On Pivoting

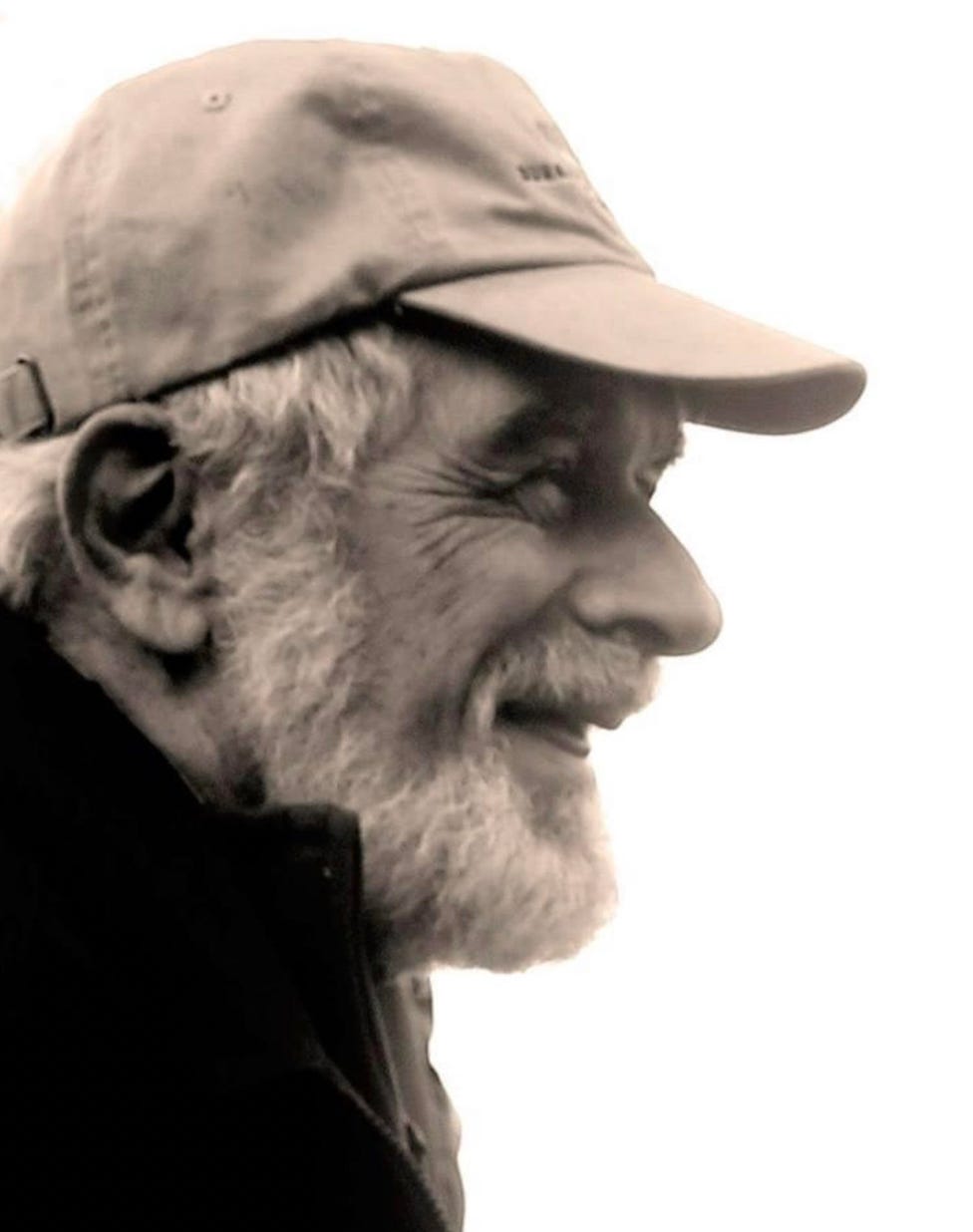

On Veterans' Day nonagenarian Paul Zolbrod, a Korean War-era vet, reminisces about how certain shifts at that time dramatically changed his life.

