the wrong time. When Esther goes back to her birth city and everyone wants to know where they come from. Esther is no different than anyone else. She was born in Vienna and she wants to go to Vienna. But at the time she goes to Vienna in the 1930s, most Viennese Jews have either left or in the process of leaving. And I wanted Esther to be going the wrong way and to therefore connect with those people who are also going, particularly speaking of where she came from, really came from, most originally, most historically, to the land of Judah, the land of the Israelites. I wanted to make her, especially at a time, and for a long time now, when Zionism has fallen into such criticism and disfavor.

I said, well, I always knew a historical reason to be most empathetic, most sympathetic to that instinct, to go to the land of Judah, to have a place where you could at least not be safe, but defend yourself. I understood that. I understood that from history. I understood that even from my first experience in Israel, which I purposely made my character, Jimmy Winslow’s only experience in Israel in April of 1981.

Sari Botton:

Yes, a book festival. And was it 1981 when you went to the book festival?

John Irving:

It was April of 1981. And I went for an interesting combination of reasons, which are reflected in the novel in part. I made Jimmy’s experience, Jimmy being the birth child of Esther, but she’s never been a mother he’s known or even remembers. Another woman raised him and was the only mother he knew, but he knows his story. He knows who his birth mother was. And just as everyone is curious about where they came from, well, he would like to see her. He would like to find her. Well, in my case, my first European publishers, the first European publishers whoever bought my work and translated me were European Jews with longstanding ties to Israel. They were the first European publishers I had who introduced me to all the other ones because of their good reputations in the European publishing community.

My Swedish publisher and my French publisher were European Jews with longstanding ties to Israel, longstanding connections to Israel. I had an Israeli publisher because of them, because of them. And when my Israeli publisher and what was then called the Jerusalem International Book Festival or Book Fair, I forget, when I was invited to Jerusalem in 1981, these European publishers said, “Oh, we’ll come with you. We know what goes on there.” And so I was in their companionship the whole time I was there. And it was always my intention. If you think about how many of my novels are historical and how often the historical ones are often the most political ones, that goes together. Well, the sensation I had, the overriding feeling I had when I left Israel for the first time in April of ‘81 was that the conflict I had seen developing looked eternal or everlasting to me.

I had that sense of foreshadow or foreboding that this conflict was not only going to be continuous, but was likely, if anything, to worsen. And when I went back to Israel in the summer of 2024 to check my historical facts and to, most of all, refresh my visual memory of everywhere I had been twice a day, every day, but 43 years ago. So I really needed to refurnish the visual details. I already had a group of Israeli friends and first readers who had already read the novel, and especially that last chapter, which is set in Jerusalem in April of ‘81. I didn’t want to go back until I’d finished the first draft of the novel and put the pages in their hands. And I remember that in the summer prior, the summer of 2023, they were saying, “Better come now. You may have trouble getting here next summer. There may be travel restrictions.”

Well, there were. And by the time I went to Jerusalem in July of 2024, it was already a war zone. The war in Gaza was ongoing. The troubles in the West Bank were escalating. The trouble from Lebanon was heating up. I remember feeling guilty that, well, yes, I had what I had foreseen, what seemed to be so clearly foreshadowed to me in 1981 was indeed true, but worse than I’d imagined. And I felt guilty that because of the war, my work, my job, retracing my steps through the old city, becoming familiar again with a trip I made to work with my Hebrew translator 43 years prior, retracing those steps until it became familiar to me all over again. Well, my work was easier because there were no tourists in Jerusalem in the summer of 2024. Tourists don’t go to a war zone. I was alone most evenings reading over my notes for the day, mapping out where I would go the next day. My Israeli friends were already at anti-Netanyahu protests. So that was my situation.

Sari Botton:

I can see now why you chose April 1981 as the ending point, but also the starting point for you in writing this book, which brings me to a really important question. So I know you’ve been outspoken about how you don’t like Hemingway’s dictum, “Write what you know.” I also, back in the ‘90s, I attended a talk, a conversation you had with Michael Ondaatje at the Ethical Culture Center in Manhattan where the subject was, “Should you write what you know?” And what I see you doing again and again is using autobiographical information as scaffolding and then-

John Irving:

Scaffolding is a good word. Yeah.

