You Don’t Own Me: On Screenwriter & Novelist Eleanor Perry

A retrospective and appreciation.

In the early 1960s, former mystery novelist Eleanor Perry—who co-wrote four crime novels with her first husband two decades before—reinvented herself as a screenwriter and went on write scripts for a few provocative films that helped usher in “The New Hollywood.” Encouraged by her new husband Frank Perry, who she married in 1960, to switch disciplines so they could work as a team, Eleanor scripted the groundbreaking films David and Lisa (1962), The Swimmer (1968) and Diary of a Mad Housewife (1970). At 48 years-old she began breaking barriers while contributing to a changing cinematic landscape; Frank served as resident auteur on those projects, as well as three others. Still, I don’t believe any of their films are as celebrated today to the degree that they should be. This is my attempt to rectify that.

Even so, in recent years movie critics, including Matt Zoller Seitz and Paula Mejia, have revisited their work, and in 2017, there were retrospectives at New York’s Quad Theatre and Los Angeles’ New Beverly. Having seen most of the Perrys’ films, I’ve noted a strange, dreamy quality that they share, and an urban/suburban creepiness that is as theatrical and novelistic as it is cinematic.

In the early 1960s, former mystery novelist Eleanor Perry—who co-wrote four crime novels with her first husband two decades before—reinvented herself as a screenwriter and went on write scripts for a few of provocative films that helped usher in “The New Hollywood.”

The low-budget and independently made David and Lisa was very different from the types of films the studios were producing in 1962. “Based on Dr. Theodore Isaac Rubin's novel Lisa and David,” the New York Times reported, “the widely acclaimed film told the story of two emotionally disturbed teen-agers, played by Keir Dullea and Janet Margolin, who meet as patients in a private psychiatric school.”

The Perrys’ “small” feature had a lot in common with the French New Wave and work by emerging renegades John Cassavetes, Shirley Clarke and Michael Roemer. Surprisingly, the couple received Oscar nominations for David and Lisa (best adapted screenplay and best director) and for the next eight years they worked together on various film and television projects.

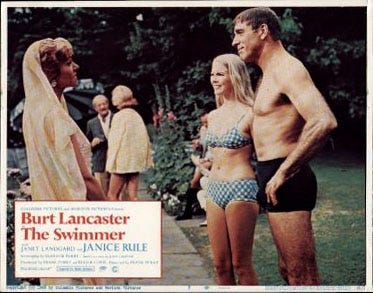

While there were other women screenwriters, including my favorites Leigh Brackett and Ida Lupino, none were as tapped into the changing consciousness as Perry. The couple stayed indie on their follow-up film Ladybug Ladybug (1963), but for their third feature The Swimmer, based on a brilliant New Yorker short story by John Cheever, they signed with notorious producer Sam Spiegel. As the money man behind The African Queen (1951) and On the Waterfront (1954), Spiegel had a reputation for being ruthless and mean.

Eleanor and Frank had no idea what they were signing on for, but it soon became as clear as a glass of gin and tonic. They fought often with the overbearing producer, who changed their script, replaced actors, and fired Frank, replacing him with Sydney Pollack. In the book Sam Spiegel, author Natasha Fraser-Cavassoni wrote that he thought more of Eleanor than he did Frank. “The writer was considered to be more brilliant than the husband.”

In 2023 film historian Eloise Ross wrote in a Senses of Cinema essay, “The Swimmer is also fascinating as an illustration of Eleanor Perry’s distinctive perspective. Eleanor had, early in her career, earned a master’s degree in psychiatric social work and had written various plays that explored mental health issues and other related subjects, notably for the Cleveland Mental Hygiene Association.”

Today the film could be seen as one of the inspirations behind The Ice Storm (1997), based on Rick Moody’s 1994 novel, and Mad Men, but the Perrys hated the final version of The Swimmer, and Frank vowed to never again relinquish control of their projects.

***

Eleanor Perry was born in Cleveland in 1914 as Eleanor Rosenfeld. She married lawyer/playwright/novelist Leo G. Bayer in 1937, and they were together for 21 years. Leo and Eleanor were also collaborators, writing mystery novels under the pen name Oliver Weld Bayer. Their books Paper Chase (1943), No Little Enemy (1944), An Eye for an Eye (1945) and Brutal Question (1947) were published by Doubleday.

