You're Not Supposed to Become a Huge Fan of Black Flag as a Middle-Aged Dad

Losing my job at 48 somehow led me back to the punk rock band I’d failed to embrace in middle school.

Editor’s note: A reminder that in my book, everyone who is alive and aging is considered an Oldster, and that every contributor to this magazine is the oldest they have ever been, which is interesting new territory for them—and interesting to me, the 58-year-old who publishes this.

When you see a piece featuring someone younger than you, try to remember when you were that age, how monumental it felt, how reaching that new age meant considering different choices. Bring some curiosity to reading about how the person being featured is experiencing that age. Or, if you prefer, wait for the next piece featuring someone in your age group. Not every piece will speak to every reader. I’m doing my best to cover a lot of ground and to foster intergenerational conversation. Work with me.

***I will delete any comments that dismiss contributors’ experiences of getting older because they’re allegedly not old enough*** - Sari Botton

There’s an old saying that the older you get, the more you connect with country music. Maybe that’s true, but it certainly seems that the older most people get, the more they mellow out, and the quieter their music becomes. I still see middle-aged dudes at rock shows wearing Dead Kennedys and Agent Orange t-shirts, but those are people who maintained their musical taste through the years. It’s unlikely they first got into punk rock at their age. Strangely, that’s where I found myself. I wasn’t reverting. I wasn’t lapsing into nostalgia, because punk rock wasn’t nostalgic for me. Instead, I was connecting with one of punk’s best bands at a time when my peers were choosing nights in front of the TV overnights at rock shows. This seemed weird and exciting.

***

Moments after I dropped my daughter off at school, my employer laid me off. I hadn’t even had my morning tea when the Microsoft Teams meeting started.

“Good morning, Aaron,” said the head of HR over video.

HR explained my situation with a series of canned phrases: We’ve decided to restructure… internal efficiencies… “tough” decisions. I knew the reason. Clients kept leaving. To slow the bleeding, they’d hired an ambitious, controversial Chief Marketing Officer to rethink seemingly everything, and as she streamlined, staff got cut. This round of layoffs included me and approximately twenty other people.

Today would be our final payday, and our medical, dental, and vision insurance would end then, too. Access to Microsoft Teams and email would terminate 20 minutes after the meeting.

I used my 20 minutes to bid coworkers farewell. Then the apps logged me out. It wasn’t even 9:30 yet.

Loyalty, seniority, quality work—nothing could save me from the axe. Neither could the relationships I thought I’d built at this marketing technology company. Granted, I’d already started looking for a new job, because I’d been eager to pivot away from marketing software to mission-driven environmental work. If I was going to market stuff, I wanted it to be something that mattered, like sustainability or environmental advocacy that benefited humanity, not just a corporate bottom line. Searching for work while working a full-time job as a full-time parent was exhausting, so getting let go released a certain pressure. But it also made me pissed.

Moments after I dropped my daughter off at school, my employer laid me off…I boxed up the computer and signed up for unemployment while blasting Black Flag’s “Nervous Breakdown.” Although I didn’t consider myself a fan of this ’80s punk band, the song’s blazing fast guitar riff was the perfect accompaniment for releasing anger.

For three years, I’d given myself over to this company. They didn’t provide any sick days, only personal time off (PTO), which barely increased over my time there. I got one puny raise despite really throwing myself into my work—I stressed, stayed up late, woke up early to crank out everything from ad campaigns to sales email sequences, and I made their big-money proposals look and sound professional, rather than some ransom note. The CEO even had me ghostwrite many of his companywide emails. He trusted me and my abilities, yet this was how they now treated me.

As I boxed up my work laptop to mail back, I considered decorating it with a hissing possum sticker that included the words “Eat Trash Hail Satan.”

Sometimes when I get mad, it awakens my young punk self. I never dressed as a punk with a mohawk or spikes, but my spirit was punk. Growing up as a skateboarder in the ’80s gave me the uniform and music to use as emblems indicating I was wired for challenging authority and paving my own way. Being punk was about the freedom to create your own identity and do what you wanted to do: publish a zine, form a band, book your own tours. Nirvana singer Kurt Cobain said punk is about “saying, doing, and playing what you want.” I did that as a writer. Unfortunately, too many kids twisted punk ideals to mean a certain kind of music, a costume, and hostility, but the true punk spirit was constructive, not destructive. And yet, telling my employer to fuck off was my adolescent reflex. I wanted the company to know they were callous, so they’d feel some moral accountability. The adult part of me knew that wouldn’t matter. Most importantly, in order for me to get my small severance, I needed to return their equipment intact—and I wanted that money more than I wanted empty “revenge.”

