It's a Long Way Down

"Like hundreds of thousands of men in their early 60s across the country, I was forced to start to get used to the idea that the marketplace may be deciding that I am 'done.'”

I was waiting for the light to change on a busy Washington street corner. My then- teenage daughter asked, just as the light started to change, “Dad, what are you afraid of?” That kind of question might have been a cue, the opening, for a heart-warming father-daughter conversation about life’s challenges and how to overcome them. Not today. From my reactive, lizard brain, or from somewhere lower, in the primordial soup in my guts, came an answer that I didn’t even consider: it came out of my mouth before I had even had a conscious thought of it.

“Being poor. That’s what I’m afraid of.” And we headed across the street.

My oldest friend, who grew up in a well past-its-prime Brooklyn apartment building across the street from mine, laughed when I told him about the conversation, and then, got quiet. “I’d probably say the same thing. But you probably scared her with that answer.”

Yeah. That answer was probably a lot more than she figured on getting when she asked an innocent question!

When I used to read personal finance columns warning older workers could face sudden and catastrophic losses of income in their final working years I was empathetic, but concluded “That could never happen to me.” After all, I had worked hard to build in bumpers around my life, and my career, to keep that from happening. I followed the advice from the Big Voices in the culture, and followed the rules: I finished high school. I was the first person into my family to go to college, and eventually get a graduate degree; I got married and stayed married; I saved, I paid off my mortgage years early; and paid in full for three college educations so my kids wouldn’t have to borrow. I did all the things that make the cover of Money Magazine.

When I used to read personal finance columns warning older workers could face sudden and catastrophic losses of income in their final working years I was empathetic, but concluded “That could never happen to me.” After all, I had worked hard to build in bumpers around my life, and my career, to keep that from happening.

Just the blink of an eye ago I was anchoring a nightly news program for the cable news network Al Jazeera America. Before that I had long tenures with the PBS NewsHour and NPR. There is an accumulating, insulating impact of decades of high-paid work. Running around the country and the world also ushered me into a pampered class of business travel, met at airports by drivers holding a sign with my name, who whisked me to a hotel where I was thanked for my travel status at the front desk, and often enough, offered a room upgrade. I had a solid resume, and a considerable body of work to show a future employer. Three books with major publishers, a long list of awards, well-regarded work in tv, radio, and print. I didn’t feel like my career was precarious. If something went wrong, I’d just find something else. My 60s had begun, but finding the next job would be easy. What did I have to worry about?

When the pandemic started to shut the world down I dreaded returning to my desk in my home-office, as the in-box only brought coronavirus-driven bad news. A paid speaking engagement in Texas? Cancelled. Several days of work at an international NGO conference? The organizers decided not to take the risk. A very well-paid gig moderating a climate change conference in Chicago? Postponed. Maybe until October. Or maybe never. When I had travelled as a reporter to health crises in Africa and Latin America in recent years, exposed to malaria, tuberculosis, and pneumonia, I always knew that if I got sick my health care costs were paid by my employer, as were any days I needed to recover. In Haiti, after the devastating Port au Prince earthquake, I caught something that lingered when I got home, and just called in sick. Now, as a gig worker over 60, “sick days” are simply forced days off, unpaid. Get well soon!

How common is that story? The insurance and employee benefits firm MetLife estimates 30 million workers, a fifth of the entire labor force, now get their principal salary from gig work. If work dried up, my $2800 a month insurance bill still comes due on the first of the month. The electric company won’t take a podcast, a column, or a television documentary as in-kind payment for this month’s kilowatt hours.

