Seasons

Terry Ratner reflects on the ways two deaths affected her as a nurse, and led her to take the changing of the seasons in stride.

The way I practice nursing might have been different if I hadn’t lost my mother in the spring of l993. The time of year when the nights stay cool and days begin to warm. That’s when I began to bond with little old ladies wearing turquoise rings and glittering beads. I’d laugh with them like old friends and study their faces searching for a connection: hair the color of freshly fallen snow, skin paper-thin, eyes shining like topaz, and a dimple when they smiled.

***

There are two main seasons in Phoenix: summer and winter. Our fall and spring are bypassed for long stretches of sameness. Maybe there’s a hint of spring in March, when a frail rain falls, casting a silver net over the neighborhood. Then the sky clears and the flowers smell like baby lotion until the aroma is suffocated in blazing heat. These are our seasons.

Nursing also has its seasons. They follow no direct weather pattern and occur as suddenly as a hurricane or earthquake, without any warning. There are brief periods of calm with little activity, just the daily comings and goings of patients — the ones who recover without much pain, without any scars.

Nursing also has its seasons. They follow no direct weather pattern and occur as suddenly as a hurricane or earthquake, without any warning. There are brief periods of calm with little activity, just the daily comings and goings of patients — the ones who recover without much pain, without any scars.

Then the changes occur: Trees with still branches begin their dance; the full moon wears an orange veil as winds throw blankets of dust like confetti up toward the sky. In daylight the air fades to sepia, like an old photograph. That’s when code bells chime and intensive care units fill to capacity with dying patients and grieving families. The scent of loss is everywhere, and one can’t escape the inevitable season of death. It begins in the arteries, rushing words without words. Some agree, “It’s too soon for death.” Others welcome the freedom from pain. The season passes by like a series of cold breaths, one after another.

