The Piggy 9 Show

Now in his 60s, Jay Blotcher recalls an alternative identity he created in fifth grade, the first of many “masks” he’s worn to try and belong.

Crafting masks for ourselves is often an act of both deceit and survival. I recall the first time I consciously created one for myself.

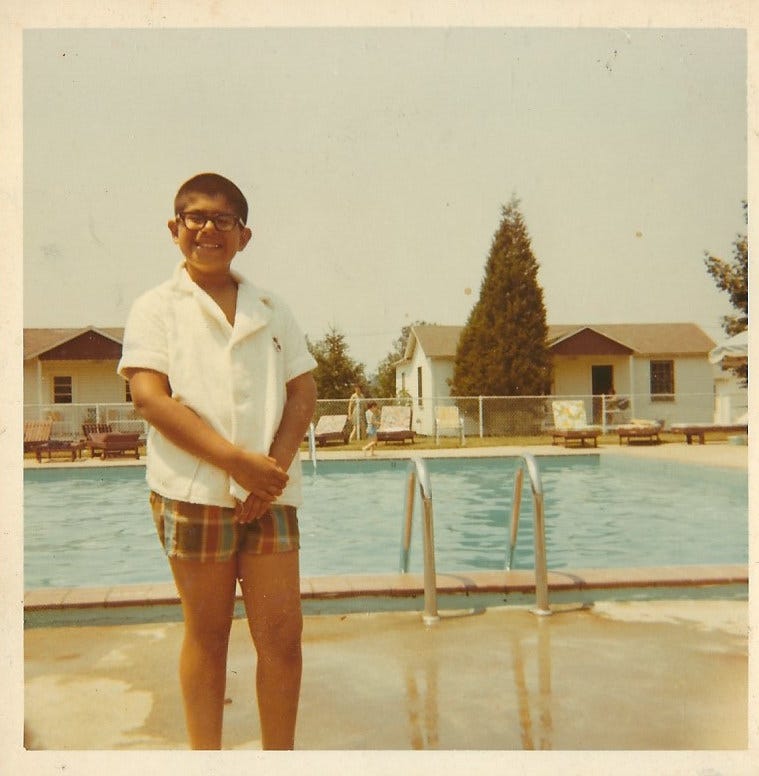

It was the spring of 1971. I was almost 11, a fifth grader at Martin E. Young Elementary School in Randolph, Massachusetts. To my chagrin, I was also a chubby, four-eyed, misfit.

I was made aware of my numerous shortcomings by classmates, who would helpfully remind me. Yes, I had thick glasses and Mom shopped for me in the “husky” department. Kids also called me “bald eagle,” thanks to the whiffle haircut (a crew cut without the brush top) I got every two weeks by Ralph at Sal’s Barber Shop. My hairdo made me look as nerdy as I felt.

Kids also teased me for my skin color. I was mocha-colored in winter and nut-brown in summer. I was 8 years old in Camp Peter Pan when I first heard the “n-word” aimed in my direction. It wouldn’t be the last time. I had been adopted and my birth father was Puerto Rican, a crucial puzzle piece I wouldn’t find until decades later. All I knew then was that I was darker than the other kids.

I was saddled with a mountain of personal defects, all seemingly unresolvable, making me an outcast. Joining Cub Scouts didn’t help me feel like I belonged. Neither did Little League. I tried a few months in each group, but remained unsocialized and miserable.

Admittedly, some things momentarily dulled the pain: DC Comics, Mallo Cups, and Dark Shadow cards, each pack with a stick of bubble gum. I got them at Gilroy’s QuikMart when I had saved up enough nickels. My confidence might have been in the gutter, but my collection of comic books and trading cards piled high.

I jumped up in the middle of English class to tell jokes stolen from MAD magazine. I scribbled grotesque cartoons on the blackboard…Soon, the kids who usually ignored me or hassled me laughed at my desperate performances…I decided my new hell-raising persona deserved its own identity. I called him Piggy 9.

Still, I hungered for friendship. Then I noticed that people on TV were adored by everyone. If I had my own weekly show, I thought, maybe I’d have friends. So, using my classroom as a soundstage, I reinvented myself as a TV star.

