This is 68: Karen Salyer McElmurray Responds to The Oldster Magazine Questionnaire

"I don’t so much feel old, as full of experiences I am only now learning to name more gently."

From the time I was 10, I’ve been obsessed with what it means to grow older. I’m curious about what it means to others, of all ages, and so I invite them to take “The Oldster Magazine Questionnaire.”

Here, writer responds. -Sari Botton

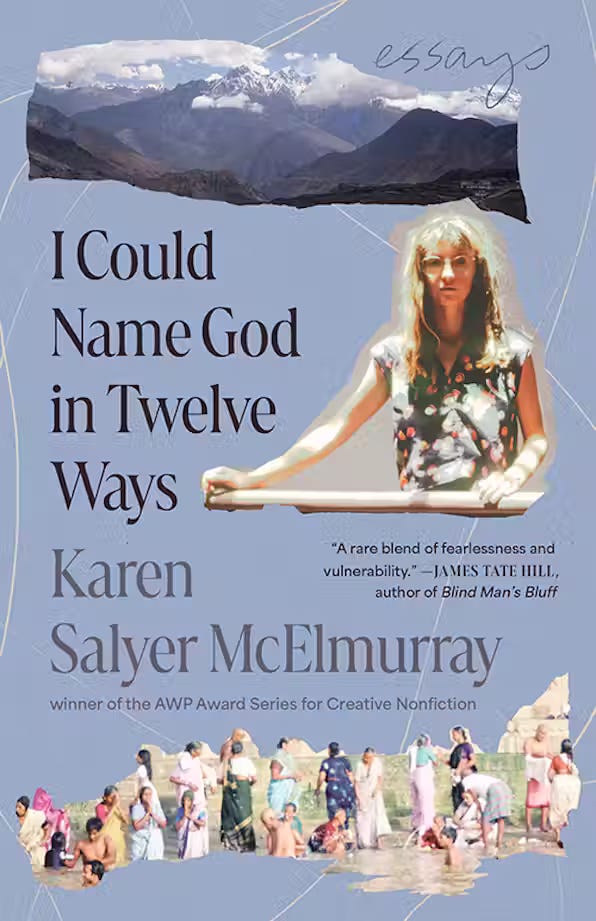

Karen Salyer McElmurray’s Surrendered Child: A Birth Mother’s Journey, was an AWP Award Winner for Creative Nonfiction. Her novels are The Motel of the Stars, Editor’s Pick by Oxford American, and Strange Birds in the Tree of Heaven, winner of the Chaffin Award for Appalachian Writing. As a fiction writer, she is the recipient of a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Kentucky Foundation for Women and the North Carolina Arts Council. Her work in nonfiction has been a recipient of the Annie Dillard Award for the Essay, the New Southerner Award, the Orison Anthology Award for Creative Nonfiction and the LitSouth Award. She has co-edited, with poet Adrian Blevins, an essay collection called Walk till the Dogs Get Mean. Wanting Radiance, a novel, and Voice Lessons, a short collection of lyric essays, came out in 2021. A new essay collection, I Could Name God in Twelve Ways, will be published by University Press of Kentucky in mid-September 2024.

--

How old are you?

I turned 68 years old on September 12, 2024.

Is there another age you associate with yourself in your mind? If so, what is it? And why, do you think?

My friend Cindra thinks of the number thirty-three as mystical, a cosmic turning point. I was 33 when met her at Hollins College as part of one-year MA Program. That was the year I finally began to take my writing life seriously. I began writing stories about my mother’s people in Eastern Kentucky. I wrote about faith and madness, about the magical and the all too real. I wrote the story of a woman named Ruth Blue who has visions of God and terrible angels. Ruth had never claimed her own power and I let the pages tell her story. I also wrote the story of her son, Andrew Wallen, who loves a young man named Henry Ward. I wrote the story of fundamentalist beliefs and forbidden longing.

