Old Birds and Empty Nests

After her son flies the coop for to college, Sonya Huber reflects on the ways in which she, too, has been set free.

I’m a little over two months into the empty nest experience, a period that friends warned me might be weepy and overwhelming. To be honest, I feel amazing. I look great because I’ve slept, and the stress of leaving my son at school has calmed down somewhat. And it’s been a long time since I had impromptu sex in the kitchen.

Leaving him was one of those rites of passage that feel heavy and fiery because the moment has been so overwritten with the stories and images of others, and with my own memories. But I had practice, as I’ve been leaving him since he was 4 for visits with his father, who lives several states away. I’ve had to trust his well-being and his ability to navigate challenging situations, to fly and come back.

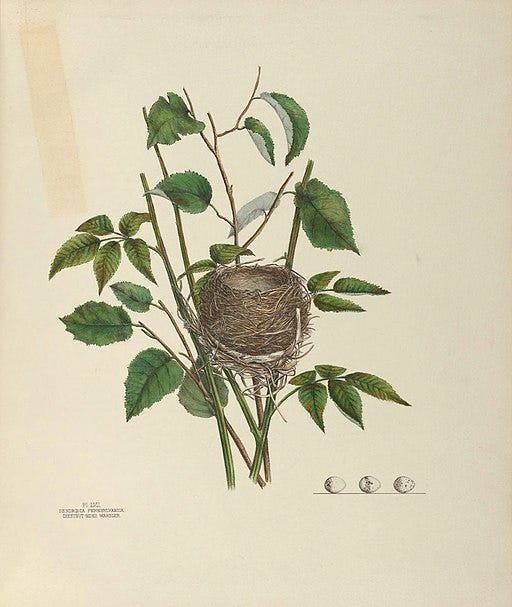

But that is the baby bird flying, not the nest. My son and I share a love of scavenging, picking up pieces of nature, so we’ve got nests, bones, skulls, feathers, and rocks tucked into shelves and boxes. And a bird’s nest is a marvel, each defined by a pattern associated with a species, created with local material, some messy and casual, some perfectly smooth inside like a teacup. The thing about a nest is that it’s built to be empty. That’s the nature of a cup, of any container: its emptiness, its holding capacity, is its strength.

I’m a little over two months into the empty nest experience, a period that friends warned me might be weepy and overwhelming. To be honest, I feel amazing.

The ability to craft a nest doesn’t die when the baby bird leaves. The knowledge, the container-building developed and passed on from bird to bird, flies away with the bird who built it. The mother bird also leaves the nest, which disintegrates or which some lucky child finds on the ground as a message from the world that safety and care can be built from grass and mud.

I love the nest I grew my son in, the empty space of my uterus, but that is now also discarded. I was overjoyed to get rid of it in 2018, when I was 47, because, like an old bird’s nest, it got weird and crumbly. Fibroids bled and poked me whenever I had sex, and toward the end, I was buying stick-on pain patches and wearing them everywhere.

So I went into my gynecologist’s office and she did an ultrasound and said things didn’t look too bad. She offered to check again in six months, but I’d seen enough of wait and see. I paused and said, “Y’know, if someone offered to give me a hysterectomy in the parking lot with a spoon, I’d take them up on it.”

I still remember her widened eyes, the silent way she regarded me. To her credit, she listened and scheduled surgery. I expected to feel all the ways: less of a woman, closer to death, functionless—I don’t know. I’m a crier, so I expected to feel sad and signed up for an online hysterectomy support group.

The thing about a nest is that it’s built to be empty. That’s the nature of a cup, of any container: its emptiness, its holding capacity, is its strength.

In the blur of recovery, my doctor came out of the operating room to show me pictures. “You were right,” she said. “They were bigger than they looked on the ultrasound, and one was pressing right on your bladder with what looked like teeth!” They weren’t teeth, but of course my uterus had grown its own kind of tissue-fangs.

I have to tell you: I love love love my uterine-free body. Within days, I felt AMAZING. I felt the way I remembered as a pre-teen girl, rangy and blank in my belly, not weighted down with a squishiness that expanded and contracted monthly with a mind of its own. And my doctor had taken out my cervix too, for good measure, and rigged up an artificial vagina by somehow attaching its top somewhere else. Were there bungee cords involved? I didn’t know, really, but I knew that I’d never had such pain-free sex ever in my life.

I felt more at home in my body than I’d felt since I was a 12-year-old, walking alone somewhere in my ripped jeans, thinking my own thoughts. And then, beneath that joy, slowly coming in like a change of weather, I felt a deep relief that brought with it horrific sadness for everyone with a uterus. I realized that the target on my back had been removed.

I didn’t really understand how much the weight of that bird’s nest had made me afraid, every single day of my life in the country, in this world. I had always known and carried in my uterus the knowledge that it contained the potential to grow my own captivity. The time bomb of one’s uterus can be triggered to allow a stranger to change one’s life, to alter its course by making one an unwilling parent. I knew this, but I didn’t understand it in my body—hadn’t understood the humming background noise of fear—until it was gone.

I paused and said, “Y’know, if someone offered to give me a hysterectomy in the parking lot with a spoon, I’d take them up on it.”

I grew up knowing that getting pregnant could fuck with my access to education, books, work, and freedom. I had experienced the desperation of not being able to afford daycare which I needed to earn money to feed my son, the mobius strip of want that leaves parents completely unprotected in this country, by design, so that we are less free. And I’d felt the million arrows of discrimination, and had paid a sort of uterine tax every month before the Affordable Care Act, more expensive insurance because I could grow a child. And all that was gone: my biggest physical vulnerability was gone.

Even without my uterus, I was still a mother. The mothering—all the really hard work—had taken place outside of the uterus, just as his amazing next phase of growth is going to take place outside of the nest. The process of mothering changed me, and that is what I want to retain. The nesting and the raising changed this old bird. It must take a fierce patience to turn sticks into a cup.

Mothering made me learn and practice kindness and patience, but also a wily scrappiness and a direct rage at whatever threatened me and my brood. And my mission now is to turn that kindness and patience toward myself, to apply all those skills to my own still-growing life.

I’m a tree free of nests, and it is glorious to feel the wind rushing through my branches. I’m a walking tree, I’m a bird considering migration.

I would recommend this emptiness to anyone. I treasure this blankness. My son is fine at college. It’s where an 18-year-old boy needs to be: out in the world. I’m a tree free of nests, and it is glorious to feel the wind rushing through my branches. I’m a walking tree, I’m a bird considering migration. The explosive and unrestrained uterine energy has been transferred to my entire life, to whatever comes next.

This is amazing!!! Another great example of why Oldster makes my life better. Thank you for writing this. I am not a parent, but I really needed to hear the hysterectomy part, and no one talks about that shit.

A walking tree, free of nests. Sonya, the way this essay sways and bends and returns to standing upright (yes, of course I extended the metaphor) is a joy.