The Inside Story

Carolita Johnson examines some of the inner workings of a woman’s body from puberty to menopause.

The subject of my pre-doctoral studies was medieval nuns and their relationship to their menstrual cycles. Long story short: my theory was that this relationship was determined by the very real divide between the early Christians who favored either the Old Testament or the New Testament on the inherent “sinfulness” or absence thereof of the human body. The traditional, Old Testament attitude that menstruation made women “unclean” somehow prevailed. Fancy that. Call me crazy, but I had to believe that the way the Church, the Patriarchy, and all of society saw women’s bodily functions had an effect on women’s relationships with their bodies.

Stories of menstruating women ruining mirrors they looked into, or causing soufflés to fall, causing farm animals to miscarry, mayonnaise to “not take,” etc., and menstrual blood used as an ingredient in cures for leprosy or magic potions, were common. But even if they were all but forgotten by modern times, they merge easily into my being taught, in the 1980s, to call my period “The Curse.”

I’d noticed, in many hagiographies, that one of the first signs a woman might be a saint, besides experiencing ecstatic “visions,” was that she’d barely, if at all, need to eat or drink anymore, and her various bodily secretions would cease. I wondered if nuns might be using herbs, self-starvation, and/or physical exertion to put an end to their secretions, amongst which, their periods.

Compare this to how, in modern times, many women, including myself, would use The Pill without the classic 7-day pause in dosage to skip an inconveniently timed period. This pause was designed to give women on the Pill a “period” that was more symbolic than functional, almost more of a superstition, and totally unnecessary, medically speaking. Recent years have even seen the introduction of contraceptive pills actually designed to limit a woman to 0-4 periods a year — hormonally inducing amenorrhea, or absence of menstruation. There are times when women want to avoid having their periods, for example, during vacations, sports events (with the notable exception of Kiran Ganhi), honeymoons; in other words, times when we want to be at our best and free of physical impairments or, let’s be frank: free from the anxiety of being discovered menstruating. Some of us opt to be free from that anxiety year-round now. I think medieval nuns would have loved to have that option.

The possession of a female reproductive system therefore involves a certain amount of effort and planning, in both practical and social/emotional terms; in other words, work. I’d always wished I could find the story of one woman’s life and at least one key bodily function in one place, maybe one for each century. No such luck for my medieval research. I had to glean a bit here, a bit there, in letters, anecdotes, superstitions, confession manuals.

This is why I decided, here, to describe the life of one woman, me, in the context of one reproductive system, mine, from about 1970 to 2018. Writing about my body and its maintenance during my two odd quarters of the 20th and 21st centuries in the “free world” directly connects me to women who lived over a thousand years ago; women who lived and died before me, and sometimes, indirectly, for me.

This essay is my offering to you, dear reader from perhaps beyond 2019, wearing “Thinx” menstrual panties, which I never got the chance to try out before menopause. Or to you, future reader, who never heard of Thinx because they’re already obsolete, replaced by something even more amazing, you, who chanced upon this article by a word search, perhaps “20th and 21st century menstrual products” or “21st century birth control.” Hopefully you’re not reading this in a moldy paperback anthology in the crepuscular light of a post-apocalyptic landscape, astounded to learn that sawdust on the floor, isolation in a tent, or being employed to exterminate caterpillars in crops by walking around menstruating with your skirts up used to be things of the past.

According to Pliny, a menstruating woman, when led naked around the orchard, protected it from caterpillars, and this belief was acted on as late as 1927.

For context, my body is largely unremarkable. I was born with no disabilities or diseases in the mid-1960s, into the American Middle Class, to a second generation American father and a South American mother, a recent immigrant. I knew where babies came from before I was 10 because my father, who was on the autism spectrum, had answered my question frankly, but still delicately. I wasn’t ignorant or living with the delusion of baby-courier storks or cabbage patch births.

Nevertheless, not long after needing deodorant marked the awakening of my female reproductive system at around 11 or 12 years of age, a seemingly horrible thing happened that I was completely unprepared for because it wasn’t something anyone ever talked about. I began to have a slight vaginal discharge, something I’d never had before, and which I assumed meant that I was dying, rotting from the inside. I waited and prayed for it to stop, or for death to come. But neither happened and my fear was a silent, ongoing torment, keeping me awake at night, keeping me distracted during the daytime. I would check again and again to see if it had stopped, only to be devastated that it hadn’t.

