The Joy of Living—and Writing—the Truth

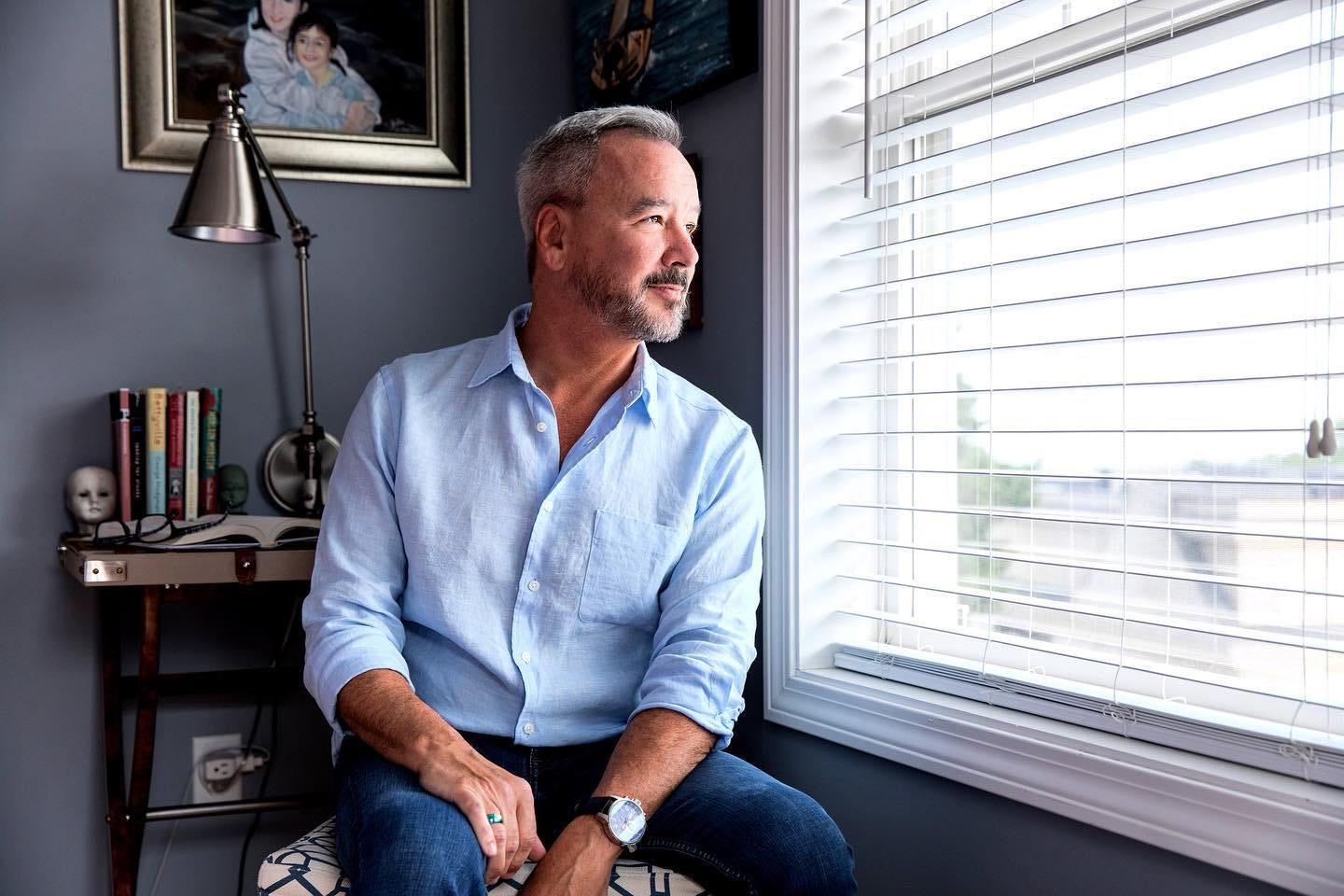

On the brink of 60, William Dameron reflects on the happiness borne of coming out at 43, and publishing his memoir about it in his late 50s.

We were sitting on the terrasse of L’Aigle Noir bar on a summer evening in Le Village, the gay neighborhood of Montreal, when I told the stranger I had recently published a memoir. Through polite banter, I learned he was an English professor at a small college in Pennsylvania. In front of him was a half-full glass of amber-colored beer, a few sheets of paper, and a rainbow-colored book with a pair of reading glasses resting on top.

“What prompted that?” he asked.

He was conventionally handsome with blue eyes and graying hair parted neatly on the side. I surmised that he was a couple of years on either side of my age, 59. He was gracious, immediately offering up the three vacant chairs at his table to my adult stepdaughter, her work colleague, and me. Initially, I declined the offer, having been raised as a good southern boy who refuses, to a ridiculous degree, to inconvenience others, and perhaps more so because I was leery that my acceptance would be construed as an invitation for more. But now, I found myself in the uneasy position of desiring a stranger’s praise instead of his questioning. I have been asked multiple times why four years ago, at 55, I published a memoir, without exception, always following a compliment. You wrote a book? How incredible! What’s it about?

However, the professor did not congratulate me or ask for my name or memoir title. His question was direct, and to be honest, I did not know if he was asking why I told him or if he was questioning the motivation behind the hard work of writing a book. I decided to go with the latter.

“Because I couldn’t find my story published anywhere in the world.”