Sari Botton:

Building around it. So I wonder if you can talk a little bit about the difference. And also a word that we hear a lot now is autofiction, and I struggle to really understand what that means. To me, most autofiction to me reads like memoir that people are trying to have some plausible deniability for, but it’s a big movement now, but I would say you are not writing autofiction, but you are using-

John Irving:

Thank you. Thank you very much.

Sari Botton:

Okay. You’re using-

John Irving:

I certainly am not writing autofiction.

Sari Botton:

You are using autobiographical details as scaffolding and then building around it. And I wonder why-

John Irving:

Not just using, not just using, but changing the... Yes, I do use it. I was a student in Vienna in 1963 and ‘64, but those weren’t my roommates. I had a Jewish roommate who opened my eyes all the more to antisemitism in Vienna. My circumstances were different, but what I took away from Vienna was pretty much what Jimmy learns. I’ve said before that Jimmy Winslow, the point of view character, is another one of my writer characters who, yes, bears certain autobiographical resemblances to me with a couple of notable exceptions. His story, Queen Esther’s story, is much worse, more frightening, more terrifying than anything that ever happened to me. Nothing at all that interesting ever happened to me. But there were many starting circumstances, scaffolding, as you said, that I have used or borrowed. But it was always my intention that in Vienna in the ‘60s, in Jerusalem in 1981, I intended for Jimmy to be what I call a truthful exaggeration of me.

Sari Botton:

That’s a great term, truthful exaggeration.

John Irving:

He is even more unaware or more out of it than I was. I was out of it. I was unaware, but I wasn’t anywhere near as out of it as Jimmy is. And I had a lot more variety in my experiences, both in Vienna in the ‘60s and in Jerusalem in 1981 than I’ve allowed Jimmy to have. I’ve given Jimmy what the Germans call... He’s a [foreign language 00:23:30]. He’s a horse with blinders.

Sari Botton:

Ah, that makes him a really good point of view character.

John Irving:

If it weren’t for all the people who-

Sari Botton:

Yeah.

John Irving:

Yes.

Sari Botton:

Yeah. He is taking everything in as we are because he’s got such limited exposure and knowledge.

John Irving:

Exactly.

Sari Botton:

I heard you call him the point of view character. So would you say that this novel has two protagonists? Are Esther and Jimmy both protagonists or is one the protagonist and the other is representative of something else?

John Irving:

I’m a little indifferent or particular about the protagonist word and the main character definition. There’s another parallel that Queen Esther has in common with The Cider House Rules. Dr. Larch, in my opinion, I think in anyone’s opinion, is the main character of The Cider House Rules in the sense that he is the one who makes everything happen. Everything in the story happens because of who Larch is and what Larch does, including the character who’s on the page most of the time. For hundreds of pages, Larch isn’t there and you’re stuck with his unadoptable orphan, Homer. But Homer is doomed to go back to the orphanage. He is doomed to replace Dr. Larch when Dr. Larch dies. So that Larch, like a puppet master, is controlling what will happen to Homer.

And Homer’s coming back as he always did in all those years no one took him, when he was adopted and sent back, when he was adopted and cast out. Well, think of it this way. There are many pages when Esther herself is missing from Queen Esther. And we’re staggering around with Jimmy. And Jimmy’s mother by name, her efforts to keep him out of the war in Vietnam. And for all that time, when Jimmy is in Vienna and he has a Jewish German tutor, we are increasingly aware that Esther is pulling the strings. Esther is the puppet master, that Fräulein Eisler is in Vienna to be Jimmy’s tutor because of Esther. She’s calling the shots. Well, in this regard, she is the Dr. Larch of this novel.

But it was always my intention that my Esther be the embodiment of the Esther she is named for, the Queen Esther in the Hebrew Bible, in the Christian Old Testament, who I remember reading about in high school when I had a terrific course in the Bible as history or the Bible is not history. It’s very unlikely that there ever was a Jewish queen of Persia, which Esther in the Book of Esther is. But because there’s a Jewish queen of Persia, and boy, does she have to keep that in hiding, that’s the wonderful thing about this character. She’s like a character in a 19th century novel. She’s hidden, hidden, hidden. Her Jewishness is a secret until she comes out. And when she comes out, watch out.

Sari Botton:

Yep.

John Irving:

That’s the story. Well, and that was who I wanted my Esther to be. I wanted her to be, in her estimation, the best Jew she could be. And I front-loaded her deck. I gave her every reason as a child to have this agenda, every good reason. And so I was trying to reflect in her that model of hiddenness and then heroism, which the biblical Esther is a model of.

