Beaches

As he sells the Jersey Shore cottage he shared with his late wife Fran, Irwin Epstein recalls their time together there, and the mutual love of surf and sand that drew them to the place.

More than two years after my wife, Fran, died of cancer, I put our Ocean Grove, New Jersey beach house on the market. I’d thought I could keep it—and with it, maybe a piece of her. I tried. I really did. But at 87, and after two years as a widower, I’ve come around to understanding—and accepting—certain realities.

***

We bought the house together twenty-three years ago, after first renting. After spending a July in Greece, we spent our first August in Ocean Grove. We’d learned about the town from a New York Times article extolling its absence of crowds and overall quietness. No New York City sirens, car horns, or boom-boxes. All you heard before nodding off to sleep were crickets and the lonesome wail of the 11:28 New Jersey Transit train approaching or leaving the next town, Asbury Park, where people came to party and tourists came to drink at the Stone Pony and talk about Springsteen. (Ocean Grove doesn’t even have its own station.)

The town comes by its quietness by way of its standing as a Methodist community and religious retreat, with St. Paul’s Ocean Grove Church at the center of it. Because of that it’s a “dry” town, with no bars, and no alcohol served in restaurants, although a few will let you bring your own. Being church-centric, it unsurprisingly has a lot of rules. Like, no one is allowed on the beach on Sunday mornings, when they prefer residents worship. (That rule is currently being contested in the courts.) And of course there’s no skinny-dipping. (Where would you pin your beach badge anyway?)

Despite its assorted prohibitions, after renting that first month we were surprised to find we hated leaving that quaint little town more than we’d hated leaving Thassos at the end of that July. We couldn’t wait to go back, and it was easy. No passports or planes were necessary; this bit of paradise was only a bus ride away from the Port Authority terminal in Manhattan, where we spent the majority of our time. Adjoining state, beautiful beach, same Atlantic, but very different community than any place we’d ever been.

Despite not being Methodist (instead, a couple of New York Jews), we instantly fell in love with the place, and decided to buy there.

***

Ocean Grove wasn’t our first beach. Much of our courtship had taken place on Fire Island—same ocean, different shores. We’d both always been beach-lovers, starting with Jones Beach, which we’d come to independently.

We’d learned about Ocean Grove from a New York Times article extolling its absence of crowds and overall quietness. No New York City sirens, car horns, or boom-boxes. All you heard before nodding off to sleep were crickets and the lonesome wail of the 11:28 New Jersey Transit train approaching or leaving the next town, Asbury Park, where people came to party and tourists came to drink at the Stone Pony and talk about Springsteen.

As girl-crazy adolescents, my lifelong best friend Jerry and I went to “Jones’s” with his working-class, Italian family. We frequented the part of the beach near Parking Field #1. There, we body-surfed (and body-ogled) and stuffed our pimpled faces with his Mom’s eggplant “sangwitches.” We swam and ate to our heart’s content.

Unknown to me until decades later, Fran and her first husband Stan had also spent much of their courtship on Jones Beach, although in a different area, near Parking Field #6, where he was a handsome Jewish lifeguard and a medical student.

Both jocks, Fran and Stan, and his doctor/lifeguard buddies, played touch football when not rescuing swimmers. As a girl, Fran was a competitive diver. At Columbia, Stan was a wrestler. Stan taught Fran to throw a perfect football spiral—a skill she never forgot. From her mother’s perspective Fran hit the trifecta. Stan’s wanted her son to find someone more feminine. Sadly for Fran and Stan, the thrill of victory didn’t last, and they divorced.

Ocean Grove wasn’t our first beach. Much of our courtship had taken place on Fire Island—same ocean, different shores. We’d both always been beach-lovers, starting with Jones Beach, which we’d come to independently.

Decades later, Fran and I, both single parents with teenage children, met and fell in love at Mt Sinai hospital. She was a social worker. I was a social work research consultant—a Ph.D. sociologist but not a “real doctor.”

Once we were together, for a few years we shared a Fire Island summer house with a fabulously diverse foursome of Fran’s friends.

