Debuting at 70

Ruth Bonapace on what it took to publish her first novel as a newly minted septuagenarian.

When the host of my debut book party, teacher Susan Shapiro, asked if she could reveal my age to the crowd, I found myself panic-stricken.

I’d just turned 70. Did I really want to announce my age to a roomful of strangers?

I considered the wrenching possibilities: a younger crowd dismissive of the “Boomer” thrust among them, or agents scouting for emerging talent for “30 under 30” lists. But, grateful to be part of Shapiro’s popular showcase, reluctantly, I agreed.

A bookish kid who wrote poetry and started a school newspaper in middle school, I’d always dreamed of writing a novel. Although most of the authors on our summer reading lists were men, I devoured books by Louisa May Alcott, Emily Bronte, and George Eliot, who used a man’s name to make it in the literary world.

When the Beatles released “Paperback Writer” in May 1966, I plunked quarters into the jukebox at the Catskills resort where my working-class family vacationed each summer. I decided I’d write a dirty story about a dirty man if it led to a book.

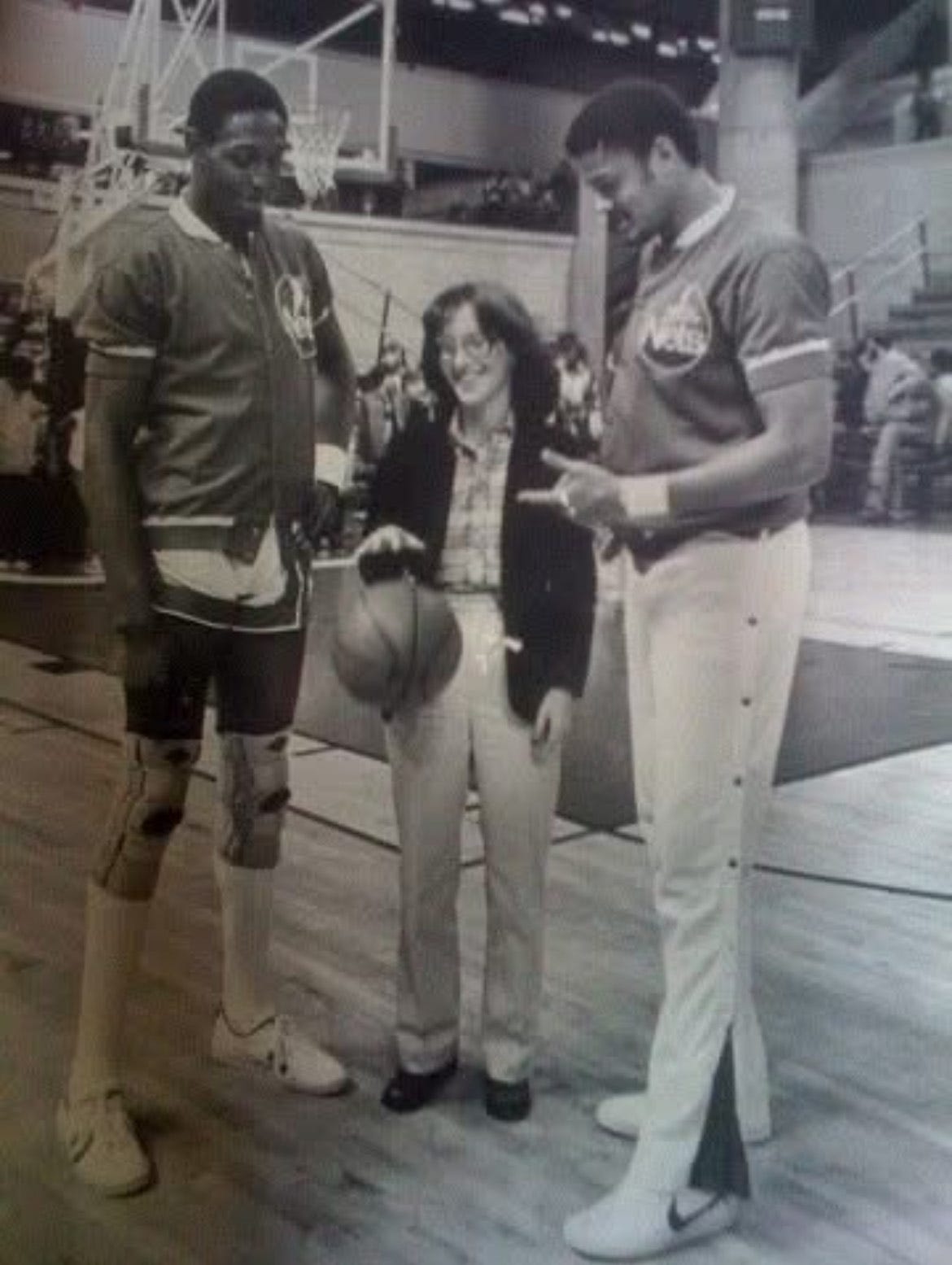

In college, I turned down law school for journalism. I wanted to chronicle everything, from eccentric characters to politics, and I did, including pro sports for The Associated Press. While I was adept at churning out news stories, I marveled at colleagues who parlayed their newspaper beats into books. I hadn’t the slightest idea how.

At 30, fresh off covering The World Cup finals in Spain, I had my first child Lisa, and two years later, my son Dan. Barely managing work and childcare, I put my literary aspirations on hold. When they were finally in school, with my marriage unraveling, I joined a writers’ group in Brooklyn, craving a creative focus more than ever.

