For Better and For Worse #3: The Shadow of Death

An excerpt of Sorayya Khan's "We Take Our Cities with Us: A Memoir"

This is the third in a new Oldster Magazine series called “For Better and For Worse.” It features essays and interviews about longstanding relationships. While I know that couplehood isn’t for everyone nor the only way to live, and that it is over-privileged in our culture, I’m interested in how partners navigate their relationships over time. Check out the whole series. -Sari

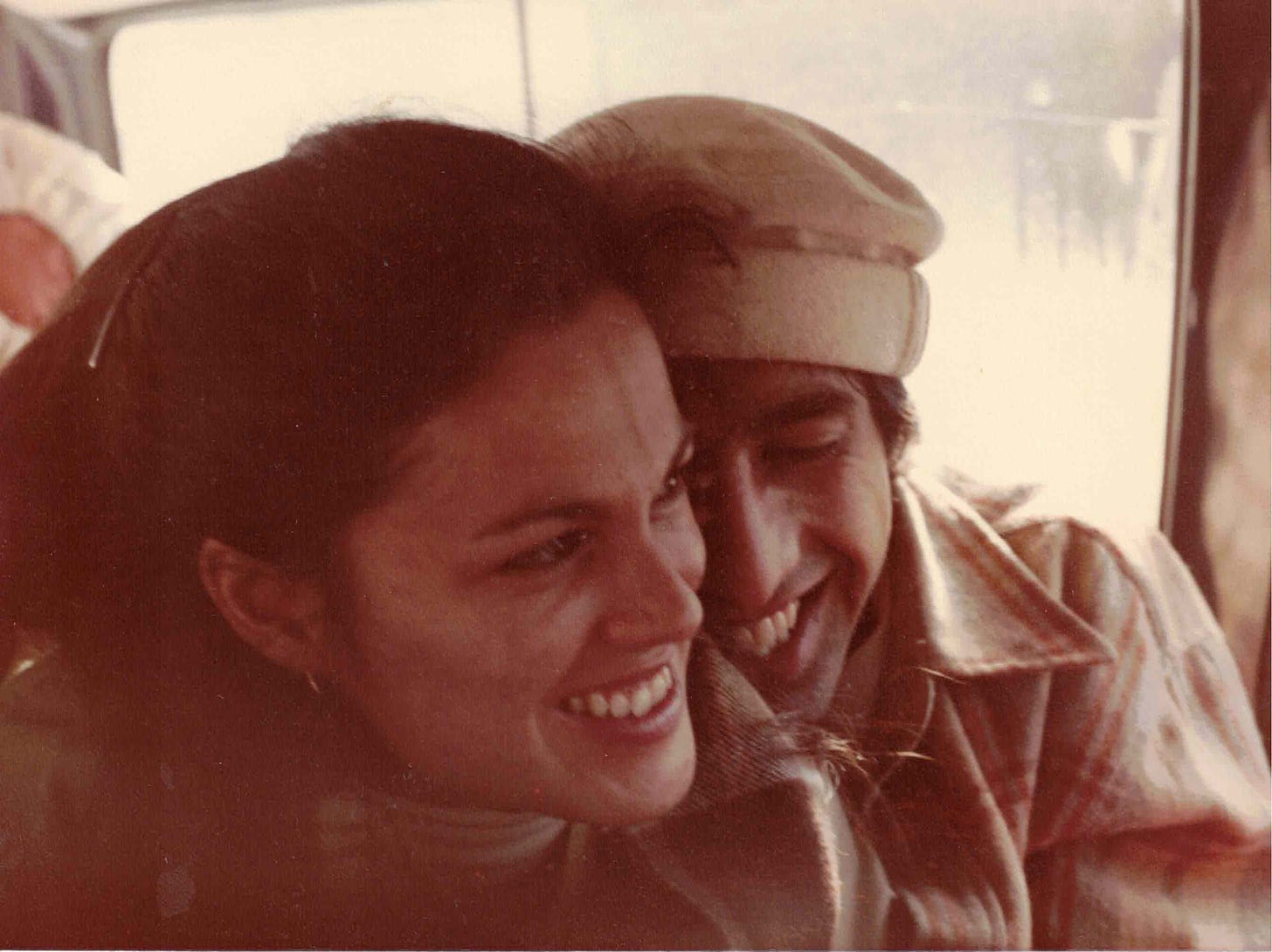

I can summon the sounds of that Syracuse day as if they made a favorite piece of music, but the melody brings dread, not joy. A gush of water fills our acrylic bathtub. Naeem’s moans match the slip of oil on skin as I massage his back. The telephone receiver drop-clicks in the wall mount. The bathroom door catches and stops as he uses the bathroom again and again. The soundscape survives and so, too, does the cast of details it unleashes. I have a precise memory of a single thought: This man who is my husband and works almost every hour of each day, cannot find it in him to return home on time from a Sunday morning at the gym.

