The Golden Girls of Punk

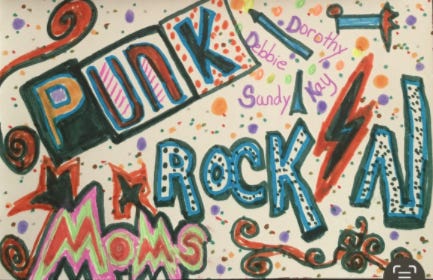

Four Baton Rouge women defy stereotypes, three minutes at a time, in an act called Your Mom Band.

Some bands set the mood with a fog machine. Others use a light show, or pyrotechnics. Your Mom passes out homemade cookies from a Tupperware container. The band’s bassist, Dorothy LeBlanc, makes them herself—oatmeal chocolate chip, her mother’s recipe, she proudly announces over the mic. It’s a Friday night at Phil Brady’s in Baton Rouge, and the place is packed. The four 60-something-year-old women on stage are ready to rip. The crowd is eclectic, more women than men, of ages ranging from early twenties to card-carrying AARP members.

After a brief sound check, LeBlanc belts out, “One, two, three, four!” A galloping ferocity of sound follows. You could power New York City from the energy in this room, and things are just getting started.

Your Mom is part of a family of bands trained by multi-instrumentalist guru David Hinson, through his music-learning program, Adult Music Club (AMC). The AMC is like a farm league: people come to learn, group up, form bands, and eventually get released to the big leagues of booking and running their own shows.

Your Mom is part of a family of bands trained by multi-instrumentalist guru David Hinson, through his music-learning program, Adult Music Club (AMC). The AMC is like a farm league: people come to learn, group up, form bands, and eventually get released to the big leagues of booking and running their own shows. All of the AMC bands rehearse at a former nail salon with pink walls, overlaid in sections with bright-orange egg-crate foam, to absorb the sound. Hinson has been doing this since 2012. Hoping to foster a musical community in Baton Rouge, he teaches children by day, and adults by night. Besides Your Mom, he currently manages three other projects, Horseshoe, Dwayne Dwayne, and Love Tap, but in the ever-growing music-learning community of AMC, new bands crop up all the time.

Your Mom, for instance, emerged from an AMC practice group that Dorothy LeBlanc, Debbie Roussel, and Sandy Brock joined around eight years ago. They began with ‘80s soft rock covers and eventually the group swelled to ten musicians.

The three women had all come to Hinson from different places. LeBlanc had been playing guitar since after she was treated for breast cancer and entered remission in 2003. “I was on the radiation table and it just dawned on me that if I was ever to be a musician I should probably do it,” she recalled. For years she had gigged around town at cafés, children’s parties, and retirement communities, and now she wanted to figure out the cello. Roussel, on the other hand, had never played an instrument in her life. She worked for the legislature downtown at the capitol, but she had always loved rock ‘n roll, singing her childhood away into a hairbrush and turning up the radio in her car to full volume as an adult. When she started working with Hinson, she struggled her way through learning the guitar, following a childhood dream—but, after a turn with the baritone ukulele, found her place on the drums. Brock, a retired medical assistant, had taken a couple of years of private lessons on the guitar and sought out group lessons with AMC. She later played keyboards in another AMC band, overlapping with Your Mom, called Unselfish Lovers of the Blues.

After the group had been playing and practicing together for several months, Hinson announced that they were now a band. He called them Grand Suburban. “I looked at him like he’d lost his mind,” said Brock. She thought that she was there to learn to play, not start a rock band.

LeBlanc had been playing guitar since after she was treated for breast cancer and entered remission in 2003. “I was on the radiation table and it just dawned on me that if I was ever to be a musician I should probably do it,” she recalled.

But they kept practicing anyway, and even played a few gigs as Grand Suburban around town. They enjoyed the music, but there were so many members they could barely fit on a stage. One day, about a year into the Grand Suburban project, Hinson plucked the three women from the group and formed a new band, a punk band no less. These three women, who had grown up on the Beatles and the Stones, would now play the Stooges and Ramones. “I didn’t like it,” said Brock. “Every practice we would play some sample songs and I’d listen and think, Oh my God, shoot me now.” Hinson suggested the name Your Mom. Roussel would play drums. LeBlanc would move to bass. Brock would stay on guitar.

Brock and Roussel were skeptical this new project would even work out at all. But they had come there to challenge themselves, and they trusted David’s instincts. So they decided to give it a shot. Then, they told me, something remarkable happened. They actually began to enjoy playing this crazy punk rock music, along with the technical difficulties it presented.

But something was missing. They needed more firepower. They needed a lead guitar.

For years Hinson had been trying to get Kay Lindsey back in the musical game, and for months he’d asked her to join Your Mom. Lindsey, an ophthalmic technician, began playing guitar at the age of 11. She worked as a professional musician from 18 to nearly 30, playing in loads of bands, touring Europe in the 70’s with two of them. She played Jazz Fest twice with her band, The Proud Marys, and played in projects around Baton Rouge for years. But it had been too long since she had been on stage.

