The Problem with Nostalgia

Michael Musto argues that wearing rose-colored glasses always leads to an unfair distortion — looking back on the best of the past while comparing it to the worst of the present.

Nostalgia Isn’t What It Used To Be was the hilarious title of Oscar winning actress Simone Signoret’s memoir in 1978, and it’s truer than ever. Seeing the past through rose colored glasses is an increasingly myopic process, especially as technology makes giant strides forward and former modes of communication resound with an astounding obsolescence.

As I handily crank out articles like this on my computer and shoot them to my editor via email, do you really think I miss the days when I had to type out a piece on a ratty Smith Corona, make changes with Wite-Out, scissors and Scotch tape, and then hand deliver the thing — sometimes in a blizzard or rain storm — to the publication, only to have to redo the whole process when a rewrite was required (after pre-Google fact-checking took up to an entire day)? Do you somehow assume that I long for a return to the time when I was terrified to leave the house because I could miss a business call? (In the ‘70s, answering machines were not prevalent and cell phones hadn’t yet been invented.) The time when I would regularly cut calls short — even with my own mother — for fear that someone more important, career-wise, might be trying to reach me? (There was no call waiting. You had to pray that anyone who’d gotten a busy signal would try again and again. And not talk too long.)

Some survivors and observers longingly look back at eras like that as “a simpler time” and “a more personal moment,” but for a writer like me, it was actually a personal nightmare.

* * *

As a long-running journalist who’s often called upon to recreate past decades in the culture for articles and documentaries, I myself am not immune to falling into the old fogey trap of overly glorifying what’s dead and buried, while expressing dismay at the new and now. “In MY day…” is a phrase I studiously try to avoid, but I sometimes find it irresistible because I was actually in the middle of various pivotal scenes and lived to tell about them, and besides, in my day, things were newer to me, and therefore more exciting.

The first movie I saw was obviously more thrilling than the one I saw last night, and my first writing assignment was even more enthralling than this one (though I didn’t appreciate having to hand-deliver it in a storm). Holding onto that newness after all these years as a punishment against more recent developments is an easy landmine to step on because the past is safe and commodified. It’s already happened, so it can’t morph, or change course. It’s reliable and comforting, not reaching out to threaten or challenge you, especially since it’s vaguely distorted through the lens of memory.

Any displeasure one has with their current life tends to bring on exaggerated yearnings for the old days, mainly because what you’re experiencing now is vividly real, whereas what’s bygone is like a black and white movie that you can colorize at will. And in the process of remembering, we tend to erase with our own mental Wite-Out all the horrific aspects of old technology, like typewriters, which held us back. (I find myself doing this when a new editor asks for me to adopt the latest technology: collaborative editing in Google Docs.)

Seeing the past through rose colored glasses is an increasingly myopic process, especially as technology makes giant strides forward and former modes of communication resound with an astounding obsolescence.

One familiar nostalgia exercise happens when people — whether they were alive back then or not — lazily compare the best of the past with the worst of the present. In cases like that, the past will always win. Comments like “J.D. Vance can’t compare to JFK” and “TikTok videos aren’t as absorbing as Fellini films” are useless because they reduce contrasting eras to false equivalencies that hold no weight whatsoever. That said, if we can reverse the game rules for a second, The Zone of Interest is definitely better than Howard The Duck.

People also seem to nostalgically mist over about their college years, and I’m one of them, fondly remembering the bold new experiences, learning adventures, and group activities I had as a teen at Columbia College. What I usually edit out in my mind is the fact that I had chronic bad skin that Vaseline facials made even worse, plus I was painfully shy, experienced deep depressions, and had no idea what I was going to do once I graduated. This was my first time away from home, so I felt seriously disoriented as I was forced to grow up way more rapidly than I was comfortable with. I eventually made it as a gay gossip columnist, but back at Columbia, I hadn’t the faintest idea how I would end up paying the rent or if I’d survive at all. But when people ask me about college, I usually just say it was an eye-opening four years that expanded my mind and opportunities.

