How Dance Can Save Your Life

After recovering from breast cancer treatment in her 50s, Martha Bayne reclaims her right to take up space as a dancer.

Two years ago I placed my left hand on the barre and, as the pianist plinked out a 4/4 refrain, sank into a demi plié—something I hadn’t done in thirty years. It was April Fools Day. What better day, I thought, to embarrass myself in public?

I had registered for the class in a fit of frustration with my compromised body. I was 55 and recovering from a year of treatment for breast cancer, the brutal side effects of which had recently been compounded by an improbable broken ankle. The port jutting from my sternum was covered by a long-sleeved t-shirt and my left pectoral muscle pulled and ached at the surgical site, stiff and scarred despite months of gentle therapy. But the seasons were changing: my bones were healing, the exhaustion of radiation and chemo was lifting, and my hair was growing back. I was vibrating to move—and to my surprise, rather than feeling foolish, I felt reborn.

Or, more accurately, not reborn but returned to a sense of self I had believed solidly lost to time.

I don’t remember asking for dance classes as a child—it was just a thing that little girls did, as so many of them still do today. But once I started, I bit down and held on hard, advancing through the levels at Seattle’s Pacific Northwest Ballet School with clockwork precision.

I was 55 and recovering from a year of treatment for breast cancer, the brutal side effects of which had recently been compounded by an improbable broken ankle. The port jutting from my sternum was covered by a long-sleeved t-shirt and my left pectoral muscle pulled and ached at the surgical site, stiff and scarred despite months of gentle therapy. But the seasons were changing: my bones were healing, the exhaustion of radiation and chemo was lifting, and my hair was growing back.