Those stories later translated themselves into the pages of my first book, Strange Birds in the Tree of Heaven. Thirty-three became 43 and another friend, Wendy, urged me to tell my own story, to claim my voice like “a wicked and powerful bloom.” And so I began to write another book, Surrendered Child, and again pages lent power. I wrote about how, at 16, I’d placed my son for adoption. The pages gave life to the child I’d never seen. Fifty-three. Beginning a novel partly about the Harmonic Convergence. Sixty-three. A novel begun about a roadie who is a fortune teller. I don’t know for certain about numbers and particular ages. But I do know that writing has been a discovery of personal power, of stories and voice as I get older.

Thirty-three became 43 and another friend, Wendy, urged me to tell my own story, to claim my voice like “a wicked and powerful bloom.” And so I began to write another book, Surrendered Child, and again pages lent power. I wrote about how, at 16, I’d placed my son for adoption. The pages gave life to the child I’d never seen.

Do you feel old for your age? Young for your age? Just right? Are you in step with your peers?

This last few years I’ve worked on a collection of essays called I Could Name God in Twelve Ways. The collection is jam-packed with places I’ve traveled, lovers I’ve left behind, or ones who left me. It’s about Eastern Kentucky and home, that place changing, my family passing away.

I don’t so much feel old, as full of experiences I am only now learning to name more gently. So much has happened, including loss, grief, and joy, I haven’t lent enough credibility to what is happening right in front of me. At 68, I’m trying hard to learn the beauty of the present moment, all the while I'm fully aware of the vid nature of the past. I think my peers—my closest friends—are in a similar place. We’re all trying to breathe. To accept these years of taking stock and letting go. I think this time, this age, is just right. I feel such amazing, precarious, joy.

What do you like about being your age?

Most days what I like is an earned feeling. I don’t mean anything like a place and the things in that place, any feeling of having possessions or money. I mean that all that I know now, all that I have in my heart, my spirit, is earned at this point in my life. I hopefully have a clearer sense of what it means to love. What it means to come through grief. To see one moment of beauty or light and realize how important that moment is. I certainly am gaining a definition of the word “ephemeral.” I for sure like that whatever knowledge I have at this point is an accumulation of experience. I sincerely hope I am wiser and more compassionate as a result of that experience.

What is difficult about being your age?

What’s very difficult is the same challenge with time that I’ve always felt. Seasons, for example. It will begin snowing out and I’ll think with surprise, Oh! It’s winter! Time for a coat. Or a hot, hot summer, and I’ll suddenly realize I need to put on my shorts and walk my dog earlier. I’ve been no less surprised to look down at my wrists and see my grandmother’s slim, bony hands. Or to look in the mirror in my bedroom in the early morning light and be taken aback by seeing the same lines that were beside my mother’s mouth to be beside mine now. I’m 68? When did that happen? Time and change take me greatly by surprise, and I can find myself drifting in some desultory manner instead of being clear-headed in the years ahead on this earth.

What is surprising about being your age, or different from what you expected, based on what you were told?

I’m always startled by my body these days. How my breasts are lowering themselves, like they are bowing to age. My veins stand out, making themselves seen. The lines beside my mouth are deepening, the bones on the sides of my toes growing more pronounced. My whole self seems to be losing some vital moistness a younger-me could count on. I’m startled by this body’s aging, but am I surprised? Maybe.

When I was younger, in my 20s, I told myself I would not, not, give up on certain young-person things. The laps I swam and swam and swam. The sounds beneath the water, the ocean’s waves, and the pool’s blue floor. The four-mile runs. I have not given up on these things, but I am gentler with myself. An afternoon nap has grown appealing. And another younger-me thing. Falling in love, that rush and head-first dive? I love my person now with a sureness, an until laterness, until death-do-us-partness, that is comforting and frightening too. And the counting on. Tomorrow always came for younger woman me, even if with its hangovers and impatience and all those highways out.

These days, three old lovers have passed away. A best friend writes me often, remarking on how she is, do you believe it, OLD. Often, now, what I think about is my granny, Fannie Mae, back in Eastern Kentucky. I loved her more than anything. I think of her sitting on her flowered sofa, knit one, purl two, on long afternoons. I think of her face, how she’d rub on her moisturizer, tissue it off and exclaim about how good that felt. How she’d say older woman like her shouldn’t take more than two or three tub baths a week, if they wanted their skin to stay young. I think of Fannie Mae sitting on that sofa, and she was probably 68 then, just like me.

