Word Games

Diane Mehta on learning the frantic art of scrambling for words from her speedy and strategic 21-year-old son.

After playing anagrams for several hours via Game Pigeon on my phone with my son, who is in college, he wrote between classes and said, “Mom, stop.” He is a physicist and has ADHD, and we are part Indian, so we all know that we both have certain talents. Mine is fast computation, his is quantum things, and he’s racecar-fast. He talks faster than me but not as fast as debate team talkers, who fit an entire unintelligible argument into two minutes.

I inherited my mother’s spirited, wavy ideas and intellectual curiosity, and he has my father’s hyper-logical, Mensa-like puzzle brain. You’d think I’d know better than to play anagrams with a child whose father is in the elite leagues of Scrabble online and about to go on Jeopardy. My family loved playing Scrabble when I was a kid, but my father, strategic and analytic yet not literary, beat all of us with our fancy words and poor technique. For my son, who is 21, everything moves fast fast fast. I type 103 words per minute, and he types faster. I sprint through anagrammatic word-making with ferocity, allowing the letters eat up my hours and months, and find I am not so fast at all.

To put this high-pitched thriller game in context, music with a club beat accompanies the anagrams app, a national anthem of failure for moms, or a minute-long panic button for moms who are no longer 21 or even 51. Ten, twenty games later, I bring the sound all the way down, and my thumbs are losing their thumbprint but it’s fine because this is how I am able to interact with my college-age child who, a physician explained when was 7, had a mind so fast that his sentences couldn’t keep up with his mind, that he was skipping phrases or half-sentences to express the full measure of what he wanted to say. I’d figure out the implied diction and try to keep up.