Some see a life as a trajectory, launched and on its way. Others see it as a pathway with a crucial pivot here and there, altering what might have been. That’s how my life went, thanks to being drafted during the Korean War, and all for the better.

To start with, something about the word pivot, which like other words has taken a turn or two. It entered the English language rather late, with the industrial age’s rise in the 19th century. According to The Oxford English Dictionary, it first turned up as a noun to specify “a pin or point on which a mechanism turns or oscillates.” Then it broadened to include “a person or thing that plays a central part or activity of turning sharply.” First as an intransitive verb to mean turn mechanically as if pivoted, then from there to apply transitively to willed human behavior. Someone pivots actively and deliberately. In other words, we can pivot or be pivoted. A piston rod makes the verb passive, the way a soldier does an about-face on command while marching. Or he could turn around on his own, say when he sees a pretty girl going the other way. Which makes him the doer of the verb’s action, not its passive receiver (with apologies for the grammar lesson).

Now to my story, starting in the summer of 1950, my high school graduation year, just weeks before the Korean War’s outbreak. Raised working class, I was not college-bound. After some floundering, I hired on as a delivery truck driver with Supreme Cleaners in a Pittsburgh suburb, picking up and delivering dry cleaning, pretty much my own boss, stopping for lunch when and where I liked, interacting mostly with young housewives raising kids during the prosperous post-World War II years when homecoming veterans finished college, launched careers, and started families.

I liked that carefree life. On Saturday paydays I finished my rounds early and left the shop with money to gas up my car, buy a round or two of drinks at the polka club, dance and carouse the weekend away, and return to work Monday morning—hung-over and nearly broke. But I got there, hustled through the week, kept track of who paid in cash or on credit, and recorded pick-ups and deliveries. Little did I realize I was being responsible. I was just having a good time.

My boss, Ernie, noticed, though. Just as he saw, too, that some mornings before a load was ready, I liked watching him trouble-shoot the basement boilers that steamed the upstairs pressing machines. A WWII navy draftee, he was a plumber’s mate on a destroyer and now an experienced steam fitter who could service those wild boilers that so fascinated me. Easygoing with me because I liked my job, and enjoyed helping him with those boilers that kept him from running the store upstairs, he sat me down one day after about a year, “to talk about where you’re going with your life. Or aren’t.”

“Is that how you want to spend it,” he challenged, “drinking and dancing?” Or did I hope to settle down someday, “with a wife and kids and make something of yourself?” With an only daughter not interested in the store, Ernie hoped to find someone to learn the business literally from the basement up, and take over someday, to apprentice first as a plumber, and eventually keep the boiler running. Was I interested? No hurry, he assured me. For now, just keep driving the truck, sowing my wild oats, helping with the boilers, and when ready, let him know. I could become a steamfitter and, if I liked, buy the business. Then I’d have a trade and a store. Fine by me.

My life’s trajectory seemed all set. Meanwhile, as we guys were being drafted, Ernie assured me our deal would await my discharge. Maybe by then I’d be ready to settle down with a gal and accept a “man’s responsibilities.” “Just choose the right one,” he said with a wink, “and make sure you marry because you want to, not because you have to.”

I had even found a good polka partner by then, Peewee Swetnovik, daughter of a shot-firer in the Cecil Township coal mine. My mother liked her, too, and I sensed that her dad saw me as a good son-in-law because I wasn’t headed for the mine myself. Peewee promised she’d write, accompanying my parents to see me off on February 10th, 1953, as I boarded a train with a bunch of others while the war ground on in what seemed an endless stalemate.

Pivoting on the ball of a foot. Pivoting by heel. Always on command, always in tight formation. You pivot passively to a drill sergeant’s command—a cog in a nation’s war machine, with scarcely a chance to activate a whim of your own…

Thus began that life-altering pivot into a war, which spun me with my very first short order drill on a crisp Alabama morning, when ordered to “fall in!” upon arriving at Camp Rucker with a Pullman car full of fellow Pittsburghers, joined by two or three busloads of strangers from elsewhere, to begin marching with Company B. Together we would share a barracks home for the next sixteen weeks, undergoing the ordeal of marching in step up and down the regimental dill area—starting all too abruptly with a barrage of passively executed pivots.