My teacher in the 90s, Rick Moody, had an MFA from Columbia, a best-seller, and a movie deal in the works. I had a bachelor’s from a state school and carpools. Still, on office lunch breaks, when the children were asleep, or wherever I had a laptop without interruptions, I let my imagination fly, banging out paragraphs that became a 300-page manuscript. I was exhilarated, but knew it was a hot mess, not ready for publication, and the pages stayed in my desk drawer.

The teacher, Rick Moody—in the early ‘90s still an unknown novelist—gave us a prompt: pick a classified ad and create a short story. As a journalist, I froze. Could I invent a story? As the weeks and months passed, it became easier. When Moody’s breakout book The Ice Storm was launched, he snuck me into his book party at George Plimpton’s Manhattan brownstone. The scene was a childhood dream.

But Moody had an MFA from Columbia, a best-seller, and a movie deal in the works. I had a bachelor’s from a state school and carpools. Still, on office lunch breaks, when the children were asleep, or wherever I had a laptop without interruptions, I let my imagination fly, banging out paragraphs that became a 300-page manuscript. I was exhilarated, but knew it was a hot mess, not ready for publication, and the pages stayed in my desk drawer.

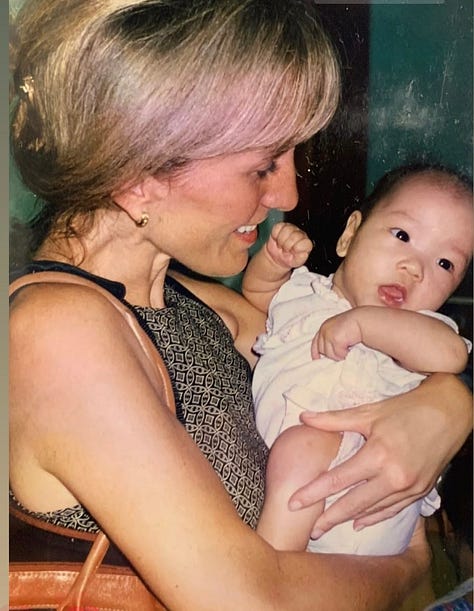

In 2001, when I was 47 and on the cusp of being an empty nester, I adopted a third child, Isabella, from an orphanage in Hanoi. I’d always wanted another child, and I was overjoyed. I never gave up on my dream of publishing a novel. I just didn’t see how, until at an alumni event, a professor told me about part-time studies that might fit with my work and family life.

I had looked into to graduate creative writing programs in the 90s, and again in 2004 and 2005, when my mother was diagnosed with terminal lung cancer. Dad, bereft, fell into a depression and began to decline. I was on the phone daily with caregivers, drove almost two hours to his house weekly, and slogged through the arduous court process to be appointed his guardian, handling all the bills.