Famous quotes say living well is the best revenge. They say revenge is sweet, but it never satisfies. As attractive as it is to vent anger, vengeance just corrodes you spiritually and psychologically. As Gandhi said, “An eye for an eye will only make the whole world blind.” And as author Richelle E. Goodrich wrote, “A society built upon a foundation of vengeance is a society doomed to destroy itself.” Society was exactly what I was thinking of as I looked for mission-driven work.

So I boxed up the computer and signed up for unemployment while blasting Black Flag’s “Nervous Breakdown.” Although I didn’t consider myself a fan of this ’80s punk band, the song’s blazing fast guitar riff was the perfect accompaniment for releasing anger. It’s one of punk’s most iconic guitar riffs. I didn’t care about the lyrics. To me, they’d always seemed adolescent. I just wanted angry music.

As I filled out unemployment forms, Black Flag singer Keith Morris’s voice pierced through Greg Ginn’s perfect guitar riff:

I hear the same old talk, talk, talk

The same old lines

Don’t do me that today

Yeah, if you know what’s good for you, you’ll get out of my way.

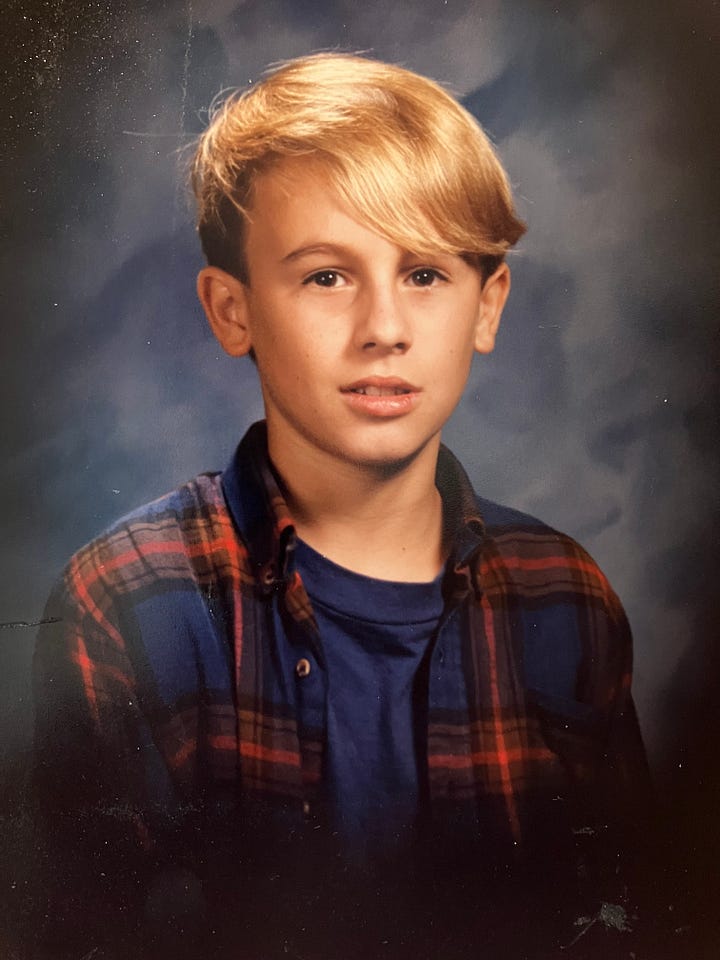

I’d first heard this song in 1986 or ’87, around age 11. Suddenly, at age 48, “same old lines” spoke to me.

As lyrics often do, these now fit the shape of my life. Their vagueness accommodated my sense of victimhood and the vacant cliches HR fed me.

Corporate brands need worker bees to generate revenue. But first, they try to make us feel valued. They use psychological tactics and formal culture-building programs—Kudos Rewards, a book club, free company swag—to convince you that hey, buddy, we’re all part of a team, united in a mission to generate profit, win market share, and crush the competition. This is our culture: innovation, teamwork, community, integrity. I had written the company’s Life pages on LinkedIn. I knew how engineered this kind of internal communication strategy was. In fact, I even wrote a blog post about it! You know: We are a company with a strong community that values creating and maintaining relationships with our colleagues, no matter where they work, because this company is so much more than the technology we design.

All that stuff goes out the window with your insurance as HR hands you your marching orders.

