Letter from the Editor #19

Fast or slow: what's the best way to die?; The world's most boyish glaucoma patient turns 64 (I'll still need him and feed him)...

Readers,

Whether you’re attached or not, or even single by choice, I hope you had a nice Valentine’s Day.

In case you missed it, I’m running a Valentine’s Week special on paid subscriptions that ends Saturday: 25% off annual subscriptions for life.

Big thanks to those who are already paid subscribers. I very much appreciate your support. 🙏

Check out the rest of this series here. P.S. Typos happen. Please forgive me if you find any!

Fast or Slow: What’s the Best Way to Die?

Sorry if that sub-headline sounds blunt. But we don’t talk enough about death and dying, and I want to foster more frank conversations about those topic here at Oldster.

I’ve already had some posts on end-of-life plans and writing our own eulogies, and communities of care for our final days, and living with grief. Next month I’ll have a piece that touches on the Death With Dignity movement. Now this is on my mind.

***

I’ve been chatting with my mother lately about an 86-year-old friend of hers, her best friend since 5th grade, who’s “dwindling” at the end of life—lingering for years on end with advanced dementia, some paralysis from a stroke, and recurring cancer. We’ve discussed again and again how cruel this long, drawn-out ending it is for my mother’s friend, her family, and friends.

But the truth is, a sudden ending can be just as cruel. Take my husband’s childhood friend who a couple of years ago died suddenly at 55 from a massive coronary, leaving everyone around him stunned. He was driving home from a gig with his band when it happened, and he had the fortunate presence of mind to pull over to the side of the highway before fully succumbing.

Ironically, at the moment Brian looked up from reading about his friend’s death on his laptop, I was in the middle of reading “My Father’s Body at Rest and in Motion,” Siddhartha Mukherjee’s excellent scientific personal essay in the January 1, 2018 issue of New Yorker about his octogenarian father’s excruciatingly slow demise after suffering a few falls. Sometimes death takes a torturously slow, scenic route.

Mukherjee, a physician, considers the body’s proclivity toward homeostasis, which kept his elderly father’s failing body alive for months—much longer than seemed to make sense. He writes:

“Old age is a massacre,” Philip Roth wrote. For my father, though, it was more a maceration—a steady softening of fibrous resistance. He was not so much felled by death as downsized by it. The blood electrolytes that had seemed momentarily steady in the I.C.U. never really stabilized. In the geriatric ward of the new hospital, they tetherballed around their normal values, approaching and overshooting their limits cyclically. He was back to swirling his head vacantly most of the time. And soon all his physiological systems entered into cascading failure, coming undone in such rapid succession that you could imagine them pinging as they broke, like so many rubber bands. Ping: renal failure. Ping: severe arrhythmia. Ping: pneumonia and respiratory failure. Urinary-tract infection, sepsis, heart failure. Ping, ping, ping.

Those feats of resilience surrendered to the fact of fragility. And, as the weeks bore on, an essential truth that I sought not to acknowledge became evident: the more I saw my father at the hospital, the worse I felt. Was he feeling any of this? Two months had elapsed since his admission to the geriatric ward.

I read Mukherjee’s piece on the heels of revisiting “A Life Worth Ending,” a similar 2012 New York Magazine piece by Michael Wolff1, about his mother’s dwindling in a miserable, expensive, endless-seeming purgatory in the year before her death.

Wolff—who includes the exact same Philip Roth quote in his piece—writes of his frustration witnessing his mother’s last years, when she seemed caught precariously and unenviably between life and death; not well enough to live on her own without tremendous intervention from her family and doctors, but not sick enough to quickly die. He makes a convincing case against the medical establishment’s endeavors to keep the dying alive long past such time as they are able to thrive on their own, leading to painful, slow deaths that deplete families and taxpayers.

