The Nine-Page Letter to My Daughter that's Really for Me

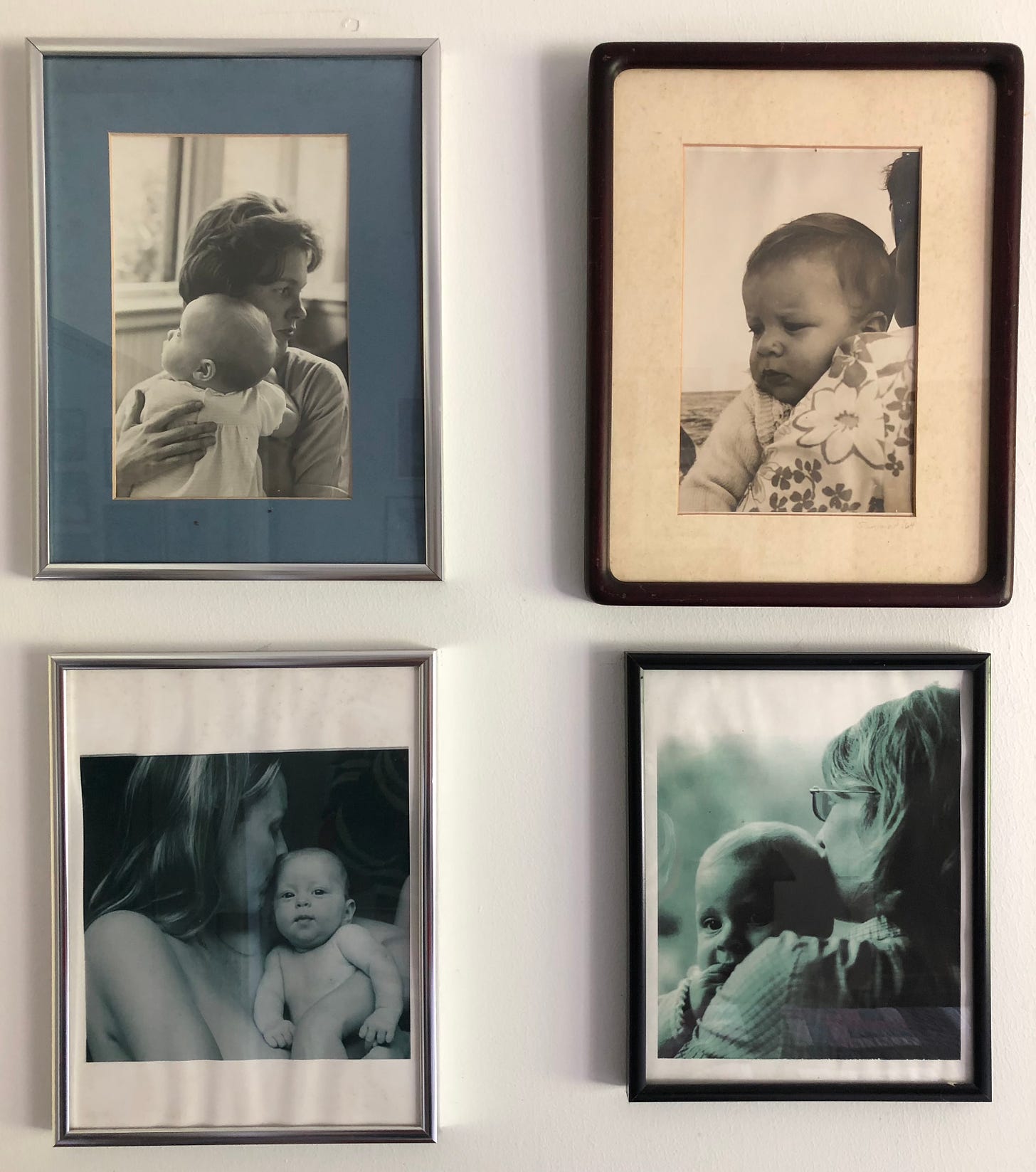

With her daughter at college on the other side of the country, Ann Faison confronts her empty nest.

I carefully wipe my dripping nose before writing, lest my daughter receive yet another tear-stained missive from me. I've been crying, but I won't let her know that this time around. With her freshman year of college behind her, my daughter is finding her footing on a small campus in Vermont and needs less support from me. This is great. Paradoxically, it also hurts.

I swear no one tells you this stuff. Just like no one tells you about the dangers of childbirth, no one dares break the news that when the time comes, letting go of your offspring will entail serious grief.

Why? I wonder. Didn't I already go through this last year, when she first went away to school? Aren't I done yet? But as with all grief, I’m impatient to be through it before I've really begun.

I swear no one tells you this stuff. Just like no one tells you about the dangers of childbirth, no one dares break the news that when the time comes, letting go of your offspring will entail serious grief.

Last week I sat in my therapist's office talking about my mother. "I wonder if she ever felt this way?" It was something I'd never considered and I immediately felt guilty about that. Because my mother died of breast cancer before I started high school, she wasn't there when I went to college. But two of my older siblings had already left home by the time she died, so I wondered if she had felt this bad when they left? And then the next thought: What was it like to send her oldest children off to school as she was reckoning with her mortality?

Perhaps this is why I felt so sad, the therapist suggested. Maybe because my youth was framed by loss, I will always feel bad watching my kids navigate their separation from me. Even though I'm here, and healthy, my ties to them feel tenuous. The only time I fear for my safety is when I pull out past my suburban front lawn to race down the gritted teeth of the city. And yet, I feel how thin the umbilical cord between me and my far-flung daughter has become and it startles me. Like a fine pencil line, thin as spider's silk, stretching across the country.

