What Good Are Our Memories If We Never Share Them?

Esther Cohen considers the importance of preserving the experiences we recall, by writing them down and sharing them.

“We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” - Joan Didion

At a certain point, an indefinite time when you find that you are No Longer Young, memory becomes more important than it was, and almost all of a sudden, at 50 say, or 60, there you are thinking about what you remember. For me, it’s those summers so many years ago.

My summers were spent in Woodmont, Connecticut, on the Jewish beach adjacent to the Italian one. Woodmont was about half an hour from Ansonia, where I lived the rest of the year. Even so, we moved there completely on the last day of school. And we spent every single summer there all the years I lived at home.

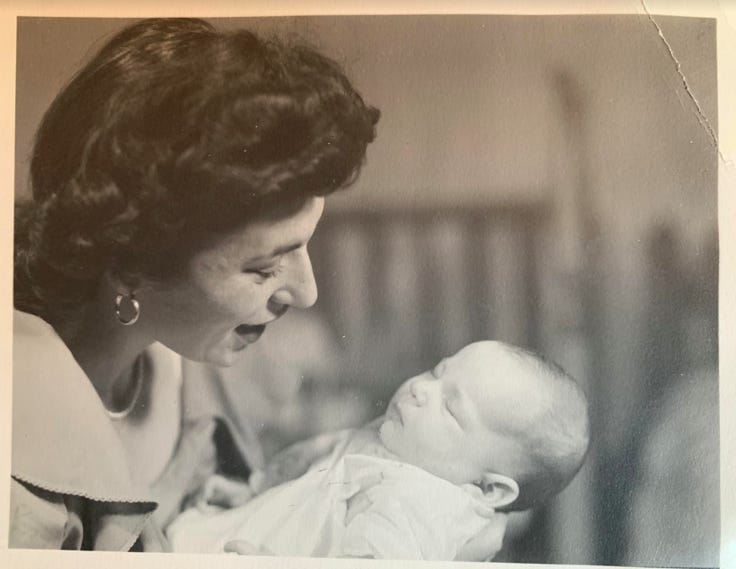

We had the house because my father, 38 when I was born—considered old for having a first child—my father and his college roommate Solly Stein, whose two children were nine and ten years older, decided they would buy a large, ramshackle beach house with green shingles in two adjacent parts, on top of an imperfect seawall above a beach full of rocks and not much sand on the Long Island sound. A beach I’ve never loved more.

I’ve always believed as an ideology, as a religion, as an absolute truth, that we should, every single one of us, tell our own stories.

I’m telling you this because I’ve always believed as an ideology, as a religion, as an absolute truth, that we should, every single one of us, tell our own stories.

Who we are is where we come from and what we’ve seen and what we’ve said. And what we continue to say. And for so many good reasons, it’s a good idea to write it all down. While you remember, and while you can. Life is always in the particular details, the details that only you actually know.

And words can change things: perceptions and feelings and what we believe.

Donald Hall told this story once about his favorite aunt, a single woman whom he loved completely. When she died at an old age it was up to him to clean out her house. He never realized how intensely she held onto every single thing and by the time he reached the attic, he couldn’t believe he’d loved her all those years. How could she have held onto every single thing? He wished he knew why. In the attic, as he was putting her things into big black garbage bags, he found a small matchbox, carefully labeled in her familiar hand: String Too Short to Save. With string inside, of course. And then he loved her again.

People who write, professionally or not, always wonder who they’re writing for. Is there an audience? And how do you find them?

The first question is almost always where to begin. As though there were just one beginning: Long ago on a porch on a farm in a familiar town in Vermont. Or in Minsk. Or on a staircase in a building where every single apartment was still rent-controlled.

Your first audience is always yourself. You write because it’s a good idea, because you’ve wanted to forever, because memory becomes more real when you are able to capture even the smallest piece of a story. You write because maybe there will be a reader or two. Maybe not. You write not to use your piece to get you anywhere, but because you’ve lived a life, or because you haven’t. Because you are old enough now to have so many stories to tell.

And as for the story—it’s often just practice. The same way, as children, when we were taking piano lessons, we’d have to practice with Czerny. We practice putting words onto a paper, or a laptop, or into any notebook.

The first question is almost always where to begin. As though there were just one beginning: Long ago on a porch on a farm in a familiar town in Vermont. Or in Minsk. Or on a staircase in a building where every single apartment was still rent-controlled.

Sometimes I like to begin, when I tell my own story, with my favorite grandmother, Anna Sorocor, a fabulist with a fantastic nose, large and strong. She was a young Jewish girl from a middle class family in a town in Romania called Bacau. She lived an innocent life, and one day, so she told me, when she had just turned 16, she was standing in line in her uncle’s bank. Of course it wasn’t a bank exactly. More like a money lending room. She was wearing a pink and white dress.

You write not to use your piece to get you anywhere, but because you’ve lived a life, or because you haven’t. Because you are old enough now to have so many stories to tell.

Anna Sorocor had spectacular skin. She’d make facial masks with egg whites all her life. And she was as beautiful as every 16-year-old girl. In front of her stood a man with dark, dark eyes. Twelve years older than she was. His name was Shmuel Markowitz. He turned around and said to her: “Come with me to America.” And she, because she’d never felt her heart beat in that very way before, she said, “Yes.”

You left me wanting more! And I’m not ashamed that I own some Talbot sweaters…

I love this piece. Of course, I wanted it to be longer and more about you......And I myself get stuck on the audience issue.