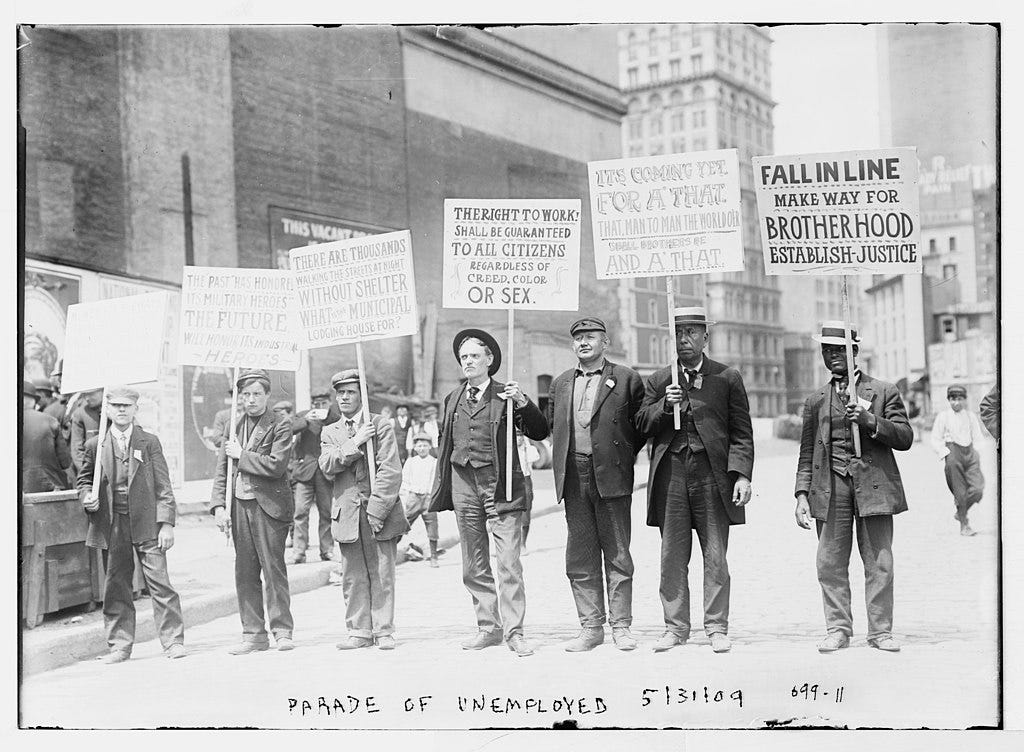

In the first two decades of this century, wages declined for working men with bachelor’s degrees over 55 years old. When men over 50 who are displaced from their last job finally get another one, they can expect their wages to drop 20%. For women the same age, the drop is even worse, on average the new job pays 36% less than the old. Those declines in the midst of a supposed economic and labor market recovery signaled the decreasing bargaining power of older men.

I had a solid resume, and a considerable body of work to show a future employer. Three books with major publishers, a long list of awards, well-regarded work in tv, radio, and print. I didn’t feel like my career was precarious. If something went wrong, I’d just find something else. My 60s had begun, but finding the next job would be easy. What did I have to worry about?

In a downturn, older men do hold on to their jobs more regularly than younger ones, but when they lose work it takes them considerably longer to find the next job. Men older than 55 can’t command higher salaries in the marketplace, but they also can’t walk away and rely on their savings which, for millions, are inadequate. Northwestern Mutual has reported that one in three Baby Boomers, knocking at the door of retirement, has less than $25 thousand saved. A study from The New School estimates that 8-1/2 million older workers over 55 would fall into federally-defined poverty if they retired at 62 and began taking Social Security payments. It is, the researchers found, the end point of more than 20 years of lagging behind younger men in wage increases, both among college-educated and non-degree-holding men.

Then the wheels came off. After Al Jazeera pulled the plug on its young network, I headed to Amherst College as a visiting professor, while beating the bushes for jobs in radio, television, and print. I did not unravel. I calmly began calling old contacts, and applying for jobs I “qualified” for by every objective measure. I shoved down any rising panic, kept one eye on my bank balance, and starting freelancing, all while keeping an eye out for my next Big Thing. I had to reckon with the idea that the long-ago magazine article warned about, there might be no “big thing.” Like hundreds of thousands of men in their early 60s across the country, I was forced to start to get used to the idea that the marketplace may be deciding that I am “done.” Many men my age are “job bound,” imprisoned by their conviction they couldn’t find a comparable job at a comparable wage, even in a tight labor market, the way their young co-workers do.

“What’s this about? Corporate greed. Greed has a lot to do with it,” says Nick Corcodilos, author of the “Ask the Headhunter” blog and employment consultant. “I’ll get a guy in my office who’ll tell me ‘I was making $150 thousand. I’m scrambling to get jobs at 115, or 100. I just need a job.’ They’re squeezing them. They figure, what are the odds they’re going to get a better offer?”

“It’s never a great idea to squeeze people just because we can,” said Peter Cappelli, Director of the Center for Human Resources at the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania. “There is certainly harm to individual employers to overlook candidates who, on average, have better work skills, better interpersonal skills, don’t need training, and are more inclined to be helpful. There is clearly harm to society when we have people who can and need to work more years and can’t because of discrimination, just as there is harm with similar biases against other groups.”

Corcodilos adds, “You’ll hear explanations like, they cost more, their benefits cost more, they’re out more often because they’re sicker. It turns out, it’s all BS.”

Along with the emotional work involved in recalibrating who you think you are in the world, realizing people won’t answer your calls, and a constant gut-check over the values of your skills and experience, there is a practical side to all of this to my anguish.

In a downturn, older men do hold on to their jobs more regularly than younger ones, but when they lose work it takes them considerably longer to find the next job. Men older than 55 can’t command higher salaries in the marketplace, but they also can’t walk away and rely on their savings which, for millions, are inadequate.

As my COBRA health coverage reached its time limit, my wife and I had a long talk about how to lower our enormous monthly health care costs. One quick fix was to drop dental coverage to lighten the load. Just two weeks later, I was riding my bike on DC streets. I hit an enormous, and unexpectedly deep pothole. The shock to my front wheel slammed my jaw shut, hard. I shook it off and continued to pedal. Then the pain began, a searing pain that subsided into a steady, throbbing ache radiating from my jaw to my eyes, to the top of my head. It felt like my teeth were now misaligned. I was having trouble chewing food.

In just a few weeks I had moved from being a guy who had top-drawer health coverage to one of the guys I read about, one of the guys I covered, who deferred health care for fear of the cost. I waited. I took aspirin. A few weeks later all the swelling inside my mouth subsided, as did the pain. I’m holding off on having that molar repaired until I get a job with dental coverage. But what if I never get that kind of job again?