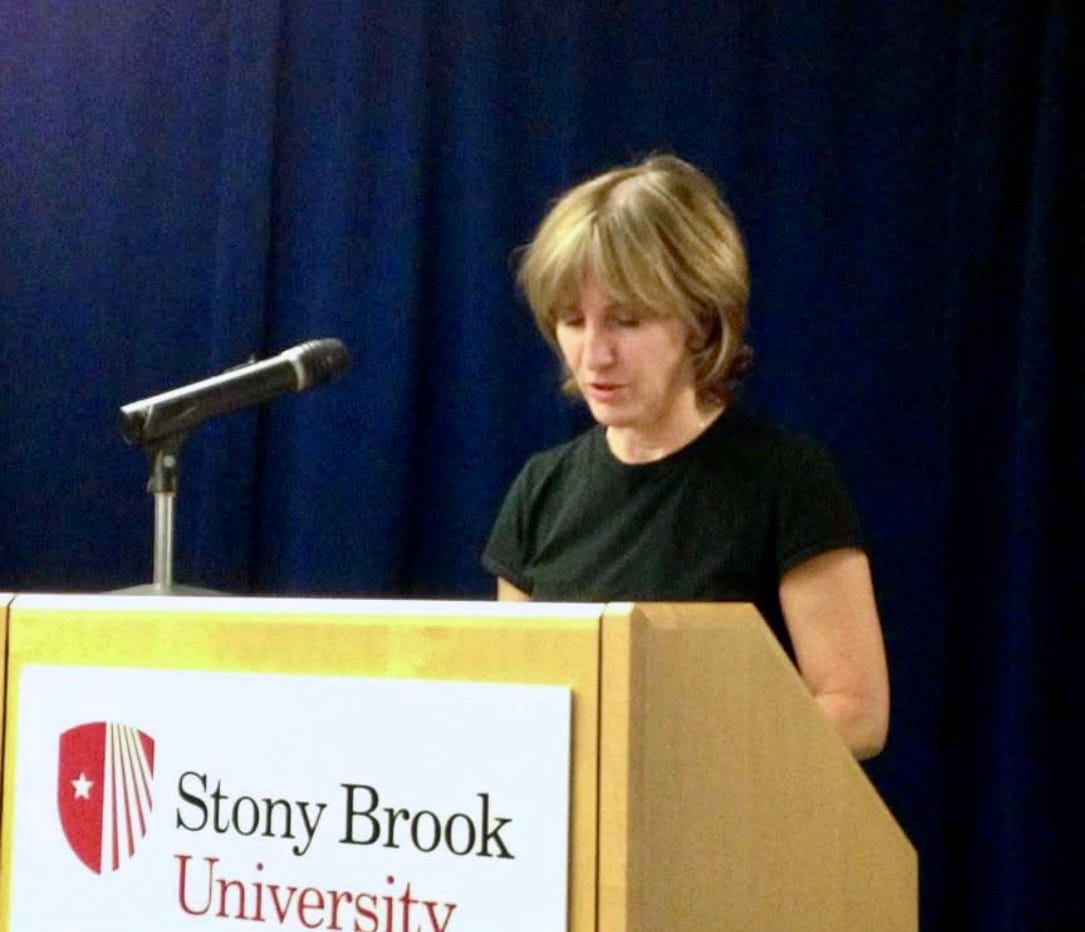

In 2010, I was accepted into a new state university MFA program modeled for mid-career adults, and took classes part time. Isabella was 9 and enjoyed visiting the campus with me. My older two were out of college and on their own.

