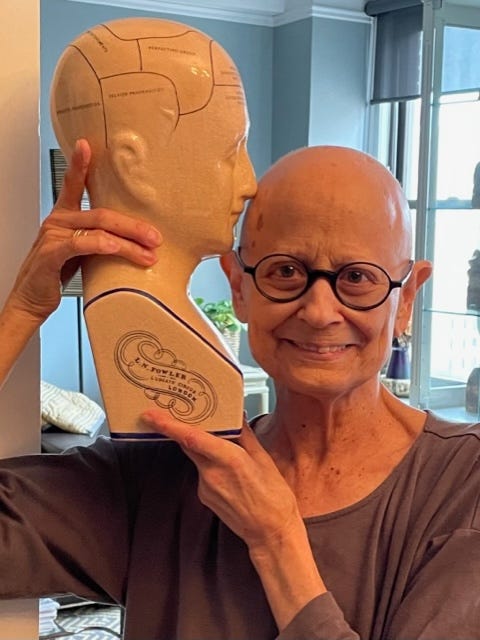

In Memoriam: Remembering Frances Levine Epstein, 1945-2023

This is 85 without Fran. The firsts are the hardest…

Let me start with who my incredible wife Fran was before cancer, which in June took her life.

Everyone who met Fran fell in love immediately. I was not an exception, but I was the lucky guy she said “yes” to.

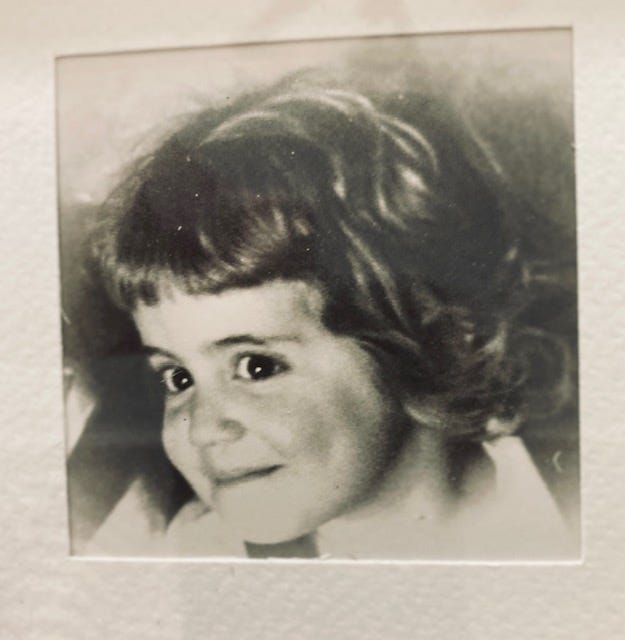

From the start, Fran was all about fun, from the first a playful scamp. That’s the way she always wanted it, seeking enjoyment and knowledge about everything she could possibly know and every human with whom she could possibly connect. In so doing she dared everyone she touched to do the same.

Everyone who met Fran fell in love immediately. I was not an exception, but I was the lucky guy she said “yes” to.

Always a jock, a former competitive diver, an avid tennis player with a sneaky cross-court forehand, a certified deep-sea scuba diver, she was fearless but not reckless. On the beach, she eagerly waited for guys tossing around a football to over-throw one, so that she could surprise them with a perfect spiral in return.

But she was not just a jock. She was genuinely curious and empathic about other people’s lives, joys, worries, and woes. A social worker—as well as a patient—at Mount Sinai Hospital for decades, often simultaneously, she ran the gamut professionally from working with abused infants, to adolescent incest survivors to men and women living and dying with breast cancer.

Though we traveled the world, we spent summers on the Jersey Shore where our little cottage in Ocean Grove served as a refuge from all manner of health setbacks. We both loved ocean swimming. It cleansed all our hurts and wounds. No matter how cold or rough the water, Fran was always the first one in and the last one out.

***

The cancer imposed itself on our life in 1993, two years into what would become a 32-year marriage. It became an uninvited, ever-present third party in our relationship.

Totally asymptomatic, she was diagnosed during a routine but rare visit to her primary care physician as advised by insurance. We were only in our 50s, but thought it prudent to think about long–term care (LTC) insurance. Though we had each been married before, we knew that this love was the “keeper” and we followed the directions in the LTC insurance guide: Get complete checkups. No problema.

The cancer imposed itself on our life in 1993, two years into what would become a 32-year marriage. It became an uninvited, ever-present third party in our relationship.

In my 40’s, I had been the one with aches and pains. She was, or at least appeared to be, in robust and shimmering good health. My doctor said I was fine—maybe a little high on triglycerides but otherwise an excellent LTC insurance investment. Fran’s guy thought they’d made a mistake at the lab.

