The Woman Behind the Mann

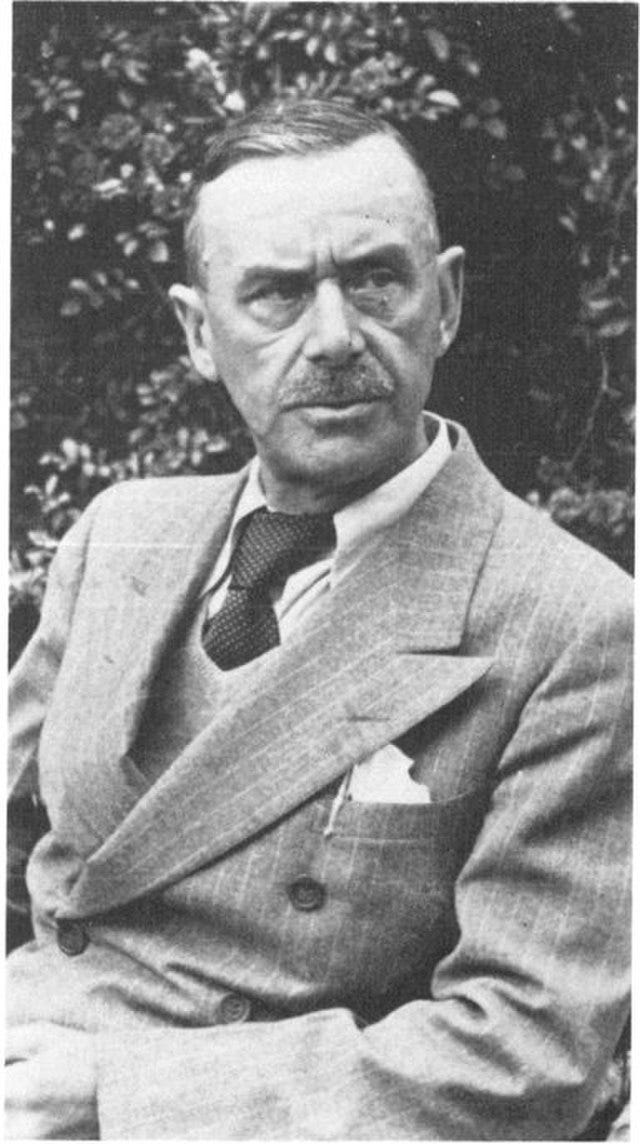

Septuagenarian Jo Salas on becoming an author later in life, and paying homage to Thomas Mann's translator—a woman first published in her own right in her 70s—in her new novel, "Mrs. Lowe-Porter."

At the age of 77 Helen Lowe-Porter told the German novelist Thomas Mann that she had decided to retire as his translator in order to work on her own writing. “The reason is perhaps silly,” she wrote to him. “In the end of my life I have so many things in my head that I find I must get them down, whether they ever find a publisher or no.” Helen had been writing fiction and poetry all her life. Decades of effort had brought much disappointment—and one major success.

Helen Lowe-Porter was my husband’s grandmother. I never met her, but I’ve always felt a connection to her story. I admire her persistence despite the demands of her career and her family—and the absence of encouragement from the two illustrious men who loomed large in her life, Mann and her husband.

As a young woman, Helen was determined to succeed as a writer. Her aunt and literary mentor Charlotte Endymion Porter sternly advised her to stay single. But when she was 30, Helen met and married the scholar Elias Lowe. Soon they had three little girls. The family lived on Elias’s slender salary as an Oxford professor and Helen’s unreliable income as a freelance translator. As Aunt Charlotte had warned, family life was in direct competition with her writing. Husbands in those days—especially a rising academic star like Elias—did not help at home.

In 1922 Helen was hired by Knopf to translate Buddenbrooks, Thomas Mann’s first novel to appear in English. It was a massive task, not only because of its 800 dense pages, but because Mann was already established in Europe as a literary giant. Introducing him to English language readers was a daunting responsibility. Helen was as anxious as she was eager.

She threw her considerable linguistic, intellectual, and artistic talents into the work, navigating frequent complaints from both Mann and Knopf about her slow pace, quelling her own self-doubts as best she could, doing her best to balance translation with child-raising. “I’m frightfully sorry about my procrastination,” she wrote to Alfred Knopf. “It is true we had lumbago and chickenpox. But chiefly I am lazy.” Her reflexive self-criticism is familiar and painful. Anyone who’s looked after sick children can sense the worry and exhaustion behind that carefully casual remark.

As a young woman, Helen was determined to succeed as a writer. Her aunt and literary mentor Charlotte Endymion Porter sternly advised her to stay single…As Aunt Charlotte had warned, family life was in direct competition with her writing. Husbands in those days did not help at home.

