Hip-Hop, which in this insistence means the music we know as rap, celebrated its 50th anniversary on August 11th, the date in 1973 when Bronx teenager DJ Kool Herc pioneered the genre and scene while spinning at a party for his little sister Cindy. Herc’s homeboy Coke La Rock talked over a microphone the DJ had left on a table, and both are credited with throwing the first rap jam. Though I’m a native New Yorker who grew up in Harlem, it would be a few years before that musical style would trickle down from “the boogie down” Bronx to me.

However, in the summer of 1977, a few weeks after my 14th birthday, I was turned out after hearing Sugar Hill record-spinner DJ Hollywood and rapper Lovebug Starski at the annual 151th Street block party. Although that was also the year of the intense heat waves, Son of Sam, a blackout, and the Yankees winning the World Series, it was those hours observing DJ Hollywood that stand out the most for me from that summer. They changed my life.

In the summer of 1977, a few weeks after my 14th birthday, I was turned out after hearing Sugar Hill record-spinner DJ Hollywood and rapper Lovebug Starski at the annual 151th Street block party. Although that was also the year of the intense heat waves, Son of Sam, a blackout, and the Yankees winning the World Series, it was those hours observing DJ Hollywood that stand out the most for me from that summer.

In 1987, a decade after that first ear-opening experience, I wrote my first record review, foaming at the pen over the Beastie Boys’ wild-styled debut record Licensed to Ill. That piece was my gateway to hip-hop writing. Three years later my friend, writer Havelock Nelson, asked me to co-write a hip-hop guide book with him. Published in 1991, Bring the Noise: A Guide to Rap Music and Hip-Hop Culture (Harmony) was an anthology of New Journalism-style essays that combined journalism, autobiography and sociology. Inspired primarily by a few Village Voice writers (Greg Tate, Barry Michael Cooper, Harry Allen and Nelson George) who came before us, we were contributing to the then new writing genre that would become known as “hip-hop journalism.”

Three months before the book’s November, 1991 publication date, I was hanging out at a New Music Seminar turntable battle at Irving Plaza when I ran into two editors from The Source—a magazine covering the entirety of hip-hop culture—including politics, founded by Harvard students Dave Mays and Jon Shecter in 1988. They were hawking their publication from a table in the night club’s balcony.

“I would like to write for you guys,” I blurted to editors Shecter and James Bernard. Two days later I sent each an advance copy of Bring the Noise, and James contacted me a week later with an assignment to write about Trenton, New Jersey rappers Poor Righteous Teachers (Wise Intelligent, Culture Freedom, Mike Peart and Father Shaheed), whose single, “Rock This Funky Joint,” was a hit.

In 1987, a decade after that first ear-opening experience, I wrote my first record review, foaming at the pen over the Beastie Boys’ wild-styled debut record Licensed to Ill. That piece was my gateway to hip-hop writing. Three years later my friend, writer Havelock Nelson, asked me to co-write a hip-hop guide book with him.

While I had interviewed rappers before, none of my previous stories had taken me off the island of Manhattan or outside of conference rooms, recording studios or publicity offices. For my debut Source story, I spent the day with those guys at Donnelly Homes, the low-income housing development where they lived, as well as other locations. My story “The Road to Righteousness” was published in the November, 1991 issue. That marked the beginning of my decade-long working relationship and lifelong association with the magazine once dubbed “the Rolling Stone of hip-hop,” which included eight cover stories, numerous articles, and a regular column called “Back to the Lab.”

My decade at The Source was an adventure—from interviewing Cypress Hill, the blunt-wielding subjects of my first cover story, at a Philadelphia tattoo parlor, to meeting actor Robert De Niro while shadowing Lauryn Hill (who was meeting with director Joel Schumacher at the Tribeca Film Center about a starring role in Dreamgirls), to chasing down producer Pete Rock, who kept ducking me out until me the A&R dude from Loud Records tracked him down at producer Marley Marl’s house in Spring Valley.

The editors, though young and new to publishing, were serious folks. Writers were encouraged to dive deep, spend hours (sometimes days) with our subjects, and compose longer (hopefully more complex and nuanced) stories than what was published in Word Up and Right On. For those of us with a little gonzo in our style (Ronin Ro, Bonz Malone and Ghetto Communicator), it was a luxury to have 3,000 words to spend on one subject. Having wanted to be a writer since I was a boy, my goal was to create the kind of longform journalism published in the New Yorker and Esquire, except make it Blackadelic as hell.

I wrote in the middle of the night, because I worked a day job in the recreation department of the Catherine Street Homeless Shelter on the Lower East Side. Along with three other aides, we provided a safe space for the kids living there in which to do homework, receive tutoring, play games and, every day at 3:30, watch the hip-hop program Video Music Box. Most of the rappers I covered were heroes to the kids, but, like Batman, at the shelter, I never revealed my other life.