After re-testing her, a chirpy young hematologist announced that shockingly, there’d been no mistake. Fran had chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). All that was required to save her life was finding a donor for a bone marrow transplant.

We had just dropped Fran’s daughter Molly at Brown University and were looking forward to being able to run around our Upper West Side apartment naked together. That was completely within “Co-op House Rules,” as long as we didn’t run into the halls or use the elevator.

A week after we found out, our first parents’ weekend at Brown involved telling Molly the news. Fran was so panicked that she might switch from “chronic” to the fatal “blast phase” over that weekend that I pulled into a laundromat with a payphone to ask a social work friend at Mt Sinai Hospital, if she knew a hematologist Fran could talk to. By no chance at all, by that time, Fran knew enough about the chirpy one’s life to know they both loved skiing, and while we were at Brown, her hematologist was taking a long weekend skiing somewhere there was snow—maybe Vermont?

We survived the weekend, largely on Fran’s charm, her interest in Molly’s roommates, pleasant if slightly awkward dinners with them and their families, and her curiosity about the norms of the co-ed bathrooms in the dorms. Probably in the reverse order.

Weeks later, we were relieved to discover that by one chance in four, Fran’s fraternal twin sister Harriet was a perfect match on all factors required for a bone marrow transplant; lucky, especially considering that her other sister Carol turned out to be a match on none.

On Molly’s Christmas break and my daughter Bec’s break from pastry-making school, we accompanied Fran to Mount Sinai admissions. Please don’t call it the “beginning of a journey.” For neither Fran nor me was it a journey.

After full-body radiation that destroyed her immune system, Fran spent three months in sterile isolation in a laminar air-flow room “bubble” and listened to a friend’s jazz piano play deck while the transplant took place. Though she almost died twice in the recovery process, we considered ourselves so lucky. A 3-year-old in the next room who received a “Hail Mary” transplant from his identical twin brother died during that time.

On Molly’s Christmas break and my daughter Bec’s break from pastry-making school, we accompanied Fran to Mount Sinai admissions. Please don’t call it the “beginning of a journey.” For neither Fran nor me was it a journey.

Recovery wasn’t easy, and it took a year or two for Fran to resume cross-country skiing again in Central Park with the first major snowfall.

When she crossed the requisite five-year recovery line, the doctor who’d performed the bone marrow transplant told her she should consider herself cured; forget about that worst year of her life and resume life as before. But three years later, we learned again by chance, that Fran had relapsed. While in the hospital, she had befriended yet another hematologist with whom she remained in contact. Fran looked and felt so well, that this third hematologist was curious about whether that meant her immune system was now completely Frans or her sister Harriet’s. Fran thought it would be fun to find out.

That night while Fran was out to dinner with one of her pals, I got the call saying “No emergency,” but Fran should return the call on her cell phone whenever she returned home. At 11 pm, after two hours of silence and dread, Fran bounced in, tipsy on life and I gave her the message. She called immediately to discover she had relapsed. Her chronic myeloid leukemia had returned.

By then, a chemo drug called Gleevec was the new “no-brainer.” Invented for an entirely different disease, despite side effects, Gleevec brought Fran gradually into a good enough remission to return to our lives again. Again, we counted ourselves lucky.

Then followed breast cancer to which Fran sacrificed a breast. She underwent more radiation, and another five years later she crossed the statistical finish line so that she no longer required daily medication. By that time she had befriended her oncologist sufficiently to learn that he was receiving treatment for some form of brain cancer. She was devastated. He loved talking to her but had to retire. They would miss each other.

Now let me tell you who Fran was, who she continued to be, throughout her battle with cancer. Throughout, she never asked, “Why me?” Instead, even when disappointing scan results arrived, she asked, “What’s next?”

Our luck started running out completely in 2015 when Fran was diagnosed with late-stage upper-track urothelial cancer on return from a trip to Hong Kong to celebrate my retirement from academia. With her usual optimism, she contributed a kidney to this unwelcome guest six years ago, and ultimately her life, just a few months ago. But, if it can be believed, for almost all that time, we shared an extraordinarily happy life full of meaningful work, travel, friends, family and fun.

***

Now let me tell you who Fran was, who she continued to be, throughout her battle with cancer. Throughout, she never asked, “Why me?” Instead, even when disappointing scan results arrived, she asked, “What’s next?”

No matter how sick she was, Fran remained incredibly generous and kind to others. As one grieving friend recently put it, “No one listened like Fran.” An art therapist who spent time with her during several hospitalizations and outpatient chemo sessions said she always felt guilty when the session ended, because she thought she’d gotten more from it than Fran. And she insisted on “keeping it real.” A long-time beneficiary and simultaneous sufferer of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), she got her oncology team psychiatrist to admit he, too, had ADHD as well, since he was often as late for appointments as she was. She urged him to work on his time-management skills.