Paper Chase was made into the feature Dangerous Partners in 1945, but neither writer contributed to the screenplay. “The Bayers” had two children, William and Ana; both would also become writers. The couple’s full-length play Third Best Sport was presented on Broadway by the Theatre Guild in 1958. Frank Perry was the stage manager, which was how he and Eleanor met. A few months later, she and Leo divorced. A decade later The Swimmer, the film I consider to be among her top three, emerged.

Encouraged by her new husband Frank Perry, who she married in 1960, to switch disciplines so they could work as a team, Eleanor scripted the groundbreaking films David and Lisa (1962), The Swimmer (1968) and Diary of a Mad Housewife (1970). At 48 years-old she began breaking barriers while contributing to a changing cinematic landscape; Frank served as resident auteur on those projects, as well as three others. Still, I don’t believe any of their films are as celebrated today to the degree that they should be. This is my attempt to rectify that.

Two years after The Swimmer, Eleanor and Frank adapted Diary of a Mad Housewife (1970) from Sue Kaufman’s novel, published three years before. It was their most successful feature, but until recently was a film I’d read about, but never seen. A few years back it finally began streaming. In 2021, when it was on the Criterion Channel, New Yorker critic Richard Brody described the relationships-in-ruins drama as, “A horror story about the agonies that a woman endures at the hands of men, in marriage and adultery alike.”

The couple became aware of the Kaufman novel when Eleanor reviewed it for Life magazine in 1967. A year later they bought the rights and the script was written at their East Hampton residence while Frank edited their teen drama, Last Summer (1969). Housewife… shows the “mad” (as in both angry and on the edge of a breakdown) housewife Tina Balser (played with smoldering intensity by Carrie Snodgress) dealing with her selfish, arrogant banker husband Jonathan (a smarmy Richard Benjamin) and egotistical, self-important and thin-skinned novelist lover George Prager (a dashing Frank Langella in his screen debut) and two troublesome daughters.

Critic Richard Schickel reviewed the film for Life in 1970: “Tina may be easily frightened, but however frazzled she becomes, she gives us cause for hope…she’s lovely and complicated and funny and so is the movie they’ve made about her.” Diary was made in NYC and featured scenes of Tina and Jonathan—dining at Elaine’s, where the waiter belittles the social climbing husband, and later drifting through a downtown loft party, where the Alice Cooper band is blaring electric noise.

Eleanor and Frank had no idea what they were signing on for, but it soon became as clear as a glass of gin and tonic. They fought often with the overbearing producer, who changed their script, replaced actors, and fired Frank, replacing him with Sydney Pollack. In the book Sam Spiegel, author Natasha Fraser-Cavassoni wrote that he thought more of Eleanor than he did Frank. “The writer was considered to be more brilliant than the husband.”

Diary of a Mad Housewife was also Eleanor and Frank’s last collaboration. “I hate to say that I’m living a cliché,” Eleanor told Good Day Pittsburgh host Eleanor Schano in 1979, “but maybe when we were poor and struggling we were more happy than when we were successful.” They divorced in 1971.

In the 2021 book Always Crashing in The Same Car: On Art, Crisis, and Los Angeles, California author Matthew Specktor wrote: “Eleanor and Frank were preparing a follow-up to Diary of a Mad Housewife, (with) a picture called Expensive People based on a Joyce Carol Oates novel. But instead, Frank peeled off to make Play It as It Lays (based on Joan Didion’s second novel) alone. Eleanor found out when she bumped into Joan Didion’s brother-in-law, Dominick Dunne, and he told her Frank was in LA scouting locations. According to her divorce deposition taken in May 1971, Eleanor had thought her husband was out finishing their deal to do Expensive People. She certainly didn’t know he’d already committed to Play It as It Lays, or that he was sleeping with someone else as well.

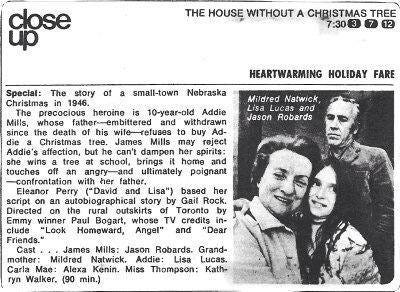

While I’m a fan of the Perrys’ work as a duo, it was Eleanor’s post-divorce project that introduced me to her writing: the teleplay for the 1972 holiday movie The House Without a Christmas Tree. I recall watching that maudlin CBS special when I was 9 and being completely absorbed by how different it was, compared to competing Christmas programs. Whereas most early-1970s holiday shows were cartoons or family variety hours starring old crooners, A House Without a Christmas Tree was a dramatic film that mixed Christmas joy with depression in equal measure.