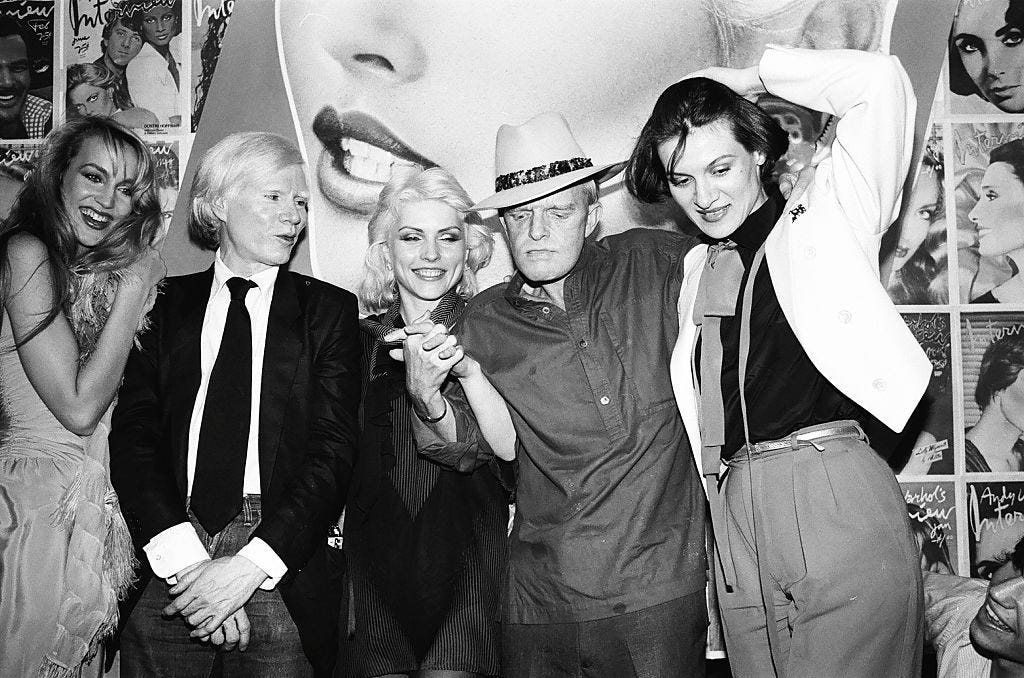

And then came the alleged glory days of American culture that I got to experience — the fabled past. New York City in the late 1970s is largely remembered as a time when the legendary disco Studio 54 attracted a glamorous crowd who danced and partied with abandon. I was lucky to be among the chosen few who got in (usually), but what most people forget is that disco arose as a hedonistic way to check your mind at the door and boogie into the night until you dropped. The war in Vietnam and the Watergate scandal had wrecked the public’s faith in the government, and New York was particularly bleak and ratty at this point, so people lined up to lose themselves for some mindless entertainment and line dances. It was tremendous fun for revelers — downstairs was the celebrity drug area, upstairs was a balcony for anonymous sex, and the main floor was for dancing — but nothing to really brag about, especially since the other denial-prone shtick in the air included “happy face” images and lame sitcoms like Three’s Company. Subtext often gets lost in the telling of history — only the sexy disco beat and fab outfits are recalled, not the dark motivations that they were a symptom of.

I came even more into my own in the 1980s, when I landed a weekly column in the Village Voice and found myself at the center of the burgeoning nightclub scene, filled with bohemians and artists. But a lot of those people were just using the scene to nab some press en route to mainstream success. I was one of their primary publicity dealers, so I was swarmed by fabulosities every night, but also by a lot of no-talent nightmares angling to cook up any way to nab a mention. The era of dazzling club “celebutantes” was also a time of yuppies, gentrification, ‘round the clock networking, and Madonna’s relentless, take-no-prisoners drive to make it big — an act of tunnel vision I witnessed up close (which is somehow now remembered as sort of endearing).

The big-haired era brought some deafeningly (expensively) bombing movies (Heaven’s Gate in 1980, Ishtar in 1987) and possibly the four worst sitcoms of all time: Punky Brewster (about an irritating moppet and an old man), Small Wonder (a robotics engineer passes off a charmless robot as his daughter), ALF (a wisecracking Alien Life Form that won’t shut up), and She’s The Sheriff (Suzanne Somers’ return, which made Three’s Company look like the work of Eisenstein.) In music, Phil Collins’ droning “Sussudio” was a low point, along with Bobby McFerrin’s chirpy “Don’t Worry, Be Happy” (which always managed to depress me) and the fraudulent schlock of Milli Vanilli, the pop duo who were as dubbed as Lina Lamont in Singin’ in the Rain.

Subtext often gets lost in the telling of history — only the sexy disco beat and fab outfits are recalled, not the dark motivations that they were a symptom of.

Even Broadway was in such a spiral that in 1985, three major Tony categories were eliminated because of the dearth of award-worthy talent on display. As for “the edge” that so many New Yorkers now miss so desperately, that didn’t only involve struggling artists doing their thing; it also included a lot of muggings and other crimes, along with a mounting AIDS toll, as President Reagan turned a blind eye, and fiery activism rose up to fight that. Going to those clubs where I would commune with both the icons and the nightmares was scary, since you had to constantly look behind you as you walked the streets, and in certain crime-ridden neighborhoods — like Hell’s Kitchen, where the streets were desolate and scary— you sometimes had to run faster than an Olympic sprinter.

