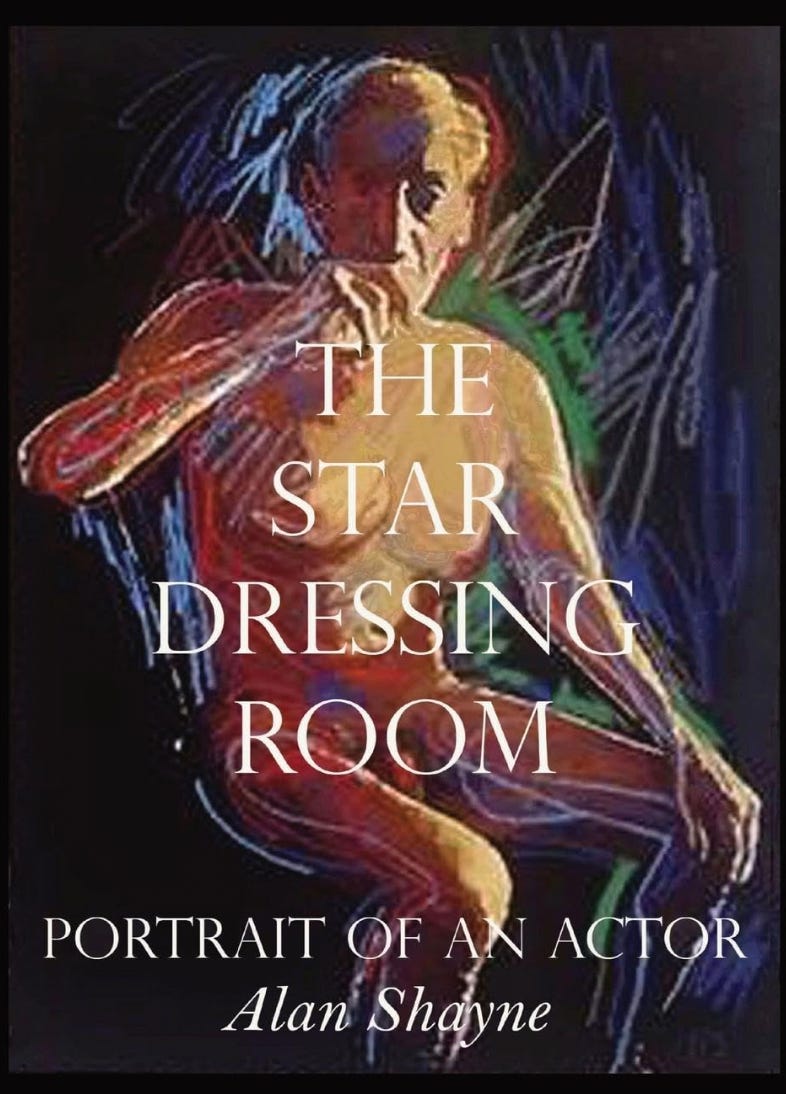

The Star Dressing Room

An excerpt of 97-year-old actor and casting director Alan Shayne's memoir.

Alan Shayne is an actor and casting director, known for All the President's Men (1976), The Bourne Identity (1988) and Hallmark Hall of Fame (1951). He has been married to Norman Sunshine since 2004.

In his memoir THE STAR DRESSING ROOM: Portrait of An Actor, Alan Shayne takes us back to 1957, when he was a struggling actor and wearing multiple hats on the Broadway musical Jamaica starring the legendary Lena Horne and Ricardo Montalban. In this excerpt, Alan tells how he became Horne’s friend and confidante. Horne helps him become Montalban’s understudy, which works just fine until Alan (who has never sung a note or danced on Broadway) has to go on at the last-minute for him—and in one of Montalban’s jockstraps! Taking temporary residency of the star dressing room for the only time in his life, Alan meets Norman Sunshine, who has been his life partner for 65 years.

Bobby Lewis, my director friend, got me back on track. He was doing a musical with Lena Horne and there was a job for me. I would again be the assistant stage manager, understudy the part of an old British Governor, and do a small part as a radio announcer, voice only. It was the best thing that could have happened to me. I was caught up in the excitement of a huge David Merrick production called Jamaica.