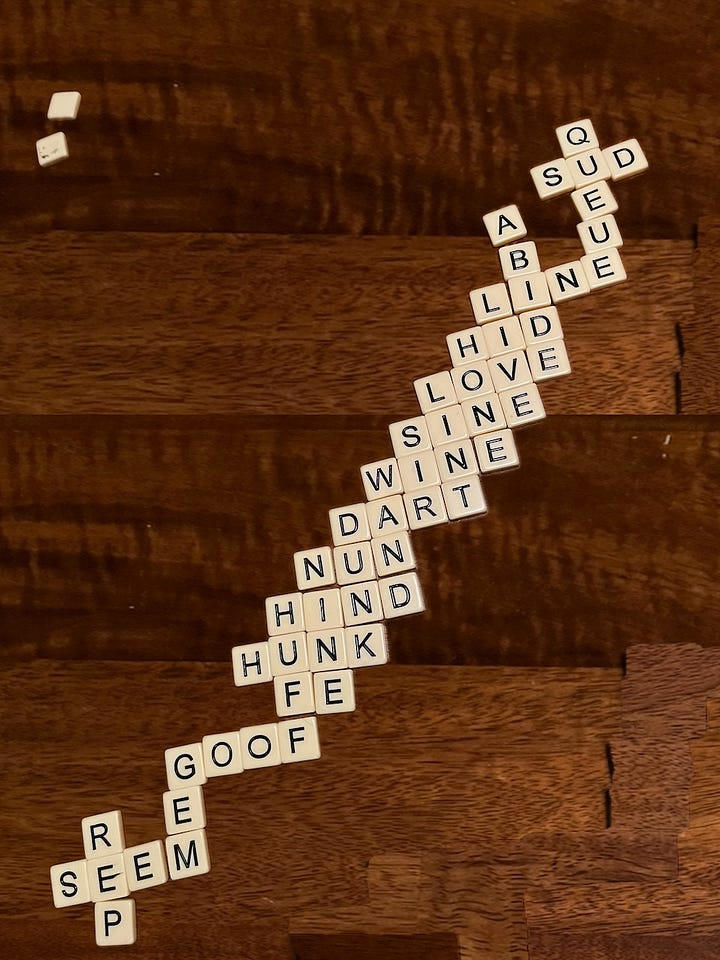

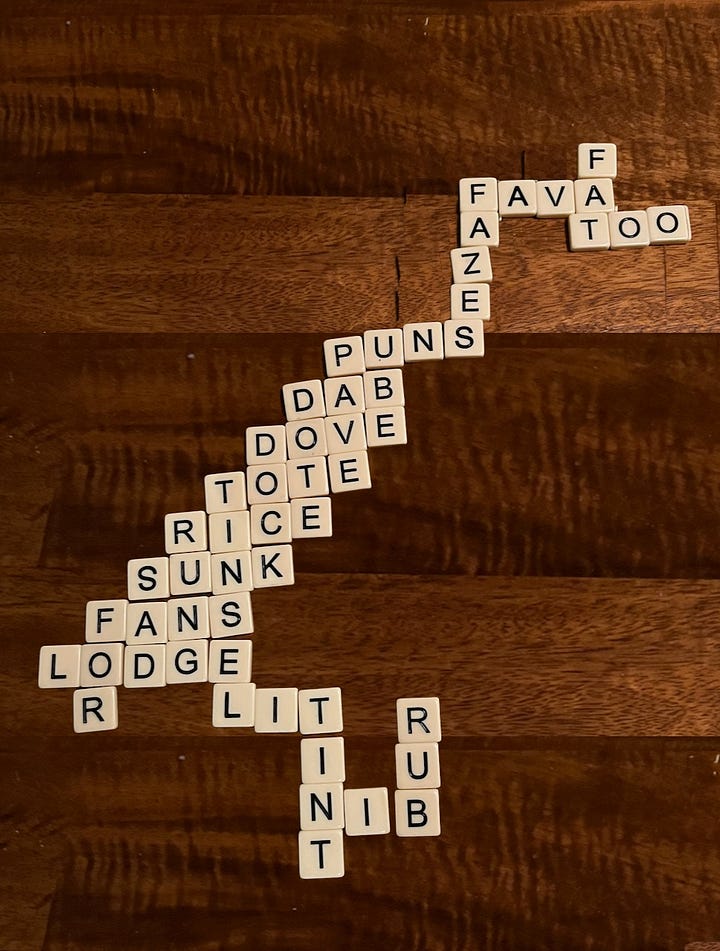

I can multi-task and zigzag across a kitchen and make twenty phone calls while on deadline and beat the deadline and then play twenty games of anagrams in-between whatever I am doing. But there is no such thing as fast compared to someone with the skill of intuiting words that do not, in English, really exist except in things like an iPhone anagrams app or Scrabble dictionaries, by which I mean they are words like “xi” or “dsomos” and the intelligence of the game does not hinge on having a good vocabulary but in punching letters at mad speeds and matching or switching vowels, scanning endings, and flipping around letters to make words that “seem like words.” I see it as a pop culture digital-native skill.

I inherited my mother’s spirited, wavy ideas and intellectual curiosity, and my son has my father’s hyper-logical, Mensa-like puzzle brain. You’d think I’d know better than to play anagrams with a child whose father is in the elite leagues of Scrabble online and about to go on Jeopardy.

After months, I got better at the “seem-like” words, and once in a while I’d hit a high score and celebrate with an emoji, and my son would send back a score triple mine with high-caliber words worth thousands of points, and I guess his fingers are bionic because I cannot understand how that many letters can be typed with two thumbs into a phone’s miniature keyboard in 60 seconds, but I try. Once in a while, I take a typing test or three online, to amplify my score with practice, and try to get to 110, or 115, where I know my son can go.

The other way to speed up is to do Indian-style computation, which is to say that when you grow up in India, like I did, you get a ton of computation homework, and memorization is the main learning mode. I’m bad at math but great at computation. When my son would come home from fifth grade with, say, five computation problems for homework, I was appalled. I learned math by rote. So I’d give him another five pages of computation, and do it with him (“1,2,3 Go!”) so he’d feel competitive and get through my assignment. Who absorbs technique and decimal relationship issues by doing just a few math problems? Nobody.

This is why I ended up getting sucked into anagrams. But when five-letter anagrams became too easy for my son, he spent a few dollars and upgraded to seven-letter anagrams, so I had to adjust my game, the spacing and angle of my thumbs, and my eye-hand coordination.

Let me be clear that my game continued to be terrible. Occasionally I’d strike gold, with a high score, and would dance around and then press my thumbs to the glass again and listen to the panic-clock beat that ticked off the final seconds of the next found. There’s nothing like getting a score of 200 for only getting two three-letter words rather than, say, 20,000 points for getting the anagram and a slew of four- and five-letter words in addition to the small words to make you feel old and brainless, but I’m not dead yet, and I suspect that my 92-year-old father would probably be an ace if he were as nimble with his thumbs as he is with his brain, so I keep going. (He is an aficionado of the New York Times puzzles, and gets to “Amazing” in the Spelling Bee in 20 minutes. Similarly, my son sees the Bee and takes less than a second to spot the pangram. This skill is spatial.) Hours pass, and suddenly 60-second anagrams that I use as an intellectual brain-building break, an alternative to social media, turn into daily drills. My improvement is slow.

