This is 56: Author and Writing Instructor Jeannine Ouellette Responds to The Oldster Magazine Questionnaire

"Aging has allowed me to see and claim the power of my own survival."

From the time I was 10, I’ve been obsessed with what it means to grow older. I’m curious about what it means to others, of all ages, and so I invite them to take “The Oldster Magazine Questionnaire.”

Here, author responds. -Sari Botton

P.S. A reminder that in my book, everyone who is alive and aging is considered an Oldster, and that every contributor to this magazine is the oldest they have ever been, which is interesting new territory for them—and interesting to me, the 58-year-old who publishes this. Oldster is an ongoing study of the experience of aging at every phase of life.

When you see a piece featuring someone younger than you, try to remember when you were that age and how monumental it felt. Bring some curiosity to reading about how the person being featured is experiencing that age. Or, if you prefer, wait for the next piece featuring someone in your age group. Not every piece will speak to every reader. I’m doing my best to cover a lot of ground and to foster intergenerational conversation. Please work with me.

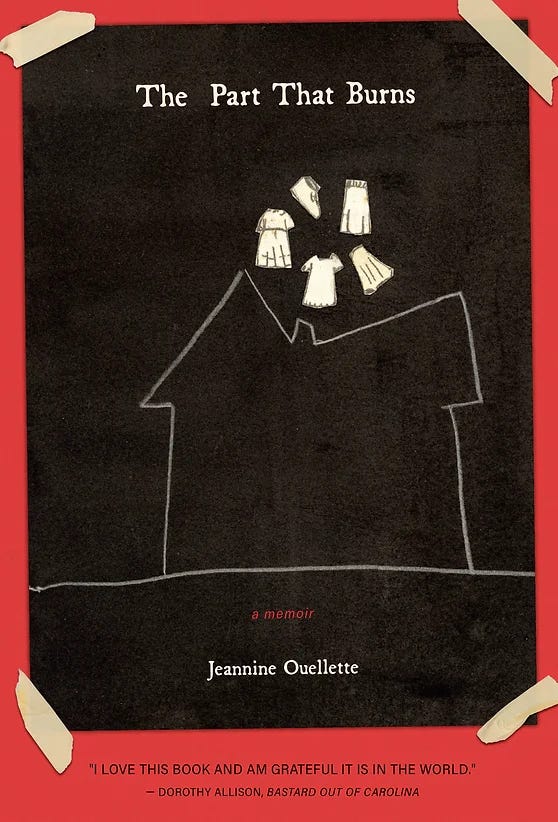

Jeannine Ouellette’s memoir, The Part That Burns, was 2021 Kirkus Best 100 Indie Book and a finalist for the Next Gen Indie Book Award, with starred reviews from Kirkus and Publishers Weekly. Her award-winning essays and fiction appear widely in literary journals including Los Angeles Review of Books, Narrative, Masters Review, North American Review, Calyx, and more. She teaches writing at the University of Minnesota and through the Minnesota Prison Writing Workshop as well as through Writing in the Dark, a creative writing program she founded in 2012 that now includes her Writing in the Dark community on Substack. Jeannine is working on a novel.

--

How old are you?

56

Is there another age you associate with yourself in your mind? If so, what is it? And why, do you think?

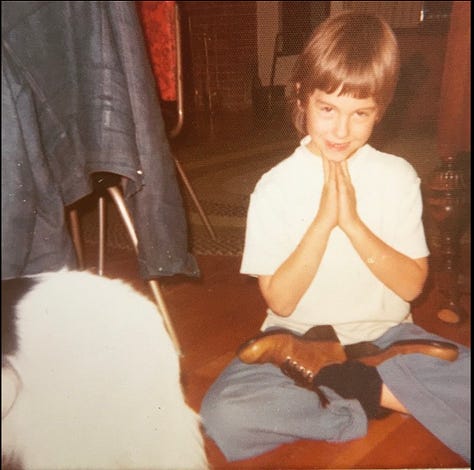

I see myself as a 9-year-old—a feisty one. I started out in life as a tiny thing who made up for my smallness with my energy and courage and fierce stubbornness. I was going up and down slides alone at 1! My mother called me a “little beast.” But by adolescence, I had outwardly withered, I became pathologically shy. You know, abusive home life, chronic moving, all that stuff—I went to something like twelve different schools. And I lost my footing.

But at 9, I still felt my own limitlessness.