Bobby Lewis had been in the Group Theater and was a master at The Method. He constantly gave directions to Lena out of the Stanislavski handbook.

Lena and I had become friendly, and she begged me for help. She didn’t understand Bobby’s directions about actions and motivations. She began to doubt that she could act at all. I convinced her to be herself as much as she could.

I was at the stage manager’s desk for the entire show watching out for any problem that might arise.

The fun of the evening was visiting with Lena before the show. She often asked me to come into her dressing room and chat as her maid put her hair in rollers and then brushed it out. Lena had a light, slightly yellow complexion, with a lot of freckles, that she covered up with a dark makeup. She put the base on meticulously. As she did, she would talk about her day and ask me about mine and sometimes she’d gossip about people we knew in common.

Lena had people at her apartment almost every week after the Saturday night performance. She didn’t have to work the next day so she could stay up late and drink. She didn’t drink that heavily, but she loved sweet-tasting combinations of liquors that her husband, Lennie Hayton concocted for her.

“Alan,” a voice I didn’t recognize said. “This is Jack in the Merrick office. We’ve just had a call from Ricardo Montalban’s doctor. Ricardo is sick and you’re going to have to go on at the matinee.”

Toward the end of the first winter with the show, I heard of another possibility. Ricardo Montalban had an understudy who was one of the singers. As the show became even more of a hit, Lena worried that the understudy didn’t look old enough to play opposite her if anything happened to Ricardo. The management was looking for a replacement. I immediately asked if I could audition for it. They said no, I couldn’t possibly be right to play a native fisherman.

True, I wasn’t dark, but neither was Ricardo, and I had a scoop nose, but so did one of the dancers. I mentioned it to Lena who thought it was a great idea and insisted that I be given an audition. Of course, I knew every note and word that came out of Ricardo’s mouth, since I was in the wings at every performance. I also had watched all of his movements. My audition was a finished performance that surprised the powers that be, and I got the job. Another $15 a week and I would also be at an afternoon rehearsal every Tuesday with the other understudies.

I was my psychiatrist’s office when the phone rang, making me jump almost imperceptibly. I was brought back to the office from far away. I was annoyed when the phone rang during a session, but the doctor had explained he had to answer it in case it was an emergency with one of his other patients.

“I’m sorry, Alan,” he said as he picked up the phone. “Hello?” There was a pause while I waited, eager to continue. “It’s for you, Alan,” he said. I reached over and took the phone from him. I had given the doctor’s number to no one except the theater in case of an emergency.

“Hello?”

“Alan,” a voice I didn’t recognize said. “This is Jack in the Merrick office. We’ve just had a call from Ricardo Montalban’s doctor. Ricardo is sick and you’re going to have to go on at the matinee.”

I rubbed my tongue under my front teeth. “Will there be time to rehearse with Lena?” I asked.

“We can’t reach her, but she’s always at the theater by 1:30 so you can go over some things with her then. I know you’ll be fine.”

I hung up and started to shake. “What is it, Alan?” the doctor asked.

“I have to go on for the star today, opposite Lena Horne. I won’t even have a rehearsal!”

“But that’s wonderful. You’ve rehearsed the role, haven’t you?”

“Yes,” I replied, I couldn’t stop shaking, “but never with Lena – just in understudy rehearsals.”

“Do you know the lines?”

“I think so, but all those songs, I’ve never sung with the orchestra.” I started to fold my hands and rub my fingers against each other.

At the theater, since none of the singers and dancers had arrived, everything was dark and quiet. There was almost an atmosphere of gloom. Charlie, the production stage manager, was waiting for me. He told me Lena was not there yet, so he took me up to Ricardo’s dressing room. I stopped for a moment in front of the door. It was white with slats that made it look like a shuttered door in the West Indies. Ricardo’s name was painted in black letters above the doorknob. At the top of the door was a huge gold star marking it as the star dressing room. It’s about to be mine, I thought. I took a deep breath and felt a shiver of panic. I stopped it. I mustn’t think about it now. I opened the door to find Ricardo’s dresser standing there, smiling, waiting to help me.