In 1924 Buddenbrooks was published in English. With its success, along with renewed speculation about the Nobel Prize (which came a few years later) Alfred Knopf engaged Helen as Mann’s permanent translator. Over the next three-and-a-half decades she translated 22 of Mann’s works, both fiction and nonfiction.

Helen continued to work on her own writing when she could, sneaking it in between translations, repeatedly disappointed when it failed to find publication. Then, in 1948, her play Abdication, or All Is True was triumphantly produced in Dublin with rave reviews from not only the Irish press but the New York Times and the Christian Science Monitor as well.

She’d written Abdication twelve years earlier, at the time of Edward VIII’s shocking decision to leave the throne, but it had been turned down by every producer and publisher she’d sent it to, including Knopf. After all those years of rejections of everything she’d written, Helen could hardly believe that this distinguished Irish repertory company wanted to produce her play. She attended the glamorous opening night, reveling in the sense of success at long last. “This is the happiest day of my life!” she burst out to a son-in-law who accompanied her. She was 72 years old.

As soon as Helen retired from translating, she astonished herself by embarking on a novel. By then her personal life was complicated and difficult. Her husband’s affair with their daughter’s young friend, years earlier, had fatally wounded their marriage. She did not have a permanent home, living sometimes with Elias at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, sometimes with her daughters or friends.

Wherever she found herself, she’d sit at her lap desk—just a plank across the arms of a chair—and work on her novel. The story that took form was like nothing she’d ever written: a young brother and sister who, in a mysterious instant, switch gender. She called it Sea Change and sent it with trepidation to Thomas and Katia Mann. Mann wrote a long, admiring letter in response: “You can well imagine that the subject matter of the work, especially the psychological treatment of the body-versus-soul relationship, struck a familiar chord.” But his praise was undercut by his warning that publishers might find it strange, even offensive. Helen defended it weakly: “With the fact that this little story is about the tragedy of parents and children, it might produce a slow and modest sale instead of a total loss.”

Reading Helen’s letters, her erudite, humble introductions to Mann’s novels, her illuminating essays about translation, her poetry, I heard the echoes of other women artists, then and now, torn between their creative vision and their devotion to family and profession.

As Mann predicted, her agent failed to find a publisher. The manuscript no longer exists and no one in the family recalls ever reading it. Helen, crushed by its failure, may have destroyed her work.

I can picture so clearly Helen’s astonishment at her own fertility in late age, the thrill of producing a major new work, Mann’s gratifying enthusiasm—and then the devastating disappointment when her novel remained unpublished. This final, humiliating blow might have been too much for her. Helen’s last years were tainted by bitterness and encroaching dementia. She died at 86 in a private nursing home in Princeton.

My mother-in-law, Patricia Lowe, began to write a memoir about her parents in her own old age. When she died, her work unfinished, I inherited all her research. Reading Helen’s letters, her erudite, humble introductions to Mann’s novels, her illuminating essays about translation, her poetry, I heard the echoes of other women artists, then and now, torn between their creative vision and their devotion to family and profession. I knew that Patricia would have liked me to finish the memoir that she’d started.

Instead, I began writing a novel about Helen, seeking to tell her story through the lens of my empathy and imagination. I considered giving her a final triumph, a counterfactual happier ending. I didn’t, although the novel ends with one last, imaginary work of art.

I worked on the book for a long time, researching Helen’s life, her relationships, and the times that she lived through, including the suffrage movement and two world wars. I shaped a narrative around the milestones of her life, expanded with imagined episodes and characters.

Like Helen, I’ve been drawn to writing all my life. But most of my published writing is nonfiction. My fiction-publishing history is thin. I was afraid all along that my novel, called Mrs. Lowe-Porter, would meet the same fate as Helen’s Sea Change. And now I’m in my 70s, too. Would I, like her, face a thumbs-down verdict on the literary aspirations of an aging writer?

I knew that Patricia would have liked me to finish the memoir that she’d started. Instead, I began writing a novel about Helen, seeking to tell her story through the lens of my empathy and imagination.

In this respect I was luckier than Helen. After much effort, discouragement, and essential help from others, I found a dynamic small publisher who loved my novel.

The real Mrs. Lowe-Porter might be amused. She might be gratified. More likely she’d be affronted at my boldness in writing this fictional version of her life. When I break a sweat at the idea that I might have done an injustice to the memory of a woman I greatly admire, I remind myself that it is more than Helen’s story. It’s the story of many women, past and present, who persist all their lives, even in old age, to fulfill the gifts they know are within them.

As an old-and-proud writer of 74, I love Jo’s rescue of Heken and her story from oblivion. M.F.K. Fisher was right: “The purpose of life is to grow old enough to ha e something to say.”

I had a moment of pure heartbreak when I read that 'Sea Change' is lost to us. I had already mentally queued it up in the highest tier of my TBR list.