***

Happy together, Fran and I decided to marry. Not a beach wedding. Instead, we booked Cal’s, an eponymous bistro in the West 20’s for our family-only wedding, officiated by a woman rabbi, under a portable chuppah near the kitchen. Cal provided us, our relatives and our many invited friends with a decidedly non-kosher French buffet reception in his red-leather-boothed boîte. We hired a band of seasoned Black jazz musicians to promote dancing.

I wrote out the deposit checks. Taken together, they were less than our Fire-Island damage deposits. They were an investment in Fran’s and my future happiness for every season of every year we were lucky enough to enjoy together. Thirty-two, to be exact.

Wedding planning completed and deposits deposited, Fran, her teenaged daughter Molly, and I took the jitney from East 68th St to the Fire Island Ferry to announce our wedding plans to our summer housemates, and ensure that they locked in the November date.

Then Fran, Molly and I headed to the beach and came close to ending our lives together in tragedy. The surf was up, the life-guards gone, and Fran suggested a celebratory swim. She was excellent swimmer—on one of her vacations with Stan, the two of them got certified as deep-water scuba divers. The ocean was her playground. She urged Molly and me to join her. Molly did, I didn’t. To this one-time body-surfer, the waves looked too formidable.

A short time later, from the sand on which we’d once or twice even made love, I realized Fran and Molly were in deep trouble. Clearly they were caught in a riptide and heading back in the direction of New York City, minus the jitney. What I didn’t know. and was glad I didn’t, was that Molly was so scared, she began having an asthma attack. With no one to call, iPhones years away from being invented, and the life-guards off-duty, I watched with my heart in my throat, wondering what to do.

Ten long minutes later, they emerged hundreds of feet from where they’d entered the water. Molly was coughing and wheezing. Fran, though, declared it an “adventcha.” Cool in the crisis, she remembered to swim parallel to the shoreline, calmed Molly down, and popped up laughing. Over years, I came to learn that’s the way Fran dealt with every challenge—even cancer.

Two years after we married, with Molly entering college, Fran and I decided it was time for us to do the responsible thing: invest in long-term care insurance. It required routine physicals. Fran was the picture of health. We scheduled and kept our appointments. Then her general practitioner called. Probably a mistake at the lab. For Fran, another round of blood tests.

Our wedding was more like New Orleans than New York City on that brisk sunny Sunday afternoon. Cal spared none of his own expense on spectacular flower arrangements. Recently divorced and often quite dour, Cal seemed as happy as we were. His own abstract paintings and freshly-shined mirrors were everywhere. Terrific food, open bar. The sign on the door said, “Restaurant closed for wedding.”

The only hitch? On advice from his cardiologist, our octogenarian band-leader never once played his well-worn trumpet. Still, he smiled jovially and kept great time. It was such fun.

***

Two years after we married, with Molly entering college, Fran and I decided it was time for us to do the responsible thing: invest in long-term care insurance. It required routine physicals. Already in my 50’s, I was concerned about my slight heart murmur that some doctors noticed and others didn’t. Fran was the picture of health. We scheduled and kept our appointments.

Then her general practitioner called. Probably a mistake at the lab. For Fran, another round of blood tests.

A week later, Fran was diagnosed with Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. We were in shock, but we couldn’t remain in that state for long. We had to act fast. Fran needed to find a donor for a life-altering, and potentially fatal, bone marrow transplant.

To our great good fortune, Fran’s fraternal twin Harriet was a perfect donor match. She was unhesitating in her desire to put up with the pain and risk of bone-marrow extraction to save her sister’s life. A fraternal twin is the ideal donor. An identical twin is the worst. Genetics. Think about it.

But a bone marrow transplant is no walk on the beach. Fran almost died twice during the agonizing process of having her immune system destroyed by full-body radiation and then regenerated by Harriet’s transplanted bone marrow. Much of this took place with Fran isolated in a sterile Laminar Airflow Room, into which rubber gloves inserted through the windowed wall allowed for various medical procedures to be done without anyone entering the space. Otherwise it meant dressing as if for a moon-landing.