I finally went to my mother for help, something I was rarely inclined to do since we didn’t get along at all. I burst into convulsive tears as I told her there was something wrong with me. She laughed in relief when I told her what it was, and explained that it was normal, that it only meant I was growing up, and that the discharge would always be present in some degree as an indicator of some kind; it would change consistency when my period was coming and when I became pregnant someday, for example. I would basically leak stuff all the time, is what I understood, corroborating my theory that becoming an adult was like going bad from the inside.

Just when I was resigned to this memento mori in my panties, my budding breasts started to itch like the dickens: small comfort that they didn’t smell bad, too! We all know what came next, though I wasn’t expecting it for a few more years. When I was 13, riding my bicycle back home from looking for horseshoe crabs and eels in the bay next to the expressway with my best friend Joyce, I began experiencing abdominal cramps which I thought were just a stomach ache or a need to poop. When things began to feel urgent, we made a detour to find a public bathroom.

I closed the stall door, pulled my panties down in the stall and saw…chocolate? What in the world? How? Was it poop? My god, I hoped not. I smelled the stain, and identified it as blood. “Well. I guess this is it,” I thought grimly recalling passages of Judy Blume’s Are you there, God, it’s me, Margaret, “my period.” I did the thing every girl knows to do instinctively: I wadded up a bunch of toilet paper, sandwiched it between my labia, pulled my panties up into a wedgie and hoped for the best as we rode home.

When I got home, the wad had wandered (as every young woman learns a wad of TP will do) way up to the backside of my underpants; my first lesson in menstrual ergonomics. I found my mother’s stash of “Kotex” sanitary napkins but had no idea what to do with the long tabs at top and bottom (before the innovation of adhesive strips, women used safety pins to anchor them to their panties, or wore a special “sanitary belt” that held onto the pad tabs from around their waists). I helped myself to more as needed for the next few days.

Menstruation completely changed my relationship to time and space in our world. By my second period, I realized napkins were uncomfortable, impractical, annoyingly bulky, and possibly smelly. (Again with the smells!) I was haunted by the words of that awful summer camp song: “You can tell by her smell she isn’t feeling very well, as her time of the month rolls along.”” Did I smell?

Hiding the fact that I was menstruating became a monthly, five-day long, overarching preoccupation. Wearing a long, butt-covering sweater or jacket was one way to be free of the paranoia that people were observing and about to mock me for a tell-tale bloodstain or an unsightly bulge in the back of my pants. “Maxi pads,” as they were known, were truly “maxi” back then, and as if trying to hide the fact you were wearing one wasn’t enough of a challenge, getting rid of a used old-school maxi pad was like getting rid of a small corpse.

I’d roll the pad up as compactly as possible (about the size of a softball, as I recall), shove it deep into my parents’ alarmingly small (or worse, empty) bathroom wastebasket, brush some trash over it, then hope it wouldn’t unroll, yawning and stretching back out to its full length, almost a foot long and at least half an inch thick before modern technology did womankind a favor and made them much flatter and ergonomically shaped a decade later.

I’d sit at dinner worrying that the next person to use the bathroom might be a male relative or friend who would discover it and accuse me, mock me, humiliate me. My relationship to my discarded maxi pad was not unlike Macbeth’s and the gory ghost of Banquo.

It was therefore a big moment in my womanhood when I turned to “Playtex” tampons. Tampons could be flushed down (most) toilets. I didn’t like the plastic applicator, which seemed wasteful and also creepily phallic, so I switched to non-applicator “O.B.” (which stands for “ohne binde” or “no napkin,” in German) tampons.

The very name evoked the no-nonsense, “get over it, it’s a physiological function” attitude I sought, in contrast to the shame implied by the name and pink “Playtex” box that willfully disguised tampons as innocent, girly powdery-pink fun that didn’t involve touching your own blood or vagina. I was irked by the negation implied in the “-ex/-ax” in the brand names, “Playtex” and “Tampax.” They seemed to imply they were making my period magically disappear, stamping a big “X” on the entire biological process: “Your period? All gone!” Using O.B. tampons required using a finger to insert them, providing an opportunity to understand and own the landscape of my vagina, which would no longer be a disembodied mystery zone “down there.”

Tampons also soon defined the limits of the overlap between my mother’s body’s journey through womanhood in the Western Hemisphere and mine. She couldn’t understand how tampons (or, seemingly, the vagina) worked:

“How do they stay in?,” she asked, “How do you get them out again? What if it gets lost inside? Won’t you lose your virginity? Do they pop out when you cough?”

