Coming Up for Seconds in My Old Age

Taking inspiration from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 90-year-old Paul Zolbrod argues it's not too late for him to keep publishing—nor for a certain octogenarian president to run for another term.

Two elders competing for the presidency prompt a backward glance at Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, once this country’s best loved poet and the most celebrated. Start by looking at these eighteen lines from "Morituri Salutamus,"—"We who are about to die salute you"—a long poem he recited to his Bowdoin College 1825 classmates at their 50th reunion, encouraging them to keep busy, never mind their age.

ln his 70s, he would continue writing poems for several more years until just before his death in 1882. The passage comes near the end of his address, following a little tale he recites, reminding his listeners that it’s not too late to commit some act of vanity or greed. But there’s time left to do something creative, too:

But why, you ask me, should this tale be told To men grown old, or who are growing old? It is too late! Ah, nothing is too late Till the tired heart shall cease to palpitate. Cato learned Greek at eighty; Sophocles Wrote his grand Oedipus, and Simonides Bore off the prize of verse from his compeers, When each had numbered more than fourscore years, And Theophrastus, at fourscore and ten, Had but begun his "Characters of Men." Chaucer, at Woodstock with the nightingales, At sixty wrote the Canterbury Tales; Goethe at Weimar, toiling to the last, Completed Faust when eighty years were past. These are indeed exceptions; but they show How far the gulf-stream of our youth may flow Into the arctic regions of our lives, Where little else than life itself survives.

These lines offer something to think about now with two old men again vying for president. Readers of the poem can themselves decide how Longfellow’s homily might apply to Donald Trump; it’s President Biden I have in mind with this quote. And why not? In my 90s, I’ve just placed a book under contract about how much more I appreciate Milton’s Paradise Lost after assembling Diné bahane’: The Navajo Creation Story—my comprehensive translation of a long mythic cycle published by the University of New Mexico Press in 1983, still in print. Now I’m writing a memoir about that adventure, revisiting my past with a perspective age allows.

After a long career as an English professor and a lifetime of reading, I harken back to the first Longfellow poem I read in sixth grade, "The Village Blacksmith.” In it I admired the mighty smith’s “large and sinewy hands” and muscular “brawny arms” as he swings “his heavy sledge” at the “flaming forge” and with roaring bellows makes “burning sparks chaff from a threshing floor,” while children stop by after school to watch.

ln his 70s, Longfellow would continue writing poems for several more years until just before his death in 1882. The passage comes near the end of his address, following a little tale he recites, reminding his listeners that it’s not too late to commit some act of vanity or greed. But there’s time left to do something creative, too…

Such boyhood fawning matured to a more grown-up sentimentalizing when I read the poem again in high school. There I responded to how the widowed blacksmith listens to “the parson pray and preach” at Sunday church and then to “his daughter’s voice…singing in the village choir,” which sounds to him like “her mother’s voice singing in Paradise/” and “needs must think of her once more”:

How in the grave she lies;

And with his hard rough hand he wipes

A tear out of his eyes.Then follows a stanza in a voice characteristically Longfellow’s that recognizes a simple, hardworking craftsman’s prosaic existence:

Toiling,—rejoicing,—sorrowing, Onward through life he goes; Each morning sees some task begin, Each evening sees it close; Something attempted, something done, Has earned a night's repose.

As an English major in college becoming a more polished critic, or so I thought, I all but dismissed the poem and its author, affected by modernism’s post-Wold War I disillusionment and its more cerebral way of regarding poetry as opaque expression. According to that movement’s received wisdom, it was to be the poem’s inner vision to appraise, not its openly accessible expression of an author’s intent.

