Hair

“Hair was everything to my generation,” 71-year-old Meredith Maran writes, considering here how various tribes use hair to express who they are.

When I lose her, I lose so much hair. That thick, soft hank in my right hand when I drove her, squinting into the sun’s glare, from my Silver Lake bungalow to LAX. That thick, soft hank in my left hand when she drove me, her car’s heater blasting, past blackened snow mounds to O’Hare.

I liked having something of her to hold onto.

As if I actually could.

Hold onto her.

***

Her hair, though. The cool silk sheet of it fanning my writhing, sweat-drenched body. The tickle of her shorthairs stuck between my teeth.

She wanted to touch my hair, too. I almost always said yes to her, but I did refuse her this one thing. My curls, like me, are Semitic, sensitive to seemingly imperceptible shifts in barometric and homoerotic pressure, relationship status, locale. As desperately as my body craves touch, that’s how desperately my frizz-prone curls eschew it. She begged me for a waiver. “They’re not waves. They’re curls,” I punned. She frowned prettily. “I hate puns, remember?” she said.

I liked having something of her to hold onto…As if I actually could…Hold onto her.

Me without puns is like Oxford without commas. But as we went on, I made fewer and fewer of them, consistent with my nonstop apology for being me. Sorry I’m old: 67. Sorry I’m twenty years older than you. Sorry our no-future romance crimps the edges of my lust, my hope, my heart. Sorry I want to go to the movies with you, share a kitchen with you, grow even older with you. But hey—at least I stopped the damn puns.

Now that we’ve excised each other, I wonder, does she miss my wordplay? My rose petals in her mailbox? My untouchable hair?

***

If I seem fixated on hair, please understand: hair was everything to my generation. It’s everything to me still. In the late 1960s, when Amerikkka was an anthill teeming with trails of runaway teenagers carrying our belongings on our backs, our hair was the beacon that lit our way. Headbanded, bandanna’ed, woven through with ribbons and flowers, hair was how we found each other. Hair was how we found ourselves. They called us hippies. We called ourselves freaks. Our hair was the freak flags we let fly.

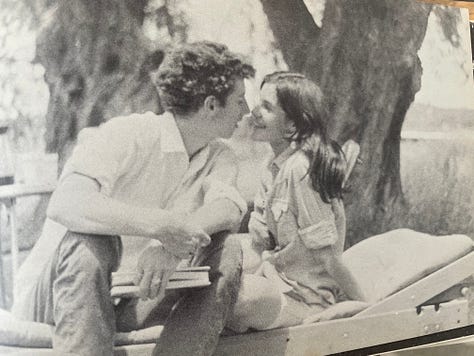

Late one night in ’69 my Dylan-lookalike boyfriend and I pulled our VW bus into Kansas City, hungry and wiped out and broke. We drove around till we spotted some longhairs lounging on a funky city stoop. They pointed us to the local head shop, where the proprietor passed us a joint and a hand-scribbled list of places to crash.

My curls, like me, are Semitic, sensitive to seemingly imperceptible shifts in barometric and homoerotic pressure, relationship status, locale. As desperately as my body craves touch, that’s how desperately my frizz-prone curls eschew it.

Our freak flag was no secret handshake. Our hair was a neon sign visible to all, a recruitment tool for the peace-and-love army. While the adults slept we crept into American cities and suburbs and towns and blew our dog-whistle, Pied Pipers stealing the country’s kids. Our recruits were eager escapees, fed up with their neatly shorn parents, fearful of the futures their country offered them: the corporate cubicle, the Valium marriage—if they survived the draft, the draft dodging, the war.

When we protested outside induction centers, the pigs dragged us into paddy wagons by our hair. Inside, army barbers targeted the longhairs with their psychiatrists’ letters and flat feet and student deferments and viciously shaved their heads.

The Beatles’ first claim to fame? Hair. The black nationalists’ badge of pride? Hair. The Rastafarians’ symbol of strength? Hair. Skinheads’ warning sign? No hair. The endlessly-running, Grammy-and-Tony-award-winning Broadway show of our generation? Hair.