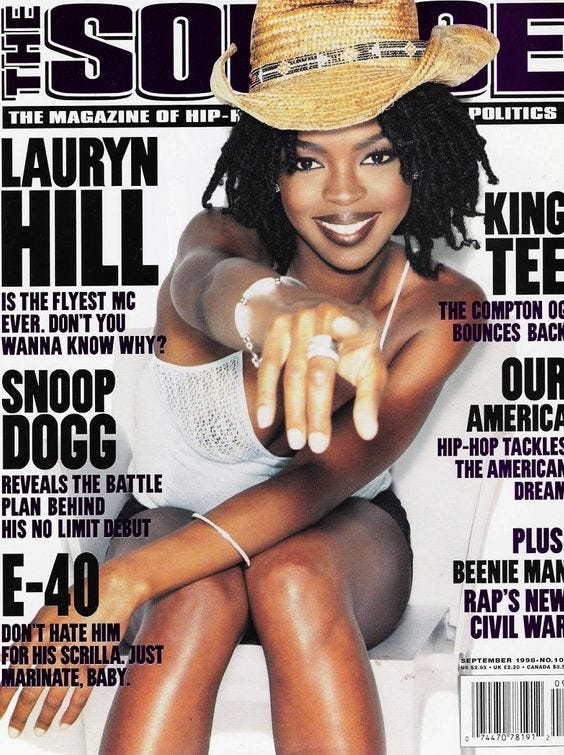

Though much as been written and discussed about the cover stories I wrote on Lil Kim/Foxy Brown (1997), my favorite female rapper feature was an MC Lyte piece published in 1993. Lyte emerged on the scene in 1987 with the anti-crack anthem “I Cram to Understand U (Sam)” followed a year later with her full-length debut Lyte As a Rock (1988). Whenever music journalists discuss that fruitful year that gave us so many rap classics, Lyte should always be a part of the discussion.

Three months before the book’s November, 1991 publication date, I was hanging out at a New Music Seminar turntable battle at Irving Plaza when I ran into two editors from The Source—a magazine covering the entirety of hip-hop culture—including politics, founded by Harvard students Dave Mays and Jon Shecter in 1988. “I would like to write for you guys,” I blurted…

I relished the opportunity to interview Lyte when she was promoting her fourth album, Ain’t No Other. Though the lead single was the hard-hitting “Ruffneck,” I preferred “Brooklyn,” her celebration of the borough years before gentrification. “There is a spirit of youthfulness in ‘Brooklyn,’” she told me, “because it reminds me of when I was growing-up there. I just wanted to write about the people who live there, the people who come out of there and the people who are too scared to go there. Brooklyn is everywhere.”