Our living room is extraordinarily bright and the shafts of swirling dust buzz. The ceiling-high bookcase appears to have fallen into the glass tabletop where colorful novels rise in stacks. Naeem is wearing black shorts, a signature bandana (likely red), a gym towel (not ours) draped around his neck. His face is ash gray, an unnatural version of itself. When he lies facedown on the living room floor, one side of his half-open mouth is distended against the carpeting. His smooth back, always beautiful, is surprisingly salty when I kiss it.

Strange, then, that the night which followed is mute. This, despite the fact that I spent it at a Ravi Shankar concert ninety miles away in Rochester. I went without Naeem, though he had a ticket, too, because we were loath to let our tickets go to waste. Perhaps that’s why my mind erased it—because I feel I shouldn’t have gone, that I shouldn’t have enjoyed a note. I cannot recollect the simplest detail of the sitar maestro, whether there was more than one performer, where our friend Laura and I sat in relation to the stage, or if there was an intermission. But it seems important, this music that I went to hear while, without my knowledge, my husband’s heart was dying.

I have a precise memory of a single thought: This man who is my husband and works almost every hour of each day, cannot find it in him to return home on time from a Sunday morning at the gym.

On the off chance that a recording was made, and that it still exists twenty-seven years after the fact, I write the Eastman School of Music. I provide the only two details I’ve retained: the date and location of the concert. I immediately receive a scanned copy of the concert program. I stare at the first page of the email attachment. By my calculation, the concert’s 7:30 p.m. start time on April 29, 1990, is approximately ten hours after Naeem had a heart attack on a treadmill in a gym near the YMCA in Syracuse. I know now, but didn’t know then, that the concert and my long, pleasant drive to Rochester with our friend (We mustn’t waste the tickets! Go on, Naeem told me) fell within the twelve-hour window in which patients who do not receive medical treatment for cardiac arrest usually die. To my surprise, a concert recording exists and, if I’m patient, it can be digitized, and I can listen to it in the Eastman library.

It takes almost six months for the recording to become available, but the day finally arrives when I again drive alone to Rochester. It’s late September and uncannily like that unseasonably bright and warm day in April. The central New York sky is uncommonly clear, the only clouds trailing wisps produced by aircraft. Rich farmland rolls toward Cayuga Lake east of Route 96 and Seneca Lake on the west, all of it being put to sleep by farmers in anticipation of winter. On the thruway, trees rush by my windows like a moving painting, but it’s early autumn and the tips are brushed with golds, reds, and yellows, as if an artist changed her mind at the last moment and added bursts of color at the top of every tree. I’m reminded of my pregnancies’ hallucinatory dreams, in which magnificent liquid colors bled in and out of each other in a luminosity I haven’t seen since.

On the recording, Ravi Shankar introduces the first piece, and his Indian accent, so similar to a Pakistani accent, comforts me. The raag’s opening, the alaap, is a dialog between the musician and the raag that sets the scene, much like opening paragraphs in a novel. I’m in downtown Rochester, in the listening room of Sibley Music Library, surrounded by cubicles like the one I’m sitting in, outfitted with complex audio equipment. I’m sitting on the floor, almost under the desk with the sound system into which I’ve inserted the CD, and I stay there for the alaap and everything that follows in Raag Puriya Kalyan, momentarily transfixed by an overwhelming pathos of classical Indian music.

When the tabla and sitars are in full thrall, they pull each other through terrific crescendos and explosive trills. How could I have forgotten this? I wonder. Later, the audience roars, and I realize I’d forgotten that as well, though it must have moved me to have shared the moment of reverence. I only realize that I’m swaying back and forth with the music when someone comes to my corner of the listening room to look disapprovingly at my squeaking chair. When Laura shares her memory of the concert with me, she recalls only the tabla. She thinks this is because the concert was her introduction to the instrument, but after listening to the recording, I tell her it’s because of the solos.

