Letter to My Younger Self #6: Rearranging My Nervous System

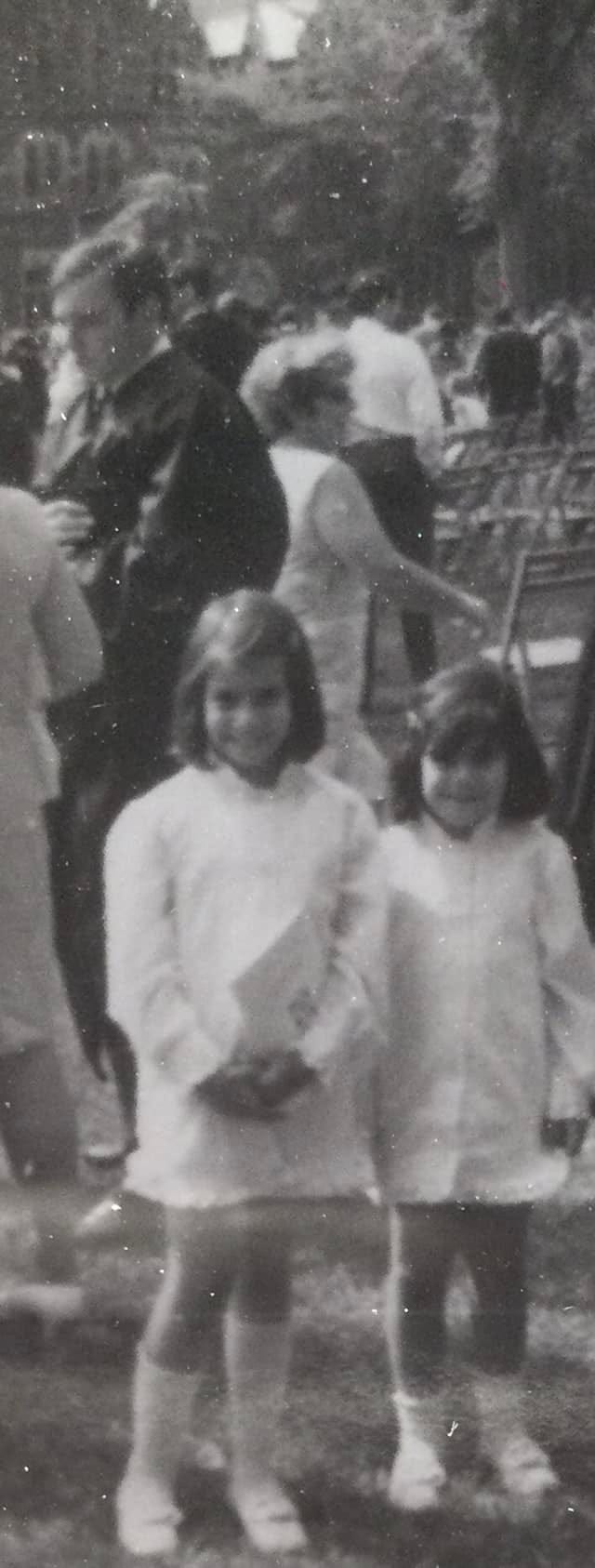

At 62, Judy Bolton-Fasman sends encouragement to her inner first-grader, whose love for Wednesday Addams and dancing badly helped her survive racist bullying.

Dear young Judy:

People were always telling you to smile. A smile is just a frown upside down, your teacher said. It was 1967 and the verdict was that you were gloomy. Gloomy Gus your first-grade teacher called you, and the kids echoed the taunt. You did not know how to be any other way. But you had a role model, an anti-hero in Wednesday Addams. You loved Wednesday, the fearless young daughter in The Addams Family. You blessed the Sabbath candles with your mother every week, sawed through her burnt brisket, and washed it down with Welch's grape juice. Afterward, you were scrubbed and pajamaed by 8:30, just in time for the snapping that signaled the show's beginning. You practiced snapping until the pads of your fingers hurt.

You were the daughter of volatility in the person of a Cubana mother – carrying a version of her weirdness, her oddness in your DNA. Your family was not like the others in West Hartford, Connecticut. For one thing, you were the only kid who rode the Asylum Avenue bus with your non-driving mother. If it wasn't on the bus line – your allergy shots, violin lessons, and Mamá's manic shopping sprees – you and she did not go.

You learned to read sounding out the bus ads as you tried mightily to avoid the ad asking in thick black letters: Why Does Johnny Wet the Bed? More to the point, Why Does Judy Wet the Bed? By age 8, you were stripping your bed almost every day before anyone was awake. You trudged down to the basement to stuff your sheets in the washing machine. You did this despite being afraid of darkness and dankness, and the place where your mother said that Babajiniji, the Sephardic Turkish monster, hovered.

You were the daughter of volatility in the person of a Cubana mother – carrying a version of her weirdness, her oddness in your DNA. Your family was not like the others in West Hartford, Connecticut.

But your fear of it being found out how often you wet the bed trumped any monster. Bedwetting was the monster in your life. So, here's what I want to tell you, young Judy, about wetting the bed and, for that matter, everything else that hurt you: none of it was your fault. Maybe you had a small bladder, but more likely, you woke up in urine-soaked sheets because worries and problems weighed down on you. That heaviness pressed on your chest, and it seems, your bladder. You will also grow up to understand those worries and problems constantly unfolding in your house were not catastrophic after all. There will come a moment, long into the future, that will crystallize with the knowledge that your magical thinking and prayers were your survival strategies, and they were good ones too.