Sari Botton:

Yes. Yes. Okay. In this book, and as in others, you touched on asexuality and unique family structures. For instance, in this one, Jimmy Winslow has two moms. His birth mother is Esther Nacht, who we’ve been talking about, who’s the main character of the book. And Honor Winslow is the mother who raises him. And this is an arrangement that is very intentional from the beginning. And they find a Jewish progenitor, they find a Jewish man for her to become impregnated by. Then Jimmy himself enters into an unusual parenting arrangement, impregnating one of two lesbian friends who are partnered. Why are you drawn to creating these kinds of unusual family arrangements? I find them refreshing and interesting. It’s just, I’m curious about that.

John Irving:

Well, I can take credit for what I imagine and for I think the ending-driven pre-conceived construction of my novels, but I can’t take credit for creating my childhood and my early adolescence. I’m not a woman. I’ve never been pregnant, but The World According to Garp is, as it was called, both in praise and in condemnation, a feminist novel. I was introduced to abortion rights and abortion rights activism because of who my mother was. She was a nurse’s aide and her longstanding job was in a New Hampshire County counseling service where she spent most of her time counseling young unmarried women, some of them girls who were too young to be of legal age to have sex in New Hampshire. And this was both before Roe versus Wade and after it. So that my mother’s work made her angry. These young women and girls, she was trying to help, trying to counsel with their considerably unwanted pregnancies.

She brought her work home and then she talked about it. And so I was introduced to women’s rights and abortion rights before I was aware of abortion rights advocacy. I didn’t think it up. It was in my face. It was in my life. Well, my younger brother and sister were boy-girl twins who turned out to be gay and lesbian. I wasn’t very old before I realized I had to be afraid for them. I had to be worried about how other people were going to treat them. And so in other words, my being an ally to women’s rights and abortion rights, my being an ally to LGBTQ characters in my fiction, think of how many trans women in my novels are heroic trans women. Well, I came to that because of a family connection. Now you add to that, my growing up in a small New Hampshire town where I didn’t know any Black kids, there weren’t any Black kids in this small New Hampshire town.

And I knew very few Jewish kids. But at the age of 15, I went to an international boarding school where there were kids from all over the country, all over the world. And I was a part of a wrestling team. And the friendships I had among my wrestling teammates for 20 years, for 20 years, beginning when I was 15. The friendships you have with your wrestling teammates are a lot closer than other friendships. In much of that time, I had no friendships with people who wanted to be writers that were comparable to these teammate relations. And these, my wrestling teammates, these were the first Black kids and the first Jewish kids I knew. And I heard about what it was like to be a Black kid in St. Louis, what it was like to be a Jewish kid in Chicago. I heard their stories, and I heard how they were occasionally treated and beaten by people at the school for being Black or for being Jewish.

So I was aware of myself as an ally to these guys I knew and was close to, who’d had much more difficult lives than I had. So those identities were very much in my mind. And I mentioned the Jewish roommate I had when I was a student in Vienna, who opened my eyes to countless incidences of antisemitism that in many cases would’ve just gone over my head if I hadn’t been with him. And he was very much on my mind that first time I was in Israel with my Jewish European publishers. He wasn’t with me, but I thought of him. I knew he’d been to Israel. I wished he’d been there. And when I was back in Israel in the summer of 2024, by which time he had died, he was not only on my mind, but I was very much saddened by the awareness that this would be the first of my books that he would never get to read because he had always been.

We’d been very close as roommates in Vienna. He read everything I read. He’d read everything I wrote in manuscript before it was published and always did. And it was very much on my mind that, “Ah, Eric is not going to get to read this one.”

Sari Botton:

I’m so sorry.

John Irving:

It was always in my mind that this was the one he might’ve liked the best.

Sari Botton:

So you’re bringing me to a question. So I’m going to do some questions from my Oldster readers. This question dovetails with what you’ve just been talking about. It’s from Lauren Sanders. “Garp rocked my 15-year-old world.” Mine too, by the way. I was so excited to also be reading a dirty book... “Part of what made me think it was okay to be different, to be a writer, feminist, weird. It is such a beautifully queer book. What do you make of how popular it was? And do you think only a cis white dude, a very cool one at that, could have made this book a bestseller then in the early 80s? Does your position as someone straight and white and male, did that, especially prior to now, did it give you an advantage in terms of your ability to tell these stories that marginalized people maybe couldn’t have told at the time?”