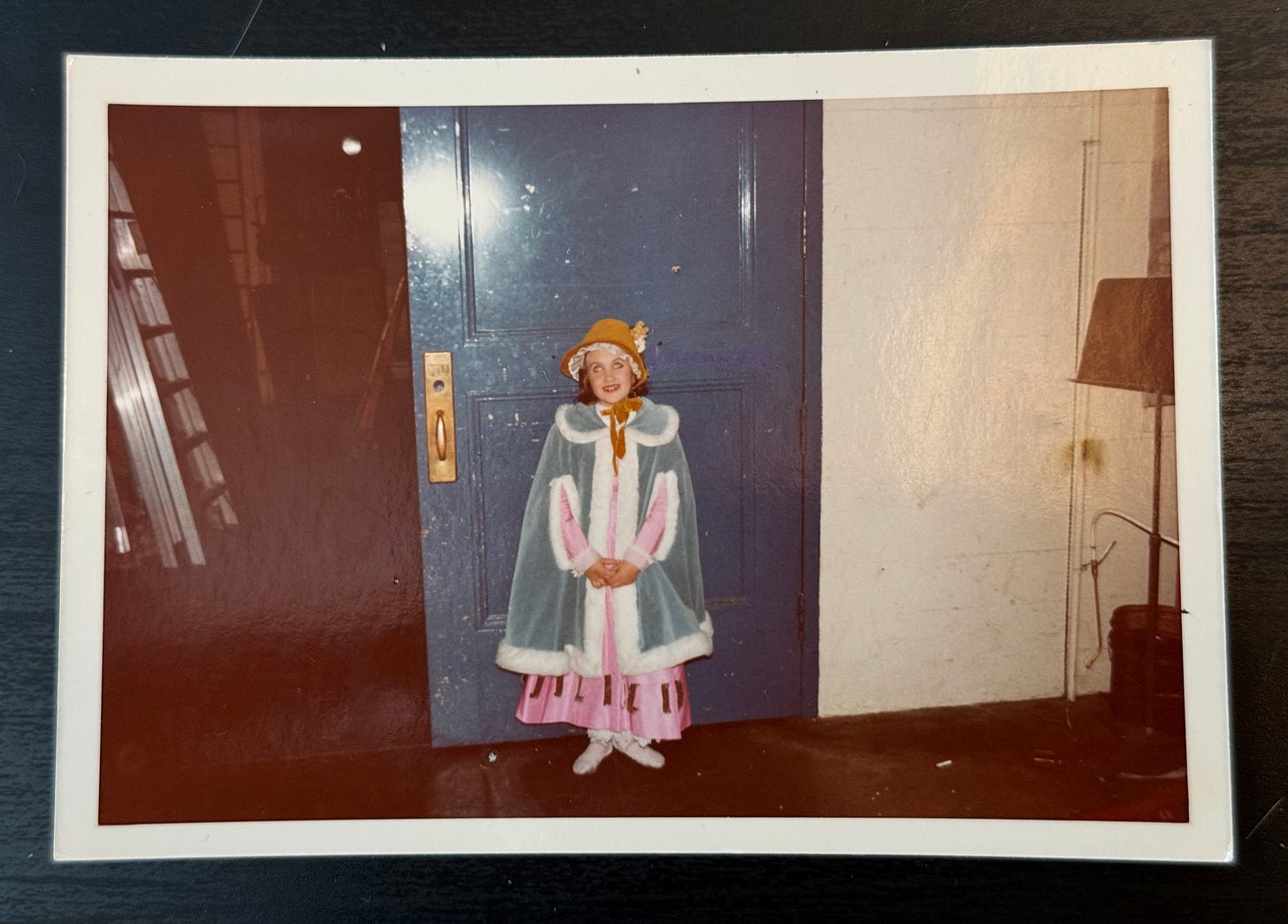

I didn’t understand it then, but looking back I know I responded to the discipline of the training, this space where there were clear rules and what seemed to be comprehensible expectations. Every class started with pliés and moved on to tendus. Learn to pirouette? Swap out your baby blue leotard for lilac and advance to the next class. I was an awkward, authority-pleasing bookworm with glasses and even in elementary school I was fearful of misreading social cues. In ballet, I knew what to do, I was praised when I did it right, and at least in the early years, corrected and encouraged when I didn’t. I rushed to class after school, eager to change into my dance clothes and pin up my hair. I applied myself not just to the physical lessons of ballet but those of its attendant culture. I learned to lacquer my bun with AquaNet, to carry a ludicrously large bag, and to parse the failings of my body with studious attention.

As a professional training school attached to a company, PNB had a Nutcracker full of roles for children, and I performed in it five years running, checking in at the stage door of the Seattle Center Opera House like a boss. First I was a buffoon, the part for the littlest kids, who run out in the middle of the second act from under Mother Goose's skirt to dance around in red pajamas. Later I was given a coveted role in the first act party scene, and I was cast as a toy soldier twice. When I was 13 I was an angel, the role for the tallest girls—the ones who didn't fit into any of the other costumes but were not yet old enough or skilled enough to become apprentices. As angels, we were allowed to take company class on stage before performances, and I thought I had truly died and gone to heaven.

But eventually, like so many young dancers, I developed boobs and hips and an eating disorder, and I left. I don't remember if I was asked to leave, or if I wasn't advanced, or if I just decided at some point that this was going nowhere and I would be better off somewhere else. I followed one of my PNB teachers to a new studio, and I got into modern dance and jazz at another space run by the park district. I went to class off and on through high school, sometimes in secret, even as I was pulled away by the tug of cooler friends and parties and the thrill of the Seattle music scene, then just starting to prove itself exceptional.

