Writing for My Life

"Writing renders our world and ourselves. It has saved me more than once." Sorayya Khan considers the creative practice that helps her make sense of life’s impermanence.

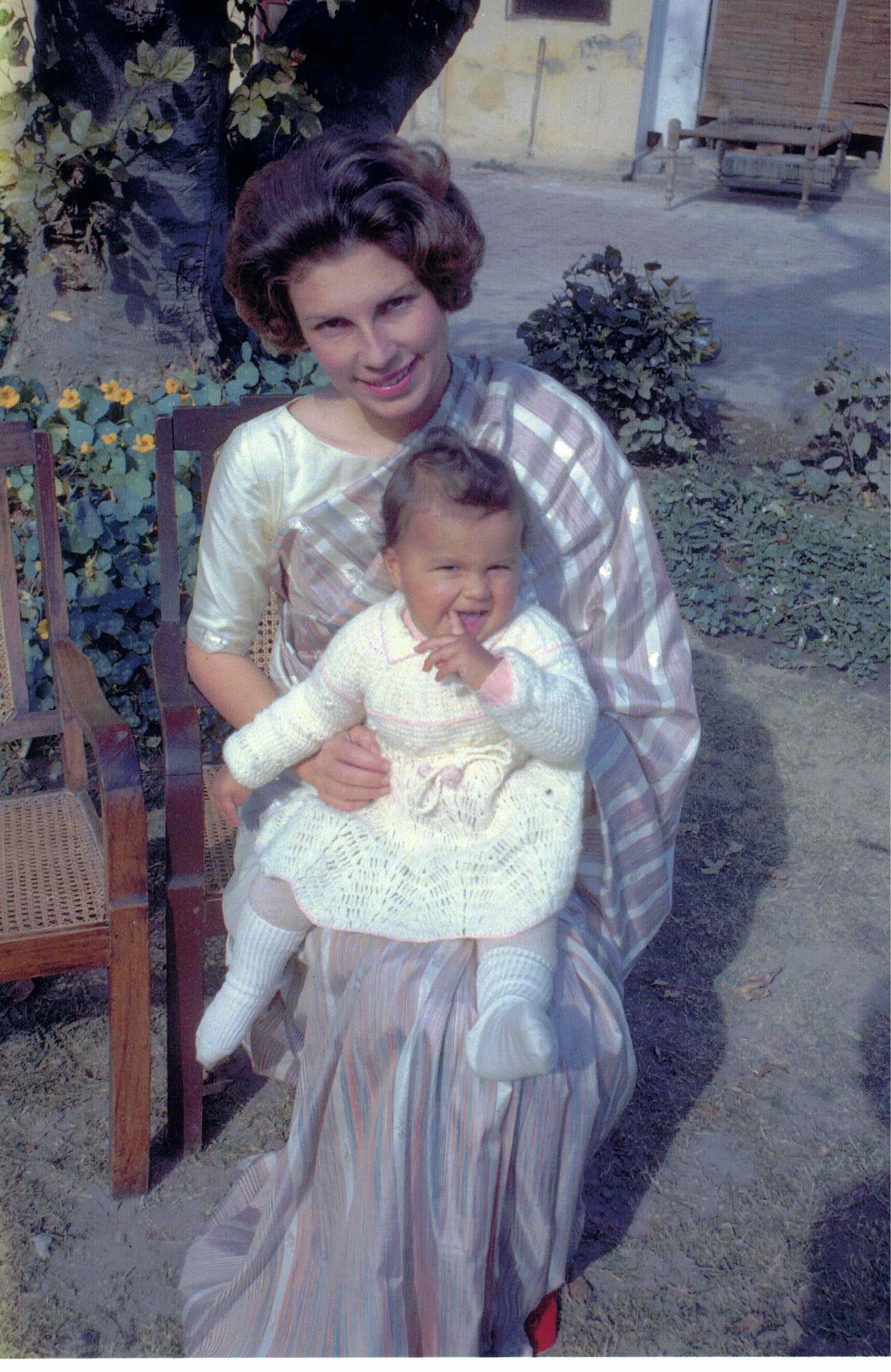

I was 10 that sunny morning at the Islamabad Club. My tall mother bent over in the locker room to slip off her one-piece bathing suit and her belly hung ever so slightly away from her slim frame. She was 38 and I resolved that my stomach would always be flat.