What’s very difficult is the same challenge with time that I’ve always felt. Seasons, for example. It will begin snowing out and I’ll think with surprise, Oh! It’s winter! Time for a coat. Or a hot, hot summer, and I’ll suddenly realize I need to put on my shorts and walk my dog earlier. I’ve been no less surprised to look down at my wrists and see my grandmother’s slim, bony hands. Or to look in the mirror in my bedroom in the early morning light and be taken aback by seeing the same lines that were beside my mother’s mouth to be beside mine now.

What has aging given you? Taken away from you?

Aging will inevitably take away family, friends, perhaps memory in and of itself. Grief is the price we pay for love. I saw that sign in the veterinarian’s office recently when I took my 10-year-old dog in to talk about her health. To love another being means that being will age, and that there will be a parting.

Oh, but what aging gives me! So much love, be it via memory or via the friends I hold close. And after all these years I am at last learning about laying aside what hurts. I am learning about forgiveness. Learning about letting go of what I cannot change. Learning to release the ghosts of childhood, of loss. So I tell myself.

How has getting older affected your sense of yourself, or your identity?

If you’ve heard of the VIDA count, you’ll know that age is stacked against us because of race and gender in terms of publishing, and it is certainly stacked against women in terms of age. What’s the popular term for those of us who are aging? Women of a certain age. Which is, according to the Urban Dictionary a “polite term for a woman who does not want her actual age known, e.g. one who is close to or just over the menopause.” Jeez, how many slights can there be one definition? Politeness. Concealing of actual age. And “the” menopause! But I digress.

My identity. It’s a concept that has long been given to me. My mother warned me to find a beau while I was still young. When I was in my late 30s, my father let me know that, because I was older and had waited so long and would never now have his grandchild, his name would die away in future generations.

When I was in my late 30s, I began teaching at a small Southern college and my sense of self shifted. Fewer students knew much about the examples of musicians or movies I offered in discussion. Bob Dylan? Who’s that? Once, when I was being observed for teaching by a fellow professor, I brought in all kinds of objects from my home and office: a spice jar; a small hand mirror; an address book; a hairbrush. Everyone had to imagine the character who owned an object they picked, including a fellow professor. When called upon, he said, “Well. All the objects look to me like ones owned by a middle-aged woman.” Ahem. Then there was the subject of my not being married, discussed often by my kin.

I chose the life alone for a long while, and knew, only really knew, when I met the person who would be my partner, when I was in my mid-40s. And now, at 68? Surely my identity has been formed by examples, by commentary, by off-hand remarks. Yes, getting older has affected my sense of self. But I will not let it define who I have been, nor who I may still be.

When I was younger, in my 20s, I told myself I would not, not, give up on certain young-person things. The laps I swam and swam and swam. The sounds beneath the water, the ocean’s waves, and the pool’s blue floor. The four-mile runs. I have not given up on these things, but I am gentler with myself. An afternoon nap has grown appealing.

What are some age-related milestones you are looking forward to? Or ones you “missed,” and might try to reach later, off-schedule, according to our culture and its expectations?

My mother had obsessive compulsive disorder. Child of coal miners in Eastern Kentucky, she spent her days keeping the world free of coal dust, of dirt, and clutter. This somehow meant there were no birthday celebrations. On one birthday I remember, I spent hours wishing aloud. There will be a cake. There will be. Cakes were too much of a mess. They meant dishes in a sink. Errant crumbs. I never remember celebrating. That has made all the birthday ahead bigger, much more weighted.

When I turned 40, it was early spring and my friends Carlyle and Ruth and I went rafting. I remember maneuvering rapids, laughing and shouting at the sky. I remember lingering at still areas, watching the clouds change. I remember stopping and securing our rafts, climbing a steep bank overlooking a watering hole. That was the way to have a birthday! Turning 40. Holding my breath. Knees in my arms and a take-my-breath cold plunge into the French Broad River.