The movie detailed the life of a sorrowful widower, Jamie Mills, raising an 11-year-old daughter, Addie (Lisa Lucas), while also caretaking his cookie-baking mother in 1945 Nebraska. With grumpy perfection Jason Robards played the dad, a man who, ten years after his wife’s passing from pneumonia, still mourned her, while also blaming their daughter for her death. In an argument with his mother (Mildred Natwick as Grandma Mills), Jamie screams that giving birth “weakened” his wife, adding that he often wished “the baby had died” instead of his wife. Meanwhile, smart and artistic Addie simply wants a little love and a big Christmas tree.

A House Without a Christmas Tree was based on a semi-autobiographical story written by Perry’s film critic friend, Gail Rock. The project was launched when the women spent the weekend with producer Alan Shayne and his partner Norman Sunshine, who supplied the collages used in the credits and between chapters. Shayne had previously worked with producer David Susskind, but this was his first solo project.

Six years earlier, Perry had worked with her ex-husband and author Truman Capote on the television adaption of A Christmas Memory. Capote’s story was originally published in Mademoiselle in December 1956 and, the author shared a co-credit with Perry. The script won an Emmy and was later added to the Perrys’ film Trilogy (1969), which featured two other adapted Capote stories.

A decade later, in her novel Blue Pages, Eleanor gave Capote the title “The Great Writer,” and parodied him with the skill of Dorothy Parker: “The reason they knew he was a Great Writer was because he continually referred to himself that way.” In the book Perry also implies that “the Great Writer” didn’t contribute to the script and the shared credit was forced on her.

It was that prestige that Shayne used to sell A House Without a Christmas Tree to CBS. In May, 1973 Perry won her second Emmy for that special, and a month later her feature The Man Who Loved Cat Dancing, a western based on a novel by Marilyn Durham, was released. Though she had bought the book’s rights and was supposed to co-produce with Martin Poll, she was shabbily treated by her partner, the studio, and the other writer brought on the project to make it less feminist.

Perry complained publicly and it was believed that her outspokenness got her blackballed from the industry.

***

In the February 21, 1977 edition of New York magazine, there was a small item that read, “Screenwriter Eleanor Perry has just sold her first novel—sight unseen—to Lippincott, and agent “Swifty” Lazar closed the deal with editor Gene Young for considerably ‘more than $100,000.’ The book will be a love story about a woman and her adventures—from California to Cannes.”

Blue Pages, a witty roman à clef, was published two years later. It was as much about her and Frank’s life together as well as Hollywood’s ingrained misogyny, which Perry lampooned in her book. "It always starts like unbelievable heaven,” Perry told the Washington Post in 1979. “Everyone loves you, admires you, asks you if you want anything, they put you up at the Beverly Hills Hotel, give you a car, it's unbelievable. Then the script starts coming back. They cross out your lines and put in their bad grammar."

Dedicated to Alan Shayne, the book’s title, “Blue Pages,” came from a term frequently used in Perry’s profession; revisions were traditionally done on aqua-hued paper. The book begins with Perry’s alter ego, Lucia Wade, being told by formerly fat, always self-indulgent film director Vincent, “I like you very much, but I don’t love you anymore. It’s as simple as that.”

In a television interview, Eleanor claimed that her ex-husband blamed their break-up on “too much togetherness,” though she “found it exciting.” Seemingly, their separation came as a surprise to her, something she revisited in the book that chronicled the fictional Wades’ journey from struggling independent filmmakers working on small, arty projects to wealthy filmmakers down with a Hollywood system that lacked integrity, and was callous.

Blue Pages was as much about her and Frank’s life together as well as Hollywood’s ingrained misogyny, which Perry lampooned in her book. "It always starts like unbelievable heaven,” Perry told the Washington Post in 1979. “Everyone loves you, admires you, asks you if you want anything, they put you up at the Beverly Hills Hotel, give you a car, it's unbelievable. Then the script starts coming back. They cross out your lines and put in their bad grammar."

