In Memoriam: Lesley Lenore Pitts

Looking back at the love of my life, 25 years after her passing.

The afternoon in 1991 when I met Lesley Lenore Pitts, the love of my life, I was only 28, but had already damn near given up on love. Though I was young, I felt weary beyond my years, thanks to a few failed relationships throughout the 1980s. These were perfect conditions, in hindsight, for Cupid to step in and take me by surprise.

But, I’m getting ahead of myself. Our story actually begins a little bit over a year before that day.

***

In August, 1990 I met photographer Alice Arnold at an editorial meeting for music magazine Soul Underground. Though it was a British publication, its editor-in-chief—Leonard Abrams, who a decade before founded and edited the East Village Eye—was based in New York City. The meeting was held at his Lower East Side apartment. Writers Kim Greene and Bonz Malone were also in attendance. I became friends with them all, but it was Alice I grew closer to, adopting her as one of my sisters.

The afternoon in 1991 when I met Lesley Lenore Pitts, the love of my life, I was only 28, but had already damn near given up on love. Though I was young, I felt weary beyond my years, thanks to a few failed relationships throughout the 1980s. These were perfect conditions, in hindsight, for Cupid to step in and take me by surprise.

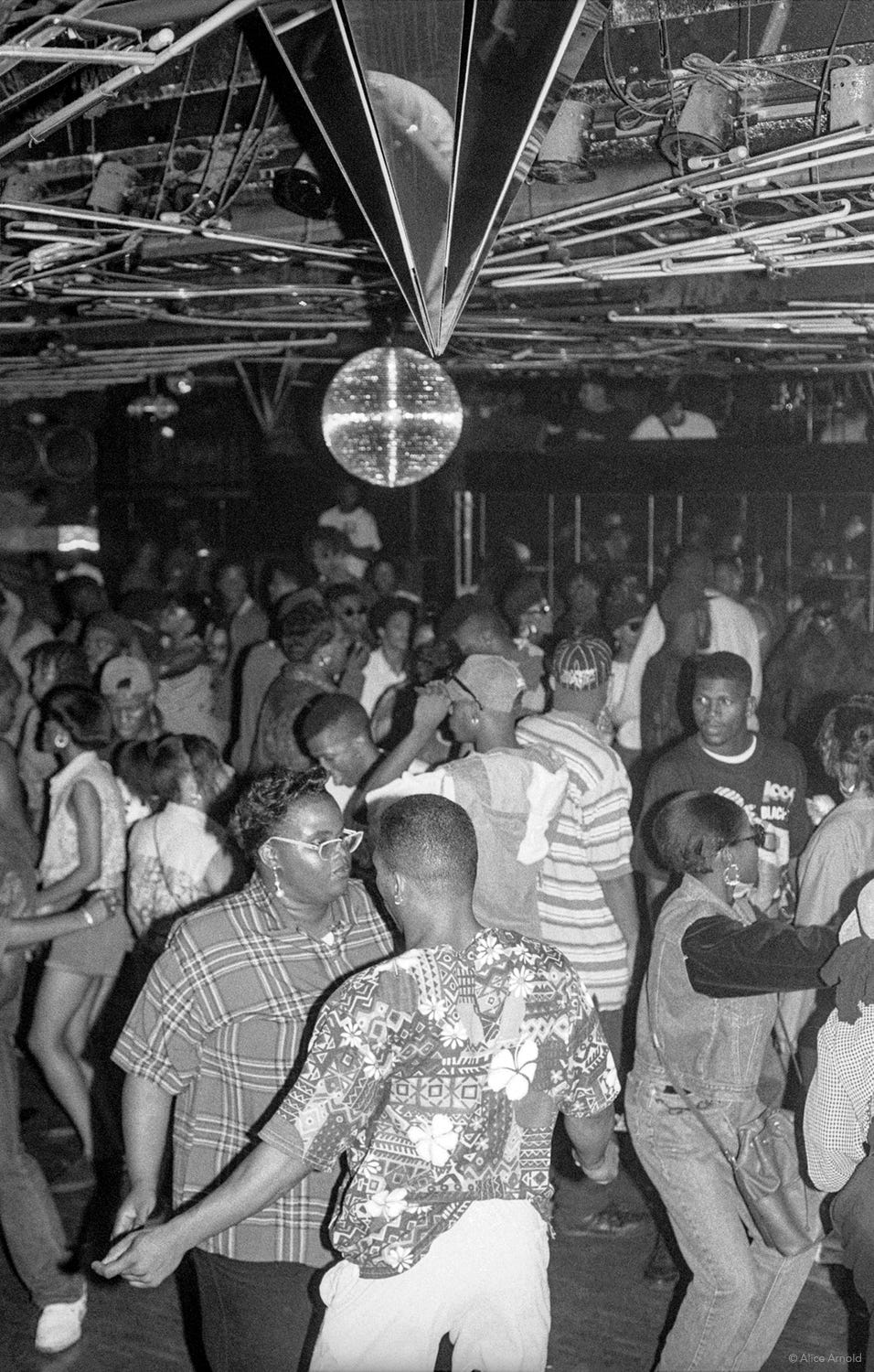

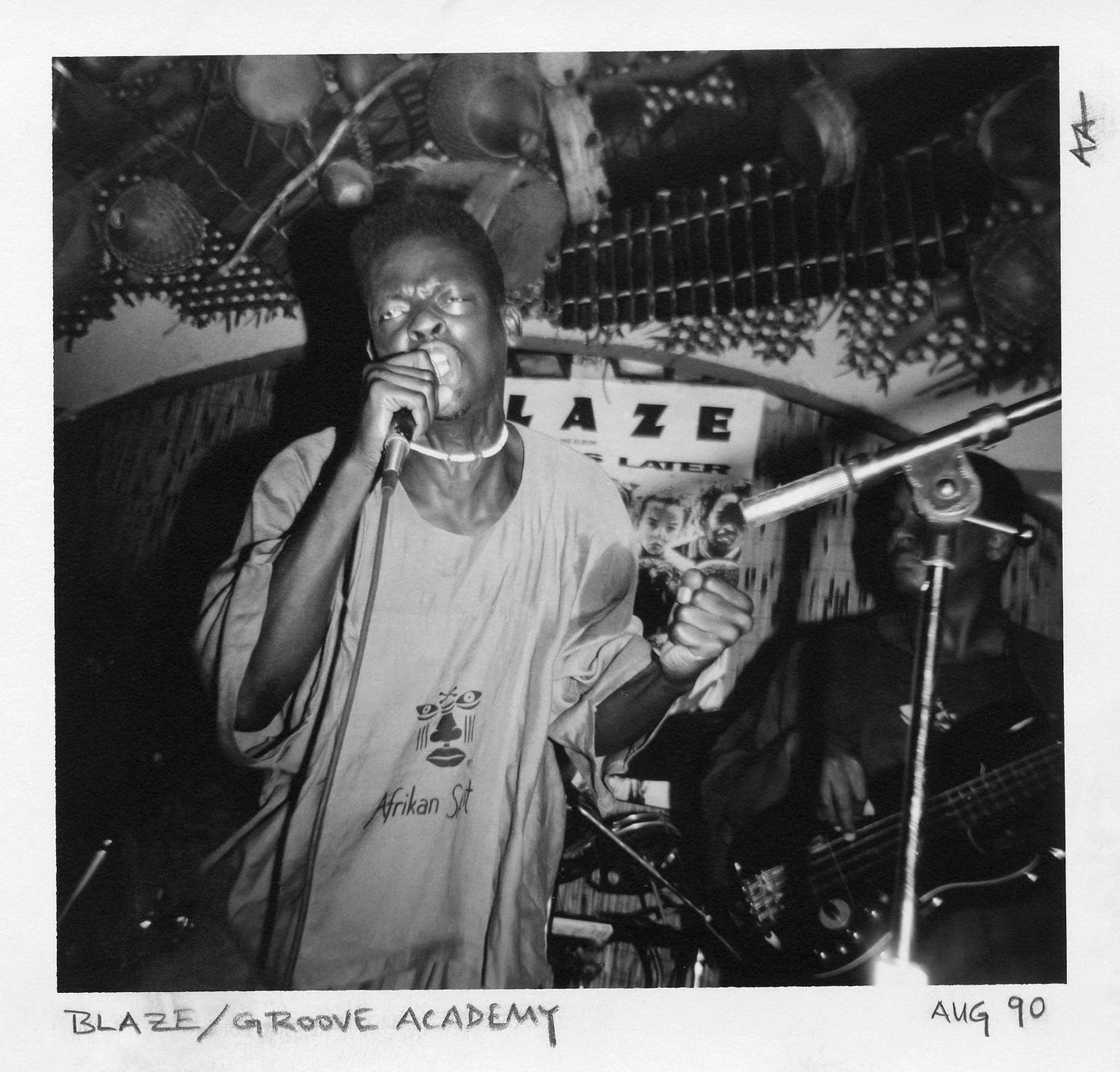

During the next year Alice and I hung-out together at various cool downtown clubs while attending the Groove Academy/Giant Step parties, which, in the 1990s, drew folks from diverse backgrounds who listened to alternative hip-hop, old soul, vintage jazz and classic funk. One of the first shows we attended together that August was at S.O.B.’s (Sounds of Brazil) for the release party/performance of a house music group called Blaze.

Signed to Motown Records, their album 25 Years Later was Blaze’s major label debut, with the single “We Must All Live Together” a sensation in dance clubs, especially Zanzibar in their hometown of Newark, New Jersey. The band performed, and people danced hard, while Alice took pictures and I sipped a cocktail. She used a manual Nikon 35mm camera or a Hasselblad. Back then there were of course no camera phones, and digital photography was not yet commonly used. Alice shot rolls of old school film, which she later processed and developed in her darkroom.

Sweating heavily in the already humid venue, I leaned against a pillar and observed as the crowd had lost themselves in the groove, skillfully moving to the band’s soulful sound. Though I didn’t know it at the time, one of the bodies moving blissfully on the dance floor was my future girlfriend, a beautiful young music publicist named Lesley.

Like Blaze, she, too, hailed from Newark, and had been a regular at Zanzibar. Lesley, as I learned later, hung-out in Blaze’s dressing room prior to their going on stage, and for the length of their show set the floorboards on fire. In that dark club crowd I didn’t notice her. However, after we met a year later, she shared that story, and I knew we had been in the same room that night.

In August, 1990 I met photographer Alice Arnold at an editorial meeting for music magazine Soul Underground. Though it was a British publication, its editor-in-chief—Leonard Abrams, who a decade before founded and edited the East Village Eye—was based in New York City. The meeting was held at his Lower East Side apartment. Writers Kim Greene and Bonz Malone were also in attendance. I became friends with them all, but it was Alice I grew closer to, adopting her as one of my sisters.