When my mother died, even though she was sick with cancer for years, I had no idea what was coming. No one can prepare you for your mother’s death, especially when you're barely old enough to understand that people do, in fact, die.

Because my mother died of breast cancer before I started high school, she wasn't there when I went to college. But two of my older siblings had already left home by the time she died, so I wondered if she had felt this bad when they left?

I feel similarly blindsided by my daughter's absence. I always thought being motherless would protect me, somehow, from this particular brand of grief. That it would give me a certain perspective that would help. Not so. I miss my daughter even more now that she feels increasingly at home on campus. She no longer calls when she’s sad or hurt by something that happened with a friend. "I feel really supported here this year," she says confidently into the phone after her first month. My heart simultaneously soars and crashes. It’s everything I want for her. And it’s crushing. It turns out, the departure of children, even their natural fledging, is sharply painful. Perhaps, as the therapist suggested, this is especially true for someone who grew up motherless. And my blindness to that is stupidly familiar.

I was not close to my mother when she died. Her illness scared me. As she got sick, I was navigating middle school, wrapped up in my social life and fitting in. There was nothing "normal" about a mother who was ill. Consequently, I spent my free time at friends' houses, busily ignoring my mother's deteriorating mood and health as she became increasingly quiet, immobile, and bloated with steroids.

I never said goodbye, and it took me years to let go of that. Eventually, I had to forgive her for not forcing a conversation with me as she was dying. She knew I refused to see the truth, but she was not one to say, "Hey! I know you don't want to talk about this. But you'll regret it later if we don't." She could have written me a note, but she didn't. I think she was depressed. And like some depressed people, I imagine she might have thought we'd all be better off without her. She worried her illness was a burden on us. She manically discarded her possessions, as if even her stuff would weigh us down. I have no idea what her thought process was. Perhaps she felt so guilty about leaving us, she couldn't bear a goodbye. Now I understand how hard it would have been.

I always thought being motherless would protect me, somehow, from this particular brand of grief. That it would give me a certain perspective that would help. Not so.

My instinct as a motherless mother was always to aim for closeness and honesty. I tell my kids when I’m sad and share many of my deepest feelings. I’m open with them about my early grief experience and encourage them to honor their own emotions by expressing them honestly. I cherish my time with them, cognizant that we never really know how much we have left. And I've never promised to “always be there,” at least not in the flesh.

I’ve always felt my mother’s presence in my life, but she is no ghost. She doesn't bang pots or slam doors. And she doesn't strike me as angry. But sometimes I wonder if she experiences longing and is somehow trying her best to be a mom from the place of nowhere.

As a mother, I know my job. I hold back from sending my daughter too many texts. I try not to check Instagram for her posts or over-comment on them. She senses it and reaches out, charitably. Of course, I want her to find her own security. I do. But my heart wants to reach, stretching hands and fingers cross-country to touch her face. Instead, my heart has to settle for tapping on keys. I miss her every day. I miss my old job of taking care of her. Being her everything when she was little and her guide as she grew already feels like a memory I could have made up.

Now it's time to weave a new cloth, as the old one comes apart in my hands. The edges frayed as the college girl dances across the wood floor of a studio in Vermont, and I bake in my car, driving the California freeways.

I was not close to my mother when she died. Her illness scared me. As she got sick, I was navigating middle school, wrapped up in my social life and fitting in. There was nothing "normal" about a mother who was ill.

One remedy is writing by hand; one of my oldest comforts. I take a pen from my desk drawer and write a long letter on paper. For nine pages I share the news of home. I tell her about the cat's visit to the vet. About replacing the plant that she forgot to water over the hot dry summer. I write about extended family and her younger sibling. I write about a bar I want to take her to when she turns twenty-one. Writing dull letters is what my mother did when I was at summer camp, and I still have those letters. Even though the news was never exciting, I loved seeing my mother’s handwriting, and hearing her voice, as it were, scrawled across the page. And now, writing to my very grownup daughter, I find relaying the daily happenings of life without her puts my heart at ease. A small voice in my ear whispers, she'll be back. It will never be the same, but one way or another, she'll be back.

Thank you for this lovely piece. I write as an 85 year old woman preparing to (eventually but not immanently) leave my daughters who are 62 and 65. Many of their behaviors towards me echo your careful choices about how much is enough contact, disclosure, confidences? What is the balance they need to strike now that I am old and theyrre in late middle-age.

This is a different time, of course and your mother didn't live in a world with death doulas and the knowledge of grief that you write about so well. Ours was amore inchoate time to figure out how to die and leave your beloveds. Now there is information, resources, groups everything to help the novice leaver to leave well.

I too wept when my girls went off to college. It was a profound ending of how we were together. But over these intervening forty years, there have been other endings, other ways of being together. I think I have concluded that endings are folded into every part of our relationships with our daughters. Mothering. Grandmothering. Navigating their mid-life fears, menopause, deaths of their contemporaries. Everything they need their mothers for. It keeps changing, morphing.

May you cherish the unfolding.

I promised I wasn't going to cry. Who was I kidding? This is the sentence that undid me. You put into words exactly what I've been feeling with these sentences: "I miss her every day. I miss my old job of taking care of her. Being her everything when she was little and her guide as she grew already feels like a memory I could have made up. " Thank you.