Since the show was about dark-skinned Jamaicans, I had to use body makeup that the dresser had begun to apply as soon as I stripped to my jockey shorts. I hadn’t thought, in my rush, what I would wear under Ricardo’s skimpy fisherman clothes, since my jockey shorts would show through. Luckily, the dresser had a newly laundered jockstrap with Montalban printed across the band. As I put it on, I thought not only am I in the star’s dressing room, I’m even wearing his jockstrap.

Although I was in very good shape, I wasn’t the movie star hunk that Ricardo was. My hair had been dyed black in case I ever had to go on, and I used Ricardo’s dark pancake makeup and some eyeliner. There wasn’t much I could do to look like the rest of the cast, but then Ricardo didn’t look much like them either.

I hung around the stage waiting for Lena. I could hear the noise of the audience coming in. But I now realized that the other understudy was family, and I just wasn’t. But Lena had chosen me so there was nothing I could do.

I walked around the stage marking out places where I would have to play scenes. Even the people I was most friendly with avoided me.

I was suddenly a stranger in a strange land.

He took me up to Ricardo’s dressing room. I stopped for a moment in front of the door...Ricardo’s name was painted in black letters above the doorknob. At the top of the door was a huge gold star marking it as the star dressing room. It’s about to be mine, I thought.

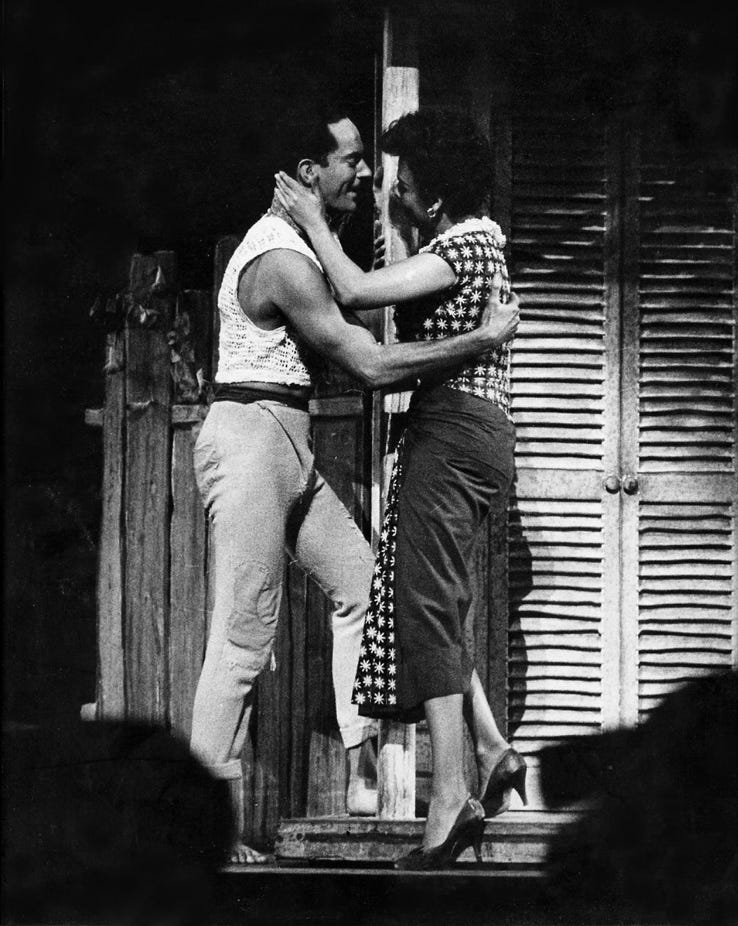

Lena appeared looking incredibly beautiful as always. The stage was still dark except for the work lights. She walked over to me, dressed in her opening costume. “Hello, Koli,” she said, and I could feel a strong emotion welling up in me. She had used the name of the character I was about to play. It was the nicest thing she could have done to reassure me. “There’s no time to run scenes,” she said, “but you know everything so well – you’ll be fine.”

“Lena,” I said, “there’s just one thing. You have to let me kiss you.”

I knew I was about to do love scenes with Lena Horne, and although we were friends, we were about to break a barrier that had to be broken, or I couldn’t play the role. She nodded her head, and I kissed her on the lips with the same passion that I would feel when we did the love scenes. She then went up the stairs to the little house on the set from which she made her first entrance. I watched her go and suddenly saw that she was more nervous than I was.