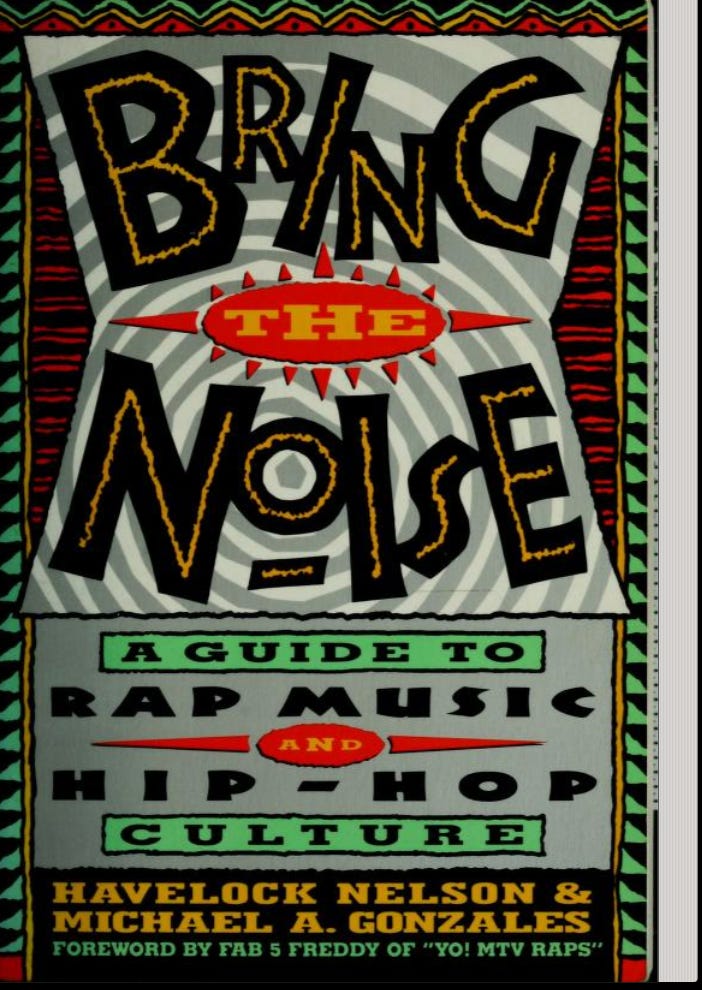

After the Blaze show, I took the Brooklyn-bound subway back to the East Flatbush basement apartment I shared with my friend Havelock Nelson. We were both “hip-hop writers,” writing articles for Word Up, Billboard, The City Sun and Black Beat. It was in that cellar where he and I worked on our debut book Bring the Noise: A Guide to Rap Music and Hip-hop Culture, published the following year by Harmony/Random House. With our small advance we were expected to also pay the photographers. Thankfully we had cool friends who were willing to help us out. Tina Paul, Ernie Paniccioli and, of course, Alice, had shots in the book. Alice also took our author photos and publicity pictures.

With the book dropping in November, 1991, on August 9th we had a meeting with the publisher. Afterwards Havelock suggested we walk downtown to Set to Run, a publicity firm that repped many rappers (A Tribe Called Quest, Public Enemy), to hang-out with the publicists until our next engagement. In that Sliding Door moment, if I had chosen to go to the movies (I was fiendin’ to see Barton Fink, released a few days before) instead of office-hopping, my entire life would’ve been completely different. Instead, I went upstairs and, after noticing Lesley working behind a cluttered desk, walked through that open door, sat in the chair opposite her, and introduced myself.

Lesley, in the words of writer/friend Amy Linden, was “a broad.” One of those smoking (Newport 100s), drinking, cursing women who, though well-read and college educated, could hold her own in a bar brawl or street fight, a Scrabble game or a Dozens match, against an obnoxious cab driver or a rude hostess at some fashionable restaurant.

Lesley, in the words of writer/friend Amy Linden, was “a broad.” One of those smoking (Newport 100s), drinking, cursing women who, though well-read and college educated, could hold her own in a bar brawl or street fight, a Scrabble game or a Dozens match, against an obnoxious cab driver or a rude hostess at some fashionable restaurant.

A full-figured Jersey Girl/Prince fan/ disco dancer, she was a former Catholic school honor student from Irvington, by way of Newark. Her dad owned a barbershop, her mom operated a soul food restaurant, and she had an elder brother, sixteen years her senior, who turned her onto art and photography. Lesley once dreamed of being a downtown Interview/Details writer like her heroes Stephen Saban, Fran Lebowitz and Michael Musto.

Flannery O'Connor was her favorite short story scribe, a writer that I later embraced, but might not had read without my girlfriend’s encouragement. Lesley got a degree in journalism and publicity from the School of Visual Arts (S.V.A.), Class of ‘88. She reminded me of all the smart, yet unwritten, Black women I imagined sipping Kir Royales in the shadows of Tama Janowitz and Jay McInerney novels.

A month before we met, Lesley had celebrated her 25th birthday. We were both born under the sign of Cancer—an astrological recipe for conflict. Sure enough, a few weeks after our first date, we had our first argument. It was the Friday leading into Labor Day Weekend. She wouldn’t wait for me to get off of work before going to her friend Sheila Jamison’s house in Jersey. At the time I still worked a day job at a downtown homeless shelter, and wouldn’t be getting off until a few hours later than when she left.

Mad, I went off to have drinks with Havelock and drunkenly broke my left foot at the 2nd Avenue bar Nightbirds, where my friend Maggie worked and poured tequila with gusto. Three days later, after finally going to the hospital (escorted by my ex-girlfriend’s new boyfriend), I exited with a massive cast that extended to the knee. Walking with crutches, I crashed at Lesley’s crib that first night, and never left.