Whether performed on the march or spun by an engine, it’s done machine-like on orders: Forward march! To the Rear March! Column left! Column right! To the left flank, march! To the right flank, march! Pivoting on the ball of a foot. Pivoting by heel. Always on command, always in tight formation. You pivot passively to a drill sergeant’s command—a cog in a nation’s war machine, with scarcely a chance to activate a whim of your own—starting out with a hapless platoon of strangers struggling to stay in step, trampling the heels of the guy in front, having your own trampled from behind.

With each repeated drill, though, the entire company became as coordinated as the moving parts of a well-lubricated machine, marching straight ahead, or pivoting one way or another, without anyone missing a beat. Your life is not your own once inducted. Willed individuality vanishes with lost polka music, starting with a first G.I. haircut and the issuing of uniforms. Rise with reveille. Lights out with Taps. Eat in the mess hall. Stand at attention shoulder to shoulder. Pivot when told!

Every day regimented, every hour planned. Personal space crammed into fifty square feet of bunk, footlocker, and a clothing rack. Personal possessions limited to what can be squeezed into the bottom of a footlocker. March together to the mess hall. Eat what’s slapped on a tray with others. Shave elbow to elbow in a cramped latrine. Selfhood vanishes. To the extent you stay an individual, you’re a misfit. An “eight-ball.” Whether actively enlisted by choice or passively drafted no longer counts. All pivot together now.

Yet something repressed inside slowly emerges from pivoting on command. Or so I learned when following those orders as if by reflex. “With basic training the person you were disappears,” my big brother told me following his discharge after front-line service in Korea. “And the person you really are turns up.” He was right. I could polish my boots to my own satisfaction, I realized. I could push myself to run with the first ones charging up a hill. It was for me to decide how well I fired on the rifle range. My bunk’s sheets and blanket were mine alone to tighten. It was all a function of inner satisfaction. An inner pride. Pride in my company’s joint achievement was mine to claim, too. As I came to realize late one morning in the mess hall when kept behind for K.P., or “kitchen porter” duty.

All morning long I felt misplaced, cleaning up after breakfast and getting ready for the outfit’s march into the area for lunch. Basic training was better than half over by then. I had been forged as a soldier, which gave me a pride I maintain to this day. Together we progressed from raw recruits stumbling to march in step not as individuals, but as a disciplined unit, boots hammering the ground in syncopation, each man alert, erect, shoulders high, eyes straight ahead, chanting “Sound Off” in one voice. I could now internalize that as I watched my company march and pivot externally, standing there on the outside when I knew from within where I belonged. I was as proud to be part of that unit as I was sorry not to be in it at that moment.

Basic training was grueling, yes. At times life no longer felt my own. Days starting early, crammed with close-order drills, calisthenics, weapons training, indoor lectures, outdoor demonstrations, full-pack long marches, ventures single-file and shoulder-high through snake-infested swamp water with rifles held aloft, crawling shoulder-to-shoulder under live machine gun fire in driving rain, participating in an all-night patrol under the scrutiny of a field-grade officer. Throughout that sixteen-week cycle our self-regard was diverted in two directions: we were taught to kill an enemy yet unseen, and to put our own lives at risk to save the soldier visible next to us, whose life mattered more. All of which left little room for self-regard, but out of which pivoted the person we could each become.

Two weeks before basic training ended, an armistice was signed in Korea, where we were originally to have been sent. Instead, we were mostly assigned elsewhere. I was one of those, “lucky enough” to stay at Camp Rucker in that sleepy Alabama southeast corner. And “luckier still,” to wind up a clerk-typist in Headquarters Detachment, a cushy personnel unit, or so it was said. My job was typing out handwritten notations on military stationery.

Something repressed inside slowly emerges from pivoting on command. Or so I learned when following those orders as if by reflex. “With basic training the person you were disappears,” my big brother told me following his discharge after front-line service in Korea. “And the person you really are turns up.” He was right.

After basic training’s intensity, that humdrum life was not for me. The barracks were comfortable with individual rooms sleeping two, a stand-up locker for each bunk, and plenty of shelf space. The mess hall was declared the post’s best, and we could enter and leave as we wished. Workdays lasted eight hours, but each hour dragged by slowly, with evenings ours to fill as we pleased, leaving us to make little pivots for ourselves. Trouble now was, they were so small. I wanted something bigger.