Today, there are virtually no “bad neighborhoods” left in Manhattan. Today, the people who complain that New York has lost its edge generally either live in high-rise co-ops or moved to far-away cities where you get a terrace and a garage. And while Manhattan truly has become a place for rich people and chain stores, the edge has simply moved to other boroughs, like Brooklyn, where nightlife and performance art thrive thanks to better space and economic options. So, the old edge wasn’t all fabulous and the new edge isn’t all gone, but it’s easier for some to reduce all that to a nostalgic yelp of “I love the ‘80s!”

* * *

Two or three decades after any era, the culture tends to start aggressively looking back at that period, raiding cobweb-laden coffers in order to appeal to people’s memory banks and bank accounts. I’m often called upon to appear in docs about the ‘90s, but that decade — which brought us O.J. Simpson, Jonbenet Ramsey, Andrew Cunanan, John Wayne Bobbitt, the club kid murder, the Menendez brothers (who were apprehended in March 1990), Woody Allen/Soon-Yi Previn, and the Bill Clinton/Monica Lewinsky affair — is nothing to lust for that enthusiastically. Add then-NYC-mayor Rudy Giuliani’s assault on Manhattan nightlife as he Disneyfied the city, plus the ascent of reality TV, grunge, supermodels, and premium cable (making it suddenly OK for all my friends to stay home glued to the tube rather than hit the town), and I couldn’t wait for December 31, 1999.

Soon, it’ll be time for the inevitable aughts revival — in fact, already, in movies this year, we’ll see part one of a two-part screen adaptation of Wicked, the 2003 Broadway show that was a prequel to The Wizard of Oz, and also Gladiator 2, the followup to the 2000 Oscar winner about arena fighting in ancient times. That will be followed, of course, by a retread of the teens — when we’ll have parades in the street to commemorate the rise of important cultural icon Paris Hilton, as well as the emergence of the scintillating Kardashian clan, when in actuality they steal whatever brain cells are left in us after mind-crushing days spent reading Facebook posts about Adam Levine’s tattoos and Roseanne’s meltdowns. But I’m falling into the trap of putting down the present again. Let me stomp on those rosy glasses once and for all and rethink this with my own eyes. The truth is, we don’t only have the Kardashians, selfies, hash tags, and irritating “influencers.” We also have Greta Gerwig, Quinta Brunson, Colman Domingo and Taylor Swift. We have AI (which can be fun; admit it), The Last Word With Lawrence O’Donnell, drag queen standup comics, and air fryers.

Two or three decades after any era, the culture tends to start aggressively looking back at that period, raiding cobweb-laden coffers in order to appeal to people’s memory banks and bank accounts.

And while hookup apps may have helped eviscerate nightlife — because you no longer have to go to a bar or club to meet a partner — it’s certainly made romance a lot easier to navigate.

Any time I start fantasizing about being transplanted as an adult back into the 1960s, when there was peace, love, and mod fashion, I remind myself that it was also a time when gays could be arrested for holding hands, and there’s little chance that I would have flourished by just being myself. So the present is great! I’ve made it and I’m still here! Yes, there are horrid elements, but there always were and always will be.

Let’s agree to acknowledge that right now is the golden age of certain things (streaming, documentaries, diversity in entertainment, cross-pollination in cuisine), while a lot of yesteryear’s milestones — like “discipline,” smoking, and Lawrence of Arabia — weren’t really all that. And for those who loathe Donald Trump and as a result are suddenly looking fondly back at George “Dubya” Bush, let me remind you that you probably once protested that Dubya had invented the threat of mass destruction to involve us in an ungodly war. Remember??? Michelle Obama likes “Dubya” and Trump doesn’t, but that shouldn’t translate into Dems rewriting history and making him a belated hero.

Agreed? Now let me press “send” so I can deal with suggested edits in Google Docs.

This could be my favourite Oldster article yet. I lived in Brooklyn from 1979 - 1994. I read your column in the Village Voice with curiosity about who appeard in bold print and annoyance that I cared. You describe the 80s so well - the drive to be SEEN. I used to have nostalgia for the early 80s vibrant music scene, wishing I could go back to that experience with the way I feel in my skin now. But the lure of nostalgia is cloying and sticky and I appreciate the present moment I'm in, in a way that frees me to sometimes wander in memories when they arise, without wishing for a different reality than my present. The longer I journey in this life, the more untethered my relationship to time becomes.

I absolutely love this piece because I'm a nostalgia writer who disagrees with almost everything Michael says (while I admire his work.) I do miss my old typewriter, and actually have an Olympic manual in near mint condition. I started working in journalism in 1971 in high school in a paid position at age fourteen. However, and I wrote this yesterday, in looking at the past one will find the good, the bad, and the ugly. I recently interviewed a nostalgia expert for a magazine piece and she explains that the word nostalgia once meant a kind of mental illness. Who knew! I do think it is important to sweep the wheat from the chaff and every time period in history has both good and bad. Here's my piece FWiW https://amyabbott.substack.com/p/studying-the-past-is-fun