I have been asked multiple times why four years ago, at 55, I published a memoir, without exception, always following a compliment. You wrote a book? How incredible! What’s it about?

It was a practiced answer. An old reliable I have used in interviews and readings, and I could tell from the smirk on his face it was one he had heard before and perhaps did not fully believe—Toni Morrison be damned. He could not have known that the ability to sit with him in that time and place without experiencing crippling shame took most of my adult life to accomplish. Nor could he have known sitting with him at that table had meant destroying, at 43, everything I had built, and reconstructing it in a way that finally made sense after I married my husband at 47. Before I could explain, a group of young women laughing and pointing paraded by on the pedestrian street, one of them wearing a white sash and an abbreviated bridal veil. They wore short, colorful summer dresses that fluttered in the perfumed breeze like a flurry of red, yellow, and green flower petals.

“The woo girls,” he sighed with an expression that matched the smirk he had previously displayed. “They’ve come to visit the petting zoo.”

After a lifetime of peering from the outside in, it is often a surreal experience to find myself on the inside looking out. I was a stranger for most of my life, pretending to be someone I was not. Of course, the world is full of pretenders. What made my story so unique that I felt compelled to put it down in words? We don’t need any more coming-out stories. This was a common response from agents, publishers, and “book experts.” In fact, one person who called himself the book doctor told me my writing was nothing special and the subject matter unimportant. I thought you should know, so you don’t waste more time. At 52, five years after I began writing my story, I quit.

I did not know if he was asking why I told him or if he was questioning the motivation behind the hard work of writing a book. I decided to go with the latter…“Because I couldn’t find my story published anywhere in the world.”

Like the woo girls, I remember once being able to walk into a room and sense the power of attraction generated by my youth, though in those days I knew I could never use it in a way that would satisfy me. In their presence, I briefly envied them for their radiance and confidence, and the handsome young men with their swagger, too. The young gay men in Le Village possessed a confidence that I never had, or could exhibit at that age. I questioned aloud the odd tradition of bachelor and bachelorette parties, one last night of debauchery with their “Woo” rally cry, before committing to a partner as if it were a life sentence instead of a lifetime goal.

“And as you know, most sex is forgettable,” the professor added.

I did not know this.

I have had sex with a handful of people and, depending upon the definition, have only been truly, deeply intimate with three: my college girlfriend, my ex-wife, and my husband, in that order. Perhaps there were individual lovemaking sessions that have faded into obscurity, but I have never forgotten the people.

“Back home, I might be the attractive one in a sea of men, but every other man here is beautiful,” the professor lamented.

This I knew. But was their beauty derived from symmetry or youth? I decided to go with the latter, though it could have been both in many cases. When I came out in my forties, I had missed the window of opportunity to employ youthful beauty to my advantage. I never participated in forgettable sex, though some of my partners surely have forgotten me.

After I gave up writing at 52, I made one last ditch effort. It was a long shot, and I decided the answer—to be published in the New York Times,—would determine my future as a writer. I reduced a single chapter of my manuscript to 1500 words and sent it to Dan Jones at the New York Times Modern Love column. In that essay, I recalled the handful of people with whom I had made love while my ex-wife gave me a final haircut after a marriage of twenty years dissolved. It was not a typical Modern Love essay. It was, like me at the time, unresolved.

In their presence, I briefly envied the woo girls for their radiance and confidence, and the handsome young men with their swagger, too. The young gay men in Le Village possessed a confidence that I never had, or could exhibit at that age.

There was a lull in the conversation with the professor, not unpleasant or awkward. A moment to appreciate the strip of orange tinging the edges of the deepening blue sky, the beads of condensation collecting and rolling down our glasses, and the whiff of musky cologne from a bearded man with tattooed arms who cast a lingering glance as he passed. It was a moment that was remarkable or unremarkable depending upon which side of the table you sat. I nodded to my stepdaughter and her colleague, stood up to go, and offered my hand to the professor.

“I’m William.”

He titled his head, smiled, and, shaking my hand, gave me his name. He would not get a more detailed explanation as to why I had written a memoir, and perhaps he did not care. Nearing 60, I have found that not everyone needs or wants to know my whole story.

Would I have continued to write if I had not received that short acceptance email after three months of waiting for a response from Dan Jones? I’m interested in your essay. It is difficult to say. None of us, other than time-travelers and clairvoyants, can know the future, and most of us have difficulty making sense of our past. Rounding the corner of my sixtieth year, I have learned something. Joy is always experienced in the present. Anticipatory joy, planning for a night out on a summer evening, waking when a strip of yellow illuminates the morning sky to write a few pages of a book, and carrying the kernel of hope in your heart that one day you will love someone body and soul can be just as satisfying as the end result. Joy is always present, and experiencing it is never a waste of time.

Rounding the corner of my sixtieth year, I have learned something. Joy is always experienced in the present.

Outside now the sun is shining, a few white clouds drift through a background of heavenly blue, and my husband jumps on the scooter we call “Summer” because of its brilliant orange hue, and heads toward the beach on our southern coast of Maine. Here I sit, putting these words on a page. There is only one way to become a writer, and you must never let anyone take that away: You write. I cannot say why others do this, but at almost 60, I have come to know what prompts me.

Joy. Pure joy.

This is one awesome read. I loved reading it and did not want the piece to end.

Joy is always experienced in the present. Lovely and worth remembering. Thank You