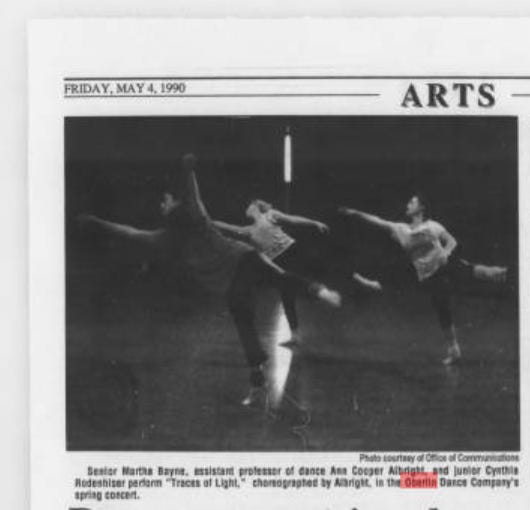

When I went away to college, destabilized, the familiar structure of the dance department kept me grounded. And while I flunked art history that first semester, I kept on going to class. By the time I had finished the requirements for my major, I found myself happily dancing pretty much all the time, perpetually in sweaty tights and warmups. I remember the semester before graduation as one of sudden, immense possibilities. I worked as a TA for my dance advisor, and I danced in her company, a company into which she had cast me not by audition but after watching me dance at the college disco. This astonished me, that such a thing was possible, that I could just dance, and it might make me a dancer.

I don’t remember asking for dance classes as a child—it was just a thing that little girls did, as so many of them still do today. But once I started, I bit down and held on hard, advancing through the levels at Seattle’s Pacific Northwest Ballet School with clockwork precision. I didn’t understand it then, but looking back I know I responded to the discipline of the training, this space where there were clear rules and what seemed to be comprehensible expectations.

Commencement weekend I performed in a student show, and afterward a woman—a parent? an alum?—cornered me to say, with fervor, “Don’t ever stop dancing.” But of course, shortly thereafter, I did. After graduation I went to the American Dance Festival – the birthplace of modern dance—for the summer and studied with Chuck Davis, the legendary master of American African dance, and with the luminous Peggy Baker, a gorgeous modern dancer who worked with Mark Morris and Mikhail Baryshnikov’s White Oak Dance Project. But I was lonely and broke and surrounded by such an abundance of talent that my own efforts at artistry came to seem pointless. For reasons I can’t quite remember, I left ADF a week early to hop a train to New York, where my boyfriend and an entry-level job in the dance world, at the Joyce Theater, were waiting.

For a year I took classes around town, and I performed a bit with friends from ADF in experimental spaces for emerging choreographers. But on my own I was adrift, and I couldn't find my people. Without the anchor of my college community I drifted away, unmoored, and no one appeared to notice. I considered myself a feminist, but felt the best way to manifest that was to prove my worth to men, in their world. My boyfriend was a lighting designer, so eventually I quit my job and followed him to summer stock and learned to be a theatrical electrician, wielding a crescent wrench with pride. Later, I would tour with the company then known as Feld Ballets/NY as part of the crew. From time to time, as we were setting up on the stage in some theater in Milwaukee or Sarasota, I would bust out a pirouette and the other electricians would roll their eyes indulgently, as if to say, silly girl. I watched company class from backstage and wondered what it might feel like to join them, but I didn’t dare.

At the time, none of this felt remarkable. Just one of those things, a childish pursuit now set aside. I stuffed dance in the box marked “over and done,” and didn’t open it for decades. But now that I have, I keep returning to the question of why I quit in the first place.

So much of that moment is lost to time; there was no precipitating event. There are barely any photos! But the strongest feeling I can dredge up is that of shame. Shame that, good but not great, I wasn’t a better dancer. Shame that I had devoted so much of my then-young life to such a marginal and girlish pursuit. Shame that at the time I perceived my entry-level arts administration job—an objectively good job for a 22-year-old who’d been a barista, a bartender, and a college radio DJ—as somehow to be working for the man. I was living in the East Village, seeing shows, staying out late and getting drunk. My peers—mostly men—were getting famous playing in bands. No one cared about dance. It was so deeply uncool, and besides, I had dropped out, I wasn’t that good, and no one forced me to leave. But as I would go on to experience in my romantic life, even though the breakup had been my idea, in its destructive wake I grieved the loss while pretending to the world it was no big deal.

Once I found my way to aerial circus classes a dozen years ago and discovered I was still flexible, I would occasionally tell people, “I used to be a dancer,” if they commented on my lines. But I rarely elaborated, unsure where it fit in the taxonomy of dreams deferred.