I am still years away from what I thought of as the age when I could start the transition to part-time work. I have worked hard to avoid taking money out of retirement savings to cover current expenses. Repairs I would have had done at home without a second though have to wait until there’s money. The front steps need to be re-mortared and reset. A dying tree in the yard needs to be cut down and carted away. Those things must wait. After solid and sustained planning, I’m a rich guy with no money. It’s waiting for me, a couple of birthdays down the road.

When I wrote about this for the Washington Post in 2020, I really wanted to spark conversation about ageism, about the challenges to older workers. The online version of my article eventually got 4 thousand responses…and the responses themselves were a lesson about where we’re at today:

Some were filled with resentment, and vitriol…implying the only reason I had a career in the first place was because of affirmative action. Lots of responses imagined for me, grafted onto me, a life of sybaritic luxury…fancy cars, swanky vacations, private school tuitions, that I purposely didn’t live in order to save for retirement. Others were sympathetic…responding with their own stories of forced early retirements, vicious ageism, and turning to savings earlier than planned. Some people rapped me for leaving the PBS NewsHour, where I could have worked until I retired…some for paying for my kids’ college educations, one for having the nerve to ride a bicycle on the street at my age.

In just a few weeks I had moved from being a guy who had top-drawer health coverage to one of the guys I read about, one of the guys I covered, who deferred health care for fear of the cost. I waited. I took aspirin. A few weeks later all the swelling inside my mouth subsided, as did the pain. I’m holding off on having that molar repaired until I get a job with dental coverage. But what if I never get that kind of job again?

The lack of sympathy, the lack of empathy, the resentment, even the cackling at my predicament, told me a lot. Lots of people are trying to come to terms with narrowed horizons, cramped futures…and they’re pretty pissed. But really, DON’T pay for your kids’ college? Come on, man….

The drop in living standards and rise of money worries are real enough. Less tangible, but only slightly less daunting is a sudden insecurity about self-worth, status, and place in the world. My name appears on mailing lists from my days as the old me. I’m asked to make generous contributions to organizations I had written big checks in the past, and simply can’t now. As the lockdown loosens up there are opportunities to put on a suit a guy who makes my current income would never be able to afford, to hit the heavy hors d’oeuvres and hear a book talk or watch a screening. At these events I scan the room for people who may be hiring, and realize I am probably the only person in the room who is looking for work.

I’m not whining. In fact, I feel sheepish talking about this stuff at all, because I know how many live a lot closer to the edge than I am. Yet, life is different. I head into the supermarket and first do a walk-through with my wife’s list in hand, to see if items close enough to what’s specified are on sale. A pair of old shoes is resoled for a second time instead of being replaced. There will be no vacations for my family when this crisis ends.

However, that doesn’t change the fact that I still have some serious decisions to make about what this particular chapter of my life, and what’s left of my working years, can be. If for once I don’t follow the rules, take my Social Security early and start drawing from my 401(k) accounts, I will be poorer in retirement than all my planning and saving ever assumed. I can swallow hard, and realize a part of my life may now be over…a part, frankly, that I never expected when I was growing up in a Brooklyn apartment house.

But that would mean proceeding on the theory that a cratered annual income is now the reality for the long haul, rather than just an aberration. I have to scratch together the dough for my property tax, my homeowner’s insurance, and my monthly premium. I’ll keep an eye on the calendar and cross the line to Medicare as so many friends have begun to do.

One thing I don’t ask, never ask, is, “Why me?” Given my age, given the numbers, given the realities of work in America I could just as well ask, “Why not me?”

Heartwrenching and relatable, reading this essay. Ray Suarez you are a revered figure for me, as a longtime PBS Newshour viewer. So many layers to all this. I am going on 63, and I hear you. Some of it is corporate greed for sure. We are the last year of the baby boomers set, and unique in that we were shaped by the post-War values and sense of prosperity and endless American greatness, yet came of age in the late 1960s and 1970s, we so absorbed the art and counter culture ethos without being drafted to Vietnam. We entered a workforce that seems unprecendented in terms of requiring 24/7 work, but we did it. I am an editor, doing freelance by choice, and knowing that if I took on full time work it would require far too much. I had seniority and clout by the time I became a mom, but even then I saw that to reach top salaries in publishing world would take too much away from my family. This is a travesty that is too common in this country. Two of my brothers are doctors/surgeons and their careers were punishing. Business schools, med schools, media empires, insurance companies all set up to make only a few rich. High schools do need to teach financial literacy, that's one small piece of the pie here. As I look at my college and career friends and how they are faring, and my own status, I see how it's hard to be true to yourself and your dreams and be cunning about money. It shouldn't be that tough, though. This country is so in need of fixing.

This is SO important! I did not have the career Mr Suarez had, but l have worked on the PBS side of media for nearly three decades. I also graduated two children from college without any debt on their shoulders. Once I got to my 60s, however, it was quite a shock to crunch the numbers and realize I couldn't afford to live in the US once I stopped working even with Social Security. Life is different, indeed.