John Irving:

Well, you have to remember that The World According to Garp was my fourth novel. And by then, I was a newcomer to having a bestseller. I was a newcomer to having suddenly many translations. That was new to me, but I think it was all a positive experience for me because for the writing of those first four novels, I was lucky if I got to write for two hours a day and not every day. And I had two young children, and I was always working as a wrestling coach and an English teacher and thought I always would be. So the success of Garp, to speak of horse with blinders on, meant only one thing to me. It meant that I could stop the teaching.

Sari Botton:

And become a full-time writer. Yeah.

John Irving:

And I could write all day for seven days a week, and a sudden luxury was about to be afforded to me. I don’t regard the writing of a novel as necessarily a sociological event. And the sociological part of the question, my being a straight white writer, making my feminist politics of the time more accessible. I can’t answer that question. I had a good editor, a good publisher for my first three novels, who was so good that he recognized that as much as he was behind me as an editor and a publisher, he was not able at the time to persuade his fellow editors at the publishing house to support me as he thought I should be supported. And he purposely, when he read only the first few chapters of The World According to Garp, he said, “I’m going to do you a favor. I’m going to pretend to turn this novel down so that you can take it to another publisher where you might have a hope of getting the whole support of the whole publishing company behind you, which I have been unable to do here,” was the most generous thing he did.

And he didn’t just say that. He told me who to take it to. And it was good advice again. And later after Garp, when that new editor he had found for me died, and I turned back to him and said, “Well, Henry’s gone. Should I come back to you?” And he said, “Not yet. Not until everybody here is begging me to have you come back, and they’re not begging yet.” And he told me who else to go to. And he told me who else to go to. And when things started to go south at that house, he said, “Okay, now come back.”

Sari Botton:

I love that story.

John Irving:

So I had a guardian angel, and I think that’s why everything worked. This guardian angel who had been loyal to me and a great editor to me and a great backer to me for my first three novels had the presence of mind to say, “I’m not succeeding with you here.” He didn’t say, “You’re not succeeding.” He said, “I can’t get through to the people here. I’m going to send you to somebody else where you might have a better chance to get a whole house behind you.” And he was right. He was right twice. He did it again.

Sari Botton:

This next question-

John Irving:

So that’s my perspective. The second part of the question is just, it’s impossible for me to go back and have that much hindsight, but it was nothing I was ever thinking of or nothing I was ever aware of.

Sari Botton:

Got it. Okay. This next question comes from both my mother, Francine Fleishman and my aunt, BARBARA MASKET. They want to know if you knew a character like Owen Meany because they both love that character so much and they wonder if he was drawn from life.

John Irving:

Well, drawn from life isn’t accurate. I draw from my own life, but I feel I have the liberty to change it. In other words, I take from my own life the few things that are interesting, and then I make my character’s lives much more interesting than my life ever was, or much more dangerous or threatening, or much unhappier, or much more unhappy than my life ever was. Well, Owen Meany was born as a character. Actually, accidentally, one night when I was back in my hometown, my birth town in New Hampshire, and it was Christmastime. I was married. I had a couple of children. I was just staying with my parents, and I reconnected with some childhood friends. Yes, you could say some of them were prep school friends, but many of them were even before I started the prep school, they were childhood friends.

And Christmas was a time when people who no longer lived in Exeter, New Hampshire came home to see their parents. And so you could reconnect with people that you had known for a long time, but maybe not known very closely in recent years. And the conversation, as for people my generation, often their conversation evolved this way. We began to remember the friends we’d lost in the Vietnam War, either in the war, because of the war, or because of what measures they took to evade the draft, which cost them their lives in other ways. And so it was a morbid thing that I remember for a few Christmases was common because that war was something that affected every one of my age and generation. Every young man I was a coincident in age with and everyone... We all knew each other’s. We all knew one another’s Vietnam stories.