Also, at 9 I had a group of close friends, something I never had again until very recently. There were five of us girls, blazing with creativity. We were unstoppable. Every day we’d practice the penny drop, where you swing upside down by your knees on the monkey bars, then flip off onto your feet. I was superb at it, never afraid. At my friend Norah’s, we’d leap from a second-story porch roof onto a trampoline, launching each other a dozen feet into thin air toward the distant mountain. We could have died, but we never thought about it. Norah’s attorney father required our parents to sign releases.

On weekends we’d walk many miles across fields of cactus and sagebrush to climb Casper Mountain until we were dizzy with thirst. We’d write poems while splayed out on Norah’s widow’s walk high above the city—wild, alive poems that sprang from the hugeness of our imaginations. We were hungry for those poems, and for everything else, too. We could never fill ourselves. We’d sneak into the teachers’ lounge at school and steal whole pans of brownies and Rice Krispie bars, swallow them down and hide the empty pans.

That girl, that boundlessly hungry 9-year-old, is the part of me that feels most real.

In high school, when my family came apart at the seams for good, I spent time living with teachers and friends before I finally landed in foster care—and it’s simply impossible to feel in step with peers when you’re in these situations. The way I solved for that was by rushing into marriage as fast as I could then having a baby literally ten months after the wedding. I was 22, four years out of foster care when my daughter was born, and what I thought then was, I did it, I made it, I can be like everyone else now.

Do you feel old for your age? Young for your age? Just right? Are you in step with your peers?

Until my late 40s, I felt much older and much younger than my peers.

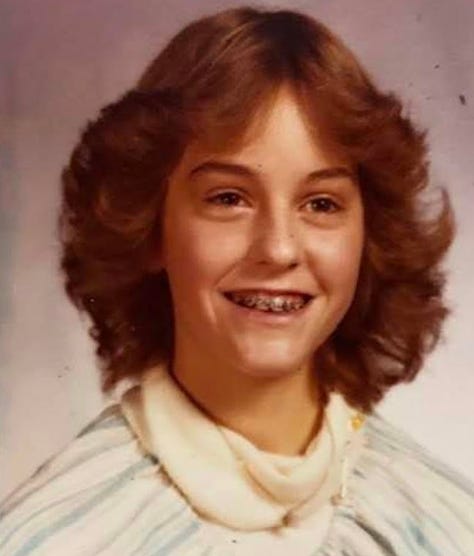

The older part started in childhood, when I felt ages older than my friends, like I could be their mother—by age 6, I was washing my baby sister’s diapers and getting up in the night with her. By 9, I was babysitting her alone and soon after, I was walking her to kindergarten and back. By 10, I was ironing my mother’s boyfriends’ shirts for a quarter each on Saturdays.

Then when my mom sent me to live with my dad at the end of sixth grade, I went from this sleepy small-town elementary school in Wyoming to a huge suburban junior high full of Jordache jeans and Nike tennis shoes and Farah Fawcett hair, kids making out between the lockers and stealing vodka from their parents’ liquor cabinets. I felt like a baby next to these kids, while also feeling one hundred thousand years older than them.

It was profoundly confusing.

In high school, when my family came apart at the seams for good, I spent time living with teachers and friends before I finally landed in foster care—and it’s simply impossible to feel in step with peers when you’re in these situations. The way I solved for that was by rushing into marriage as fast as I could then having a baby literally ten months after the wedding. I was 22, four years out of foster care when my daughter was born, and what I thought then was, I did it, I made it, I can be like everyone else now.

But unsurprisingly being such a young mom prolonged that sense of being too young and too old, of being separate—a sensation Bessel van der Kolk writes about so beautifully, this feeling of separateness among the traumatized. It took me so long to stop feeling that way. Motherhood did help, eventually, even though at first it was terribly lonely. Getting divorced helped. Getting remarried helped. Yoga and meditation helped. Friends helped. Therapy helped. Nature helped. Writing my memoir The Part That Burns helped hugely, and writing and teaching through Writing in the Dark keeps helping. Ultimately, writing has helped more than anything else, but I could not have written without this whole other constellation of experiences working synergistically to unify me with myself.

What do you like about being your age?

I love finally having real friends again—a luxury I haven’t enjoyed since childhood. Most of my closest friends are writers, and many of those friendships actually started in my Writing in the Dark workshop. Bringing Writing in the Dark to Substack has become a beautiful extension of that community. Thankfully, some of my friends live near me, but many are spread across the country and world, so we can’t all easily hang out like in childhood. Maybe we’ll start renting a big house on a lake or in the mountains or the desert in the not-too-distant future. It’s not that hard.