I wasn’t reverting. I wasn’t lapsing into nostalgia, because punk rock wasn’t nostalgic for me. Instead, I was connecting with one of punk’s best bands at a time when my peers were choosing nights in front of the TV overnights at rock shows. This seemed weird and exciting.

Ultimately, at any given company, there are few actual teams. There’s little integrity and cohesion. The only company culture is profit. The people who once acted as if they cared about your kids send you off with empty cliches like, “We wish you the best in your career endeavors.”

Remember:

“This paycheck will be your final paycheck.”

“Your medical, dental, and vision coverage will continue until the end of this day.”

“Your passwords will no longer work in 20 minutes.”

Integrity.

Teamwork.

Community.

Being treated like that, it’s tempting to make them the enemy. You pieces of shit! Choke on Satan’s cock! But that doesn’t feel good either. I wanted to expunge venom, not carry it. So for four straight days, I listened only to Black Flag as a sort of exorcism.

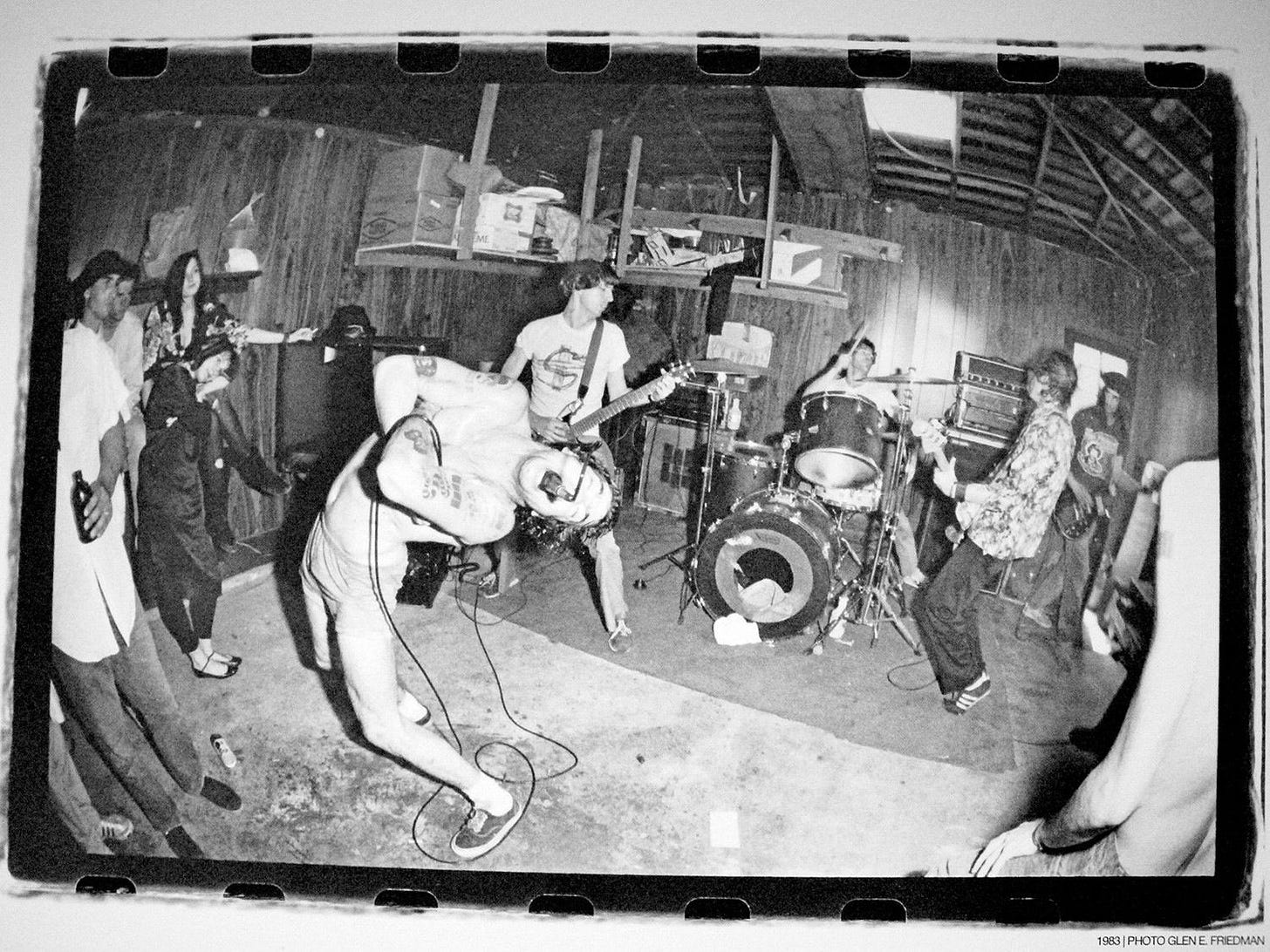

After ripping through “Nervous Breakdown,” I played a Black Flag best-of album featuring some of the band’s canonical songs, including “Rise Above,” “My War,” and “Six Pack.” Simmering in it—the music’s speed, the singer’s screaming—helped me get it all out.