***

In the early 1980s, a decade into trying to stand sex with my husband—closing my eyes to dream him a woman, clenching my fists against his hairy back while his hairy fingers fumbled to find my joy—I went looking for a woman to love. At the lesbian bar, a burly bouncer looked my femme ass up and down and growled, “You’re in the wrong place.” I talked my way inside. As my eyes adjusted to the grainy darkness and my lungs to the smoky air, I realized the bouncer was right. I was in a Hell’s Angels clubhouse, not a wimmin’s bar. The bar was packed with men.

Oh. Wait.

If I seem fixated on hair, please understand: hair was everything to my generation. It’s everything to me still.

The people around me were women who looked like men, in shapeless jeans, plaid flannel shirts, wide leather belts dripping with carabiners, and butchered short hair.

Where were the lean, lipsticked, lingerie-clad, longhaired porn queens of my dreams?

Not in this real-life lesbian bar.

How ironic. Like my 1960s tribe, these wimmin-loving women were waving their freak flags, costumed to broadcast their boycott of the mainstream—the patriarchy and its standards of feminine allure. Like us hippies, these lesbians were uniformed to be recognizable to each other, finding safety in numbers, seeking shelter in a hostile world.

Sociologically fascinating.

Sexually shattering.

Because you know how I am about that one thing.

That one thing I had to have in a lover.

Hair.

***

When first she leaves me, when I’m still belly-crawling thru my aching days, slicking my nightly pillow with tears, I try to find or invent an upside, a story true or false that might impart meaning, if not relief, to my pain.

I tell myself that I’m free, now, to find what I really want, the life-partner she could not, or would not, or, in any case, will not be. Was she what I fear she was, the last wild fuck of my life? Or are all these unwanted steps I’m taking walking me toward the one who’s walking, with sure and steady tenacity, toward me?

Where is she, my next and final lover? What does she look like? How will I know her? Who will she be?

The Beatles’ first claim to fame? Hair. The black nationalists’ badge of pride? Hair. The Rastafarians’ symbol of strength? Hair. Skinheads’ warning sign? No hair. The endlessly-running, Grammy-and-Tony-award-winning Broadway show of our generation? Hair.

In rooms of women, I struggle to quiet my high-beam, search-party eyes. In AA meetings and book events and parties I find plenty to look at and to like. I do what I’ve always done—what I used to do, before her. I reach for this new woman’s eyes with mine, wrap the tentacles of my longings around her, readying to reel her in.

But it’s different now. My gaze gets zero traction. My targets turn their heads to talk to their neighbors, turns the back of their heads toward me. Of course they do. I’m looking at them, seeing possibility. They’re glancing at me and seeing their mothers, if they see me at all.

I remember her telling me, during our first encounter, that our age difference didn’t matter. Later, after her face was tattooed on my heart, she said our age difference was “a lot.”

By which, of course, she meant “too much.”

***

I’ll show her, I decide in a burst of anger. I’ll do what my young lesbian friends are all doing; what I did forty years ago, when I was their age. I take control of what’s on my body, even if I can’t control what’s happening in it. I stop shaving my armpits, my pubes, and my legs. Each day that I don’t shave, don’t make myself smooth and silky and ready for her, is one more day I’m not sitting around waiting for her to realize how wrong she’s been.

In rooms of women, I struggle to quiet my high-beam, search-party eyes. In AA meetings and book events and parties I find plenty to look at and to like. I do what I’ve always done—what I used to do, before her.

For weeks I avoid the mirror, saving myself for the big reveal. On the appointed day I strip and confront my unshaved body. My first glance confirms my worst fear. In the weeks since we parted, I swear I’ve aged a year. When I was hers, I was a fresh, flouncy Easter bonnet. Now I’m a battered, bleached-out straw hat, shoved to the back of the summer closet, out of season, out of time.

I lift my arm, expecting to greet the thick black thatch of my hippie days, the shock of fur that appears whenever a young woman (person) raises her (their) hand in a meeting, or salutes the yoga sun in her late-model Lululemons.

My pits look pretty much the same as they did three weeks ago.

I inspect my unshaved legs. Same.

Holy shit. My body has stopped growing hair.

Live bodies grow hair. Dead bodies don’t.

Am I transitioning from human being to human was?

***

Lonely as fuck on Dyke Day, I ride my bike to the park and stand surveying the scene. Spread out before me, female-appearing humans in rainbow-wear are lounging on technicolor beach towels, their hairy, sweat-shined legs intertwined like pet store-window litters of playful newborn pups.