I was 17 when I experienced my first real death, and it belonged to a whole country. Pakistan’s Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was hanged early one April morning. A noose was tied around his neck and the hangman pulled a lever, and for years afterwards I would picture the scene in Rawalpindi District Jail.

At 27, my 63-year-old father told me that he had ten years left to live. I hadn’t imagined that my father’s life would run out, believing he’d always be standing there in winter, in a gold Cashmere sweater, in our home on Street 19, Islamabad, when I needed him. He said it gently, as if he was sorry to know something the rest of us did not. I didn’t believe I was a writer yet, but I made a note of it.

At 27, my 63-year-old father told me that he had ten years left to live. I hadn’t imagined that my father’s life would run out, believing he’d always be standing there in winter, in a gold Cashmere sweater, in our home on Street 19, Islamabad, when I needed him.

In Syracuse a few years later, my 33-year-old husband had a major heart attack that was undiagnosed for an interminable month. Eventually, an echocardiogram revealed the mass of heart muscle that had died. Caught off guard, the cardiologist asked, “Cocaine?” as if it were to blame, but that wasn’t the case. From far away, and over the telephone, my mother said, “Are you sure?” Naeem awoke each morning to a ritual of making faces, in order to begin our day with laughter. I wrote, and we concentrated on living.

I had two young children in my 30s, and who has time to think of death—or anything—when diapers need changing and children need loving? But there it was, my father dying in Vienna ten years after saying he would, catching me by surprise. His death was immense and shocking, but it was also a warning. You may assume you have life left to live (a trip to Morocco, in fact), when it slips out of the body your wife and children will put on an airplane to take to Lahore to bury next to your parents and brothers. For the next year, I researched the novel I was writing as if my life depended upon it.

I had two young children in my 30s, and who has time to think of death—or anything—when diapers need changing and children need loving? But there it was, my father dying in Vienna ten years after saying he would, catching me by surprise.

In my 40s, a friend lost her sister to breast cancer. One afternoon we met in a poorly heated Ithaca coffee shop. Over a cup of tea, my friend asked, “How old are you, anyway?” When I answered, she told me it would be a few years before I wondered how many years I had left. She was right, but I thought plenty about death, my characters’, in the two novels that I wrote in that decade of my life.

My hair started to go gray, and it was amusing at first. A streak down one side, strands here and there. Then it wasn’t so funny and I colored my hair, a lighter brown, a darker brown. While the color hid the gray, I could never escape feeling that it also hid me. One day, after a long day of typing that left my hands aching, I turned to the internet for medical advice. I found an article which linked joint pain and hair dyes, and I decided not to dye my hair for six months. Six months later, the pain in my hands persisted, but my need for dye had vanished. I’m still surprised at the older woman’s reflection in my mirror.

I’m 60 now. I have stretch marks to match my mother’s. Raised veins run like railroad crossings on the backs of my hands, although I wish they didn’t. My hair is grayer. Of course, now I wonder how much time I have left, whether it is the ten years my father knew he had.

Then my mother died. She was 82 and I was 54. Questions arrived in shiny clarity the minute that she stopped breathing, as if they’d been gathering, waiting all along: Was I still a daughter? Half-Dutch? How old was she when she met my father? Time came to a full stop. For months, I couldn’t read. Or write. Words bounced up and down on the page, as if like me, they were searching for a new way to be. Our children were grown by then, the house was quiet. I sat at my desk every day. One day, I wrote a word. Months later, I’d composed a paragraph.