I jumped up in the middle of English class to tell jokes stolen from MAD magazine. I scribbled grotesque cartoons on the blackboard. I used the pencil sharpener to whittle pencils down to the size of birthday candles. Soon, the kids who usually ignored me or hassled me laughed at my desperate performances. I was encouraged.

I decided my new hell-raising persona deserved its own identity. I called him Piggy 9.

Piggy 9 was stitched together from bits of nonsense formed by my youthful neuroses. First, what could be a more rebellious choice of identity for a suburban Jewish boy than the unkosher pig? I added the 9 because it was my lucky number. I even created a Piggy 9 greeting: I pushed up the tip of my nose, gave a snort and an exuberant circular wave, then emitted a high-pitched “Hi!” I stole the “Hi” schtick from a recurring skit on the TV show Laugh-In. It was idiotic enough to be funny.

Piggy 9 was my alter-ego. (I’d learned the concept of an alter-ego from my piles of Superman and Batman comic books.)

My new mask not only fit snugly, it was quickly embraced by others. Soon, kids would greet me in the halls, pushing up their noses and squealing. They began to laugh even harder when Piggy 9 interrupted classes and terrorized teachers. So I upped the mayhem.

When my mom was alerted about my class clown behavior, she sent me to a therapist. Bruisingly, my appointments were at South Shore Mental Health Clinic in nearby Quincy. (“Mental” was Randolph grade school shorthand for “loser.”) I lied about my weekly visits, telling classmates I had started judo lessons. They looked at me with something that bordered on respect.

Kids also teased me for my skin color. I was mocha-colored in winter and nut-brown in summer. I was 8 years old in Camp Peter Pan when I first heard the “n-word” aimed in my direction. It wouldn’t be the last time.

In sessions at the clinic, I avoided explaining my reason for disrupting classes. Instead, I danced around the therapist’s questions. I played with finger paints. I crafted plastic flowers. I performed with hand puppets. The puppet shows always ended when I threw the performers against the wall—pretending they were the kids who loved Piggy 9, yet had no time for Jay.

To curry more favor, I gave Piggy 9 an extensive background story. Only in hindsight could I realize the reason for this overcompensation. Piggy 9 had tangible roots—because Jay Blotcher had none. All I knew was that I had been adopted soon after my first birthday. My parents told me all of this when I was very young—even before I knew what “adoption” meant. They told me to be proud of it. So at 5, I was strutting around the neighborhood, telling Larry and Howie and Janet and Cindy, “I’m adopted! I’m adopted!” in a sing-song brag, like I had a gold star on my homework.

