For Better and For Worse #2: Re(re)thinking "In Sickness and In Health"

When her husband receives a serious diagnosis, Jean Schiffman recalls her father's dedication to her mother, and rethinks what she left out of her wedding vows.

This is the second in a new Oldster Magazine series called “For Better and For Worse.” It features essays and interviews about longstanding relationships. While I know that couplehood isn’t for everyone nor the only way to live, and that it is over-privileged in our culture, I’m interested in how partners navigate their relationships over time. Check out the whole series. -Sari

“77 and 79/You’re still my precious valentine!” wrote my mother in her last love poem to Dad. She was the age I am now, as I write this. In three years, she would be diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. In 15 years, she would be gone.

My parents, virginal and in their 20s, practically strangers to each other but madly in love, got married in a registry office, knowing that in a few days Dad would return to his army unit and be shipped to the South Pacific. In their wedding portrait, Dad, mustachioed, is wearing his army uniform, complete with cap; Mom is in a softly tailored long-sleeved top and a slender belt. They vowed to stay together in sickness and in health, but Mom was thinking beyond that. She always told me that if he died overseas, she wanted to be sure she had a memento—me, born nine months later.

I proposed sensible wedding vows: We’d leave out the “in sickness and health” promise. Why should either of us be tied to a sick partner and sacrifice our own lives? What an old-fashioned, masochistic concept! We’d make no vows we weren’t sure we’d want to keep. He agreed.