***

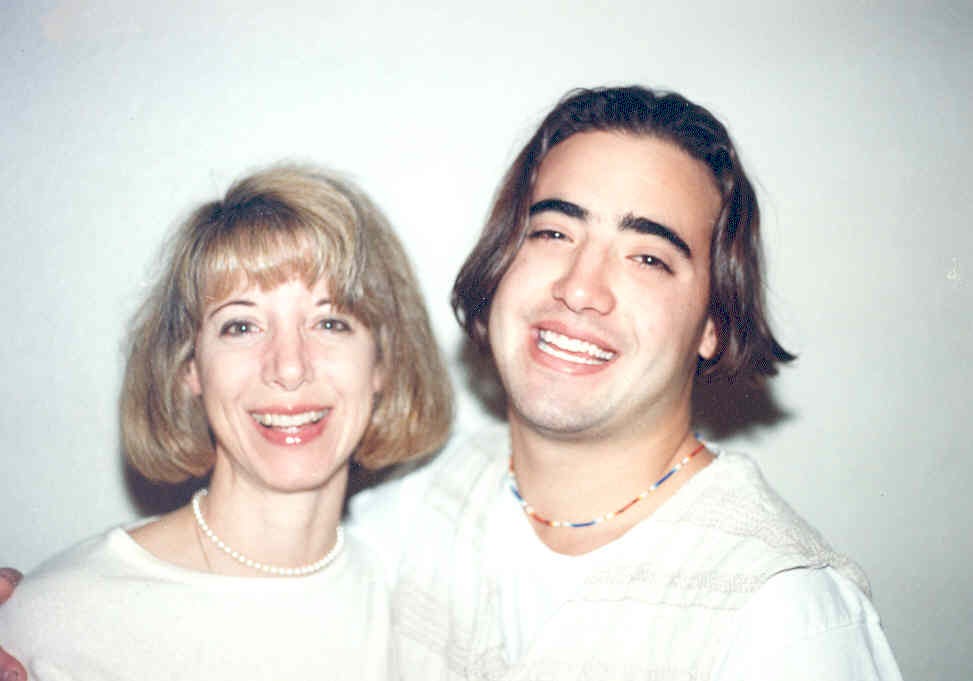

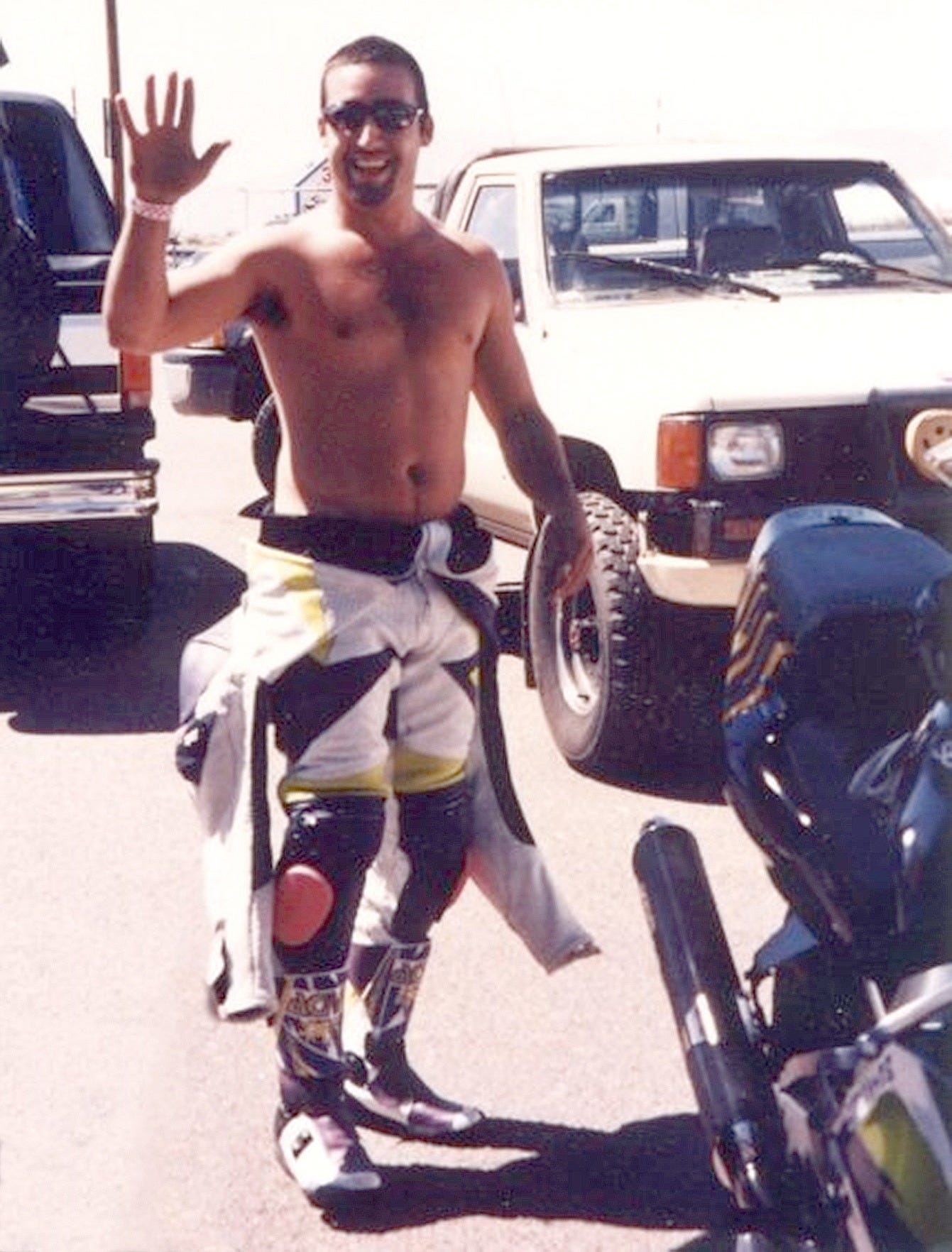

My nursing care changed again in the spring of l999, when my 25-year-old son, Sky, was killed in a motorcycle accident. All the young patients became a part of me — each one taking up a small space in my heart trying to fill the emptiness.