By my calculation, the concert’s 7:30 p.m. start time on April 29, 1990, is approximately ten hours after Naeem had a heart attack on a treadmill in a gym near the YMCA in Syracuse. I know now, but didn’t know then, that the concert and my long, pleasant drive to Rochester with our friend fell within the twelve-hour window in which patients who do not receive medical treatment for cardiac arrest usually die.

The forgiving afternoon light means the drive home is more beautiful than the drive to Rochester, but I’m preoccupied by something else: the story I’ve just discovered about Ravi Shankar’s son, Shubho, who was also playing that night. Ravi Shankar died in his nineties some years ago, but his son, Shubho Shankar, is also dead, at 50, from a protracted illness and pneumonia, and, it seems to me, from heartbreak. After giving up his sitar, he’d returned to it in his forties, left California for India to study with his mother (after a twenty-year absence during which they’d been estranged) and eventually enjoyed a resurgence in his career, which included touring again with his father. In December of the same year we saw him, he played an Indian festival where critics claimed he played off-key. Recordings show this wasn’t the case, but he was inconsolable. He declared it too late in life to continue musical training, left India and his mother, gave up the sitar, and was dead less than two years later.

My memory of that evening is unaltered by what I hear—there is no music, no sound. When I returned from the concert, Naeem was much the same as when I’d left, perhaps worse. In my absence, he’d been instructed over the telephone by an emergency room physician to take Imodium, drink fluids, and sleep. For the rest of the night, he paced, visited the bathroom, and tossed in bed. All the while, he behaved like a complete stranger, one overcome by what he described as a crushing yet non-specific sense of dread. At the time, his amplified anxiety, terror even, seemed melodramatic. Who was this person I married? Is this how he intended to behave when life threw him viruses that gave him diarrhea and made him vomit? Perhaps we slept some that night, but what I recall is that Naeem’s sweat drenched the bed and made me cold.

During a doctor’s appointment the next day, Naeem was diagnosed with a viral illness and told to rest, which made us certain he was hardly sick at all. A week passed, and still, Naeem could hardly climb the stairs of the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at the university where classes had ended and final exams had begun. He ascended the four flights excruciatingly slowly, pausing at each landing before using the bannister to climb the next set of stairs.

At the top, he allowed himself a longer rest by sinking into a secretary’s chair until his heart stopped racing and he was able to walk the remaining hundred yards to his office. He complained about his vision, episodes in which a dark shadow zig-zagged, floating from the periphery to the center, followed by sharp headaches that lasted hours. The symptoms and trips to the doctor persisted for a month that included a Memorial Day picnic at Jamesville Reservoir and a softball game with friends from my writing workshop. Naeem labored for breath as we set up the diamond and was picked last for teams. I groaned with everyone else when he hobbled toward first base, an easy out.

When I returned from the concert, Naeem was much the same as when I’d left, perhaps worse…At the time, his amplified anxiety, terror even, seemed melodramatic. Who was this person I married? Is this how he intended to behave when life threw him viruses that gave him diarrhea and made him vomit?

Naeem was thirty-three the night I went to the concert. He was thirty-four a month later at his fourth doctor’s appointment, the only time I accompanied him. He was seeing Dr. Chen again, the man who had been insisting for weeks that it was just a virus. I was startled to hear my name called in the busy waiting room, and I joined Naeem just as he was being helped from the examining table.

Dr. Chen was hunched over pages of EKG graphs, fine point pen outlines of delicate mountain peaks and plunging cliffs on red squares of graph paper. Dr. Chen was a slight man, more so when he sat and his white doctor’s coat billowed. But he was like us, a foreigner in Syracuse, New York, and without wanting to, we felt sorry for him. “The patient knows best,” he remarked, shaking his head. What did he mean? Fear hadn’t taken hold yet. Naeem was taciturn, as he is in moments of crisis.

“What do you recommend?” he finally asked, as if our sympathy as fellow foreigners meant we could still trust him.

“You’ve likely had a heart attack,” Dr. Chen said. “You must see a cardiologist.”

“When?”

“Now.”

I ran a red light on W. Genesee an hour later (and a month too late) on the way to the cardiologist’s office.

“Are you trying to kill us?” Naeem asked sensibly, “Because I’d like to live.”