Age is one of the great modern adventures, a technological marvel—we’re given several more youthful-ish decades if we take care of ourselves. Almost nobody, at least openly, sees this for its ultimate, dismaying, unintended consequence: By promoting longevity and technologically inhibiting death, we have created a new biological status held by an ever-growing part of the nation, a no-exit state that persists longer and longer, one that is nearly as remote from life as death, but which, unlike death, requires vast service, indentured servitude really, and resources.

This is not anomalous; this is the norm.

The traditional exits, of a sudden heart attack, of dying in one’s sleep, of unreasonably dropping dead in the street, of even a terminal illness, are now exotic ways of going. The longer you live the longer it will take to die. The better you have lived the worse you may die. The healthier you are—through careful diet, diligent exercise, and attentive medical scrutiny—the harder it is to die. Part of the advance in life expectancy is that we have technologically inhibited the ultimate event. We have fought natural causes to almost a draw. If you eliminate smokers, drinkers, other substance abusers, the obese, and the fatally ill, you are left with a rapidly growing demographic segment peculiarly resistant to death’s appointment—though far, far, far from healthy.

***

A few nights after his childhood friend died suddenly, my husband attended the funeral. When he came home, we got into a discussion about how strange it is that for the most part, none of us have any idea how or when we’ll exit this plane, and no control over the matter. We debated whether those faster “traditional exits” Wolff identifies are better or worse than slower routes, which afford loved ones time to prepare and say goodbye.

We ended the evening as mystified as we’d begun it. The only conclusion we could arrive at was that the Grim Reaper is fickle, inconsistent, and unpredictable.

***

Relatedly, I had an interesting phone conversation recently with Eve France. She wanted to know if I knew about death cafes—gatherings where people have tea and cake and talk about various aspects of death and dying. I’ve heard of these, and know some people who take part in one here in Kingston.

In the spring or summer, I’d like to publish a post on death cafes. If you run one, or know someone who does, or you take part in one, leave a comment and I’ll follow up.

And if you have thoughts on my fast-or-slow question, leave a comment about that, too.

The world’s most boyish glaucoma patient turns 64. (I’ll still need him and feed him)...

Happy 64th birthday to my favorite person, my husband, Brian Macaluso! He was 41 when I met him, and he still seems so young to me. I offered him The Oldster Magazine Questionnaire, but he wants to wait until 65.

I did get him to share a little bit about what it’s like to be his age. Here’s what he had to say:

I feel pretty youthful, generally! But I am definitely noticing that I don’t heal as quickly from injury. Like my bicep still hurts three weeks after straining it while shoveling snow. That’s frustrating. Also, I realize I need to get my hearing checked. I’m feeling those decades of being in loud bands…

Here, have a Beatles song:

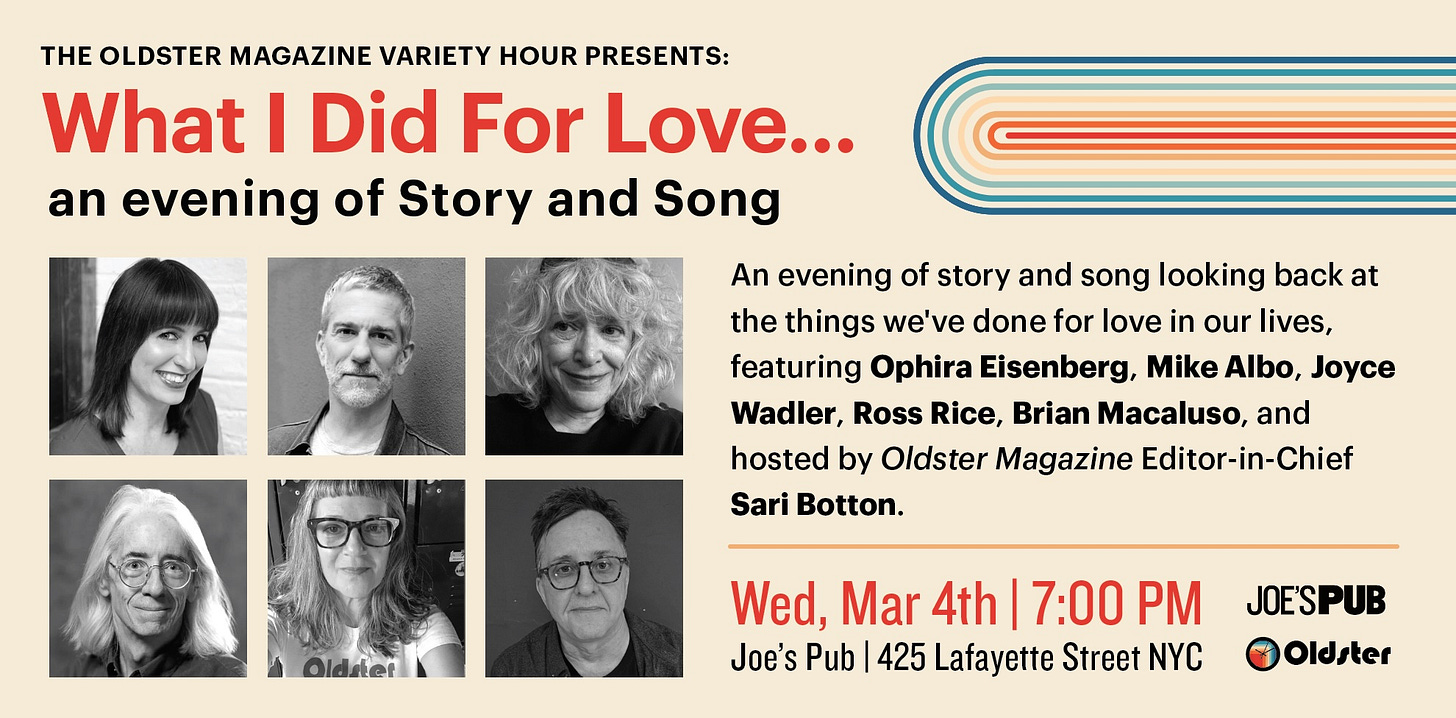

Just two weeks until the Oldster Variety Hour at Joe’s Pub…

Have you gotten tickets for the March 4th Oldster Variety Hour at Joe’s Pub? If you want to attend, don’t sleep on grabbing your seats! It’s going to be so great, and it’s almost sold out.

If you do get shut out—or if you don’t live in or near New York City—I’ve got good news for you: I’ve found a way to make remote live streaming available. Remote streaming tickets are just $10. (And they’ve been selling! Thank you.) You can watch from anywhere, live, or on your own time for up to a week after the show.

No paywall this week…

This week I’m not putting the bottom part of my Letter from the Editor behind a paywall, as I had in prior installments. Sometimes it takes a paywall to inspire readers to support your work, but I don’t like to exclude people. If you enjoy all that I publish here, I’d love your support. Publishing Oldster takes a lot of work. 🙏

Check out the rest of this series here. P.S. Typos happen. Please forgive me if you find any!

That’s all for today. Thanks for reading, and subscribing. I appreciate it. 🙏💝

Inspired by Claire Dederer, I’m doing my best to separate the art from the artist. And that essay is really good.

Fast or slow, as humans most of us resist the fact that we are going to die, that our loved ones are going to die, that humans die. All of us. Although a slow death is sometimes not dramatic and painful, as you wrote, often it is painful to *witness* and despite the comfort of holding a vigil at a bedside, being present and involved and caring, my experience is that the declaration/appearance of the instance of death is almost always a surprise and a new shock to the system. Despite all the preparations, and sitting, and watching. Sudden death, the helplessness of that, for which there is no real preparation, comes built-in with the shock of death to the living. The only antidote I know for finding some sort of peace with both a fast death or a slow lingering death is to openly, as best as one can considering how difficult some human relationships can be, love and love and love all the time and with the greatest generosity possible.

After observing the deaths of people across a few generations, I’d choose a fast death. Get your plans and paper work in order, tell the people you love how you feel, pass on anything important while you can share the reason it matters to you. My husband and I tell each other periodically, “Don’t save me.”