I deemed my mother to be suspiciously unforthcoming if not irresponsibly lacking in information about the way the female body functioned. I never asked her anything about my body again, preferring Judy Blume novels and “Our Bodies, Ourselves” as reference material. “You don’t know anything about anything,” was not just a random slogan of teenage rebellion. This generational chasm, which wasn’t just our own, began with matters of life and death: valuable knowledge around the means of reproduction.

My reference library.

My period management choices were part of my rejection of my mother, who I perceived as a representative of a pre-Feminist, old school of submissive and willfully ignorant womanhood which idealized motherhood, and which I thought I was turning my back on for the rest of my life. Like many other teenage girls, I rejected my mother because (among other, more complicated reasons related to our very different personalities and mental health issues) it was easier at the time than standing up to an entire social order.

The joke was on me for not realizing that media in all its forms, as well as ordinary social pressures, would continue to do almost exactly what I perceived she was trying to do.

Meanwhile, my period was heavy and unbelievably painful till its last year, forty years later. I mention this not to give you “too much information” (something we women are often accused of doing when talking about the bodily functions of a good portion of the population and workforce) but because their relevance reaches from my acute menstrual cramps back in 1980 far into reproductive rights and healthcare budgets being reconsidered every time a new judge is to be appointed to the Supreme Court of the United States.

During the first year of my monthly period, day one of each would find me doubled over with pain in bed, waiting for my father to come back from the drugstore bearing “Midol” (acetaminophen with caffeine and a bit of antihistamine, to treat bloating and water retention). I couldn’t tell if it was really working: my menstrual cramps would eventually subside when my period was almost over, with or without help. I learned to get used to the pain,learned not to twinge or wince in public at the cramps, learned to recognize that overstuffed feeling and the little air bubble trying to escape my inner labia that indicated my tampon was saturated and about to leak (and in the nick of time to run to a bathroom).

Men reading this (Are there any? How I’d love that!) may appreciate this comparison: my aging husband, 40 years later, suffered mood swings and had to wear a catheter and incontinence pads during his prostate cancer treatment, and finally understood, firsthand, the physical discomfort and social anxiety women experience every month for five or more days.