I also like the part of aging that has allowed me to say “fuck you” to perfectionism. I’m so grateful to be free of feeling like I have to fit some perfect external mold or else the whole world will see me as a monster. My mom used to threaten to call my teachers and tell them the truth about me—what I was really like at home, she said—the implication being that my teachers wouldn’t love me anymore because of some minor infraction like not doing the dishes fast enough or leaving a towel on the floor. But I was just a kid. I had a right to make mistakes and be imperfect.

I still do.

What is difficult about being your age?

The limitations of the human body. I have scoliosis and it hurts. I love Ada Limon’s poems on this topic.

Facing the clock of mortality is hard, too. Realistically, at age 56, a person can hope for 30, maybe 35 good and physically robust years ahead? That’s long, but also short.

I don’t want to waste it.

I also like the part of aging that has allowed me to say “fuck you” to perfectionism. I’m so grateful to be free of feeling like I have to fit some perfect external mold or else the whole world will see me as a monster. My mom used to threaten to call my teachers and tell them the truth about me—what I was really like at home, she said—the implication being that my teachers wouldn’t love me anymore because of some minor infraction like not doing the dishes fast enough or leaving a towel on the floor. But I was just a kid. I had a right to make mistakes and be imperfect.

What is surprising about being your age, or different from what you expected, based on what you were told?

Everything about aging has been a little surprising, due to lack of exposure. I had only one living grandparent, Nana, my paternal grandmother, who died at age 89 when I was only 25—and I didn’t live in the same city with Nana, so we didn’t have the kind of physical intimacy that allows you to see aging up close.

So, basically, all I had to go on when it came to ideas about getting old were stuff I picked up from the ageism and misogyny of the culture at large.

That started changing for me at least fifteen years ago when I did some freelance writing for Dan Beuttner, who studies Blue Zones—places around the world where people live the longest, healthiest, happiest lives. Dan introduced me to Bob Kane, who directed the Center on Aging at the University of Minnesota, and Bob hired me to co-write a book on caring for aging parents. After The Good Caregiver was published by Putnam, Bob offered me a writer/editor job at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health, where I still work. And for several years leading up to Bob’s sudden death in 2017, he had me writing profiles about extraordinary older individuals for a newsletter he called Old News, which was a little like Oldster, since it was inspired by Bob’s personal interest in aging. He wanted to understand how accomplished people like himself, mostly scholars and researchers and academics, found meaning and purpose in their lives post retirement, a threshold he absolutely dreaded.

I ended up writing a few dozen oral histories of truly fascinating people in their 80s and 90s and even 100s. I got to meet the diplomat Geri Joseph and the famous epidemiologist Henry Blackburn and the child welfare pioneer Esther Wattenburg, among many other fascinating scholars. In talking to these people, I saw the recurring themes and decisions that shaped their lives. And this sounds cliché, but they were all purpose-driven from start to finish. They contributed significantly toward the betterment of the world as they aged, in spite of physical limitations and health problems. One subject had severe MS, Geri Joseph had functional blindness, Bob himself dealt with a disabling chronic disease, etc. But still, these people were launching media companies, running for office, writing books, learning languages, staying connected to friends, adult children, grandchildren. A lot of them worked till they died, too, because they loved their work. Bob was in the office on Friday and died the following Monday, right after completing the New York Times crossword puzzle.

I want to be like Bob.

What has aging given you? Taken away from you?

Aging gave me back to myself.

Aging made me able to be playful and to laugh—just in time to share that with our five grandchildren. I’m a silly Nana! I wish I could have been like this with my own kids, but I wasn’t healed enough. Laughing requires letting go, and letting go requires some inward sturdiness. Besides, I was too determined to be a perfect mother, too afraid of making mistakes. Aging restored my playfulness.

Aging also brought me sexual pleasure. I was practically a virgin at 32 when I met my current husband. Yes, I’d had a handful of sexual partners—I’d been married already and had three kids. But I hadn’t experienced real sexual pleasure. Part of it was the men I was with, yes, but it was also just that I hadn’t been ready for pleasure. I was too estranged from myself to do anything other than endure what I thought was expected of me sexually. So, aging gave me the chance to be a sexual person. Hopefully what I missed in sexual quantity and variety in my youth—which was stolen from me by my stepfather—I’m making up for in quality now. My husband is a wonderful lover as well as a healer. He gets me.

As for what aging has taken away? Well, it’s taken away most of my crippling social anxiety and self-doubt, and almost all the shame for things that were never mine anyway.