It is not easy to figure out how to communicate with a child in college. For us, this is the only game in town. It was a good move on my part to fill the space between raising a child and raising a not-so-communicative adult.

It is not easy to figure out how to communicate with a child in college. For us, this is the only game in town. It was a good move on my part to fill the space between raising a child and raising a not-so-communicative adult. Growing up, it is a rite of passage to play board games, card games, word games. We started with Go Fish, but in high school he switched to Egyptian Ratscrew, which involves snap calculations of sandwiched, ascending, descending cards as they appear and then slapping the deck before the testosterone-fueled teenager that not surprisingly thrives in this kind of environment.

I gave up on Scrabble after my divorce, because it’s no fun with two people, but I did find a way to used my ex-husband’s expertise one October in Italy, by texting him photos of the board during a Scrabble game, and waiting for a return text seconds later: 3 letters, top right, 148 points. I’d politely place my letters on the board and surprise my opponents. I won. One woman was furious but I thought this was an effective way to maintain camaraderie and friendship in my divorce. Besides this one time, I don’t play Scrabble with my ex anymore, given his cunning way of hanging onto letters that he knows will eventually be useful, and getting some big-ticket payout at the end. My dad used to do that, too. I have always been pleased to find three- to five-letter words and land on a double.

I’m not dead yet, and I suspect that my 92-year-old father would probably be an ace if he were as nimble with his thumbs as he is with his brain, so I keep going. Hours pass, and suddenly 60-second anagrams that I use as an intellectual brain-building break, an alternative to social media, turn into daily drills. My improvement is slow.

Bananagrams and anagrams are not games for dry eyes, yet at 58, I think that my age has given me experience, and parenting has prepared me for a few things. In Bananagrams, I’m reluctant to rip apart the prettiest and most entrancing words and mess it all up, but I realize that this is the result of years of psychic losses that pile up, and so I hang onto what’s good enough. Here’s where my child is teaching me how to take more risks as I get older. What do I do each time he goes back to college and we can no longer play Bananagrams together? I download the anagrams app that I’ve deleted in a rage several times, and play against myself to wind up my confidence, and then text him a game. The outcome is the same, but once in a while I can headache my way into a good score. I think I have achieved something in the word game universe where I have fast fingers, a puzzle-ready STEM mind, ChatGPT open, and I am young.

Being young means calloused thumbs and no stomach for the beautiful failure that makes me want to play more rather than being a lonely king of anagrams or Scrabble or Bananagrams—though with the latter, I get to play with real people at a table, and I like the designs my son makes.

What’s different now than when I was young is the tender way that my son teaches me to find better combinations, reminding me to use plurals and use the “seems-like” educated-guess approach—asking first if I want help, which I always do. Suddenly I can throw out my secure words and life feels new.

Getting older is a lesson in sacrificing the smaller words that arrive with no effort. After all, it is decades since my divorce, and year three of empty nest syndrome, and time to seek out what does not come easily. The word games are manic and beautiful and a new way of feeling love. My child is at the beginning of his life and I am in a forward motion, but I am realizing that my son can help me break the spell of being stuck with the same words in the same combinations. This is reciprocity and care and it changes the decades to come.

I'm 77 and my two sons, one 55 and the other 43, and I have a daily battle with Wordle, the New York Times mini puzzle, and Connections. They are both exceptionally bright boys, and the 43-year-old is a Scrabble wizard! They both usually beat me in the timed mini puzzle, but I chalk that up to my fumble fingers more than my ability to answer the clues. It's a great way to keep in touch everyday. The youngest lives far away and I don't get to see him much. The eldest lives closer, but daily life and it's hassles, keep us apart more than I would like. I'm amazing at Wordle, meh at the mini for reasons stated above, and pretty good at connections. Both my boys have ADD, and they tell me I probably do too. I don't care; my main goal is to stay in touch and to keep my brain working. I love your piece. Good luck with the anagrams!

This is some gorgeous writing. I do not have children, but I was a university professor, and so I have tenderness for those delicate and lightning-fast boy-men. I am looking for your new book right now. Congratulations.