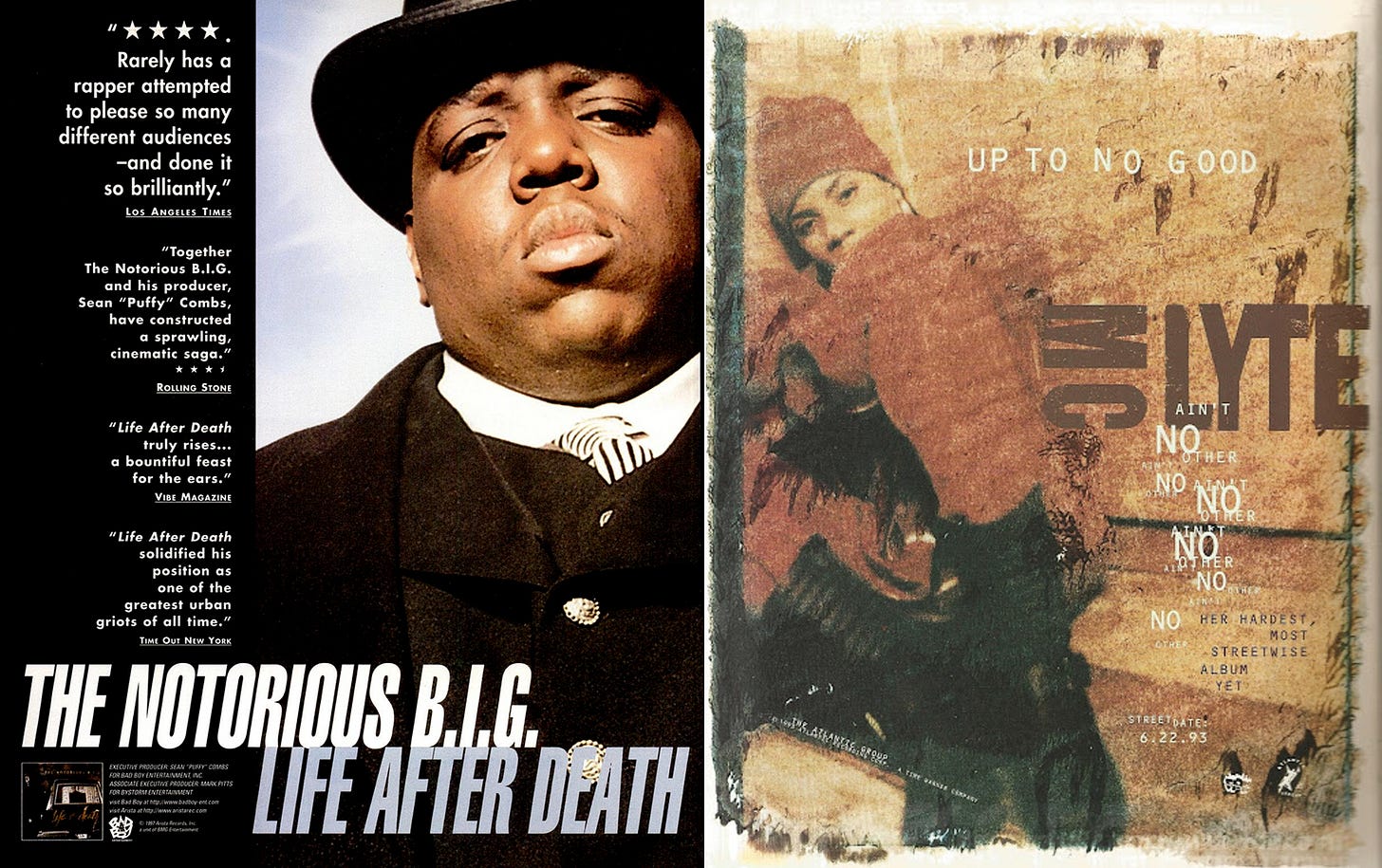

Like Lyte, there were many in hip-hop who “represented for Brooklyn,” but in the ‘90s the most popular were the Notorious B.I.G. and Jay-Z. Biggie Smalls (as he was first called) was discovered through a Source column called “Unsigned Hype.” Designed to bring unknown rappers to the attention of record companies, other “unsigned” winners included Mobb Deep, Common, DMX and Eminem. Still, as both a rapper and lyricist, I preferred Big’s two studio albums (Ready to Die/1994 and Life After Death/1997) over the others.

Though I never interviewed Big for the magazine, in March, 1997 I was assigned a review of the second album. Spookily, when I was in the middle of listening to it, Havelock called to tell me Biggie had been killed in Los Angeles. Most believed the murder was tied to the infamous East Coast/West Coast war between Big (and Bad Boy Records) and former friend Tupac Shakur (and Death Row Records), who himself had been killed six months before. While processing my sadness about Big’s death, I wrote my review, finishing it days later.

The Source had a rating system that was represented by microphones and Life After Death was awarded five mics by the “Mind Squad” editors. There are people who still believe that rating was guided by sentimentality, but I’m not one of them.

Eight months after Big’s death, Jay-Z released his second album In My Lifetime, Vol. 1. He’d been in the middle of recording it when his friend and fellow Brooklyn ambassador was slain. “You know, in this business it’s really hard to click with other rappers,” Jay told me in 1997, “because it’s so hard to trust people. But, Big was different. He was one of few people I wanted to hang around and develop a relationship with, because he was a funny dude.”

After Jay’s record company Roc-A-Fella partnered with Def Jam, business partner/manager Dame Dash decided to have a listening session for In My Lifetime, Vol. 1 at an all-inclusive resort in the Bahamas, and I got to go. On our second evening on the island, the publicist arranged for Jay and me to sneak off to another hotel where we played blackjack together. I’m a bad card player, but Jay, who later confessed he used to hang-out in gambling spots in Brooklyn, played like a professional. “You know playing cards is a lot like life,” Jay said after I lost $100 in minutes. “Sometimes you might have to double your bets, while other times it's best just to walk away.”

***

As beneficial as The Source was to many artists’ careers, there was always a rapper, producer or record executive who had beef with it. Either they felt they didn’t receive the number of mics they deserved, or were mad that a journalist wrote something they didn’t like. The only time I felt unsafe was when The Source considered pulling Jay’s cover in favor of Dr. Dre’s supergroup The Firm.

Pissed off, Dame Dash sent word insisting the magazine kill the story. I refused. The following day I was at the magazine, editing. When I went to lunch I saw Dame parked in front of the building. He blew his horn and waved me over. “Get in the car; I want to talk to you.”