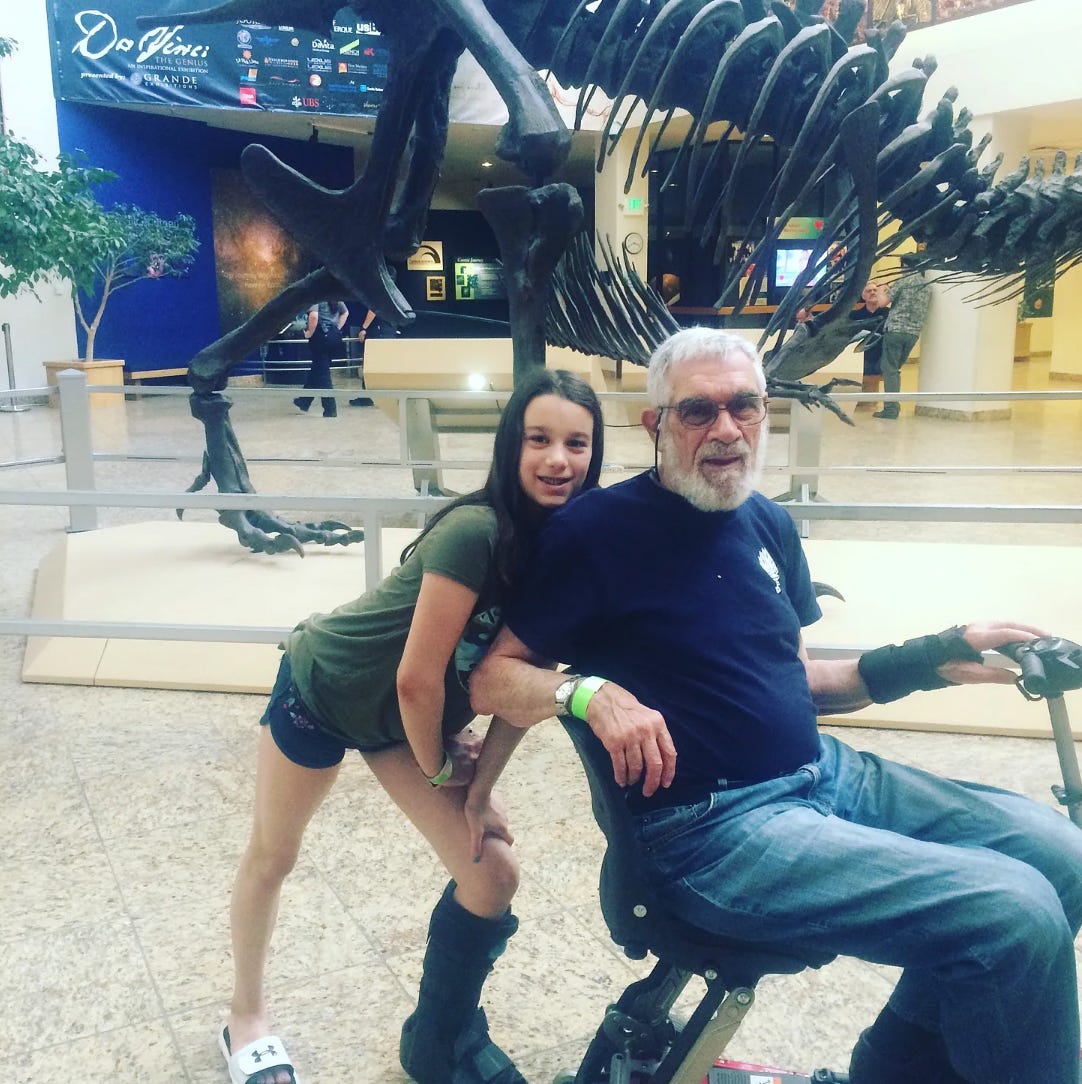

So here I am, a retired old gentleman embedded in the microcosm—writing another book like an aging president pursuing a second term. But where President Biden presides over this nation’s lofty galaxy of power, I legislate sentences and paragraphs to put together a second volume that can help bring a seemingly difficult literary masterpiece within a general reader’s grasp…