Once, when her new and very sensitive urological oncologist was giving her bad news about her latest scan results, she interrupted him, touched his arm gently and remarked soulfully, “And you have to do this every day?” His head fell a bit as he allowed, “It’s not the best part of my day.”

No matter how sick she was, Fran remained incredibly generous and kind to others. As one grieving friend recently put it, “No one listened like Fran.”

Fran loved life—our life—and was up for anything that might give her more of it. She talked a good game about “quality of life,” but it was life and life itself that she wanted, and fiercely insisted upon. Over the course of years and until the end, when disappointing cancer news came in, she would ask about new meds in the pipeline. The answer she repeatedly received was, “There’s always something else,” and her response always was, “Let’s go for it.” Until there were no more meds to try.

***

The last time, trying an “off-label” med (i.e., not officially FDA-approved for her cancer but offering some legitimate ameliorative possibility along with a whopping co-pay) she suffered so from side effects that her oncologist said for the first time, “there’s no point in continuing treatment.”

She was, for the first, time crushed, and wanted at least another two months and scans. But looking at her and her obvious signs of suffering, the doctor said no. Witnessing her acute suffering myself, I was relieved he said it, but conflicted about my relief.

Fran’s response reminded me of boxers I’d watched on Friday Night Fights with my father as a kid. In the final round of a championship fight, some palooka was pummeled from pillar to post, until his manager threw in the towel. The bloodied but unbowed fighter would inevitably protest that if he could just finish the round, he could knock the opposing bum out.

Like that hapless but still dangerously hopeful fighter, Fran was angry. Couldn’t she at least have more scans to see how much her cancer had grown over the past month? Her oncologist’s response was she could, but what would be the point? She said she was “just curious, that’s all.” But reluctantly, again to my relief, she finally agreed; it made no sense.

Once, when her new and very sensitive urological oncologist was giving her bad news about her latest scan results, she interrupted him, touched his arm gently and remarked soulfully, “And you have to do this every day?” His head fell a bit as he allowed, “It’s not the best part of my day.”

Crestfallen but still not on the canvas, Fran accepted in-home hospice for a month, but never bought into the rosy dream of dying at home, free of pain, with loving relatives gathered around. Regular chats about coming to terms with death with a Mount Sinai Chaplain, a home-hospice rabbi, a zen coach, an end-of-life doula, a Catholic pharmacist, and a Baptist doorman who offered to come to her bedside and pray with her, all made no difference. The rosy dream never materialized. By then, the pain and the metastasis were uncontrollable.

Sitting ringside, I found her agony was my agony. For thirty years I’d known how to comfort her. For that awful last month, I didn’t.

***

Now I face many painful “firsts.” The “firsts” approach like diving WWII Japanese kamikaze planes, unexpected and out of nowhere, dreadful in the pain they can inflict. Now all I seem to have are “the firsts” that everyone who has deeply loved and lost experiences.

The first Wimbledon men’s final alone in thirty-two years, unexpectedly conjuring up Fran positioning herself to the side of the tv, swaying back and forth trying to time the men’s first serves. I thought I’d distract myself by watching, but found I was simultaneously bored and heartbroken, crying through the first set. I thought Djokovic would easily win anyway, and turned it off. I was buoyed to learn later that Alcaraz, won even though I missed a great match. If I’d continued to watch, I would have missed Fran yelling in the background, “Approach the net!” “Down the line!” “Get it, get it!” “Oh no!”

A week later, the exterminator was scheduled to come. Though she loved people, Fran reserved much of her hatred for water bugs—the omnipresent New York apartment pests. Naturally, she loved it when the exterminator came so she could practice her Spanish while telling him where to set his traps. Their conversation would always begin with “Como se dice waterbug?” Then she’d ask about his wife and children. He’d always leave laughing in his mask and shaking his head.

Before she died, I promised that I would return her ashes to the sea, from which we all came. I brought her ashes to Ocean Grove, lamenting that this time she wouldn’t be coming out of the ocean for me to wrap a towel around her again until she stops shivering and smiles at me.

I thought, Oh, my God! How will I tell him? Should I pretend I’m not home? Fran would be furious. So I took a deep breath and opened the door and explained that she’d died. He fought back tears and so did I. I followed him around the apartment for the company but had no strategic suggestions. On leaving he said, “Thirty years? She were skinny, but she were strong!”

I agreed and completely lost it after I closed the door.

Before she died, I promised that I would return her ashes to the sea, from which we all came. I brought her ashes to Ocean Grove, lamenting that this time she wouldn’t be coming out of the ocean for me to wrap a towel around her again until she stops shivering and smiles at me.