I’ve lost some things I’d like back, though, like my smooth skin, fast metabolism, pain-free joints, and the ability to stay up past midnight. But it’s okay. I think it’s all okay.

I was practically a virgin at 32 when I met my current husband. Yes, I’d had a handful of sexual partners—I’d been married already and had three kids. But I hadn’t experienced real sexual pleasure. Part of it was the men I was with, yes, but it was also just that I hadn’t been ready for pleasure. I was too estranged from myself to do anything other than endure what I thought was expected of me sexually.

How has getting older affected your sense of yourself, or your identity?

Aging has helped me integrate my many selves.

But aging alone didn’t do that. Writing restored me to myself, especially when I finally started writing about my childhood. Neither of my parents speak to me as a result of my book, which isn’t great. But writing my story reunited me with myself. And to whom does the self belong, if not the self?

I should also say that writing about my childhood changed the whole trajectory of my writing career. I started making the best work of my life, work that drew praise from women I revere, like Dorothy Allison, Melissa Febos, and Lidia Yuknavitch. Without learning to write my childhood, I wouldn’t be the teacher I am, either. All the best things in my writing life manifested from writing my hardest story, despite the cost.

Aging has allowed me to see and claim the power of my own survival.

What are some age-related milestones you are looking forward to? Or ones you “missed,” and might try to reach later, off-schedule, according to our culture and its expectations?

I’m excited to retire from the University in ten years—I’ll have a pension! How amazing is that? My husband and I were both really broke in our younger years, working in low-paying jobs and running up credit card debt just to support our large family. But through a series of serendipitous events, we both ended up in jobs with pensions, which is pretty fucking amazing for two people who’ve always struggled financially. I mean, we got late starts and our pensions aren’t big, but the idea we’ll be able to support ourselves even spartanly without working day jobs till we die is still shocking to me. Maybe we’ll travel and have adventures. I’ll have more time to write books. Who knows what else might be possible!

What has been your favorite age so far, and why? Would you go back to this age if you could?

I like the age I am. I love my life. It’s not perfect—I endure some real entrenched difficulties and heartbreaking conflicts. I’ve lost some things I may never get back. But I still love my life. I think that’s what happens when you start to genuinely accept yourself. It gets easier to practice the advice in Ellen Bass’s poem, “The Thing Is,” where she tells us we have “to love life, to love it even when you have no stomach for it.”

That’s easier now.

Is there someone who is older than you, who makes growing older inspiring to you? Who is your aging idol and why?

I’ll tell you about Sally, who took my Writing in the Dark workshop on Zoom during lockdown. Many writers in that workshop were either published or had been taking classes for years, but not Sally. She had a story, though, about backpacking the globe with her husband Peter, something they started doing in the 1970s and never stopped. In fact, they just recently got back from a multi-country bike trip through Europe. Sally’s book—she’s starting to look for a publisher now—is kind of a love story framed inside a groovy ’70s travel wrapper—but she had just barely started writing it in that first workshop with me. And she would sometimes say, Wow, I have no idea what you are talking about, but I love this class and am going to keep coming! And it was incredibly refreshing, how curious she was and unselfconscious about being a beginner.

Then after a year or two on Zoom, Sally attended my writing retreat in Troncones, Mexico, and I got to meet her in person, and I was instantly smitten. She talked our whole group into joining her in “ocean aerobics” and I’m not kidding when I say that Sally—almost 80 then—had the best swimsuit on the beach. She travels with a battery-operated frother for the green drink she takes every morning. She reads voraciously, including all the weird, hybrid literary stuff I like to assign. By the second day of retreat, I started saying how I wanted to grow up and be like Sally. Everyone else started saying the same.

But Sally became my true aging idol one evening at dinner when we were all chatting about the historic lunar eclipse coming that night, the longest lunar eclipse in 600 years, which would start sometime around midnight and reach totality at 3 in the morning. A bunch of us were like, Let’s set our alarms and meet down by the beach at 2:30 to watch totality.

And Sally was like, Are you kidding? We have front row seats over the ocean! The moon is so bright. I won’t miss a minute of the show.

I’m telling you, something in me shifted.

We rescheduled our morning yoga so we could sleep later, and the whole group of us gathered on the beach for that entire eclipse, all three-and-a-half hours. It was one of the most memorable experiences of my life, and Sally is the whole reason we didn’t miss a minute of it.

Because she lives her life in a state of perpetual discovery, Sally showed us just by who she is that it’s better to say yes to the world as much as you can, it’s better to throw your heart wide open and show up, show up for the whole thing.