In middle age, I’d found healthy ways to vent that involve exercise, not booze, so I skateboard, bike, and blast music. Before this latest brush with the ills of capitalism, I didn’t expect that would involve Black Flag.

My wife and I had decided to repaint our house ourselves to save money, so I scraped paint and sanded the cedar siding to release my feelings. As I played the best-of album on repeat, Black Flag’s fast songs lost their luster, just as punk rock itself had for me in middle school. So I started playing full albums that I didn’t know. As I dove deeper into Black Flag’s catalog, I fell in love with their music in a way I never had as a young skater.

“Black Coffee,” “The Bars,” and “Paralyzed” enthralled me, and I sang along to new instant favorites like “Bastards in Love” and “I Can See You.” Strangely, that best of record didn’t include a single song off their final studio album, In My Head, or their most innovative EP, I Can See You, which they released after they broke up in 1986. By favoring the obvious fast songs, the compilation’s curator had missed Black Flag’s more avant-garde music and many catchy tunes, which meant that they, like I, had missed the true spirit—the range—of this supposedly “punk” band.

How strange that it took this many decades to finally hear the brilliance of their oddball instrumentals like “Obliteration” and to appreciate Greg Ginn’s dissonant, atonal guitar. It was so infused with jazz. They’d started as punks, but these musicians were so much more. By embracing the punk spirit without the rulebook, they rewrote what rock ‘n’ roll could be. No wonder their later albums angered punks. Fans who only wanted conventional hardcore couldn’t open themselves up to this new music, which was shaped by the Grateful Dead—the hippies!—as much as anything. High up on a ladder, covered with scraped-off lead paint, I found myself grumbling fanboy laments: Why couldn’t they have released more songs like the four on I Can See You? Those were more sophisticated and rewarding than their beloved album Damaged. Why didn’t more people embrace their final album In My Head the way they embraced the exalted My War? Suddenly, I was hooked.

Adulthood had equipped me with the patience and the openness to form judgments of the music not from kneejerk reactions or inherited ideas, the way I had as a kid, but from actually listening to the music. I played it. I let it in. And finally heard it in the unbiased, nuanced way that music deserves.

Better late than never.

* * *

It’s not like they were new to me.

I’d first listened to Black Flag in sixth grade, in 1986 or ’87. As a skateboarder in the 1980s, you listened to bands like Dead Kennedys, Circle Jerks, and Agent Orange. SST Records, run by Greg Ginn, ran ads in Thrasher magazine, but you didn’t need ads. Other kids’ band shirts told you what you needed to know: Black Flag were cool, Megadeath was not.

The thing is, I knew we skaters were supposed to like Black Flag, but the music was too fast. All three of the band’s singers screamed too much. Even as a kid I found some lyrics were too simplistic to sound anything but dumb: “Fix me / Fix my head / Fix me, please, I don’t want to be dead.” Rhyming dead with head? Come on. Other lyrics seemed too dramatic, like “Life’s miseries, pain runs deep / Does it matter that anybody cares? / Can’t there be another outlet?” Punk’s fixation with anger, alienation, and boredom didn’t jive then. I was a prankster, but I didn’t feel alienated and angry, and I didn’t like violence. Punks seemed so violent. So did certain Black Flag album covers, like the one for Family Man, which featured a dead mom and a dad holding a gun to his head.

Being punk was about the freedom to create your own identity and do what you wanted to do: publish a zine, form a band, book your own tours. Nirvana singer Kurt Cobain said punk is about “saying, doing, and playing what you want.” I did that as a writer.

Musically, all punk rock started to sound the same to me by seventh grade. I hadn’t yet found Bad Brains, Minutemen, or Buzzcocks, so my range was limited, but where were the hooks? The melodies? It was all one, two, three, go! Even holy grail bands the Sex Pistols seemed performative and insincere, never mind that so many punk albums had the worst covers. When you compare Subhuman’s covers to Joy Division’s, you see the power of design on consumers. Artforum magazine called the cover of Black Flag’s Damaged “iconic,” but to me, The Smiths’ self-titled 1984 debut looked like art. Damaged looked like a 10-year-old had made it. Then again, the fist in glass on the cover was just the kind of image a teen boy could relate to, and so many punk bands from that era needed enemies. It’s us against the government. It’s us against the suburbanites. Mistakenly, I’d lumped Black Flag in with all the other punk bands, and I spent the next few decades telling myself that I didn’t like them.