It all happened during the season that’s sometimes missed. During the season that hides; the one that smells like jasmine and sprouts tulips from the darkness of the earth. A season that cools the evening sky with its sweet resinous wind while orange tree petals drift to the ground like snow. The season filled with colors; fairy dusters with pink puffs radiating from their centers and clusters of purple wisteria trailing around budding trees. That’s the season my world caved in.

***

Those two deaths affected my career in ways I never understood until now. They left a sickness in my heart that can’t be healed from medicine. No chemo, drug, or miraculous homeopathic pill can take it away. No narcotic is strong enough to dull the pain.

My nursing care changed again in the spring of l999, when my 25-year-old son, Sky, was killed in a motorcycle accident. All the young patients became a part of me — each one taking up a small space in my heart trying to fill the emptiness.

My patients are the medicine. Ladies with blue hair who want to hold my hand and call me “honey.” The old men with salt and pepper sprinkled on the few hairs they have left tell me a joke because their children are too busy. The young people who are having surgery because they were reckless, the ones I catch myself preaching to — these are the patients who fill my void.

I pre-oped a young man last week. Inside the paisley curtains, he cursed as he shook his head side to side and moaned, sounding like a pop star singing a song of love and loss. “Help me, someone, I can’t take this pain any longer,” he yelled. I pulled a chair close to his bed, placed a cool washcloth across his forehead, and injected morphine into his vein. I asked him how the accident happened. “I was riding my dirt bike out in the desert and got carried away performing. I fractured my left leg.”

I looked at the external fixator attached to his leg, the swelling in his ankle and knee, and the metal pins in his bone. I watched his temple pulsating and thought about life, about luck, about my son, and wondered why he’d had to die.

I took his calloused hand in mine and listened as he talked about the accident. “I don’t know, the bike just got away from me,” he said. The connection between my patient and Sky went deeper than motorcycles, their bushy eyebrows and olive complexion, and a build referred to as “buff.” I wanted to save this patient from a worse fate. I wanted his parents to be immune to the disease that afflicted me.

“You’re playing Russian roulette with your life.” I felt his hand squeeze mine.

“My belief is we all die when our time is up,” he said. “I’m not afraid of death. We all have to die sometime.”

“I don’t know, the bike just got away from me,” he said. The connection between my patient and Sky went deeper than motorcycles, their bushy eyebrows and olive complexion, and a build referred to as “buff.” I wanted to save this patient from a worse fate. I wanted his parents to be immune to the disease that afflicted me.

I wanted to put my arms around him and talk about a son who followed that belief. A son who thought he had nine lives and joked about his luck—a son who had two motorcycle accidents before the fatal one. A son who kissed me on the cheek for no particular reason two days before he died. Instead I just told him to be careful. I don’t want to burden others with my grief.

Twenty-six years have passed since Sky’s death, but the sense of loss lingers. I want to be reminded of him, the joys and the heartbreaks. I want to be around others with his interests, language, and gestures. And just like a child who grows up and leaves, so do my patients. They come and go like the change of seasons — something to count on, like the first rainfall of the year, or the scent of an early bloom. What remains at the heart of this is its humanity, its search for connections within the seasons of our lives.

Thanks for your beautiful story. I know well the need to find a lost one in the world. My partner passed away 4 years ago, and I still look for pickup trucks of the same make, model and color. I sends a jolt of life back intto my heart. I seek out older men in crowds, those with gray hair, a certain build, and a way about them that says I am here, and I tread this Earth. They act like the paddles on a defibrillator to reactivate my being. Is it just memories, or something else? I will never know, but i do known that there are days when it keeps.me.going..

Sadly beautiful, beautifully sad. Your eloquence creates welcomed rips in my heart.