There was 50, and my father driving from Kentucky to Georgia on my birthday week. He took me out for a steak dinner and we sat by the fire at my house, listening to mountain music on the CD player. Or years and years before that, as my sweetheart of nine years tried every year to make my birthday memorable. He bought me my first bicycle. He bought me lapis lazuli earrings in a marketplace in Jaipur. He made me a banana yogurt crème pie. He loved me as well as he could love a hurt person who grew up not being celebrated.

Or now. My sweet, amazing husband buys me roses. He brings me mint tea with honey when I’m sick. He waits through all the things I’m learning to unravel, like distrust, reluctance to celebrate. On my birthdays, he gives me cards—from him, from our dog. Each birthday unravels the first one I remember. Each day, in its own right, is a celebration of ordinary love.

What has been your favorite age so far, and why? Would you go back to this age if you could?

My favorite age would be somewhere between my late 20s and early 30s. I was a roadie then. I took the Greyhound Bus cross country to Arizona to take a job at the Grand Canyon. Took a bus from Kentucky to Maine, where I saw the rocky coast. I drove my 1967 Dodge Dart from Kentucky to Arizona. I slept in my car at rest areas, put up my tent in state parks. I more than once had literally no place to go. Then I drove the Dart from Kentucky to Virginia, the Dart’s engine catching fire on the way.

I lived in a cottage behind the great big house of a Charlottesville lawyer and started graduate school in creative writing. I moved to the country, worked at a country store. When I was working at a greenhouse, I fell in love with a fellow traveler. We traveled to England, to Ireland, to Yugoslavia, to Greece. We worked in Australia, in France. We meandered through Nepal and India. We grew sick, made our way home, fell out of love.

In the times ahead? My 20s became my early 30s and more schooling, writing, writing. My life was set in motion. I taught and taught. I moved from house to rented room to house after house. Would I do all of these days again? Days of bottomless energy, of delicious lostness, no more sense of tomorrow than of yesterday. Would I take on those days again? Oh, yes. Yes. For sure.

Often, now, I think my granny, Fannie Mae, back in Eastern Kentucky. I loved her more than anything. I think of her sitting on her flowered sofa, knit one, purl two, on long afternoons. I think of her face, how she’d rub on her moisturizer, tissue it off and exclaim about how good that felt. How she’d say older woman like her shouldn’t take more than two or three tub baths a week, if they wanted their skin to stay young. I think of Fannie Mae sitting on that sofa, and she was probably 68 then, just like me.

Is there someone who is older than you, who makes growing older inspiring to you? Who is your aging idol and why?

In an evening writing seminar not too long back, someone brought a great pair of dark sunglasses with red frames and, during break, we all tried them on. Then we voted on who looked like what famous actor in the glasses. Voters were fairly consistent that one person looked like Bryan Cranston, from Breaking Bad. There was a more mixed show of hands when it came to another person looking liking Lily Gladstone in some movie or other. When it came to my turn with the sunglasses, the actors suggested were several: Meryl Streep; Holly Hunter; Helen Mirren. Those were some amazingly flattering suggestions. Each of those women is graceful, articulate.

But still. When I was walking home later that night, I thought more about their choices for me. Really, I thought. I mean, Helen Mirren? She’s seventy-eight78 years old! I decided to pick another older woman altogether for myself, one who I admired, and I ended up picking someone I’d known my whole life. My grandmother, I thought. In our creative writing seminar workshops, grandmothers could be a cliché, but Fannie Mae Salyer got my vote as inspiring and aging idol every time. My grandfather, Clarence Wiley Salyer, died pretty young—only 59. That left my Granny on her own, an independent state she maintained until she passed at almost 90.

She maintained her home, carted coal into her fireplace. She had close friends. She helped a neighbor do weekly Chesty Potato Chip deliveries to all the local schools. She quilted, crocheted lace. She road along on a yearly camper/camping trip to Canada, where she fished and sat up late by the campfire. She canned soup, beets, pickles. She hoed a mean garden. She took me in more than once when I had no place to go. She was unqualifiedly the most generous soul I’d ever met. I don’t doubt she would have looked fabulous in those sunglasses.

What aging-related adjustments have you recently made, style-wise, beauty-wise, health-wise?