And we always had this moment of morbidity when we remember the guys whose lives were lost, either in it or because of it, both ways. And someone mentioned a boy I barely knew. I do remember him in Sunday school, but then our ways parted. He never went to the boarding school with me. So I remembered him at an earlier age only. And he was so small. At whatever age we were in Sunday school, there was something that I included in Owen Meany. He was small enough so that everyone was attracted to picking him up, which was so easy to do, and he hated it. And we picked him up because he would always say, “Put me down, put me down.” And we did it because he had this little squeaky voice that was as funny as he was. And we did it. We picked him up to hear him protest being picked up.

But he was our age, but he was just diminutive. And someone mentioned his name as someone who died in Vietnam. And I said something that was categorically stupid. I hadn’t seen this kid since. I mean, he was still growing the last time I saw him. He wasn’t a teenager. He was six or seven or seven or eight or something like that. But he was so much smaller than the rest of us. Everybody picked him up. The girls picked him up. Everyone picked him up. And someone mentioned this guy’s name, and the name didn’t ring a bell. I couldn’t remember his name. And I said, “Oh, I don’t know him.” Which meant to say, “I didn’t remember his name and I don’t remember it now.” And I said, “I don’t remember him.” And one of my friends said, “What do you mean you don’t remember him?” “You used to pick him up in Sunday school.”

And well, I remember that kid and I said something that was so stupid. I said, “He died in Vietnam.” And I instantly thought and said, “How could he have gone to Vietnam? He was too small.” And everyone just groaned. And someone looked at me and said, “Johnny, he probably grew.” And I went home and I was up all night thinking, “But what if he didn’t grow?” And it all came from that moment when I couldn’t even remember this kid’s name and I asked this stupid question and someone said, “Duh, he probably grew.” But I had it in my mind, I kept seeing this kid. I had it in my mind and said, “Yeah, but what if he didn’t?” And it went from there.

Sari Botton:

You have a lot of small men. There are a lot of characters who are small men, even in this book.

John Irving:

I’m a small man.

Sari Botton:

And it’s funny, I’m remembering now that I had a boyfriend, I call him my 9/11 boyfriend because I met him at a vigil for 9/11, and he was from New Hampshire and small. He was 5’ 3”, and we had nothing in common. He was an athlete. I failed gym in ninth grade. And to try and have something to be involved in together, we read The 158-Pound Marriage, both of us, and then talked about it. And I loved that book. And it’s also a short book.

John Irving:

Yes, it Is.

Sari Botton:

A novella. But yeah, there’s a lot of short men in your novels. Okay. Next question is from Jennifer Covell. “Will you be revisiting characters of any other books in future ones?” I know you’re working on your 17th book. I’ve read a few interviews with you.

John Irving:

You know, it was never a plan. I never thought consciously of revisiting a character from a previous book. I knew, as I said at the beginning, I knew because of Esther’s storyline that I needed an orphanage, and I knew what time in history she would’ve been in.

Sari Botton:

You had an orphanage.

John Irving:

I thought, I know an orphanage. I know a physician. Okay, he’ll be younger. So what? It was great that he would be younger because I wanted the cast of characters among the unadoptable orphans to be a completely different cast of characters, and they would’ve been. But the timeline and who Esther became as an adult was where I began. And working my way backward, I thought, “Aha, send him to St. Cloud.”

Sari Botton:

Love it.

John Irving:

And so the answer is no. I have no desire to return to fictional characters from earlier novels. But in this case, strictly because of Esther’s story and what her trajectory is, it was a no-brainer. I thought, of course.

Sari Botton:

That’s a good setup for my next question, which comes from Katie Mather. “Do you have any written outlines of your novels? And if so, can we see one?” Because you’re talking really about plotting, starting at the end, going back to the beginning. Do you outline? And if so, do you have any outlines and can you share one with us?

John Irving:

Well, I suppose there are in my notes for earlier novels. I suppose there are things that resemble outlines or strategies. I don’t think of them as outlines so much as timelines. And I definitely have cast of characters when they were born, when they die, if they die, if they live, why they live. I don’t make maps, but I can’t share one with you because you can see a little bit behind me some piles of pages there. Those are things waiting. And now because of laptops and so forth, there are other means of hoarding things. But no, I can’t share one. My archives, my first drafts, all of those pages are at the Lilly Library at the University of Indiana in Bloomington. So if someone were really interested in seeing the notes I take prior to beginning a novel, I suppose you could view them there, but I don’t know how to share.

Sari Botton:

It was too much to ask, but I’ve just asked about that.