I lived that way for five tedious months, with time on my hands to reexamine who I wanted to be next. I made okay friends and with them shared the boredom of a sleepy region, which seemed okay with them, but for me honky-tonk music replaced polkas. The small pivots I could activate on my own now hardly seemed enough. What movie to watch? Play cards? Stay on base and shoot pool? Hitch a lift into one of the nearby towns just for the sake of the ride there and back? Which: the post beer hall or the library? I found myself spending more time there, where reading “From Here to Eternity” by James Jones, or Ernest Hemingway’s “A Farewell to Arms” stirred me up more than Sundays could, just sitting on a park bench in nearby, sleepy Ozark ten miles east, or Enterprise fifteen west, each with its central square overlooking the town’s main intersection, girl-watching and wishing ourselves back home. I hated it, especially after basic training’s intensity.

Among my buddies, three in personnel recognized my restlessness, and in exchange for a fifth of whisky each, offered to doctor my record and reclassify me as a transportation specialist to fill such a position somewhere in the Pacific. “Of course, that might mean Korea,” they teased, which was still not an enviable place to be now that combat had ended. Never mind, I replied. I just wanted to get away from this place. I wanted to be somewhere with more to learn about life than I found here. I wanted to make big pivots, not little ones. I wanted to wear my uniform proudly where it mattered.

That turned out as the most pivotal fifteen dollars I ever spent. I wound up not in Korea but at Tokyo Quartermaster Depot, a military hotspot where supplies and equipment were being relayed across the Far East. To the Philippines where guerrilla activity persisted. To Formosa in support of Chinese Nationalists. To military attaches at embassies all over Asia. And most of all, to besieged French troops in Indo China, and to where under our very noses a Vietnam war was already brewing as I helped process shipments everywhere. All in a city and a country that opened my mind in undreamed ways.

Helped by the Japanese war veteran’s guidance, my curious pivots prompted me to continue my education. While awaiting my discharge, I applied to the University of Pittsburgh, where I went, graduated, and continued pivoting all the way to a Ph.D. and a long academic career well beyond dry cleaning’s tidy reach.

There were streets to explore, temples to visit, people in another country to observe, new foods to savor. More lastingly, that post’s Japanese librarian and I became friends as he noticed the books I was reading, and began inviting me to go camping with him and his friends. Which had me pivoting to places I would never have otherwise visited, high in Japan’s Alps and far along its shores. While traveling or over tea, we talked about books, culture, and world events, which widened my horizons all the more, with a well-traveled Japanese war veteran who had served in Manchuria. Helped by his guidance, my curious pivots prompted me to continue my education. While awaiting my discharge, I applied to the University of Pittsburgh, where I went, graduated, and continued pivoting all the way to a Ph.D. and a long academic career well beyond dry cleaning’s tidy reach.

Nor did marriage to Peewee materialize. Somewhere during that second year she stopped writing. Or maybe I did. In any case, after my discharge, I went back to tell Ernie, thanks, but I’m starting at Pitt. His wife Anne informed me that Peewee had married a miner and was now expecting a second child. Ernie, meanwhile, smiled, shook my hand, and told me I was doing the right thing. It’s what he should have done, he confessed, as Anne nodded in agreement.

Once my college education took hold, I realized I wanted to be a teacher and followed that path until retirement. With every class I taught, there grew in me an ever-deepening awareness of how basic training’s disciplined pedagogy conditioned me to value another man’s life more than my own. I didn’t always agree with what I was taught, but I appreciated learning how to pivot actively—less for my immediate self alone and more on behalf of others.

I am 90 years old but still remember very clearly basic training at Ft. Benning, GA in 1957. And, yes, my life did pivot when by chance I met a college friend in Personnel who got me sent to Ft. Belvoir instead of Advanced Infantry in Germany. Pivots by chance, pivots by choice but also pivots by accident. Great read, thanks.

A pivot from reduced self, to full humanity. Not bad, I’d say. Far better than a baseball double play.