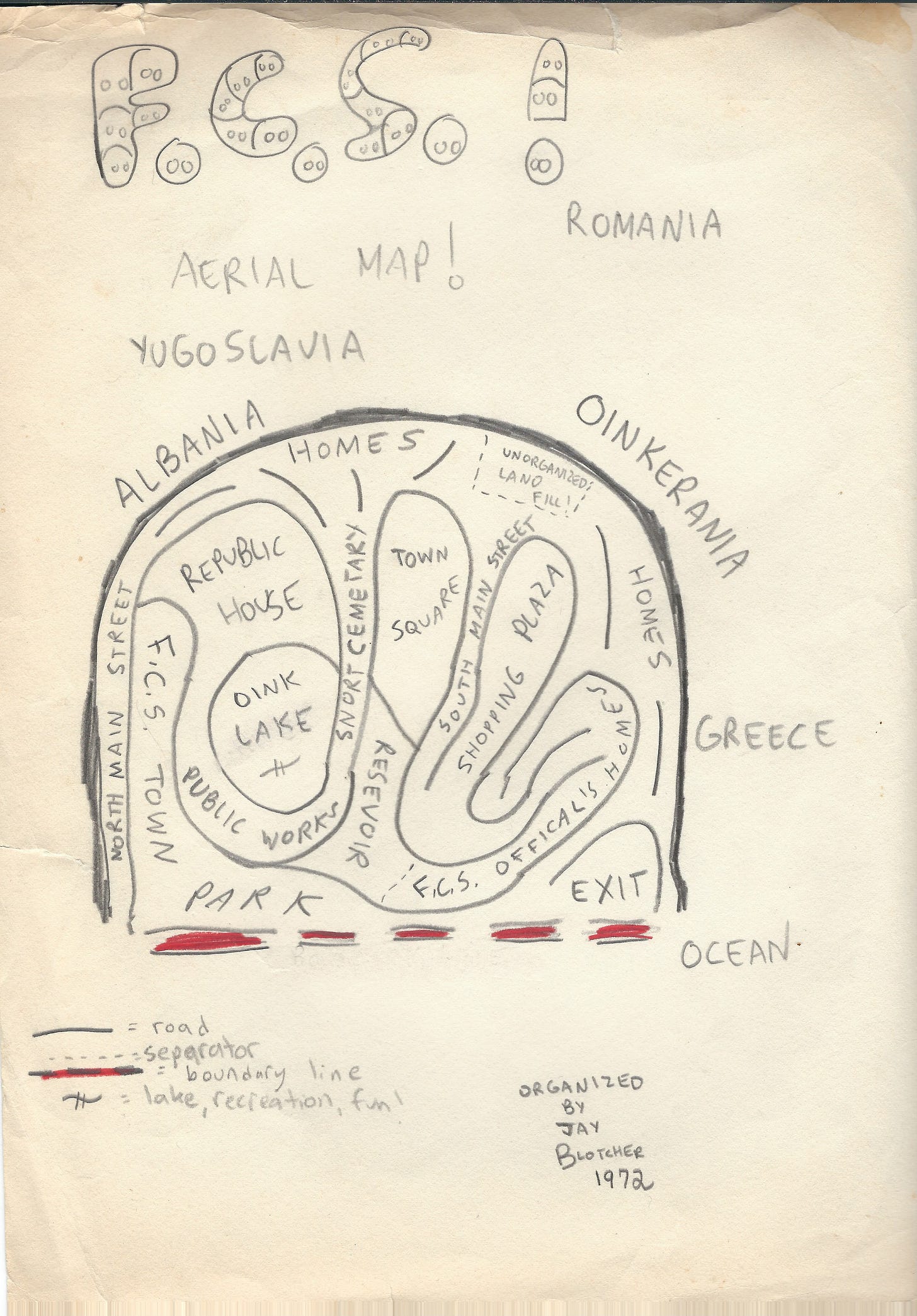

I told classmates the Piggy 9 origin story: He was a barnyard orphan, adopted by the Jones family, who ran the farm. His best friend was the father’s son, Frank Jones, also a fifth-grader. Piggy 9 had endured a tough life. Inexplicably, he had a unique set of enemies: Communists from behind the Iron Curtain. I scapegoated Commies because I had been effectively brainwashed by years of Cold War propaganda. I even sketched a map of the Commie headquarters, located on Flatnose Charlie Street in a fictional Russian country.

My crazy tales drew more attention. So I kept spinning them. It meant being held hostage by my “TV character,” but it was worth it. Kind of. Because while Piggy 9 was a star, Jay Blotcher remained a loser. Never invited to birthday parties. Passed over for bowling and pizza. Forget sleepovers and trips to Dairy Queen.

But if I ended the Piggy 9 Show, it would mean returning to obscurity. Even a half-assed popularity, I decided, was better than none.

Piggy 9’s notoriety grew. At recess, kids would gather to hear improvised sagas about their anti-hero and the Commies. I didn’t yet know the vocabulary word “cult” – but a cult is what I had unwittingly created, all from sheer neediness and chutzpah.

One recess, I decided to test the allegiance of my classmates. I yelled out “Piggy 9” and begin to march across the gravel, past the swings and the jungle gym. Without hesitation, Marci and Susan and Jimmy and Jeffrey and a few others followed in single file and echoed my cheers. They even added their own inventive touch: fists pumping the air.