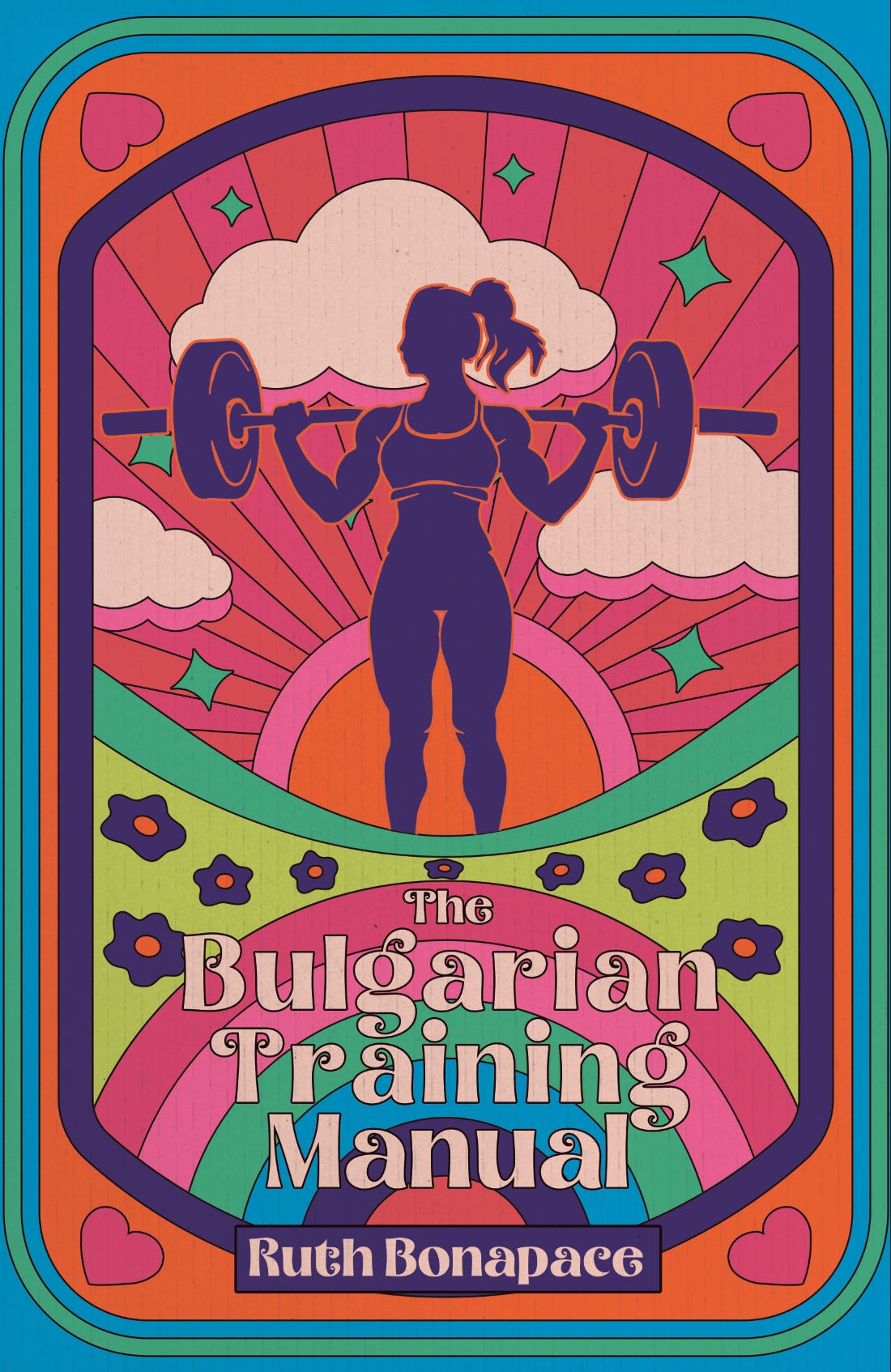

My father listened attentively as I described my courses, and it lifted his spirits. Dad said he hoped it would lead to a teaching career. I had other plans. My thesis was the basis for a new novel, The Bulgarian Training Manual, and this time I knew it was worthy of publication.

But Dad never got to see me realize my dream. He died before my graduation, seven years after I’d enrolled.

While polishing my novel, I tackled the care of my mentally disabled brother, who’d lived with my parents all his life. Digging into my savings, I scoured listings and moved him into a small apartment in an over-55 community with a pet dog to keep him company.

At my book party thirty years later, when I said a halting “yes” to revealing my age, I held my breath. Instead of the awkward silence I’d expected, I heard a swell of applause. A woman I’d never met told me I’d given her hope. “I’m 53,” she said. “I was ready to give up, but now I’ve got to keep going.” A writer in her 80s who’d just sent her memoir to an agent whispered, “It’s never too late.”

In March 2020, with my brother settled, I thought I’d be able to focus again on my dream of publishing my novel. Then the pandemic hit. My manuscript stayed in my laptop’s equivalent of a desk drawer for almost two years before I resumed submissions and got the call—Clash Books, a small press, offered a book deal. The enthusiastic editors were the age I’d been at Moody’s party in New York City, when I was feeling over the hill at 40.

At my own book party thirty years later, when I said a halting “yes” to revealing my age, I held my breath. Instead of the awkward silence I’d expected, I heard a swell of applause.

A woman I’d never met told me I’d given her hope. “I’m 53,” she said. “I was ready to give up, but now I’ve got to keep going.” A writer in her 80s who’d just sent her memoir to an agent whispered, “It’s never too late.” My daughter hugged me with a new baby in her arms. “I’m so proud of you,” she gushed.

To my surprise, the copies of my book on hand sold out that night. I wish Dad could have been there, but thankfully my kids were. And maybe they, too, will know that no matter what gets thrown in their way, they needn’t abandon their dreams. And the next time someone asks my age, I’ll respond proudly, “Just turned 70. Imagine that.” Because at one time, I couldn’t.

Congratulations, Ruth. I’d wanted to be a writer from the age of 13. I published my book last October at age 72. Never too late.

Thank you! This 64 year old is currently querying to agents for my caregiver memoir. You helped me persevere one more month.