John Irving:

I have. I don’t call it outlines. I mean, cast of characters, timeline, storyline, always crafted from back to front, from end to beginning. I come to beginnings last.

Sari Botton:

Okay. So here’s my last question. This is from me. So you’ve answered the Oldster questionnaire and you did it defiantly, which made me laugh. You say you don’t think about age, that it’s a non-subject for you. I have been obsessed with what it means to get older since I was 10 years old. It’s my obsession, which is why this magazine exists. So I wonder why you don’t see it, age as your ages and different points of life as an important set of coordinates the way that I do.

John Irving:

Well, I feel that I’ve been lucky in terms of my health. The things that have gone wrong were diagnosed quickly and addressed in an appropriate manner. I’ve had good habits in part because of my athletic background, my training as a wrestler. My mother was a nurse’s aide who made me very conscious of being healthy to the degree that you can be in control of those things. But as I said in the questionnaire, I don’t find it constructive to dwell or ponder one’s age. Because it’s one of the things that you can do nothing about. I mean, the things you should be addressing, the things that should preoccupy your thoughts are the things you can do about something, the things you can change about something. And you can’t do anything about how old you are.

To me, there’s a comparable or a parallel obsession now with one’s ancestry. People have become fixated on their ancestors. Well, there’s some early advice in Queen Esther from Thomas Winslow, who questions having anything to do with thinking about one’s ancestors. For the same reason I don’t think about age. You can’t change your ancestors. There’s nothing you can do about your ancestors. You can’t hide them or deny them. And if you’re dwelling on them, it does amount to a kind of self-pity. There’s no forward direction there. To me, it’s like I was involved for 20 years in a sport where there are injuries and sometimes one of those injuries will take away your wrestling season or longer. And there’s a requisite surgery and there’s a requisite recovery. But all you can do is go forward. And ancestry is dwelling on it. To me, it’s a strange obsession.

And I feel it’s never been particularly useful to me or for me to think about my age. I think much more about what’s going to happen to my characters in a novel. I have to know what happens to my characters. Before I begin a novel, I have to know how they all end up. But it’s a waste of time to wonder about where I end up. Ideally, I’d like my head to be right here. I’d like to conk out at my desk. It would be the easiest thing for my wife and children. I would be properly dressed. They would know where to find me. They would at least know where to look for me when I didn’t show up for dinner. Fine. I’d like to be in the process of doing it. I hope that I don’t have something that incapacitates me to the degree that I can’t continue to write because it’s hard for me to imagine wanting to be alive if I can’t continue to write.

But that thought is worth less time than it took me to say it because whatever that is, I can’t change it. You can do something about your habits. You can do something about your diet. You can do something about your exercise or the lack thereof, but you can’t arrange the future. There’s a moment, I’m going to take us back to Queen Esther. There’s a moment in the Vienna chapters where the little boy who is growing up in this considerably angry and dysfunctional family overhears one of Jimmy’s roommates say something, which is a mistranslation. The roommate is trying to explain to Siegfried what a telescope does.

And he means to say it sees into the distance. It looks into the distance. But instead of using the word distance, he says future. And he says it looks into the future and he invites Siegfried to look into the telescope to look into the future. And Siegfried is terrified of the prospect of looking into the future. He’s frightened and he runs away from the telescope. And Jimmy feels really badly that his roommate frightened this kid. And so he says later to the boy’s mother, he’s still worrying about this trauma to Siegfried, the telescope that looks into the future. The mother is not so worried. She’s a tough character. And she says to Jimmy, “There is a telescope that sees into the future, Jimmy. It’s called the passage of time.” And okay, what I have to know as a writer is the passage of time. It’s a waste of time to contemplate my own passage of time. That’s not teaching me anything.

Sari Botton:

Well, that’s a great place to end. Thank you so much, John Irving. I am so honored to interview you.

John Irving:

Thank you, Sari. Thank you.

Sari Botton:

Will you do me a favor and hold up the book again? I don’t have the book with me because-

John Irving:

Absolutely.

Sari Botton:

I’m taking care of my mom this week on Long Island. Yes.

John Irving:

Absolutely.

Sari Botton:

Everybody, go get Queen Esther and enjoy it. And thank you, John. It’s been so wonderful to talk with you and thank you for taking the Oldster questionnaire. Thank you for being such a good sport.

John Irving:

You’re welcome. You’re welcome. Thank you. Thank you very much.