There’s a Taoist saying: When the student is ready, the teacher appears. Now that I’d fallen for the Grateful Dead and mid-century jazz, my tastes were expansive enough to see that I actually was a Black Flag fan. I just hadn’t truly known who they were before.

* * *

Through the cathartic tedium of scraping and sanding, hearing Rollins screaming “Anger and coffee, feeding me / Drinking black coffee, black coffee, black coffee, staring at the wall!”—that was therapy. The grinding, repetitive dirge “Sinking” was cathartic: “When I’m feeling it / When I’m down and out / It hurts to be alone.” Pushing deep into their catalog let me finally get my head around this confusing, legendary band.

Black Flag didn’t exist for long, but they stayed busy. They released three albums in 1984 and two in 1985, then they disbanded in 1986.

Damaged and My War are considered their masterpieces. Damaged created hardcore music. My War slowed punk down and paved the way for Grunge. You can’t understate their influence, but when I relistened to them, I still preferred Slip It In and In My Head.

Released in 1984 between tours, Slip It In is a brooding masterpiece that mixes punk and metal. Released the year before they broke up, In My Head is defined by atonal, unusual guitar parts that are more interesting than straight, blazing hardcore guitar lines. It’s pained, innovative, challenging—the sound of a more sophisticated band. But their final EP, I Can See You, blew my mind. Released three years after they broke up, its four songs sounded like nothing else they’d done. As the days passed, I kept wishing they’d written more like this. I also loved the more conventional Loose Nut more than—gulp—Damaged. Sacrilege, I know.

In 1985 Black Flag released the fully instrumental album, The Process of Weeding Out. Completely avant-garde, it sounds more like Sonic Youth than previous Black Flag, which made it an intentional challenge to fans and band members: If you didn’t like this music, then step aside, because this is as much Black Flag as Nervous Breakdown, arguably more.

* * *

With my new free time, I keep searching for work. My family is tightening our belts, but we’ll survive.

I keep trying to move past the idea that success is the best revenge, because revenge is the language of war. One-upmanship traps you in a cycle of conflict, even when dressed as justice. Instead, I want to focus on what I can create: relationships, collaborations, sharing networks, love. Maybe that’s a more mature punk response to corporate callousness? Scraping and painting your house yourself when you’ve never done that before—people call that DIY now, but it’s also the true punk spirit. So is charting your own way in a new nebulous profession. Either way, now when I encounter Black Flag, I feel a connection I’d never before felt.

I keep trying to move past the idea that success is the best revenge, because revenge is the language of war. One-upmanship traps you in a cycle of conflict, even when dressed as justice. Instead, I want to focus on what I can create: relationships, collaborations, sharing networks, love. Maybe that’s a more mature punk response to corporate callousness?

The rock website The Hard Times publishes satirical articles that riff on middle age. A few recent headlines read: “Pragmatic Middle-Aged Guy Only Skates in Urgent Care Parking Lots” and “Poser Still Hasn’t Heard Every Band Yet.” Another joke about the band’s iconic black bar symbol: “15 Black Flag Songs You Need to Know Before You Can Legally Get the Bars Tattoo.” It lists all the obvious songs, like “Rise Above,” and closes with “Fix Me.”

“Congratulations,” The Hard Times writes, “now you can pass yourself off as a real Black Flag fan. If someone tries to talk about how the songs on Loose Nut and Family Man are underrated just ignore them. They are liars or they suffered some sort of head injury.”

I’m that someone talking about Loose Nut and Family Man.

Now I get the joke. Can I get my bars?

My go to song which I play loud enough to make my iPad warn me about hearing damage is The Pixies: “Where is my mind”. Been laid off twice because I was “too gay”! so ‘choke on Satan’s cock’ particularly resonated. Happy to be retired and never going back.

Great read! I started listening to angry music in my mid-50s—bands like Sleaford Mods and Amyl and the Sniffers really resonate now. Still figuring out why, as a 60-year-old, semi-retired, turtleneck-and-fleece-vest-wearing woman living in rural New Hampshire. I drove a 2 hours down to Boston a couple of weeks ago to see Amy Taylor scream and jump nonstop. It was glorious and cathartic.