The imaging room was far too small and crowded with medical professionals, but I stayed anyway. After a fluster of activity, the technician glided her ultrasound wand over his shaved chest. The bulky machine produced a grainy picture that silenced everyone. The cardiologist leaned forward and tapped his fingernails against the screen while he drew an outline around the damaged heart muscle that filled it.

“Cocaine,” he said confidently.

“No,” Naeem said. There was no drug usage, nor was there a family history of cardiac disease. Naeem was young and in good health. There was absolutely no explanation for what the cardiologist proclaimed to be a major heart attack.

“A few days ago, I saw a patient with a heart attack like this,” he said. “She’d been in an argument with her husband at the time.” And then he paused as if we, too, might reveal such circumstances.

“You’ve likely had a heart attack,” Dr. Chen said. “You must see a cardiologist.” “When?” “Now.” I ran a red light on W. Genesee an hour later (and a month too late) on the way to the cardiologist’s office.

The steady whoosh-ing of Naeem’s heartbeat should have reassured me that he was all right now, but it did not. I knew what I had seen. Captured by the wand, lying at the cardiologist’s fingertips, present in black and grays, shifting shape ever so slightly with each pulse, was the shadow of death. The cardiologist looked at me for the first time.

“He’s not dead,” he said.

We took Erie Boulevard home, slicing through the Steel Belt city on what had been an artery of the Erie Canal. The late afternoon was a familiar gray; this time the color suffocated like a fog, as if the shadow on the screen had followed us outside, slipped into our car, and was accompanying us home.

I called my parents with the news.

My mother was speechless.

My father asked, “Do you want me to come?”

“Now?” I quickly replied, as if my father’s offer might disappear.

“Heart attack?” my mother asked before we said goodbye. “Are you sure?”

When my father arrived from Pakistan the following month, and stayed almost a week, I realized that I’d never in my whole life spent that much time alone with him. We sat in the living room of our Solvay apartment and watched Wimbledon for hours each day. Martina Navratilova won and won, and Stefan Edberg beat Boris Becker in a five-set match.

For that week, things were as they should be. Wimbledon had been part of my childhood, a family pastime no matter where we were in the world. One summer weekend in 1975, we’d escaped to Murree and instead of hiking, we spent it listening to the voices of British radio announcers compete with static on my father’s shortwave. Arthur Ashe beat Jimmy Connors for the championship and my parents, walking the radio from corner to corner of the room in search of better reception, whooped with joy. Arthur Ashe was black, my mother was white, my father was brown, and no one needed to explain the joy of the moment to my siblings and me.

That winter, when Naeem’s resting heart rate was thirty, only a few beats less than his age, we flew home to be with our parents. There, in Islamabad, my father suggested Naeem see a cardiologist, as if a Pakistani might have better luck bringing his heart muscle back to life. Naeem underwent a thallium stress test to assess the damage. After being injected with the radioisotope and riding a stationary bike, Naeem waited.

The steady whoosh-ing of Naeem’s heartbeat should have reassured me that he was all right now, but it did not. I knew what I had seen. Captured by the wand, lying at the cardiologist’s fingertips, present in black and grays, shifting shape ever so slightly with each pulse, was the shadow of death.

The young doctor tried to be gentle in the face of discouraging films, but by then the diagnosis was old. Eventually, we discussed Denver and the Rocky Mountains, and in an aside, he instructed Naeem not to run in airports, which I recall each time we’re in one. Finally, he asked, “Do you have children?”

“Not yet,” I answered, to which he looked at both of us and softly replied, “It would be the best thing for you.”

I might have been embarrassed at the intrusion, but there was nothing more intimate than watching Naeem’s saggy heart pump slowly on the screen and hearing the doctor describe it as dead.

Years later, when I tell Ayesha about this conversation while we eat carrot cake in a London restaurant, she will laugh so hard the waiter brings us extra water to make her stop. “In Pakistan,” she finally says with tears streaming down her face, “there’s absolutely nothing that a marriage or baby can’t fix.”

Sorayya, what is it about terrifying medical crises that catapult us into an examination of everything else in our lives from relationships to fundamental questions of identity? Is it the complete and utter loss of control over our bodies, that life can be snuffed out like a candle in a nanosecond? You have written magnificently about such moments in your life with your husband and I, for one, felt every heartbeat. Thank you for that, and to Sari for bringing it to us.

Thank you, Sorayya Khan, for writing. And thank you, Sari, for publishing!