I was giddy. But I also knew I was being watched by the cold fish-eye of Mrs. Proctor. She was the almighty recess monitor, tall, freckled and imposing , her sneakered feet planted in the middle of the playground, her face frozen in a scowl.

One morning recess, I asked Susan to do something to honor Piggy 9. She hesitated too long, so I grabbed a hank of her beautiful chestnut-brown hair and pulled. I tried to do the same thing to Howard but he had short blond hair and could run faster than I. In fifth grade I learned a very adult truth: that absolute power corrupts absolutely.

Despite my clumsy quest for power, my followers still followed me.

Piggy 9 had tangible roots—because Jay Blotcher had none. All I knew was that I had been adopted soon after my first birthday. My parents told me to be proud of it. So at 5, I was strutting around the neighborhood, telling Larry and Howie and Janet and Cindy, “I’m adopted! I’m adopted!” in a sing-song brag, like I had a gold star on my homework.

It was soon the fall of 1971. I was in sixth grade. So was Piggy 9. And he was still disrupting classes, still leading playground parades.

Finally, Mrs. Proctor decided enough was enough and marched up to the principal’s office. I learned that day that grown-ups could also be tattle-tales.

Principal DelVecchio had a terrible temper. When he saw kids misbehave, his face turned cranberry, roiling beneath a shock of brown-grey hair slicked back with Brylcreem. He continuously patrolled the hallways, limping from a war injury, his eyes ever-searching for bratty students.

I had been in Mr. DelVecchio’s office before. It was for disobeying Mrs. McNamara, my third grade English teacher, a haughty Irish woman with flashing blue eyes and dark-brown curls. I didn’t kiss her ass like the other kids. She hated that. She sent me to the office twice for sassing her. Twice, Mr. DelVecchio delivered the penalty: three slaps to my open palm with a heavy wooden ruler reinforced by a piece of steel that ran its length. The ruler made my hand as red as the principal’s face.

When Mrs. Proctor informed Mr. DelVecchio of my playground antics, I was once again called down to the office. My stomach burned as he eyed me up and down. But this time, I didn’t receive the kiss of his ruler. Instead, he called home and told my mom how Piggy 9 threatened everything that was good and decent at Martin E. Young School.

When I got home that afternoon, Mom announced, simply, “We need to talk,” and led me to my bedroom. I knew this would be serious. One, because she was eerily calm, and two, because she was carrying her golden pack of Benson & Hedges 100s and favorite ashtray.

Between puffs, she told me how the principal’s call had upset her. Then she asked me with open disdain: “Who is Piggy 9?” I struggled to sound casual as I told her I was just having fun. That the other kids liked it.

Mom listened and then stubbed out her third cigarette. She narrowed her eyes and informed me that this Piggy 9 business had to end. “Or,” she added, “do you want to go back to therapy?” She exhaled a plume of smoke that said, I hope we understand each other. Then she went to make dinner, lamb chops with mint jelly, leaving nicotine clouds in my room.

Alone, I brooded. Mom probably thought her request was simple. But she had no idea that ending my “TV show” would tear a hole in my soul. Then my desperate sixth-grade mind hatched a plot. A genius plot, since it would both obey Mom and defy her. Piggy 9, I vowed, would depart in a blaze of glory.

The next day was November 17, 1971. A Wednesday. I ate my usual breakfast: a toaster-oven cinnamon-pecan pastry, melted butter seeping into all its swirls, my milk in a Bozo the Clown jelly glass.

I decided to carry out my master plan in the late morning—in Miss Conrad’s English class. I quietly handed a pre-written note to Bruce. He read it, gulped, then passed it to Ellen. She passed it to Jimmy, and Jimmy to Gail— until most kids in class had seen it.

And that’s how my sixth-grade class learned that Piggy 9 was dead.

He had been driving home the previous night when his car suddenly went off a cliff. Authorities examined the burning wreck and found his brakes had been tampered with. The evil-doers? The Communists. The note was signed by Frank Jones, Piggy 9’s stepbrother.

As I navigated through life, I still wore an array of masks. But I did so with less fanfare, more subtlety. One elaborate mask I donned was to hide being gay. It took years to discard it. Attaining a measure of self-esteem (losing my baby fat and getting contact lenses helped) made it easier to attend class reunions years later.