The following month we went to see Al Green at The Beacon Theater, where the soul man performed a mixture of secular and sacred songs. Sitting on the end seat, my plastered leg was extended into the aisle. During a stirring gospel number, Green leapt from the stage and began running through the theater as though possessed by the Holy Ghost. Lesley leaned over and whispered, laughing, “Maybe Reverend Green can touch your foot and heal it.”

After the concert we went around the corner to soul food restaurant the Shark Bar. We both ordered vodka and tonics, and for supper, gumbo. The cocktails loosened our tongues and we talked about past romances and the lovers who did us wrong. Lesley told me about an ex who stole her stereo. “When we break-up, promise me you won’t take the record player,” she joked. Though we came close a couple of times, thankfully that break-up never happened.

After the concert we went around the corner to soul food restaurant the Shark Bar. We both ordered vodka and tonics, and for supper, gumbo. The cocktails loosened our tongues and we talked about past romances and the lovers who did us wrong. Lesley told me about an ex who stole her stereo. “When we break-up, promise me you won’t take the record player,” she joked. Though we came close a couple of times, thankfully that break-up never happened.

***

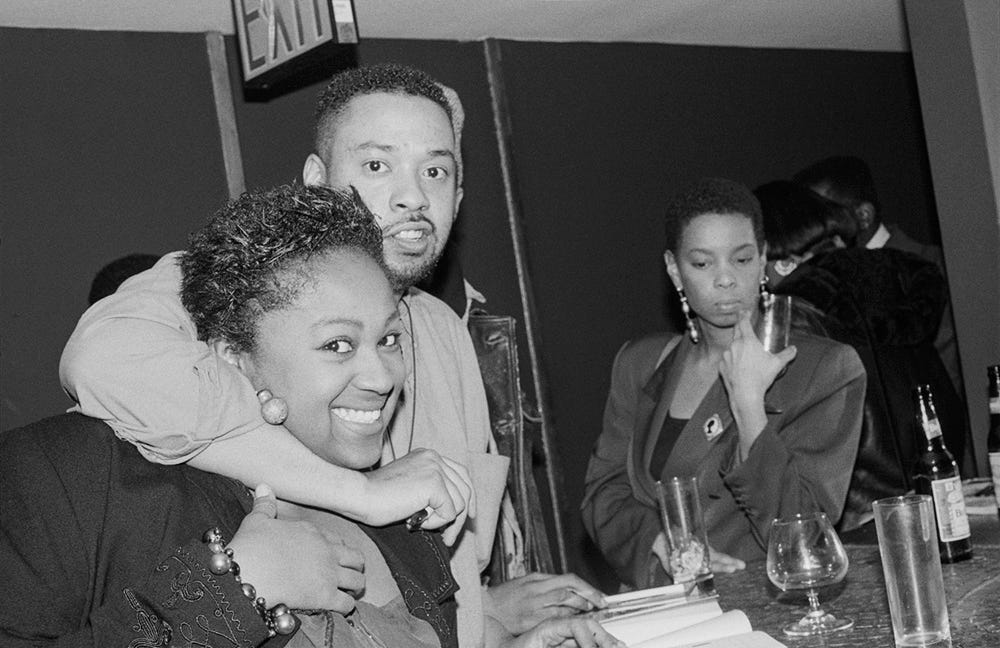

Besides Maggie, who I introduced to Lesley when Nightbirds was our last stop on our first date (Friday, August 16th), Alice was the next to meet my new girlfriend. From that first meeting they liked one another, and soon Lesley was hiring Alice to take publicity photos of her artists, a roster that, over eight years, included Downtown Science, TLC and Jay-Z.