I’m always walking far ahead of friends, be it through the parking lot or on a hiking trail. When I broke my ankle once, my friend Carlyle joked that she’d finally be able to keep up with me! That walking fast, I’ve decided, is a metaphor for worry about how left behind I might get.

Another friend, Patricia, once wrote an essay called “Behind.” She was writing about something at once so concrete, and so very ephemeral—that push to publish, to be known, to be at the next conference, to be first in line for as many definitions of success as possible. How do we know when we’ve accomplished enough? Done enough? Carried enough weight? How do we just plain slow down, walking or otherwise?

Lately, I have come to enjoy the taste of the word fallow in my mouth. I tell myself that letting work sit, gain the power of reflection, is entirely as important of the number of words produced in a given day. I am certain that I could never be part of NaNoWriMo, no less follow the advice of a long ago mentor to write the first hundred pages of a work as quickly as possible. Fallow. Rich. Unripe. Ripe. I love standing in my perennial garden and studying the shapes of blossoms, the contrasting colors. I love the feel of deep breaths, pauses, exhales. I’m learning, slowly I might add, about the importance of stillness.

What’s an aging-related adjustment you refuse to make, and why?

So far, I am not “retiring” in the way you might think of retirement. I haven’t stopped teaching. I haven’t quit traveling with my work—doing readings, going to conferences, attending book festivals. I want to get out there and represent my work as much as I ever have, and I want to be an active part of the ongoing community conversation about words that is a vital part of writing itself.

I am naturally not now, nor have I ever been especially retiring in my personal life. I believe strongly in telling my stories to offer experience, and maybe, maybe, healing to other people. All of this said, I am, for perhaps the first time in my life, pursuing a balanced life. I want balance in work, family. I want balance in making art with words. And I want a balance of joy and sorrow, light and dark.

I would not call this an age-related adjustment at all. Instead I’d call it movement toward the core of living itself. In that sense of wanting balance, I feel the youngest and the most alive I’ve ever felt. I refuse to be anything else.

Oh, but what aging gives me! So much love, be it via memory or via the friends I hold close. And after all these years I am at last learning about laying aside what hurts. I am learning about forgiveness. Learning about letting go of what I cannot change. Learning to release the ghosts of childhood, of loss. So I tell myself.

What’s your philosophy on celebrating birthdays as an adult? How do you celebrate yours?

As I mentioned earlier, when I was a kid, there weren’t birthdays, not like I imagined them. There weren’t sparklers or balloons. No-you-can’t-blow-them-out candles. No friends jumping out from behind the couch to shout HAPPY BIRTHDAY. Partly due to my mother’s mental illness, and partly due to the deep unhappiness between my parents that inhabited our home, there were no celebrations. That has made them all the more important to me through the years.

I remember a long-term relationship, how my then lover knew I’d never learned to ride a bike. He led me into his apartment with my eyes covered, and there it was, a regular bicycle with a bow tied on the handlebars. There were a few friends. There was banana crème pie. When I traveled the world with that same lover (partly what my new book of essays is about), we stayed for six weeks with friends in Greece, on the island of Crete. It happened to be the meltemi season then, the time of winds, and it happened to be my 32nd birthday. Those friends and I—Jody, Alison, Carla, and who remembers who else—sat opening bottles of retsina at a long table near the wharf. We ordered plate after plate of calamari and white beans, feta and olives. That birthday made the city of Chania all the more magical, its deep blue waters rippling in the winds.

There have been so many other birthdays. Quiet birthdays at the corner table in a favorite restaurant. Celebratory birthdays alone as I walked the beach or sat with my now-gone beloved dogs, Jenkins and Rufus. My philosophy as I write these birthday words, seems summed up with one word. Happiness. Happiness is not something I’ve always allowed myself. I’ve been prone to regret. To savoring the bitter taste of memory. At 68 I want to taste all of it. Being happy, surviving. And love. I want every bit of that I can find, like a gift I open little by little.

"To accept these years of taking stock and letting go." That is Karen's magic. We're a year apart. I hope to be like her someday.

I am 81 and really enjoying it thus far. There is a freedom doing whatever I want, whenever I want.

I still cook, and bake, but not when I don't want to.