My classmates rose to the occasion admirably; they assumed looks of shock. I was thrilled. By killing off my creation, I had only deepened the Piggy 9 legend. Throughout the day, kids handed me handmade sympathy cards, made from notebook paper. Steven, the smartest kid in class, created a card on manila oaktag. When you opened it, a Piggy 9 head popped up.

That evening through clenched teeth, I told my mother the news; I’d killed off Piggy 9. She shrugged, as if I had just obeyed her request to take out the garbage.

The next day, the wounds of loss among classmates remained fresh. They all had the same question: Will there be a funeral? I couldn’t refuse my cult’s final request. I spontaneously announced a burial the following day.

At Friday morning recess, I led a dozen classmates to a far corner of the playground. I pointed to a make-believe grave at their feet. They pretended to appear bereaved. Inspired, I made up a eulogy on the spot. About what Piggy 9 meant to all of us. About how he fought for what was right. About how his murder by the Commies on Flatnose Charlie Street had to be avenged.

I was almost 11-and-a-half and speaking at my own funeral.

But the service was interrupted. A bunch of kids suddenly barreled into the mourning circle. These were the toughies: kids with ratty clothes and extensive detention records. My mourners suddenly dispersed. I was alone. The tough kids poked me, demanding to know what was going on. I stammered an explanation. But a make-believe funeral for a make-believe pig sounded “mental.” They laughed in my face. The poking escalated. I knew that punches would be next. So I ran away, whining that I was going to report them to the principal. Instead, I hid until the recess bell rang.

The Piggy 9 Show was over. Eventually I realized that was okay.

By high school, I learned to make friends—by just being me. It couldn’t match my earlier TV-star popularity. But it was good enough.

As I navigated through life, I still wore an array of masks. But I did so with less fanfare, more subtlety. One elaborate mask I donned was to hide being gay. It took years to discard it. Attaining a measure of self-esteem (losing my baby fat and getting contact lenses helped) made it easier to attend class reunions years later. There I laughed and reminisced with people who once chipped away at my fragile ego.

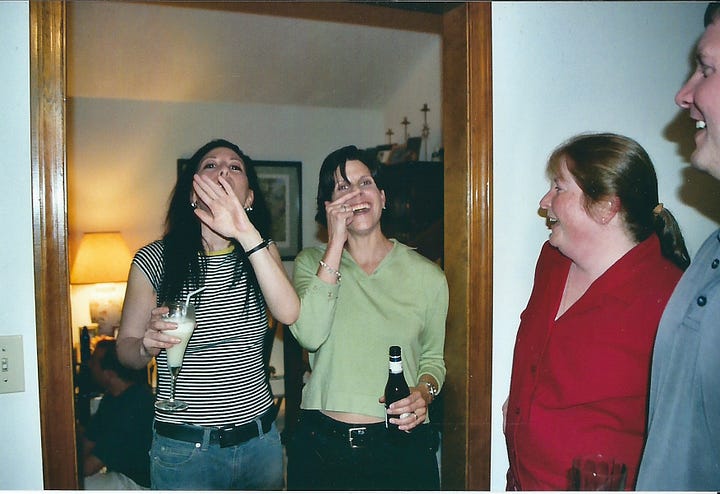

In 2003, I attended a 25th year Randolph Class of 1978 reunion. At one point, I began snapping photos. Marci and Susan, both Martin E. Young classmates, posed for a shot. As my camera flashed, they both tugged up their noses and offered the Piggy 9 squeal.

It's amazing how someone else's story can sometimes take your breath away because it's so similar to your own.

My alter-ego was Super-Piggy because EVERYONE called me Piggy, including my middle school teachers. I started making up stories about a pig who wore a cape and saved people. People loved them. I gave my stories away to a popular girl, hoping to make a friend.

I am envisioning Jay's childhood reminiscences as a movie directed by Taika Waititi. And then all the kids who excluded and/or tormented him have to read the rave reviews and watch the interviews and see him on the red carpet at the Oscars...