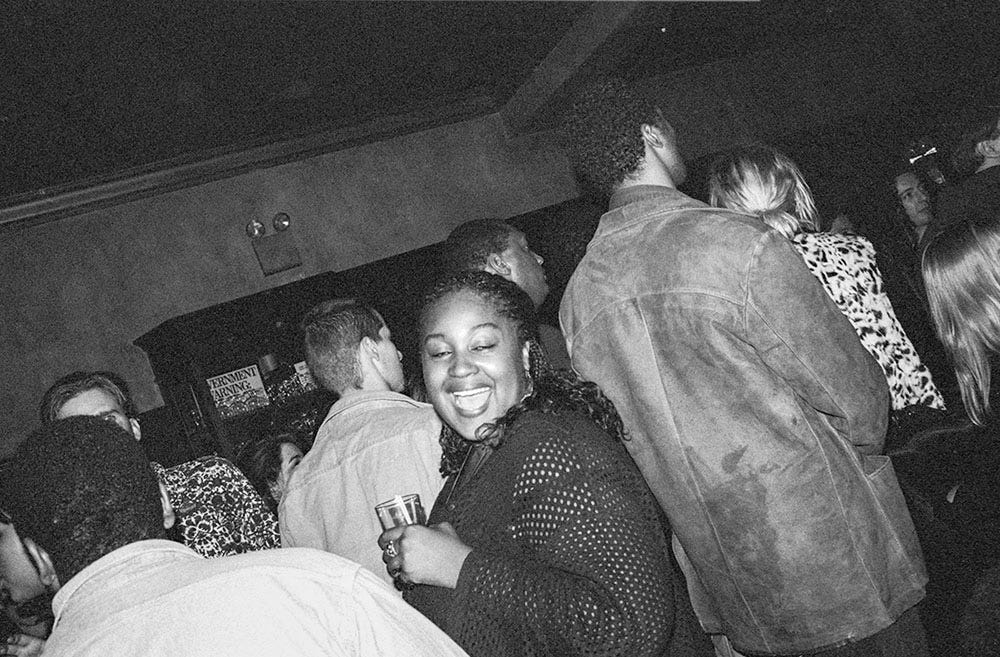

In addition, Alice shot many pictures of Lesley and me, cherished images that became even more special after Lesley’s sudden passing on August 3, 1999 from a brain tumor. Over the years, while digitizing her archives, Alice has forwarded photos of Lesley and me that have brought so many memories to the foreground of my mind.

The first picture we took together was on December 18th, 1991, the night of the Bring the Noise book party at a new SoHo bar/restaurant Sybarite on Wooster Street. In the photo, Lesley, who helped generously with the book’s publicity, looks beautiful with her short haircut and a smile that was beaming, warm as a ray of sunshine on one of the coldest days of the year. It was towards the end of the three-hour event that the picture was snapped. I had low expectations, given how earlier relationships had gone. Nevertheless after our first date on August 16th, I knew that Lesley and I had connected on various levels that included our shared interests in reading, movies, hanging in cool bars, and loving New York City as though we were characters in a bittersweet love story filmed in black and white on the rain-soaked sidewalks of Manhattan.

What brought us together was our mutual ability to riff like Coltrane on various subjects, as demonstrated during brunch at the Pink Tea Cup one Sunday afternoon, when we talked about the lyrics of “Rappers Delight,” the legend of Andy Warhol, the photography of Gordon Parks—who she later worked with on the Great Day in Hip-Hop project for XXL—and the writings of Nettie Jones, whose novel Fish Tales was one of her favorites. Lesley had lost her copy and the book was long out of print. I went on a used bookstore treasure hunt and found it at the Strand. “I can’t believe you,” Lesley said, smiling.

A few years after we moved into a first-floor apartment in Chelsea, I suggested we try to buy a house in pre-gentrified Brooklyn. Lesley laughed. “I didn’t move to New York from Irvington to live in Brooklyn,” she snapped. “We’re staying in the city.”

***

While most of the pictures Alice sent were couple shots, my favorite of the bunch was one she snapped of Lesley alone looking pleasantly intoxicated at Nell’s in 1994, having a blast at a Paper magazine party. Though I’d spent the ‘80s in various dance clubs, including the Garage, Danceteria, Madame Rosa and numerous others, I was far from the black Fred Astire. Lesley, on the other hand, had come of age at Club Zanzibar where the DJ Tony Humphries was known for keeping the crowd moving.

“I’ll give you an A for effort,” Lesley’s friend Sheila Jamison told me one night when a bunch of us danced together at the 1994 Def Jam Xmas party and the DJ mixed Kris Kross’ “Jump” with House of Pain’s “Jump Around,” creating an intoxicating blend.

