The Power in Putting a Name to Something

Learning something new about myself as I approach 60: I'm on the autism spectrum.

I started out this new year of my life by discovering something new about myself—well, not exactly new; it’s something I’d long had a hunch about. I decided that in the interest of embarking on this new path with clear eyes, I should finally get to the bottom of it.

My whole life, in a litany of ways, I’ve felt slightly different from everyone around me—family, friends, classmates, co-workers, and beyond. My tastes, preferences, tendencies, choices, and ways of interacting with people have rarely aligned with those of the general population, and it’s made me incredibly self-conscious. Sure, there are people I identify with, and who identify with me; they’re usually people who think of themselves as different, too.

For some time now, I’ve been eager to understand why. Over the past two weeks I took a step in the direction of finding out.

***

My fascination with what it means to be a particular age is very much related to this feeling of being different. It began for me in childhood, when I realized that in certain areas, I was progressing differently than my peers. I was achieving some things ahead of the other kids (I was the first in my kindergarten class to read), but was way behind on others (I was a late developer; I was so uncoordinated that in gym class, I couldn’t perform most of the basic athletic moves my classmates could without making a complete fool of myself—to the point that in 9th grade, my gym teacher failed me and made me stay after school for remedial P.E. Across the floor from where the cheerleaders practiced. It was a nightmare.).

Ever since I published Griffin Hansbury’s Oldster Magazine Questionnaire, I’ve been thinking about a term he used that I’d never heard before: chrononormativity. Hansbury wrote:

I find it useful to think of Elizabeth Freeman’s concept of “chrononormativity,” which describes the way that capitalism and patriarchy convince us that there’s a right way to progress through life and that way maximizes productivity and reproductivity. Queer and trans people are often outside of that, but we also measure ourselves against it and that can feel like failure. At the same time, there’s a tremendous liberation to being out-of-sync with what is normal. You have more space to do what you want with your life.

Freeman and Hansbury are referring specifically to something queer and trans people experience, and as a straight, cisgendered person, I don’t want to appropriate that. But the concept is very relatable to me, as someone who has not followed a traditional path, personally or professionally, which puts me at odds with others and with our culture’s expectations around which milestones we are supposed to reach at which specific times. I strongly identify with that feeling of failure.

This feels even more pronounced as I, a childless freelancer married to another creative weirdo, approach 60—an age at which so many of my peers are guiding their 20-something children from higher education to their first real jobs…becoming grandparents…either retiring or preparing for retirement from traditional jobs.

It’s not that I want what they have. I genuinely don’t. This has always been the case. I love the offbeat life I’ve designed for myself (minus the lack of ample preparation for retirement). But I’ve still always held myself up to everyone else and wondered whether not wanting the same things they do means there’s something wrong with me.

***

“Wrong” is, of course, the wrong word. On some level I’ve always believed that, while on another level I remained self-conscious and insecure, and judged myself harshly.

I wanted to stop doing that, to be kinder and more accepting toward myself, and also to gain insight into some of my more unusual differences—sensory things, like being fundamentally thrown off by certain sounds and fluorescent lighting (or any artificial lighting during daylight hours), and my visceral repulsion from certain basic foods (egg whites, bananas, milk); interpersonal things, like my anxiety about knowing when it is and isn’t my turn to talk in conversations, and a perplexing uncertainty about who does and doesn’t genuinely want to be my friend, beyond superficialities I find hard to parse.