I keep returning to the question of why I quit in the first place. The strongest feeling I can dredge up is that of shame. Shame that, good but not great, I wasn’t a better dancer. Shame that I had devoted so much of my then-young life to such a marginal and girlish pursuit. Shame that at the time I perceived my entry-level arts administration job—an objectively good job for a 22-year-old who’d been a barista, a bartender, and a college radio DJ—as somehow to be working for the man.

But aging in general and serious illness in particular have propelled my memory full-throttle back to these formative years. The sense-memory of the ballet studio, the soaring piano, the tang of rosin and hairspray and sweat—it’s all right there. And as my psyche matures, even as the body it’s attached to inevitably degrades, I see how I may have prematurely cut off this beautiful limb to spite the face I thought I needed to wear.

At that first class two years ago I was anxious, but muscle memory is real, and as the barre progressed through tendus and dégagés, I was beyond surprised to discover that mine has apparently merely been dormant, not dead, all these years. I’m not alone. While experimental and postmodern dance has a long history of honoring so-called “nontraditional” dancers, ballet has classically been a young person’s game. But as a recent article in Glamour attests, adult ballet is booming, thanks to the field’s long overdue reckoning with its more toxic, exclusionary aspects.

My classmates run the gamut—some true beginners, still figuring out their limbs; a few former professionals, offering an aspirational model; and a lot of people like me, excavating long-ago training from under layers of sediment, one piqué turn at a time. They are parents and journalists and teachers, retirees and recent college grads. They are my friend Ron, who started dancing at 52 because, he says, “I needed more joy in my life.”

Now 57, I’m taking modern, contemporary, and ballet at several studios around Chicago. My balance wobbles, and I struggle with floorwork, but even as I grapple with my expectations of myself, the ways my body in motion falls short of some youthful ideal, I feel no shame. Thirty-five years out of college, I am again reminded that simply by dancing, I am a dancer. I’m currently in rehearsal for a concert project for “older” dancers, which includes people aged 35-79. And I just completed training to teach ballet and creative movement to cancer patients and survivors like myself. Dancing in community with all these groups, I’m struck by how radical this practice can be beyond the plain measures of personal growth and fitness.

Now 57, I’m taking modern, contemporary, and ballet at several studios around Chicago. My balance wobbles, and I struggle with floorwork, but even as I grapple with my expectations of myself, the ways my body in motion falls short of some youthful ideal, I feel no shame. Thirty-five years out of college, I am again reminded that simply by dancing, I am a dancer. I’m currently in rehearsal for a concert project for “older” dancers, which includes people aged 35-79. And I just completed training to teach ballet and creative movement to cancer patients and survivors like myself.

The act of dancing is essentially analog. It exists solely in the moment, in the body of the dancer, and in the relationship of that body to those in the same shared space. In a cultural and political moment awash in AI and disdain for human creativity, dance offers an experience that is undigitizable and unquantifiable. It offers an opportunity to collectively get out from under the thumb of surveillance, tracking, and the grim deliverables of the current cryptofascist takeover.

For older dancers, ill dancers, LGBTQ dancers, dancers of color, women, and all others whose bodies are under threat from the current regime, the simple act of taking up space carries a heavy weight. When you dance you are celebrating your body’s presence in the world, asserting your right to exist, to take up that space. Embodied, vulnerable, fleeting, dance affirms our humanity. It may have saved my life, and I'm starting to believe it could save the world.

Thanks so much for this piece. I, too, am recovering from cancer (of a different kind) and, having been a musician all my life (something I thought I had to give up and did give up when I was diagnosed in 2018), I am now learning three new unrelated instruments; violin, concertina and hangdrum. Your story has uplifted and inspired me to keep going with the music (I'm 69) by the camaraderie it offers. Knowing someone else is out there picking up where they left off helps me to go forward and not feel so alone. Thank you!

I love this piece. I’m 15 yrs older but had a similar path back in NY in the 80’s. I loved dancing but didn’t think I had it in me so I went back to school to become a physical therapist. I’m still working and specialize in women’s pelvic health but I’m still the dancer. ♥️