Roussel had never played an instrument in her life. She worked for the legislature downtown at the capitol, but she had always loved rock ‘n roll, singing her childhood away into a hairbrush and turning up the radio in her car to full volume as an adult.

Despite her initial reluctance, the nudges from Hinson and a music shop buddy’s insistence (“You gotta be in that band!”) eventually landed Lindsey back in the practice room with a guitar in hand—part of Your Mom. “I went and I had such a good time,” remembered Lindsey. “The women are just so much fun. I feel like I’ve known them all my life. We were all instant friends.”

Not only did Lindsey enjoy the return to music, she got to play music with other women, just as she had so many times in her musical career. And she found at this particular stage in their lives, there were notable advantages. “One of the good things about maturity—at least in my viewpoint—is we don’t have a lot of ego issues of who gets to be the star,” she said. “It’s kind of automatic. Whoever wants to do something can.” The women all write their songs together, and they take turns singing. Every single member has a voice.

Your Mom now has more than half a dozen originals, and counting, all distinctly flavored by ‘70s punk and oldies rock-and-roll rhythms. Tight one-to-two minute jams with lots of cymbals and chunky power chords. Lindsey works in her signature solos in just the right spots. One woman will sing and the others join in. For the most part, these are head-bobbing, dancy punk rock tunes, and their fans can’t seem to get enough.

Using the elderly female stereotypes as a kind of driving force for their satiric style of punk rock, their songs have titles like “Drugstore,” “Dessert,” and “Aluminum Foil.” Perhaps their most political tune is a song called “Meg White,” named after the female drummer of the rock duo the White Stripes, who began, much as Roussel did, with no musical background and a lot of gumption. Music critics and fans were infamously unkind to Meg White. They drove her out of the business. And that really pisses Roussel off. She sings on this number, and beats her drums as though she’s at war.

“One of the good things about maturity—at least in my viewpoint—is we don’t have a lot of ego issues of who gets to be the star,” Lindsley said. “It’s kind of automatic. Whoever wants to do something can.”

You can talk about her

But don’t be mean

You oughta be real nice

To the ladies on the rock-n-roll scene…

Most people have been “nice” to Your Mom. But on occasion, people treat them with the typical condescension reserved for children and people above a certain age. “When you start aging, people treat you differently,” said Brock. “People pat you on the shoulder and call you ‘sweetie.’” She laughed. “I think it’s important to show them something different, because, guess what, it’s going to be you. You’re not always going to be 27 years old and wearing high heels. One of these days you’ll be my age and wear sensible shoes. But rock-n-roll is still there. Rock-n-roll isn’t going anywhere.” To those who laugh at them on stage, she wonders, “What is it that’s funny? Is it because we’re playing [at all]? Is it because we’re playing rock-n-roll? What do you want us to play, Lawrence Welk? I’ve been listening to rock-n-roll since I was 4 or 5 years old. Why should I stop now?”

Punk as a genre boasts countless apocryphal beginnings, but hanging around Your Mom has me dwelling on 1975, when the artist Malcolm McLaren formed the Sex Pistols from a rag-tag bunch of teenagers that hung around the burgeoning London punk scene. McLaren helped write their songs and design their aesthetic. They barely knew their instruments at first, but they learned along the way. They got some flack for this, but really, that was kind of the point. Punk was raw, an affront to perfection. Over the decades, punk has become so professional and polished that Green Day debuted a punk-rock musical on Broadway in 2010.

Punk has also always been about confronting our every standard and stereotype, at least in theory. But isn’t it a stereotype that punk is the province of youth? Your Mom is all too eager to dispel that myth, and so in this sense, and in the sense of the sheer rawness in their music, they are as punk as any punk band I know.

“When you start aging, people treat you differently,” said Brock. “People pat you on the shoulder and call you ‘sweetie.’” She laughed. “I think it’s important to show them something different, because, guess what, it’s going to be you. You’re not always going to be 27 years old and wearing high heels. One of these days you’ll be my age and wear sensible shoes. But rock-n-roll is still there. Rock-n-roll isn’t going anywhere.”

The women in Your Mom aren’t shy about how the band has improved their lives. It keeps them active, creative, and constantly thinking about what will come next. Maybe they’ll put out a record, they say, maybe go on tour. It’s a whole new set of challenges and opportunities they never could have imagined only a few years ago. LeBlanc puts it this way: “It’s the most courageous thing I’ve ever done. And when you do something courageous, you walk a little taller.”

I sat in on a band practice and got to watch how they worked together. Against the glow of Christmas lights strung from wall to pink wall, they laughed and cussed and screwed up and laughed some more. All the while, Hinson tweaked and massaged their songs like a conductor. In his patient voice, he said things like: “Let’s go all out” and “Remember, we’re quoting Iron Maiden on this one.” And it worked. They went all out, and enjoyed the hell out of it. They’d be back next week, another rowdy good time.

This makes me so goddammed happy.

I saw Your Mom in Baton Rouge a few years ago. I am a 62 year old rock drummer, and they MADE ME SO HAPPY.