A week after I scattered her ashes I learned that our only shade tree in Ocean Grove had to be cut down. It had been struck by lightning during Sandy and yet half survived. It seemed to be flourishing but an arborist said it needed to be taken down. We’d both hoped it would outlive us. How can I say I’m happy that she didn’t see this when I would have wanted to share the grieving with her?

So I had installed a skylight in our living room to bring in the changing light, the sky, the crown of neighbor’s trees. She would have loved it. But it won’t bring her back.

At her funeral service I said her “takeaway” was, “Love your life and love the lives of others.” For me at least, that message remains.

You’re not alone Elissa. I even made my psycho-pharmacologist cry last week.

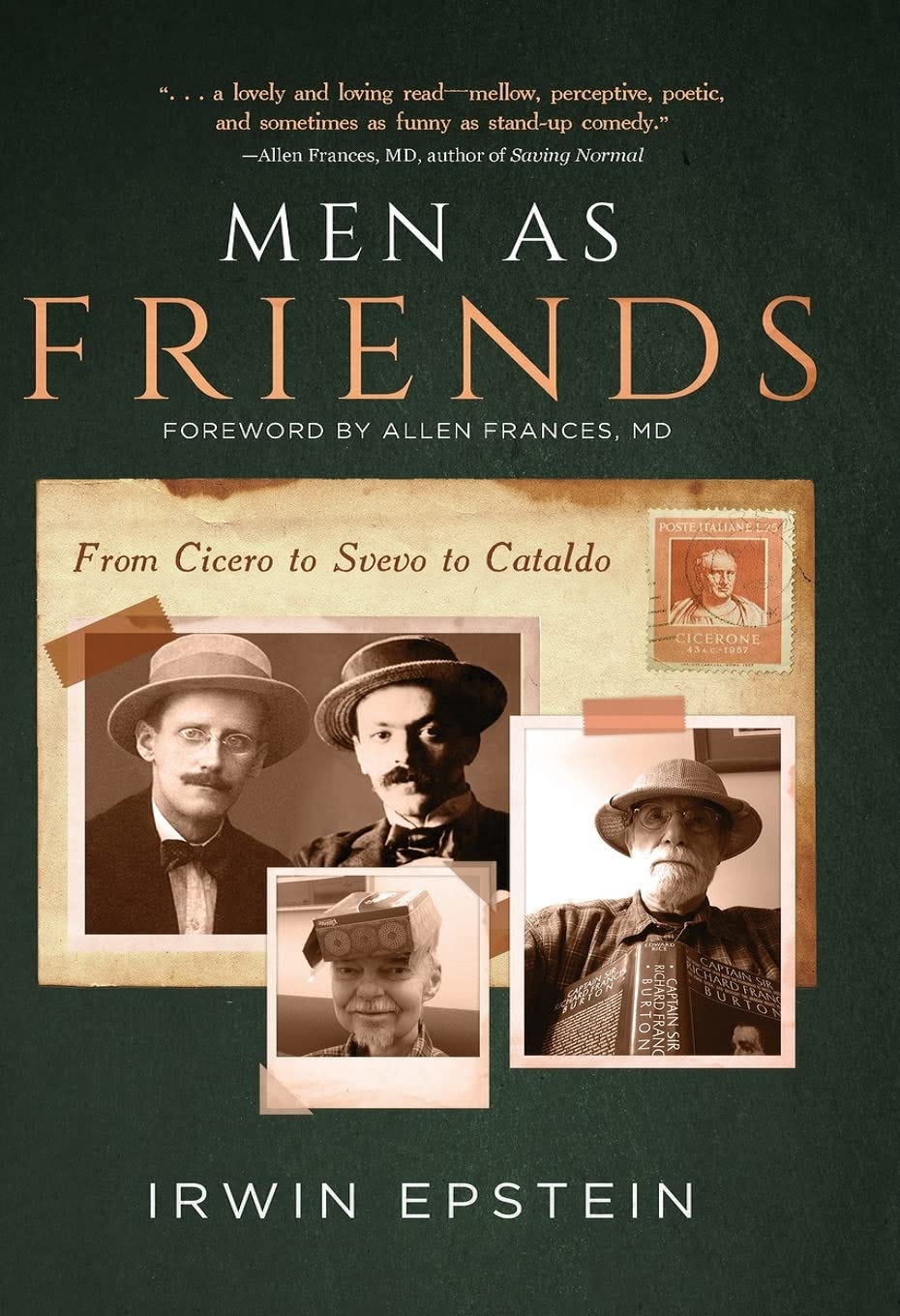

Irwin is just fine Mary Sue. Just don’t call me “Irv”. And hugs are welcome. I just love and have always loved, introducing Fran to others. Never as a trophy. But just because I felt so lucky. I didn’t realize it when I wrote this, but now I see it and am so grateful for the responses like yours. Thank you.