I waited for the overture to begin and then I heard an announcement over the loudspeaker. The stage manager’s voice was loud and clear.

“At this afternoon’s performance, the part of Koli, usually played by Ricardo Montalban, will be played by Alan Shayne.”

There was a great groan from the audience that must have been heard in Newark. I felt as if I had been physically slapped. The orchestra quickly began the overture to keep people from leaving the theater. I took a deep breath. OK, I thought, they don’t want me, but f**k them, they’re going to get me, and, somehow, they’re going to like me. I’m going to be a big star, and this is going to be a snap. I pushed out my chest, pulled back my shoulders and decided to have the time of my life.

The overture ended, the curtain went up, the music started again, and I heard my cue. I sang the first few lines of the opening song from offstage. Then the boat was pushed by the stagehands, and I went sailing down to the footlights. I stepped out of the boat and sang “Savannah,” begging Lena, as Savannah, to come out of her little house to be with me. I wish I could say that I went out there and came back a star, like in the movies. I didn’t. But the show went very well. I never forgot a line or a lyric. I invented a few dance steps that Jack Cole, the choreographer, would have winced at.

The audience didn’t know the difference. They seemed perfectly happy with me after the shock of not getting the movie star they’d paid for. People said later that I’d performed as if the part had always been mine, that I looked great and had loads of charm, but I didn’t kid myself. I could pretend for a couple of hours that I was a star, but it was over once the curtain came down. I did get a terrific hand from the audience at my solo curtain call, but the cast only applauded me perfunctorily when we were behind the curtain.

Lena was sweet and complimentary, but I realized she was brooding about the groans that greeted Ricardo’s absence. She took it personally that she wasn’t enough for the audience by herself, when, of course, she was the one everyone came to see.

Unfortunately, since I had to perform that night as well as the rest of the week, I ended up wrecking my voice. I had to be sent to a doctor, called by people in the know as “Doctor Feelgood.” He gave me an injection that made me feel wonderful, and I did the show singing like a bird.

Only years later did it occur to me that I had been given drugs. I did discover, however, that in order to do the show each time, as the audience groaned when my name was announced, that I still had to psych myself into believing I was a star, or I couldn’t get through the show. It made me behave, for a short time, like an important, rather imperious person. It had never been a part of my DNA. Fortunately, for me and my friends, it only lasted until a short time after the show, and then I was myself again.

The July heat was eliminated by the huge theater air conditioners, but the physical activity of singing and dancing drained me, even though by now, I had played Ricardo’s role many times. The performance had gone off without a hitch. I had never made a mistake in a lyric or a piece of business since the first time I had done the role several months before, when I had surprised everyone.

“At this afternoon’s performance, the part of Koli, usually played by Ricardo Montalban, will be played by Alan Shayne.” There was a great groan from the audience that must have been heard in Newark. I felt as if I had been physically slapped.

I saw that it was time for my bow, so I lifted up my head and ran on the stage, smiling at the enthusiastic audience. They applauded warmly and then thunderously when Lena Horne appeared. She looked at me affectionately, and when the curtain went down, she said, “It was very good today.” Several of the actors came over and slapped me on the back. The cast had finally decided to accept me substituting for Ricardo, after resenting my not being at all right to be one of the Jamaicans on the island. Ricardo was no more right than I was, but he was a star. I think they had finally realized I was keeping the curtain up. If I weren’t there, there wouldn’t be a show. Ricardo’s dresser came onto the stage and put a terrycloth robe around me, and we walked together to the dressing room.

I was standing on a box, naked, except for some jockey shorts I had pulled on over the jockstrap I had to wear in the show. My dresser was repairing my body makeup so I would be ready for the evening performance. My mother came in, reached up to kiss me on the cheek, said how wonderful I’d been and sat down in the armchair. There was a knock on the door and the dresser opened it and let in an actor I’d worked with on a television show. Another man accompanied him.