Writing about my childhood changed the whole trajectory of my writing career. I started making the best work of my life, work that drew praise from women I revere, like Dorothy Allison, Melissa Febos, and Lidia Yuknavitch. Without learning to write my childhood, I wouldn’t be the teacher I am, either. All the best things in my writing life manifested from writing my hardest story, despite the cost.

What aging-related adjustments have you recently made, style-wise, beauty-wise, health-wise?

This is going to sound unsexy, but I recently started eating more fiber. It’s kind of life-changing, that I’ve been pretty health-conscious since my twenties when I became a mother and a vegetarian simultaneously. But menopause really messes with our bodies. Menopause can feel almost like puberty, like, What is happening to me, and whose body is this, anyway?

I’ve found something magical about consuming 30 or more grams of fiber a day. It’s not about “staying regular.” I’m good in that department. It’s that the fiber makes eating feel more like how eating felt when I was younger, just a good energy and lighter and happier inside.

It’s kind of weird that this isn’t more commonly talked about and maybe it’s because there’s no money to be made from it—the benefits come from eating fibrous foods, not a supplement. Fiber from food remodels the gut microbiome and that, in turn, drastically reduces inflammation, and improves everything from sleep to mood to immunity to energy. Everything. It’s wild. And it’s not that hard. I can’t eat gluten due to Hashimoto’s disease, so no wheat, but a cup of green peas has 9 grams of fiber. An avocado, 10. Oat bran cereal has 7. A cup of raspberries, 8, and legumes, anywhere from 10 to 15 grams a cup. Chia seeds have 10 grams in 2 tablespoons and can be added to almost anything.

I’m not religious about it—I’m one of those 80-20 people—but I can tell it’s good for my body. So that’s my PSA for fiber.

I’ve also nearly eliminated alcohol because it makes me feel awful. I’ve always had a low tolerance, which I do consider a blessing given the addictive genes in my family, but these days, one glass of wine can tank my sleep. Without alcohol, I just feel better. I also started taking exercise more seriously around my 40th birthday. I bought a Bellicon mini-trampoline that I love so much, and invested in a yoga studio membership. More recently, I’ve been having fun with weighted jump ropes.

As for style, I just keep veering more toward comfort and ease. Anne Kadet wrote recently about wearing the exact same thing every day, and I’m not quite to that level, but I do wear the same things over and over. My more-or-less uniform in winter is a black cashmere sweater from Everlane and Athleta sweatpants or wide-legged jeans, depending on whether I can stand hard pants. In summer, I mostly wear a Toad & Co black sleeveless dress. I buy these items on Ebay and replace them when they wear out.

I’m an enthusiastic thrifter.

What’s an aging-related adjustment you refuse to make, and why?

I don’t want to cut my hair. I started getting highlights about ten years ago instead of dying it darker, and the lighter color looks nicer with my wrinkles, I think. But I’m not feeling like going short yet. Last time I got a truly short cut was probably thirty years ago and I really regretted it—probably because I was also very pregnant and had hormonal acne and the timing was terrible to chop off my hair. But I haven’t had it short since, and now menopause seems to be making it thinner, gah. My Nana had hair so thin you could see her scalp. I recently got sucked in by one of those Instagram hair pills. Time will tell if it gives me lustrous locks.

In all seriousness, though, all I really want is for my life not to become prematurely smaller. I want the opposite. I want to become as expansive as possible.

What’s your philosophy on celebrating birthdays as an adult? How do you celebrate yours?

I never had birthday parties as a kid, so I appreciate them now. Being born in the first place is an incredible happenstance. Usually, I have dinner with my husband and kids. They make wishes for me. I make wonderful gluten-free cakes, so I love baking one for my own birthday.

Who knows? My birthdays might get a little wilder as I get older. I’m not shy like I used to be, and I’m not as afraid of being in the limelight. I’m not as afraid of being loved.

Jeannine, thank you for the extended and really personalized answers. Sometimes you don’t know what you’re struggling with or leaning towards until someone else writes it down. I’ll be rereading this over a bowl full of raspberries and adding you to my substack favorites.

Thank you Jeannine.

Oh, the friend thing hits home for me - and many of us, I’d bet.

From 8 years old until about 11, I remember giggling all night long with close girlfriends; we never judged each other. And then… I don’t know something happened at 12 and everything fell apart until I was about 50. Now, I have wonderful girlfriends again; and we giggle and we don’t judge.

It’s sickens me to think that the “something that happened” was competition? We must teach our girls better!