As I venture onto the field, I run into Courtney, a chic, straight, twenty-something former heroin addict I know from AA. “Everyone’s here,” Courtney says. “Come say hi.” I follow her to a blanket-full of similarly young, hip, straight girls I recognize from the rooms. Why are they here? I wonder. Is L.A.’s Dyke Day more tourist attraction than lesbian jamboree? Just then two long-haired, mini-skirted girls start making out. With each other. Out of the corner of my boggled eye, I catch another pair of chic chicks in an erotic embrace.

WTAF? With their tight little bodies and their stylish little outfits and their stylishly dyed long hair, these girls don’t look like lesbians.

For weeks I avoid the mirror, saving myself for the big reveal. On the appointed day I strip and confront my unshaved body. My first glance confirms my worst fear. In the weeks since we parted, I swear I’ve aged a year.

Maybe, it occurs to me, that’s because they don’t have to.

It’s been thirty-three years, exactly half my lifetime, since I stumbled into a lesbian bar and mistook it for a Hells Angels clubhouse. Apparently, at least in the queer enclave of LaLaLand, today’s young lesbians don’t need to hide, or telegraph, their availability or their identities. They don’t need to costume themselves to hide from hostile straight people, or to be instantly recognizable to other queers. Could it be that with their long and short and wildly hued hair; their unshaven underarms and legs, their rainbow bikinis and designer dresses, they’re costuming themselves for the only reason that humans should: to please and express themselves?

Halleluiah! It’s a revolution in my lifetime. My generation’s risky freak-flag-flying; our love-us-or-leave-us sit-ins and kiss-ins and anguished family-of-origin-comings-out were not for nothing after all. At least in this particular way, in this particular city, on this particular day, the young women of my children and grandchildren’s generation get to be something I’ve not yet allowed myself to be—with my young lover, or with myself.

Proudly, exactly who they are.

I love the fierceness in your writing.

Beautiful piece, Meredith! Hair has been meaningful in my life, too!

In the late 70’s and early 80’s hair was one way punks found each other. I remember my first show and being floored by the variability and creativity- Mohawks and triple Mohawks and hair spikes and every color of the rainbow! It shocked and delighted my teenaged self, driven home by sound that raised my heart rate for the first time!

At underground gothic clubs I fell in love with brooding music and jewel toned velvets and long black hair…and sometimes - with blue-green hair, or white, or deep garnet fire. I loved my own rose red hair, my deep crayon purple hair. (My dad threatened to shave my head but didn’t.) I loved my long white wig. My long black wig. My various hair pins and jewels.

In the Nineties I expressed appreciation for 40’s glamour with glossy black curls, rolls, waves, snoods and flowers. Updos, with fabulous hats. I never fell out of love with that- I’m so glad I got pictures.

Same as you, Meredith, I have loved experiencing the hair of my lovers. The softness and fullness of it. The differences in texture. God save me from hairspray and hair gel. (Whyyy!!!!) The feel of my hand sliding up their nape and splaying to rub the soft stands between my fingers…to massage their scalp and feel them relax. My fingers closing with a gentle twist to bring them in for a kiss.

Hair is connection. You’re only allowed to touch the hair of your closest family and intimates. Dyeing my moms silky fine hair as she aged. I wish i could do it again. Combing and cutting my dads grey strands, which allows me to touch him with care. This is a man I had to teach hello and goodbye hugs and how to say “I love you, too.”

I have LOVED seeing bright unnatural hair colors come back and be done with such flair and beauty!!! It has made me want to put color in my own again, like an old dog that wants to romp with the puppies! D

The thing I didn’t expect was hair loss, which is more common in women than I ever knew. Covid and stress and perhaps all that boxed black hair dye in the middle years! Now I’m trying to treat what I have with loving respect. To buy better product or have it done for me. To lay off the severe pony tails. To consider whether I am too young to let the gray come and stay. (If I did- the bright colors would really show! )

I’m glad my hair is still something I get to play with and that how I choose to as I age continues to be a form of artistic expression.

Thank you for this thoughtful piece, weaving hair into your personal journey of growing up to become yourself. You’ve hit on something. I bet this could be a collaborative book with people sharing pics of them and their hair at various points, explaining what it meant and why it mattered. :)