Over the many years, parties and dance floors in our lives, the one that stands out was an excursion to the Latin club Broadway 96 where we danced as the venue switched between records and a live band. For a few weeks I’d attended salsa classes taught by character actor Paul Calderon, and that night, between sips of Bacardi rum and Coke cocktails, we dipped and spun until last call.

Alice was the next to meet my new girlfriend. From that first meeting they liked one another, and soon Lesley was hiring Alice to take publicity photos of her artists, a roster that, over eight years, included Downtown Science, TLC and Jay-Z. In addition, Alice shot many pictures of Lesley and me, cherished images that became even more special after Lesley’s sudden passing on August 3, 1999 from a brain tumor.

Lesley was a hard worker and was often in the office hours after everyone had left. Thankfully, when we moved to 22nd Street, her job at Jive Records was only three and a half blocks away. There were many mornings when I walked her to the office and some days we’d get breakfast from a diner on 7th Avenue, and eat together in her office until the telephones began to ring.

Friday nights became our date nights. It was the one night a week she actually left work early and joined me for dinner or a movie, getting home in time to watch X-Files and Homicide. Sometimes I brought home peach-flavored champagne that tasted like heaven. Lesley loved it, but joked, “If you tell anyone I was drinking this shit, I’ll have to kill you.”

With both of us working in the music business, there were many industry dinners and open-bar parties, and we drank as much as Nick and Nora Charles from The Thin Man movies. Lesley could drink all night and never look drunk while I was, let’s say, more entertaining. “Just because it’s free doesn’t mean you have to drink it all,” Lesley said one night. I was naturally shy, and drinking, I thought, turned me into a combination of Cole Porter and Superfly spouting Algonquin Table-worthy witticisms.

At parties, she often stood smoking cigarettes, sipping a cocktail and holding court. On the other side of the room with my bushy beard, roaring voice, fondness for flirting, and alcoholic ambitions, I was also puffing on a Newport and holding court. The Thin Man characters Nick and Nora were based on a book by Dashiell Hammett, one of my pulp scribe heroes. He was one of the hard drinking writers whose work I worshipped, alongside John O’Hara, Truman Capote and John Cheever. However, at some point I’d finally realized that their influence had become a problem.

One night in 1999, three months before her sudden death at just 33, Lesley and I watched a TV movie based on Hammett’s life with his girlfriend, fellow writer Lillian Hellman. Played by Sam Shepard and Judy Davis, there was scene in which Hammett was acting like a drunken fool, getting on Hellman’s nerves. I laughed, and Lesley turned her head and glared at me. “See, that’s the problem, you think that behavior is funny. It’s not funny.”

With both of us working in the music business, there were many industry dinners and open-bar parties, and we drank as much as Nick and Nora Charles from The Thin Man movies. Lesley could drink all night and never look drunk while I was, let’s say, more entertaining. “Just because it’s free doesn’t mean you have to drink it all,” Lesley said one night.

On many Saturday nights we lay in bed watching VHS rentals from Evergreen Video, a shop in the Village where every weekend we got four films. While Lesley loved new foreign movies, especially Krzysztof Kieślowski’s trilogy, Three Colours, my tastes ran more towards crime flicks and weird British television shows like The Singing Detective or The Prisoner.

I was also a sucker for dusty film noir and French New Wave, especially François Truffaut, Jean Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Melville. “You like those movies where people talk to much fuck to much, smoke to much and drink lots of coffee,” Lesley teased me. I was mock shocked. “You say that like it’s a bad thing,” I replied.

We always returned the VHS cassettes late, but the store’s one Black clerk, a lanky brother named Reggie, never penalized us. Lesley joked that it must’ve been a form of reparations, but she never knew how right she was. Later, when I got to know Reggie better, I asked what the deal was with him letting us slide. “I never charge Black people penalties,” he said, and we both chuckled.

With the money we saved from late fees, Lesley and I took a few vacations, mostly over Christmas when we went away to resorts in Jamaica or Mexico, escaping the craziness of the states until after the New Year. As a former Black Goth, I’d never been one for sun and beaches, but creeping into my mid-30s I began enjoying the outdoors more and even got a few tans. “I’m only doing this to make people jealous when we go back to New York in January,” I insisted.