The Vincent Wade character, who’d started off as a charming boyfriend, later became a monster husband who lied about his cheating and the quality of Lucia’s scripts; at one point during an argument he knees her in the belly; calls her “mother” or “old lady” as an insult; and one night drags her to the bathroom, and forces a sedative down her throat.

In a profile of Perry in the Los Angeles Times in 1979, the journalists pointed out that while Blue Pages was a Hollywood novel, it was also, “…a book about working women and above all, middle-aged women and their plight.”

Blue Pages has been out-of-print for decades, but I discovered its existence on the Neglected Books site, where it was part of a larger feature about Hollywood novels. “I wrote Blue Pages out of desperation,” Perry told The Los Angeles Times in 1979. “I was so frustrated when nothing I wrote for film was produced…it was a simple step, under the circumstances, to employ myself, to write my own thing,”

While researching Eleanor Perry I was reminded of the many independent-minded women I saw in the news during the 1970s (Shirley Chisholm, Gloria Steinem, Angela Davis), in films, (Claudine, An Unmarried Woman, Girlfriends), on television (Mary Tyler Moore, Christie Love, Maude) and among my mom’s friends, who worked hard, started businesses, ran for office, launched theater organizations, got advanced degrees, took secret driving lessons, and dealt with the world seriously while maintaining a sense of humor.

Still, Blue Pages had its detractors. In the April 12, 1979, edition of the Washington Post, writer Megan Rosenfeld described it as “hateful,” while comparing it to “other books of sexual revenge by women writers.” However, as Perry insinuates in the novel, after the protagonist Lucia Wade is dissed by a female movie star, not every woman should be considered an ally. “The experience did toughen me up, I guess,” Lucia Wade thought in the book, “in the sense that afterward I no longer believed all women were my sisters.”

While researching Eleanor Perry I was reminded of the many independent-minded women I saw in the news during the 1970s (Shirley Chisholm, Gloria Steinem, Angela Davis), in films, (Claudine, An Unmarried Woman, Girlfriends), on television (Mary Tyler Moore, Christie Love, Maude) and among my mom’s friends, who worked hard, started businesses, ran for office, launched theater organizations, got advanced degrees, took secret driving lessons, and dealt with the world seriously while maintaining a sense of humor.

Journalist and film critic Janine Coveney, the writer of the Words on Flicks Show blog, has admired Perry’s filmography for decades. “What I found interesting was her ability to present stories about mental instability in a realistic and empathetic way. David and Lisa opened viewers' eyes to how human connection can help even the most troubled teenagers find peace, while The Swimmer takes us directly inside the sadly scrambled mind of a man who cannot mentally accept that his world was turned upside down. In Diary of A Mad Housewife, we see a character who society says should be satisfied with a traditional female role, but who chafes at the societal strictures and misogynistic treatment that are considered standard coming out of the 1960s. The filming of that controversial novel was a significant breakthrough in the portrayal of women's issues.”

Two years after Blue Pages hit bookstore shelves (the shops on 5th Avenue were her favorite), Eleanor Perry died on March 14, 1981, at her Manhattan home, which was, as journalist Megan Rosenfeld described it in her backstabbing profile, “…conveniently located between the Plaza Hotel and the St. Moritz…walking distance from Lincoln Center and Broadway.” She was 66.

In her New York Times obit, reporter Carol Lawson wrote that Eleanor “had no problem criticizing the industry for the terrible portrayal of women as victims and sex objects, attributing this to the men who write, produce and direct most of them. Mrs. Perry once said, 'It seems women are always getting killed or raped, and those are men's fantasies we're seeing, right?'”

Mrs. Perry once said, 'It seems women are always getting killed or raped, and those are men's fantasies we're seeing, right?'” So true. I’ve thought that since I was old enough to watch movies. What a wonderful article.

Oh my goodness! I had forgotten "The House Without a Christmas Tree" and "David and Lisa" and certainly had no idea the same mind was behind them! Thank you, Michael Gonzales! My mom's favorite book is "The Man Who Loved Cat Dancing," too.

It also resonates with me about seeing powerful women in the news and doing things, growing up (I'm 57). I wish today's kids had that, but I don't think they do.