Years later, after exploring how indigenous oral traditions might shed new light on standard literary classics, I returned to Longfellow with renewed admiration. Ask others in my generation about reading him in school, and watch eyes sparkle with nostalgia. He was the first poet we studied as school children and learned to enjoy formal verse. Reminded now of his clear focus on commonplace people and events with transparent schemes of meter and rhyme, I see his lyricism summoning a vision likely to become a general reader’s own for the mind’s ear. In this age of broadcast media, it’s easy to imagine hearing the voice of Johnny Cash transcending the poem’s romantic sentiment in celebrating a hard-working, well-lived life. That’s where the poem’s lyric clarity lingers and invites reflection, rather than prying some attenuating irony out of its free verse, as today’s printed poetry often has a reader doing.

With the striving pretenses of academic life behind me, I enjoy writing for readers I can relate to as if personally—an unpretentious trait Longfellow brought to many of his poems. (In his old age, he even invited touring strangers into his home to chat.) In that spirit, I recently took to composing a series of imagined “Sunday Sermons” to introduce, in a new way, my Facebook friends to John Milton’s Paradise Lost as a poem they could tackle as ordinary readers rather than as students or scholarly critics. I did so experimentally when revisiting the poem in my retirement after having taught it professionally, just to share the pleasure of reading it with an old man’s ripened perspective. Which caught the attention of a publisher, who suggested turning it into a book. [Paradise Revisited: Lines from Milton’s Great Epic and the Navajo Creation Story: Pleiades Books]

So here I am, a retired old gentleman embedded in the microcosm—writing another book like an aging president pursuing a second term. But where President Biden presides over this nation’s lofty galaxy of power, I legislate sentences and paragraphs to put together a second volume that can help bring a seemingly difficult literary masterpiece within a general reader’s grasp: making my constituency one-on-one personal, whereas his is remotely public. Yet the difference withstanding, we both bring years of seasoned, ever-changing perspective to our respective realms—he for a second term summoning a full electorate to reelect him; I more modestly writing a second book after urging readers of the first to enjoy a fully intimate account of how of how the Bible’s Genesis merely sketches Adam and Eve’s fateful transgression.

To quote an aging Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, “Ah, nothing is too late.” We whose minds stay engaged while our bodies may not do what they used to aren’t necessarily feeble minded, so long as can apply ourselves to what we have always capably done.

Recently Elliot Cohen declared in The Atlantic that at his age, “The President has no business running for office again,” after such a long political career. Which is like telling me at mine I have no business writing one book then a second with my broadening appreciation for Milton’s Paradise Lost. Or maybe like declaring that Goethe had no business writing Faust after his long career as a poet. Or that old man Sophocles should have quit with Oedipus Rex, before writing Oedipus at Colonus. Doesn’t experience count for anything, with its widening perspective?

To quote an aging Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, “Ah, nothing is too late.” We whose minds stay engaged while our bodies may not do what they used to aren’t necessarily feeble minded, so long as can apply ourselves to what we have always capably done.

I loved Paul's piece and like another reader, the Johnny Cash comparison struck me. So many influences across the arts that one notices more and more when one ages, too. As an education editor, I've long revered Louise Rosenblatt's transactional theory of reading, that "the act of reading literature involves a transaction (Dewey's term) between the reader and the text. She argued that the meaning of any text lay not in the work itself but in the reader's transaction with it, whether it was a play by Shakespeare or a novel by Toni Morrison. " (Wikipedia). Paul's revisiting of poets and poems brings this theory to life. It also reminded me of my recent joy in learning that many young female singer/song writers are discovering Joni Mitchell, and that she is a big influence on their work. The more older artists keep doing their thing, the greater chance for younger generations to notice, and to invite their creative brilliance in, nurture it, and transform it.

Wow! I sent to Zolbrod’s academic home, Allegheny College, and while I never took one of his classes, he was very present to all of us who attended this small liberal arts college. What’s more, he’s been a remarkable mainstay at every reunion I’ve attended over the past nearly 50 years now. Passing this on to my college pals. Still sharp as a tack, he is.