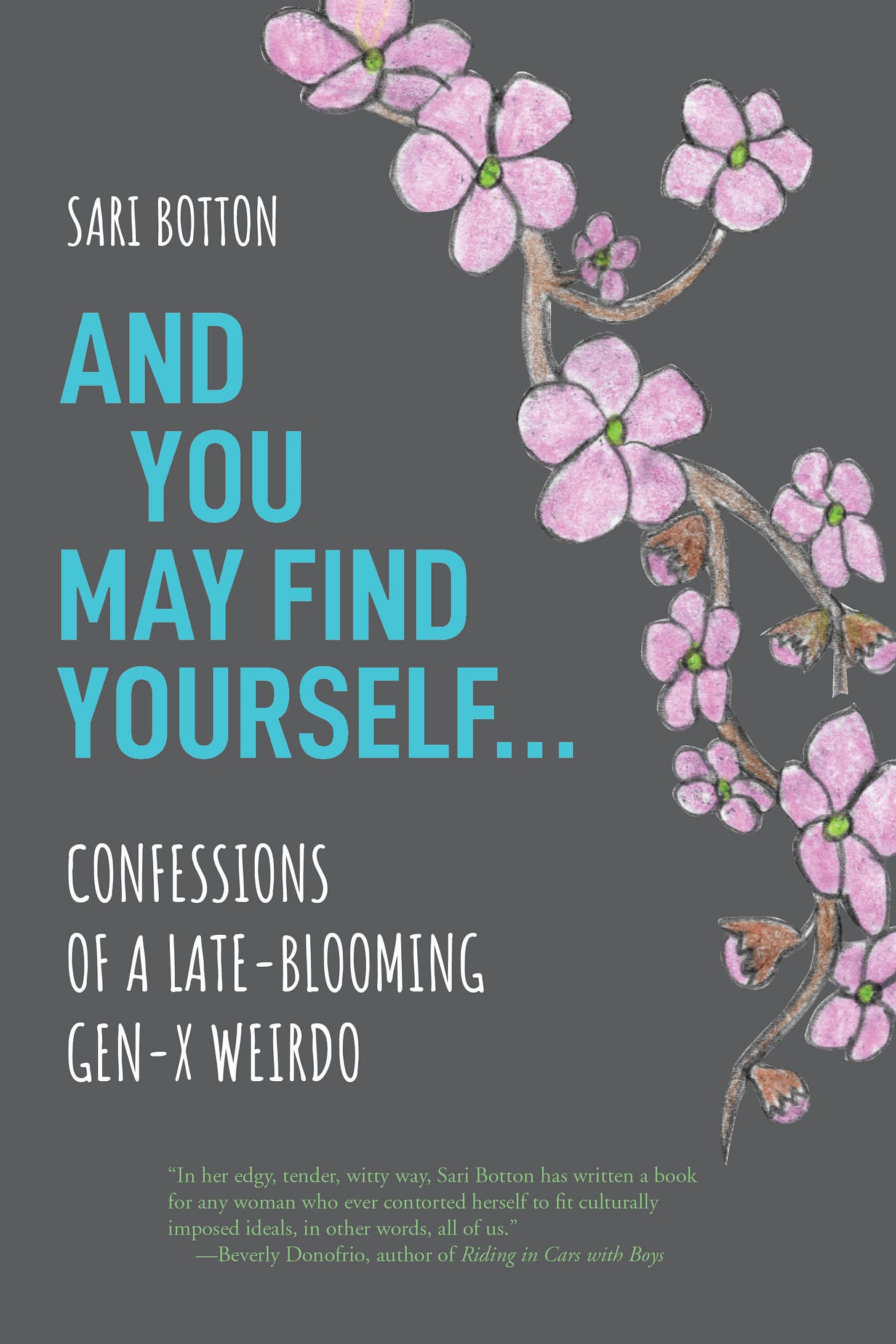

I wrote about all of this and more in my memoir-in-essays, And You May Find Yourself…Confessions of a Late-Blooming Gen-X Weirdo. It led a few readers who identify as being on the autism spectrum to ask whether I’d ever been tested. I told them I’d always wondered whether I might be on the spectrum too, and thought that someday, I might look into it.

I’ve had this in mind for some time, but didn’t do anything about it until I read “What My Adult Autism Diagnosis Finally Explained,”

’s excellent essay in The Cut, and listened to A.J. Daulerio’s insightful interview with her on The Small Bow podcast. Choi was diagnosed with autism at 43, and it helped her and everyone around her to understand why she behaves in the various slightly-off ways she does.After reading and listening to Choi, I thought harder about getting tested. I remembered ghostwriting two memoirs by mothers of neurodivergent kids—and relating more to the kids than to their moms.

I realize I’ve completely buried the lede, but here it is: I’ve just undergone an evaluation through The Sachs Center, the same organization Choi used, and learned that I am at the low end of the autism spectrum, Level 1.

I’m not the least bit surprised by this. Neither am I upset by it. No, instead I feel validated. I’ve had my curiosity sated, my hunch confirmed. This makes so much sense to me. There is power in being able to put a name to something about yourself that you haven’t quite been able to put your finger on.

That said, I am not likely going to do anything concrete about it. I’ll pore over the resources The Sachs Center has shared with me. Surely I’ll go down rabbit holes on the internet about Autism Spectrum Disorder. Maybe I’ll learn some tips for being more comfortable in the awkward distance between how other people operate and how I do. But I don’t want to change my brain and how it works. I just want to understand it. And to be able to accept myself the way I am.

Maybe what I learn will help me navigate this new path before me in a different way. Stay tuned…

You write: "My whole life, in a litany of ways, I’ve felt slightly different from everyone around me—family, friends, classmates, co-workers, and beyond." I used to think every writer felt that way. Now I think that every human being feels that way. And it is the glorious truth! No one is "average."

You have given so much to others, Sari. Kinder and gentler to yourself. I wish that for you! ❤️