Haircut, 2016

Rebecca Moore reflects on what political style statements can (and can’t) achieve.

In December of 2016, I cut off my hair to fight the patriarchy. It didn’t work. I was reeling from the election, from the vision of all those Republican wives who appeared at political events on television, smiling like assassins, dressed to satisfy a particularly invasive male gaze in their tight, impractically pale sheath dresses, every surface buffed and polished.

Neither they nor the men they stood by were calling out the infamous pussy grab; it seemed not to matter. Perhaps they thought they were safe in their youth and good looks. Perhaps accepting it was the price they had paid. They had been found desirable and were safeguarded in private jets and large vehicles in exchange for claiming these men would take care of us all, too. Why were they smiling? Why weren’t they angry, too?

I was turning 50 and I wanted to enter this new decade with dignity and on my own terms. I did not want to cling to some notion of beauty or youth. I got rid of all my uncomfortable shoes and padded, underwire bras. I still remember the thrill of my first heels in middle school, but by the time I had reached an age when it was appropriate to wear them, I didn’t want to. I was going to own 50, not feel diminished by it. I wanted to renounce those particular trappings of femininity that I had attempted, endured, possibly failed at over the years, and embrace whatever I would be in this next phase of my life, this late middle age or early old age or whatever 50 means.

I clipped a recipe from a magazine that I stuck into the clear sleeve of my recipe binder; on the back was a picture of a woman with extremely short hair. I thought I could be her, this woman with a crewcut, but I knew I didn’t have the face to pull it off without looking too severe, like a gawky boy, or worse, a sad old man. I had barely survived two very bad short haircuts, one at 15, the other at 22, but maybe this time would be different. I wanted the sharpness, the angularity, the confidence of shedding vanity. I thought about the weight of everything—the hair, possessions, T-shirts I never wear—but that hold sentimental value, the expectations of performing femininity. I wanted to be free, to take bags of clothing out of the house, and have heavy hanks of hair falling to the floor.

I was turning 50 and I wanted to enter this new decade with dignity and on my own terms. I did not want to cling to some notion of beauty or youth.

It wasn’t a bad haircut, but it wasn’t me. I couldn’t bring myself to go all the way. It wasn’t the cleaner, lighter, fiercer me I had in mind. What I needed was to find my voice. To say, I’m 50 and I still exist because there’s more to existing than being perceived as attractive. We had elected a government that didn’t see us, no matter how attractive we were, as worthy of being heard.