Let's talk about those worries and problems for a moment – the stress of your mother's plate-throwing temper, the stress of having insults like ”Spic 'n' Span” hurled at you throughout elementary school because your mother had a Cubana accent. Or the stress of thinking up excuses to avoid recess in case a dog wandered onto the playground. Like your mother and mother's mother, you were deathly afraid of dogs; it was among the fears passed they down to you. Given the anxiety you desperately harbored, it's a miracle you only wet the bed. I want to walk you back through the decades and tell you how wondrous you are. If I only I could hug you, dear one. You were like the silly putty you loved to press to pick up images of the Sunday comics. So many images were imprinted in your mind. Yet, your silence about them formed a resilience that forged your strength in foundry-like fire.

Remember how you mimicked Wednesday’s deadpan charm? Wednesday Addams was the epitome of cool mostly because nothing stuck to her – neither her parents' bizarreness nor her little brother's annoying antics. Wednesday was solitary and powerful. And she dressed in black, something you were not allowed to do. But you, too, had power and strength, young Judy. You didn't know it yet.

Weird – that was a word you heard a lot back in elementary school. You were called weird because your mother, terrified that you would be kidnapped, picked you up every day from school. “Baby, baby,” the kids teased. One time you glimpsed a police sketch in the newspaper of a man who had allegedly kidnapped a young girl walking to school, and he looked like your Uncle Max. Like so many observations and thoughts you had back then, you kept the coincidental resemblance to yourself. You were not sure why you were so afraid.

Your fear of it being found out how often you wet the bed trumped any monster. Bedwetting was the monster in your life. So, here's what I want to tell you, young Judy, about wetting the bed and, for that matter, everything else that hurt you: none of it was your fault.

You were also branded weird because you had no rhythm on the kickball field or square dancing in the gym. Imagine, a Latinx kid who couldn't follow a beat. But please understand, you followed your own beat, especially when you swayed to Cuban music in the living room with Mamá. You were creative, extraordinary. My little Judy, weird is impressive. Weird is weird is weird like Gertrude Stein's rose. You will come to know that Stein captured the beauty and essence of the thing she repeated.

Your favorite, Beny Moré, sang his way into your heart. Llaro, Beny's made-up word – or maybe a word you misheard – he shouted as a call to action. Llaro, a sound we screamed back. Beny's big Cuban voice and formidable brass section rearranged your nervous system. Bundled neurons gave way to your dance of disconnected movements. If you were a musical composition, you would have been all minor chords. You flapped your arms like a hummingbird and improvised hopscotch-like steps across the floor. You twirled until the world blurred, and you felt the earth rotate on its axis.

You bucked against tempo as you played your mother's castanets just like the ones Morticia had. Dalé, dalé, Judy – the Cuban idiom for hitting the gas – encouragement someone should have whispered in your ear as you danced. Mamá's right hand on her belly and left hand raised in the air as she languidly moved; her Cuban melancholia is forever inside of you. However, darling Judy, your choreography was wild and gorgeous in contrast to hers, which was small and sad – triste es triste es triste. Back in the 1960s, Cuban exiles owned the word triste – deep sadness. And so did you with your sweet upside-down smile.

When you were a young teen, you retreated to your room to dance alone. You had a new transistor radio, small and gold and poked with holes through which Top 40 wafted. Your world expanded. It didn't matter to you that the music was tinny and competed with AM static. Static didn't bother you – you were used to your mother's worn and scratched up Cubana records. The music rose above those incidental sounds, and you moved to it, supplying your idiosyncratic rhythm. You loved to slow down your dance moves when you listened to Helen Reddy sing 'Angie Baby.' 'You live your life in the songs you hear/On the rock and roll radio/And when a young girl doesn't have any friends/That's a really nice place to go.' You and Angie were weird and mysterious, and you beautifully inhabited the mystery.

Imagine, a Latinx kid who couldn't follow a beat. But please understand, you followed your own beat, especially when you swayed to Cuban music in the living room with Mamá.

I wish I could travel back to 14-year-old you and show you my children, friends who love and respect me, a husband who tells me how much he loves me every day. Judy, trust me; when you grow up, it will feel so good to return that love. But most of all, I wish I could show you the teenage Wednesday Addams in her mini-series called Wednesday on Netflix. You would love it. The title is straightforward like Wednesday. Except there is nothing straightforward about this girl. She is clever and magically accesses vital resources as needed. And her glare breathtakingly blows away a frown turned upside down.

When Wednesday performs the “Wednesday Dance” midway through the series, you take notice because she has something to say, something to show that everyone wants to hear and see. Her dance moves are disembodied, theatrical, elbowy. Wednesday's stony façade reflects her defiance. And she mixes theatrics, eccentricities, and even glimmers of humor into her dance. She boldly, un-self-consciously celebrates weird.

I celebrate Wednesday and weird on your behalf. And dear young Judy, I am writing to you at 62, which is also joyously weird. Bring out the castanets and let's dance. But most of all, I want to thank you for the strength you had to bring me to this day and season of joy.

With all our hard-won wisdom and love, your friend and admirer,

Judy at 62

Weird kids make the best adults. Thank you for this, Judy. xo

Judy Bolton-Fasman, your essay is amazing. I am 62 and grew up in Connecticut, where the Ct. River hits Long Island Sound. Different culture but same anxious growing up and complex family. Brava that you evoked so much in so few words and delivered fresh insights in a sea of reflective essays about growing up. I'm gonna remember this one forever. Thank you.