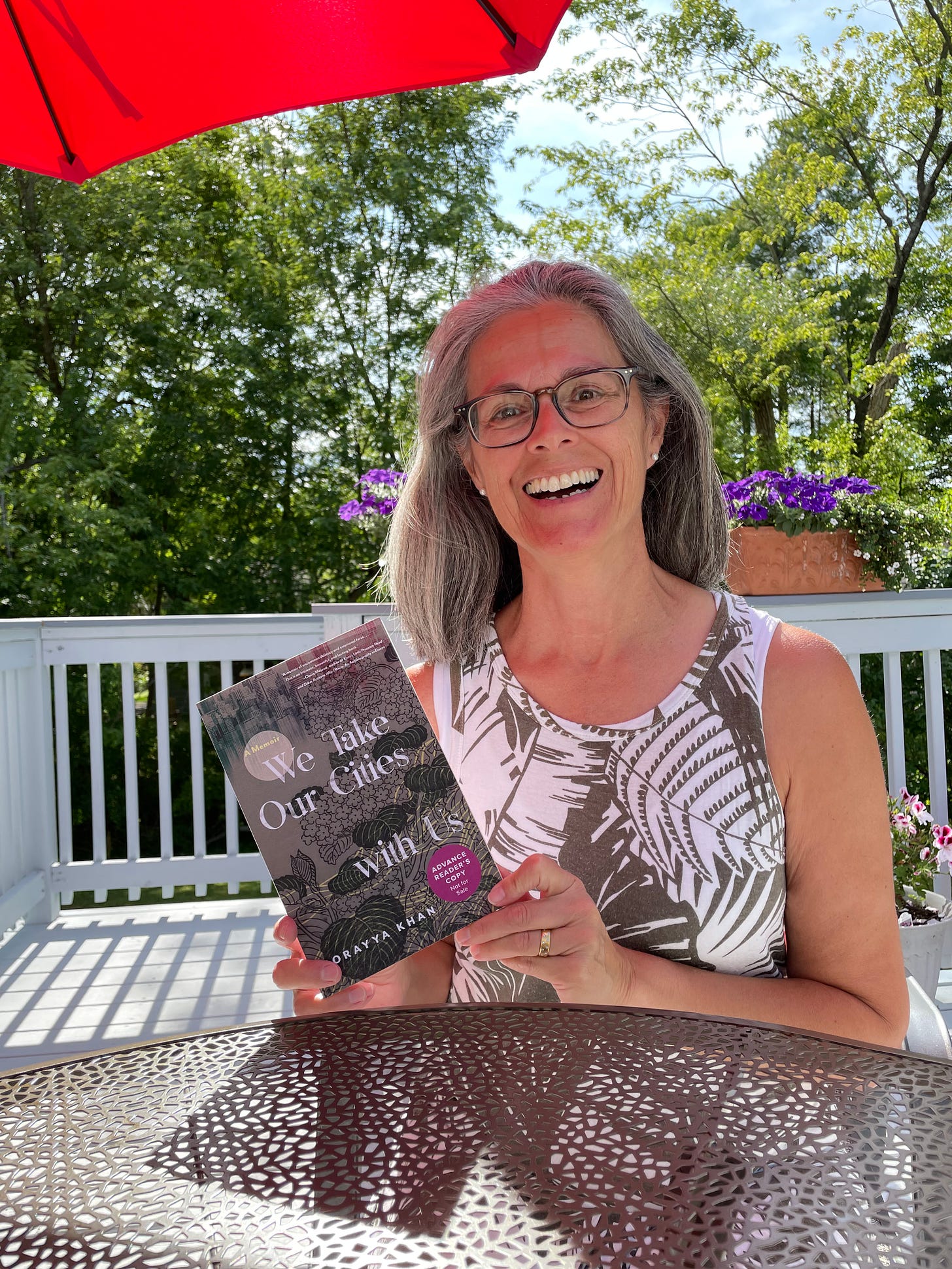

I’m 60 now. I have stretch marks to match my mother’s. Raised veins run like railroad crossings on the backs of my hands, although I wish they didn’t. My hair is grayer. Of course, now I wonder how much time I have left, whether it is the ten years my father knew he had. But I worry less about the years than the novels I need to write, like the one that began to take shape while I revised my memoir, We Take Our Cities with Us, now making its way into the world.

Writing renders our world and ourselves. It has saved me more than once. It puts pieces of me back together and holds me in place. Years pass, decades too, but writing is my constant, like hope and life.

Goodness, what beautiful writing. And how hope-inducing your words are! I’m 52 and working on my first memoir. Ordering your book today. Congratulations!

What an amazing life you have led -- I look forward to reading your memoir!

PS. As a very nerdy word lover, I am curious as to your choice of "render," as in "writing renders our world and ourselves." I had to look it up, of course, and now I'm hoping you'll tell me/us which of the many possible meanings you had in mind. I like this entry:

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/render