Nervously, I chuckled. “I’m not getting in your car.”

He smiled. “Just get in the car.”

“I’ve seen that movie, it never ends well,” I replied and walked away. When I returned a half-hour later, publisher Dave Mays and editor-in-chief Selwyn Hinds were in Dame’s back seat. In the end it was decided that Jay and The Firm would split the covers.

***

At The Source I also wrote book reviews, articles on filmmakers, and a 1994 profile on bass player Bootsy Collins, known for his work with James Brown and George Clinton’s bands, as well as top drawer solo albums (Stretchin' Out in Bootsy's Rubber Band, Bootsy? Player of the Year) from the ‘70s. "The rappers of today remind me of the way we were back then, creating new forms of Blackness,” Bootsy said. “Whatever people told us not to do, we did more of. Rap music kept the funk alive…The same way I play bass, Dre plays his sampler."

When I went to lunch I saw Dame parked in front of the building. He blew his horn and waved me over. “Get in the car; I want to talk to you.” Nervously, I chuckled. “I’m not getting in your car.” He smiled. “Just get in the car.” “I’ve seen that movie, it never ends well,” I replied and walked away.

In 1998 the lines between soul music and rap blurred with the Lauryn Hill’s solo masterwork The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill. We already knew how dope she was as a member of the Fugees, and Miseducation proved her passion and ambition. "Being successful has always been more pressing to them (fellow group members Wyclef and Pras), while I was more about making music for love and joy,” she told me “When Marvin (Gaye) created What's Going On, even Berry Gordy thought he was crazy. It's that kind of risk-taking that is sorely lacking in music, be it rap or rhythm & blues.”

***

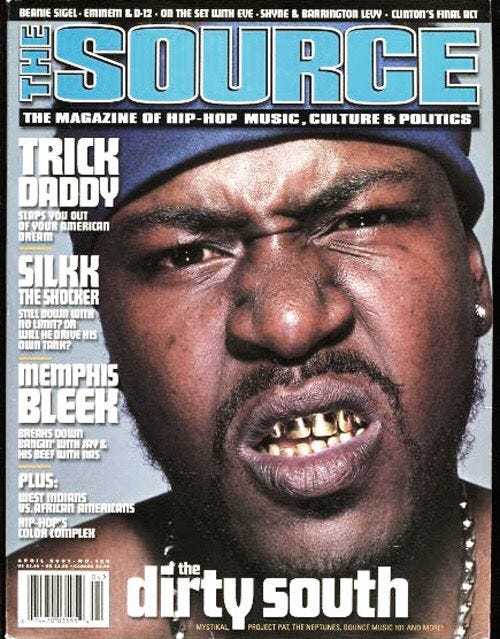

My Source swan song was a Trick Daddy cover story, which involved me chasing the rapper around Miami for a few days while he went to strip clubs, gulped Hennessy, and smoked cocaine-laced blunts. “Trick is a wild boy and I needed a wild boy like you to do the story,” my editor told me. When I finally got to talk to Trick, I realized how much pain he was in from being raised in poverty, battles with neighborhood outlaws, and days in prison, hence the distractions and self-medication.

“Where I grew up, half my graduating class is now dead, a couple are in wheelchairs attached to shit bags, others are doing life sentences,” he said. “That shit was no fairy tale.” Two weeks later, I delivered an intense story, but it damn near killed me. During that time the magazine was also going through their third editorial shake-up in a decade, and it seemed the perfect time to step away.

Most of the #Hip-Hop50 celebrations and tributes have been geared toward folks who rocked the mic or produced the tracks. However, let’s take a moment to salute the writers and editors at The Source who contributed important work throughout the 1990s and early aughts. For many The Source was their bible and we writers were simply spreading the hip-hop gospel.

I love Michael A. Gonzales's memoirs. They will make a terrific book. Not only are they extremely well-written, they also document important moments in American history and culture.

Michael, this is SO compellingly written, as one might expect from a prolific writer like you. You had me on the edge of my seat. I love the way you contextualize 1977 right off the bat, in exquisite detail: "I was turned out after hearing Sugar Hill record-spinner DJ Hollywood and rapper Lovebug Starski at the annual 151th Street block party. Although that was also the year of the intense heat waves, Son of Sam, a blackout, and the Yankees winning the World Series, it was those hours observing DJ Hollywood that stand out the most for me from that summer." I see you as a fourteen-year-old but I was right there with you in 1977 (just a tad older). So funny how the news swirls around us, whatever murky, predator-infested sea we happen to be swimming in during any given year. And yet, as kids, we have our eyes on other prizes. Wish I could go back there. Thanks for a great story. https://www.margaretsmandell.com