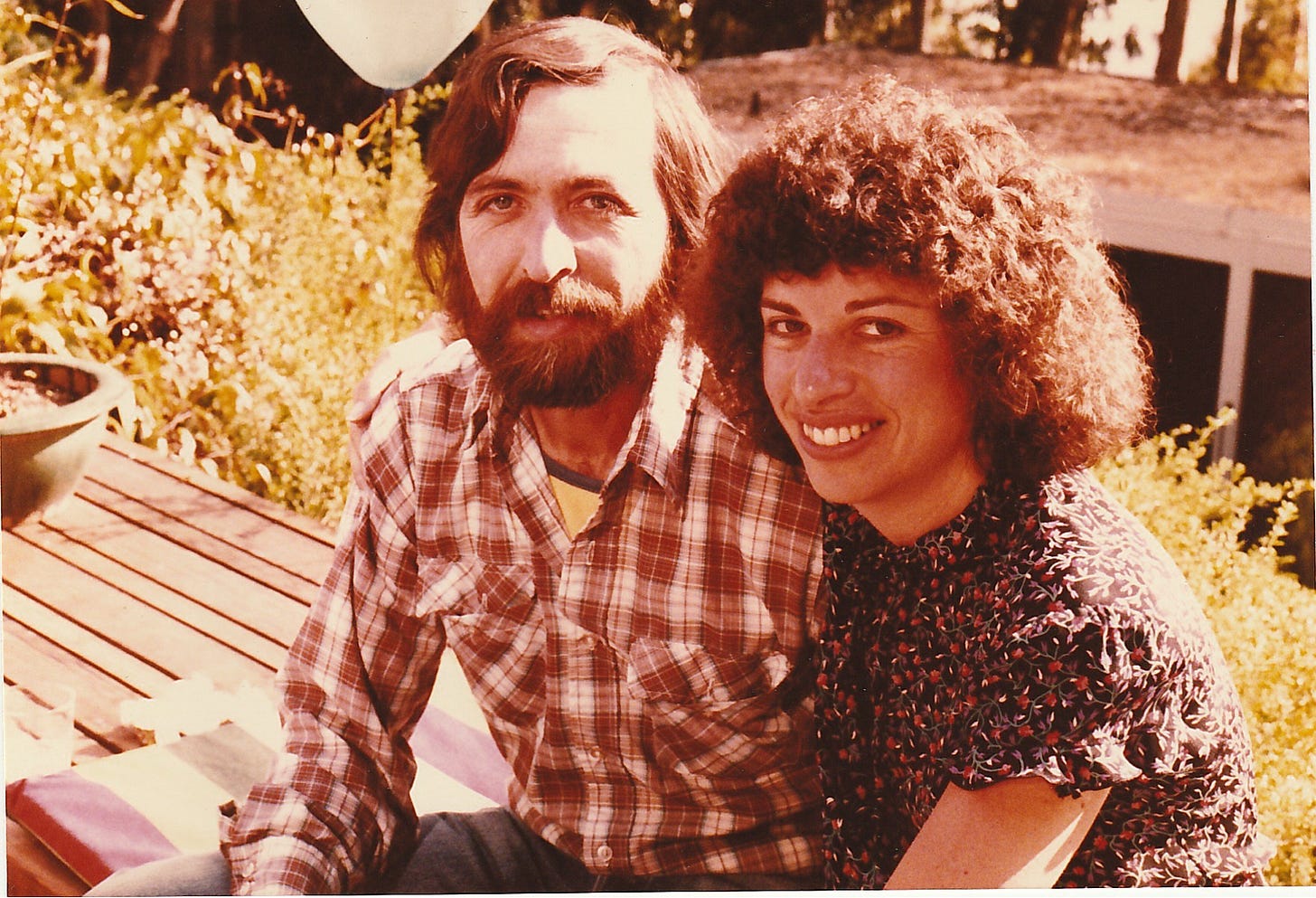

Like theirs, my romance was whirlwind, although modern-style whirlwind. We met in our mid-30s, moved in together after three months, got married at nine months. I proposed sensible wedding vows: We’d leave out the “in sickness and health” promise. Why should either of us be tied to a sick partner and sacrifice our own lives? What an old-fashioned, masochistic concept! We’d make no vows we weren’t sure we’d want to keep. He agreed.

Several years into my mother’s Alzheimer’s, Dad propped that wedding portrait on the mantelpiece, alongside a copy of their marriage certificate. These were handy props for when Mom was being obstinate, insisting they were not married, or were living in sin, or that he was her father, or somebody else’s husband, or she was somebody else’s wife or too young to be married. Sometimes she didn’t know who he was at all. Dad thought documents might set her mind straight. They did not, of course. She scoffed at them. They were meaningless, phony artifacts to her, or simply references to other people.

In that photo, Mom looks more beautiful than I ever remember her looking. Her hair reaches her shoulders, lightly curling, slightly bouffant over her forehead in the style of the mid-1940s. She is wearing a small, brimmed hat. Her cheeks are tinted a light pink. Her eyes, which I know to have been brilliant emerald-green, are large, her face heart-shaped. I asked Dad what color her dress was. He didn’t remember. That unimportant detail, that little fact, was added to the list of Things That I’ll Never Know About Mom.

One day, as Dad sat beside her on the sofa, the photo on his lap, Mom said suddenly, “I know who these people are.” She pointed at herself in the photo. “That’s Jeanie.” She pointed at Dad and said to him, “That’s your . . .”—she hesitated, uncertain—“uncle. Her uncle. No, her brother.” I laughed, but Dad bent over her. “No, that’s you! And that’s me! It’s our wedding picture!”

“Oh, are we married? How nice,” said Mom.

Encouraged, Dad launched into the familiar story of how they met. It was family lore by now, told and retold by Mom over the years and Dad knew that, but for the first time that I can recall, he wanted to tell it himself. Maybe he wanted to be sure I’d never forget it. Maybe he was hoping it would awake for her a beautiful memory. Maybe he just wanted to remind himself.

“I had a summer job at Cedars Resort selling ice cream cones,” he began. “Mom was there on vacation, with her girlfriends. Every day she bought an ice cream cone. She liked me, but I was young-looking for my age, and even though I was two years older than her, she thought I was too young. So she didn’t feel she had to flirt with me or put on airs or be self-conscious. She could just be herself with me, be natural. And I cottoned to her right away. Right away, I thought, There’s someone I could spend the rest of my life with.”

Mom’s friends teased her; they told her he was giving her extra-big ice cream cones. When he told her he’d been drafted, she realized he was older than she’d thought. I think of them, licking rapidly melting ice cream cones under the blistering upstate New York summer sun, Mom so vivacious and chatty, dark red lipstick, maybe in an off-the-shoulder, full-skirted plaid sundress that I’ve seen her wear in old photos, Dad shy and quiet in pants belted absurdly high. Pearl Harbor bombed, Jews murdered in Europe, the world so unsettled. My mother’s divorced, remarried, and recently widowed father (my beloved Grandpa) expecting her to spend the rest of her life taking care of him in his one-bedroom, rent-controlled Brooklyn apartment. Dad, a college dropout. Two naïve kids who didn’t think it was incongruous to get married and have a child in the midst of war.