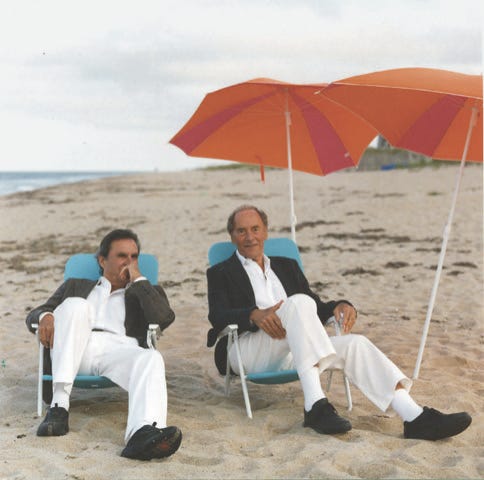

I have replayed this scene so many times in my mind. It is only when a moment changes your whole life that you keep going back to it. Did I know at the time how important it was? Of course not. I do remember I was stunned by the man who was with my actor friend. He was about my age and phenomenally handsome. He was the same height as I was (though standing on my box I towered over everyone) with a mass of thick, black hair that fell across his forehead, almost hitting his startling brown eyes. His eyes looked both aggressive and hurt at the same time. He had a big, curved nose that, together with his other features, made him an arresting presence like a young, intense movie star, or a French, avant-garde writer. His skin was deeply tanned from, I guessed, lying on the beach in the July sun, but there was no sign of vanity about him. He was wearing a seersucker jacket, a pair of gray pants, a tie, and a white shirt (people dressed for the theater in those days) but nothing to call attention to himself.

I was able to study every aspect of him since I was looking into a mirrored wall and could see him in back of me. All of this was taking place as my actor friend praised my performance profusely. I barely heard him. I just kept looking at his companion. “This is a friend of mine from California, Norman Sunshine,” the actor said.

I tried not to show too much interest. “How do you do,” I said formally, but I panicked that the man was not from New York, and I’d never see him again.

“I thought you were very good,” he said, but his face was unsmiling, as if there were more serious things in the world to talk about.

“Thank you,” I said as I turned back to my dresser who was applying more dark makeup to my body.

My mother had settled into her chair after I introduced her and had begun to babble about shopping for some gloves and having trouble finding them.

I have replayed this scene so many times in my mind. It is only when a moment changes your whole life that you keep going back to it. Did I know at the time how important it was? Of course not. I do remember I was stunned by the man who was with my actor friend. He was about my age and phenomenally handsome.

I thought I’ve got to make them stay, at least long enough to give Norman the right impression. He seemed so totally uninterested in me. But here I was, practically in the nude with my dresser patting every part of my body with makeup. And I’m making everything worse by still having the star personality that gets me through the show. It must seem fake to someone like Norman. This guy must think I’m a horse’s ass carrying on like this. I wanted to say to him, “Look, this isn’t me. I’m a really decent person.” He seemed so serious and sensitive and shy. I wanted to get through to him, but I couldn’t in front of his lover, and my mother being there didn’t help.

“You don’t have to rush,” I said. “I don’t go out between shows. I just take a nap. Maybe you’d like a drink.”

“We have to get to dinner,” Norman said. I was afraid I’d sounded too eager, so I resumed my star facade.

“Thank you so much for coming back,” I said graciously. I turned to Norman, “Very nice to meet you.” I watched the two of them walk through the door.

A week later, as I was rushing up the stairs from the subway on my way to work, there was Norman at the top of the landing. It was like a movie. The sun was setting behind him and he was backlit by its rays. For a moment I thought it was someone who looked like him, but there was the same dark hair tumbling down toward his eyebrows, the same intense look of being a million miles away, as if he were thinking of something important that couldn’t be shared with the world. He was carrying a huge art portfolio.

“Hello,” I said. He looked at me, squinting his eyes slightly as if he was trying to remember who I was. “We met in my dressing room,” I said.

“Oh yes,” he replied, “I didn’t recognize you.”

I wanted to say, “you mean with my clothes on?” but he seemed so humorless that I didn’t. People were going up and down the stairs and we seemed to be in the way.

“Well, I’d better be going,” he said. “I did enjoy your show. See you around.”

And he was gone.

`

This was so good I now have to get his book. I wished the story continued and I was sorry that it ended. This was so lovely.

I read the excerpt that was published in The New Yorker as well and it was great. Very funny.