***

The days leading up to Lesley’s death were close ones. They began with her comforting me through my Mac crashing and losing a story-in-progress, followed by dinner and martinis that Monday night at Temple Bar. On Tuesday afternoon I canceled a meeting with an editor at The Source to stay home. Between 1 and 4pm that afternoon, we listened to an advance copy of the soon to be released Mary J. Blige album, talked honestly about us, and made out on the green office couch like teenagers.

Lesley’s passing happened so quickly that it still numbs me when I think about it, though I did smile a few years later when I realized she and Flannery O'Connor both died on August 3rd. Sudden death, at least for me, can be hard to process. 25 years after Lesley’s death there are days when I still feel as though I’m mourning, while also celebrating her life in my work.

At 4:10 pm she began complaining of an extreme headache. At 4:30pm she was rushed into the St. Vincent’s Hospital emergency entrance by ambulance. At 5pm she was gone; the headache was a symptom of a pulmonary aneurysm.

Lesley’s passing happened so quickly that it still numbs me when I think about it today. I was 36 when she passed, I'm 61 now, and I'm still just as deeply affected by the loss—though I did smile a few years later when I realized she and Flannery O'Connor both died on August 3rd. Sudden death, at least for me, can be hard to process. 25 years after Lesley’s death there are days when I still feel as though I’m mourning, while also celebrating her life in my work.

***

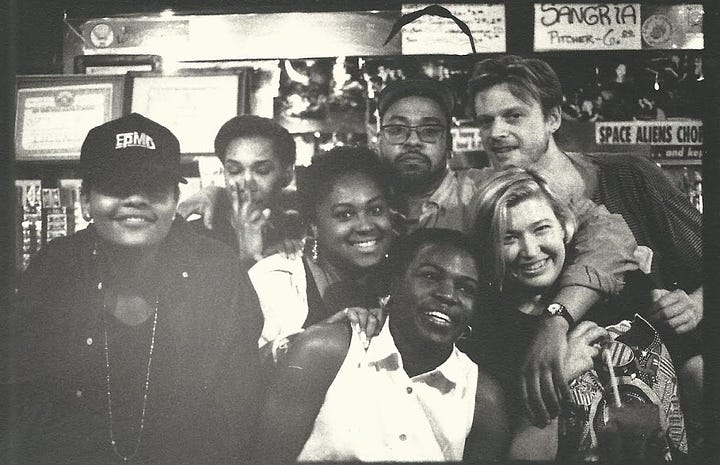

Looking at the few group shot pictures taken at various parties and gatherings reminds me of the many wonderful people who were in our lives throughout the 1990s. Lesley was always popular and her best friends (who soon became my friends too), who included her homegirl Fiona Rose, who she’d “known since Brownies,” fellow publicists Devin Roberson and Sheila Jamison, both of whom worked with Lesley at Set to Run. There were also Audrey Lacatis, Patti Webster, Wendy Washington, Karen Lee, Lisa Cortes, and Marjorie Clarke. Danyel Smith, who was my editor at Vibe, became her tightest girlfriend. They shopped together, drank together, and on Monday nights watched Melrose Place.

Most Thanksgivings Lesley prepared a huge feast, and whichever of our “orphaned” friends were stuck in the city would make their way to our place for a hearty meal. Lesley was a great cook (the oyster stuffing was my favorite), and often talked of food preparation as therapy. As she stood over the stove balancing pots, Aretha Franklin, Donny Hathaway, Chaka Khan, Al Green, and Stevie Wonder served as her soundtrack.

Stevie was her most beloved male vocalist, and she helped make him a favorite of mine too, though I preferred his maudlin ballads, “Tuesday Heartbreak” and “I Never Dreamed You'd Leave in Summer,” to his more upbeat material. Strangely enough, Lesley passed away on a Tuesday in summer, giving rather spooky meaning to those songs.

Twenty-five years later, my memories of Lesley and that first day are as vivid as Alice Arnold’s brilliant photographs. Though I still mourn her premature departure from our world and my life, I’m grateful that many of Lesley’s moments throughout the 1990s were artfully captured in our friend’s pictures.

You are still mourning. It manifests in your loving words and sweet recall. Why stop? She’s part of you.

Very tender and joyous and moving. Thank you, Michael. I'm ready for my Monday now.