Mom didn’t pay any attention to Dad’s story; she was yawning and bleary-eyed. But I listened. It was all there, the reassuring foundation of my very existence—the gigantic cones, the girlfriends teasing, Mom just being her natural self with the skinny kid—plus a little extra: He’d “cottoned” to her! He knew right away he could spend the rest of his life with her! Now, content, he led her from the sofa to her bed across the room, by the window.

For many years I thought it would undermine my feminist principles to make any concessions whatsoever for marriage. Yet one of the first things that I, a confirmed city girl, found myself saying to my husband on the day we received the diagnosis was, “When it comes to that, we’ll sell the house and move to a rural area, get away from traffic and crime and noise. You’ll be happier there.”

And, watching as he closed the curtains and gently covered her with a blanket, I thought of my own marriage. About 10 years in, my husband was diagnosed with atrophy of the optic nerve in both eyes, an incurable, progressive, occasionally hereditary condition that ran in his family, throughout three generations—a rare condition, unlike Alzheimer’s, the more common, equally incurable and perhaps hereditary condition that so surprisingly appeared in my family. My husband’s father was legally blind by 50.

I’ve never been good at compromising. For many years I thought it would undermine my feminist principles to make any concessions whatsoever for marriage. Yet one of the first things that I, a confirmed city girl, found myself saying to my husband on the day we received the diagnosis was, “When it comes to that, we’ll sell the house and move to a rural area, get away from traffic and crime and noise. You’ll be happier there.” I actually found myself looking forward to someday being a small town old lady. On the porch, reading aloud to my husband, while he sits in a rocking chair and knits, which is what his father used to do.

Whatever happens, whether my husband ends up with a white cane and a German shepherd, lung cancer or emphysema (the smoker’s diseases), or something else entirely that I can’t imagine, I learned that day of his diagnosis that I won’t be calling upon the escape clause in our marriage agreement, the clause that I was so pleased with myself for crafting.

But that’s the only thing I’m sure of. So many things have turned out differently from the way I expected, right down to Dad’s decline, which so closely followed and in certain ways paralleled Mom’s. I couldn’t have guessed, on my own wedding day, that my parents’ “in sickness and in health” vows would be handed down to me.

Even the noble rocking-chair-on-a-porch scenario was completely wrong-headed. (Who’d be driving to the general store five miles away instead of walking down to Safeway on the corner? Me with cataracts? What would I do without the library a few blocks away? Why would we leave our friends, our support system, Peet’s coffee, back here in the city? What was I thinking?)

Whatever happens, whether my husband ends up with a white cane and a German shepherd, lung cancer or emphysema (the smoker’s diseases), or something else entirely that I can’t imagine, I learned that day of his diagnosis that I won’t be calling upon the escape clause in our marriage agreement, the clause that I was so pleased with myself for crafting.

By the way Dad kissed Mom affectionately whenever she exclaimed, “Oh, are we married? How nice!” I can guess that he had no regrets—or at least none he’d ever admit to a daughter. I can only hope that if I inherit her condition, that my husband—and this is the very first time I’ve ever thought of his side of it—will also have no regrets.

If our lives turn out to be a black comedy, of course, he’ll be sitting at the window in dark glasses, knitting needles clacking, not seeing me down below, wandering the city sidewalk barefoot in my nightgown, my hair like the bride of Frankenstein. In that case, all bets are off.

Beautiful, Jean. I also left out "in sickness and in health" from our wedding vows. Like you, that has all changed. I get why those words matter. They are essential. Thank you for this lovely writing.

Oh Jean, I’m so sorry. But the only part of that “boilerplate” worth remembering is “from this day forward”.

At the end of my first Cancer Care grief counseling session, Lucia my much younger mentor wisely counseled “you can’t defeat nature”. I found that remarkably comforting. I hope you do too.