When Invisibility is the Perfect Cloak

Novelist Deanna Raybourn on why middle-aged women make excellent (fictional) assassins.

Pop culture has always been heavily populated with male assassins and spies, but in the last decade, the women have been catching up. From Charlize Theron’s Lorraine Broughton in “Atomic Blonde” to any number of characters played by Angelina Jolie, movies are finally showcasing how the female of the species can be deadlier than the male. But with the notable exception of Helen Mirren in “Red,” almost all of these literal femmes fatales are under the age of 45. They’re all stunningly attractive, as seductive as they are sinister, but how many of them could effectively do their jobs with the required secrecy, flying under the radar and making themselves unmemorable? Jodie Comer’s Villanelle in “Killing Eve” has the face of a Botticelli angel, while Scarlett Johansson and Florence Pugh are not exactly forgettable while taking their turns as Black Widow. So who fits the bill of the female assassin who can slip unnoticed back into the shadows when the deed is done?

Enter the older woman. As anyone who identifies as female can attest, once you pass 50, your visibility slips further away each year. With every laugh line etched onto your face, another little bit of you gets erased from public perception, at least in the US. And yet being invisible is a stupendous advantage. Being invisible gives you a chance to study others, to move quietly from place to place, to blend into the background like the most tasteful and forgettable wallpaper. There’s a wonderful story that for a decade or so during the Cold War, the comings and goings of all callers to an important American diplomatic building in West Germany were surveilled by an elderly woman. Her disguise? She didn’t have one. She simply sat on the balcony of her apartment building across the street, knitting peacefully in the sunshine as the photographic equipment hidden in the flowers of her planter boxes recorded each visitor.

As anyone who identifies as female can attest, once you pass 50, your visibility slips further away each year. With every laugh line etched onto your face, another little bit of you gets erased from public perception, at least in the US. And yet being invisible is a stupendous advantage.

Now, I suppose that story might have been embellished a bit, but I choose to believe it wholly, if only for the fact that it’s so plausible. An older woman sitting quietly is so much furniture for most people, unremarkable and unremarked upon. We dismiss these women as harmless—and that’s provided we notice them at all. Of course, this can work to the advantage of the older woman intent on a crime spree. Two different Scandinavian series have recently put elderly ladies front and center precisely because it’s so easy to overlook them as they totter around, committing dastardly deeds. Catharina Ingelman-Sundberg’s Little Old Lady (from The Little Old Lady Who Broke All The Rules and two sequels) tires of life in an assisted living facility and heads up a gang of retirees who turn to art theft to support a more comfortable way of existing. And Helene Tursten’s Elderly Lady (from An Elderly Lady Is Up To No Good and the sequel) goes a step further and delivers an octogenarian serial killer who chooses murder as a tidy solution to life’s little troubles. These two criminals don’t fly under everyone’s radar, but they manage to get away with quite a lot simply because who can imagine a gentle, elderly woman as a criminal mastermind?

But what about the woman who isn’t elderly yet but is certainly on what Hollywood would consider the “wrong” side of 50? I remember sitting in the movie theatre, watching Diane Lane and Marisa Tomei play the adoptive mother and aunt (respectively) to superheroes. As an 80s teen, I grew up watching each of them morph from fresh-faced newcomer to fully fledged sex symbol over the course of their careers. But in a society where youth and beauty are for many the pinnacle of feminine achievement, the minute a woman starts to age, she’s relegated to a supporting role—often quite literally. While Superman and Spider-Man are dashing around, averting disaster and saving humanity, Martha Kent and May Parker are left to keep the home fires burning and leaving me to wonder, where are their capes? They should be leaping tall buildings in a single bound and saving the day, but crow’s feet apparently don’t mix easily with costumed crusading.

To be fair, there have been a few older women kicking ass like nobody else in the superhero realms. Marvel’s “Black Panther” gave us Okoye and Ayo from the Dora Milaje while Wonder Woman’s island home of Themyscira is defended by the Amazon queens Hippolyta and Antiope for DC—all played stupendously by actors in their 40s. There’s something unexpected and empowering about watching a woman who is obviously not 25 using her strength and her experience to demolish her enemies. And nobody is going to overlook these women; they’re warriors born and bred to stand their ground and I suspect most opponents would turn tail rather than face them on a battlefield.

An older woman sitting quietly is so much furniture for most people, unremarkable and unremarked upon. We dismiss these women as harmless—and that’s provided we notice them at all. Of course, this can work to the advantage of the older woman intent on a crime spree.

Yet for all their sometimes superhuman abilities, they’re still only supporting players, either to men or to younger women. But they deserve to be front and center in their own stories, a feminine counterpart to the endless parade of grizzled, battle-scared male veterans, from Jason Bourne to Batman. Men are never too old to be action heroes, it seems, and if we’re going to accept that James Bond can be a swaggeringly seductive spy played by an actor nearing 60, then surely it’s time to give more mature women a shot. (Roger Moore was 57 during his last outing as Bond, in case you’re wondering.)

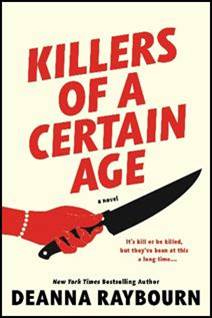

And that’s where my Killers Of A Certain Age come in. I wanted to write a book that featured older women—my four main characters are 60—on the cusp of a major life change. They are facing retirement from their work as elite assassins and wrestling with the question of who they are when they’re not killing people. They have to rely on each other, on their experience, and most of all on their ability to be invisible in plain sight to stay alive. What you don’t see, you can’t guard against, and what you can’t guard against just might get you killed—as their enemies are about to learn. This quartet of assassins is brash and badass, even if they need calcium supplements and ice packs after a hard day’s work. Killing people just isn’t as easy as it used to be when you’ve been doing the job for forty years. But they’ve learned how to adapt and the biggest lesson they’ve learned is that being underestimated is a superpower.

So, being invisible is not very appealing for the average woman, but for a killer of a certain age? It just might keep her alive.

I lived in DC the past 10 years and made it a point to observe people while riding the Metro (subway) to and from work. Two hours per day, 5-6 days/week, for 10 years. Because I'm in my 60s, I was invisible in doing so. The things I saw and learned! Invisibility was my superpower, for a very long time.

I’ve always objected to the “invisibility” complaint because it fails to be precise enough: we become “invisible” to the exact type of people whose interest should not be valued at all. But in the case of assassins I’ll buy that, if the victims are deserving.

Meanwhile I’m perfectly content to no longer be harassed as I walk down the street, or fail to engage the interest of men who’d only value me for as long as my skin stays young.