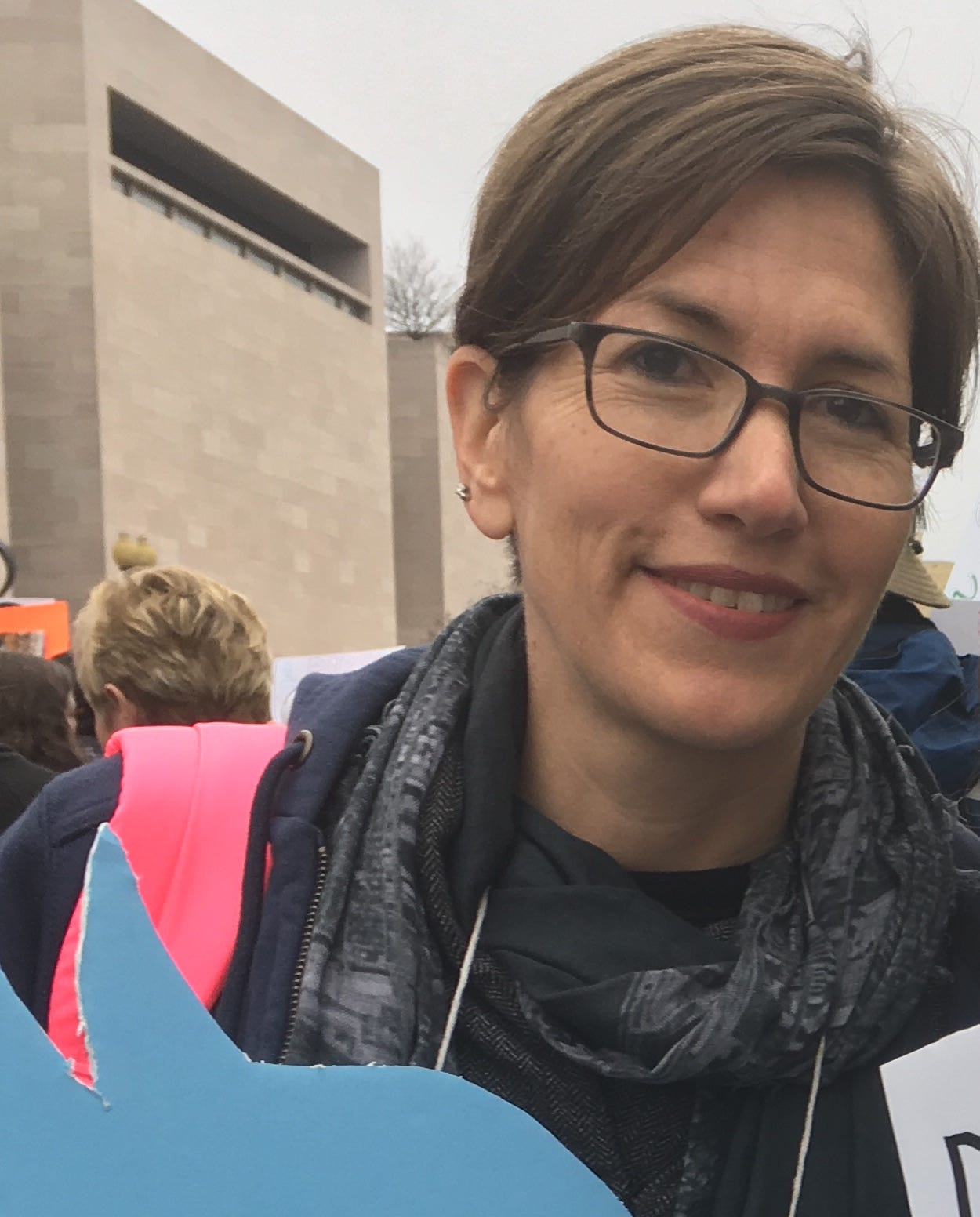

I went to the Women’s March in Washington with my cousin from New Orleans and her friend and our teenage girls, because we had to say something and it seemed we couldn’t say it where I live, in the South, in Alabama. It was a last-minute plan. They had room in the car.

Afterwards, I let my hair grow out. The short hair didn’t define me and neither did the long.

We were all so angry, incredulous, grieving. We bought what could pass as pussy hats at a truck stop near Virginia Tech. They were camo hats with a foliage print and a pink fleece lining. The truck stop also sold key chains that said, “Why don’t you slip into something nice… like unconsciousness.” I took a surreptitious photo of the key chains. We didn’t turn the hats inside out until we were safely in the car.

Turning 50 was okay. It felt good to be at the March—for our daughters to see they had thousands of allies—and sad to come home, back to silence.

Afterwards, I let my hair grow out. The short hair didn’t define me and neither did the long. It wasn’t the appearance of the women on the MAGA podium that mattered most, but the fact that they were up there at all, believing that these awful, sanctimonious men were the right choice for all of us.

Of course it got much worse. On the day in June, 2022 that Roe was overturned, I was home in Hunstville. We went downtown. There were some demonstrators opposite the courthouse, but otherwise people seemed content. Afterward, as we were leaving, we passed a young couple: the woman with a contoured face, in tight jeans, teeters on 5-inch stiletto sandals, while her date saunters along in the comfort of flip flops, Tommy Bahama shirt and baggy shorts, like he has choices and she doesn’t.

Excellent. I can feel the emotion you poured into this post (even if I am a male). I now sport a ponytail tied behind a mostly bald head. Here is a short acknowledgement (in part) of the reason behind the ponytail. I have complained every month, for over forty years, about not getting my money’s worth at the barber shop. With two sides of hair thin enough to see through, going to the barber became a short-lived luxury. By the time I was comfortable in his chair, he chimed, “next.” The pandemic taught me to become self-sufficient and to take my hair’s length into my own hands.

The mirror and I are now best of friends. A snip here, a clump there, a brush stroke or two, and my shiny dome is encased by trimmed sides. Oh yes, I should mention that I am sporting a shoulder-length pony tail.

Such a good reminder of how (and why) we marched in 2016 💕in our pink hats. And such wisdom about women's hair. I have always called them "my Joan of Arc" years when I wore my hair half an inch long: no grooming required, ready for battle, and martyring myself to the cause (over burdened working mother and wife). Now in my 60s, my hair is (finally)it's natural colour and I get a good cut a few times a year. It is not lost on me that the time I take to groom my longish hair now is a statement of self love and care. Of putting myself first, at last🥰