Five uncertain years later, Fran was told she was “cured” and that she’d never have to think of Chronic Myeloid Leukemia again. Doctors don’t say “cured” anymore, and we came to learn why: Years later, she relapsed. Before she died, Fran had three more serious encounters with cancer. I had one. She was more anxious about mine than about hers.

While she suffered greatly, Fran busied herself taking pictures of staff and visitors through her window with her sterilized Nikon. She was an avid amateur photographer.

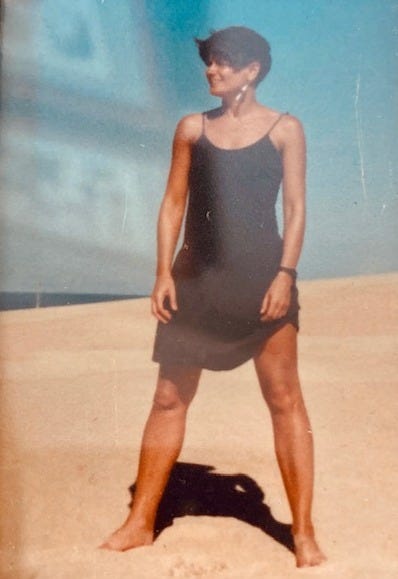

As Fran gained strength from the transplant, we tired of the uncertainty, stress, lack of privacy, and indignities of trying to find a summer rental on Fire Island. We began traveling abroad. We bought and enjoyed a time-share in Mexico, took barge canal trips in England and France. With friends old and new, we spent summers sampling different Greek Islands, and alone finding coves where we could swim nude together.

Five uncertain years later, Fran was told she was “cured” and that she’d never have to think of Chronic Myeloid Leukemia again. Doctors don’t say “cured” anymore, and we came to learn why: Years later, she relapsed.

Before she died, Fran had three more serious encounters with cancer. I had one. She was more anxious about mine than about hers.

***

Fran and I shared our Ocean Grove cottage for two decades. In good times it was pure joy. In bad times, our refuge. We had plenty of both. Instead of Delphi, Ocean Grove became our umbilicus. It always drew us back. It nourished us, centered us, for twenty years.

We most loved the early mornings on the beach before 9, and evenings after 5—before the lifeguards arrived, and after they left. Mornings, on weekdays especially, the beach was empty and quiet—just sun, surf and seagulls. I would pick up a seeded buttered roll, a jelly donut, and two coffees from the local bakery. Fran would head for the beach and set up the umbrella and chairs. Our breakfasts on the beach were equidistant between the bakery and our beach house. But first, we took cool morning swims. It felt like Greece. Only the coffee was weaker.

Fran and I shared our Ocean Grove cottage for two decades. In good times it was pure joy. In bad times, our refuge. We had plenty of both. Instead of Delphi, Ocean Grove became our umbilicus. It always drew us back. It nourished us, centered us, for twenty years.

Afternoons, once the lifeguards were gone, the light softened as the sun got ready to set. That’s when Fran shot pictures. Large, extended Black and Hispanic families arrived with kids and grandparents to beat the beach fees. There were also a surprising number of Russian and Chinese speakers. It was our favorite place to be.

***

Shortly after Fran died, I did the hardest thing I’ve ever had to do: One gray morning before the lifeguards came, as I’d promised her, I swam out to return her ashes to her playground, the ocean.

Then, for reasons I couldn’t understand—perhaps I was in shock—I started making improvements on our house: a backyard pergola, new ceiling fans, a skylight. I imagined Fran lying on the couch all day taking pictures of cloud formations and the wind-blown trees in various seasons. As if imagining could make it so.

It took two summers for me to realize that nothing I did would bring her back, and that as much as I loved the house, and the town, I couldn’t be happy there without her.

Now I’m selling the house with the same broker who’d sold it to us. It feels good to pass it on to someone who shares Fran’s love-at-first-sight—someone who exclaimed, “We’ll take it!” the way she had, before I could say, “Fran, that’s not how you buy a house.”

Thanks to those who noticed and mentioned the typo. I apologize. (I'm doing a lot.) I have fixed it.

I really appreciated how Irwin swung back and forth between the past and the more recent past and the present. I'd dare to suggest that the cottage may be sold but it will never be gone from the Irwin and Fran special story.