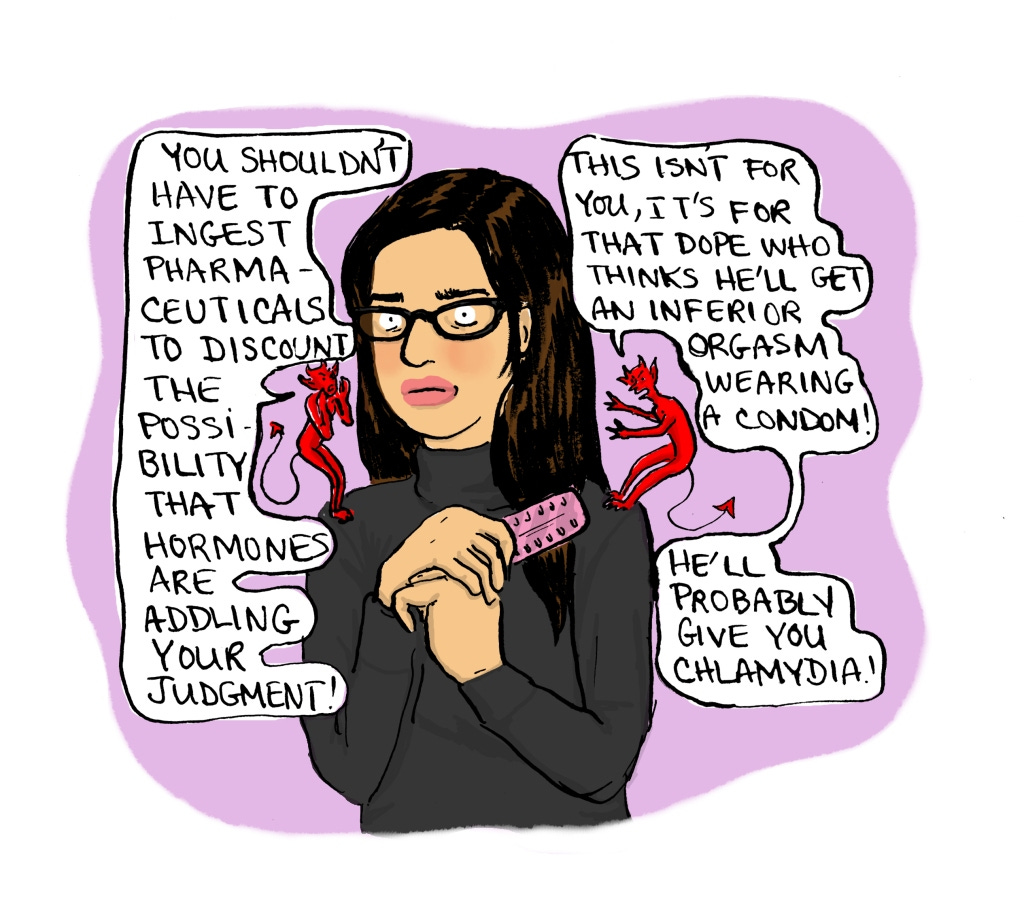

Once I got my first period, I knew that learning to maintain my body expertly would eventually involve taking precautions against unplanned pregnancy. In my 20s, I began regularly purchasing hormones to ingest for that purpose in the form of The Pill. I’d been dying to take The Pill ever since I’d heard that it might mitigate my copious periods and make them a little less painful.

Regulating my hormonal balance with The Pill also meant my pre-menstrual “moodiness” was also officially reined in. I would now be able to tell the difference between true indignation over real injustices, and irrational emotional outbursts due to that old bogeyman, PMS. It was marvelous to me that taking a pill could mean men wouldn’t be able to “gaslight” me into thinking I was misperceiving things due to hormonal imbalance anymore — though they would never stop trying.

In fact, I soon realized that menstrual pain made the crap a woman has to put up with on a daily basis much less tolerable, and that my impatience wasn’t a sign of mental unbalance at all. It simply made me more pragmatic about what I’d deploy my energies upon. Instead of being treated to my usual feminine forbearance, someone irritating me with incompetence at work or stupid excuses at home would be summarily dispatched, as they well deserved to be. Acting/being perceived as if I was “on the rag” often meant I was just being more efficient in ways people didn’t expect or appreciate from a woman.

There seemed to be so many reasons to take The Pill and they all involved keeping things, including myself, under control. The truth is that The Pill, for a good 15 years of my life, became more of a linchpin in my ability to function physically in the workplace, than a form of birth control. I felt dependent on it to keep my skin clear from “monthly outbreaks” — note the language: even a pimple is a prison riot in the jail cells of idealized femininity! — and to keep my bodily functions from humiliating and debilitating me. I was afraid that without it my friends and coworkers and boyfriends over the years would think I was an irrationally emotional, annoying bitch, and that my life would fall apart if I ever stopped taking it.

I was not the only one. Whether a woman should ever be pressured to second-guess and denigrate her mind and body to the point of self-medicating with hormones or not, this is how I draw a direct line from my menstrual cramps to a woman’s right to have access to birth control — birth control isn’t the only thing the Pill is used for. I’ve since decided many of the off-label uses of the Pill are the result of “Big Pharma’s” willful lack of interest in understanding how a woman’s body really works.

In my later 20’s my body encountered the inevitable STD’s a woman’s body risks and often contracts when depending on the Pill and not using condoms. I contracted (and treated, and cured) a goodly amount of cooties over those years. I say this freely and without shame, because, guess what? That’s life, and you damned well know it if you’re an adult who has had sex more than a few times, and it’s about time the shame was removed from the discussion.

I have probably spread a few of those cooties, too: my tepid apologies, fellas (apologies duly extended to your sexual partners during and/or after me, as the case may be, if they were just as stupid as I was and forewent condom use). Like many before and after me, I was ignorant, desperate to be cool and be liked, and I’ve subsequently learned to act more responsibly toward myself and others.Since I was a “serial monogamist” and only had sex with my boyfriends, all of whom denied being carriers of the various cooties I caught, it’s quite a “mystery” where the cooties came from, but I’ll tell you what: I know I wasn’t born with them. I was a good sport about it, polite enough to pay for one boyfriend’s very expensive antibiotics before dumping him and swearing off men forever (or more like a year, it turned out) when he refused to believe he had given me chlamydia (again) and not the other way around. Once, I was also sporting enough to decline sex with a friend who didn’t want to use a condom, thinking if I claimed I hadn’t been tested for STDs in a while he might come to his senses. He said, “Don’t worry, people like us don’t get AIDS.” I pretended I was more worried about him catching something from me rather than be truthful and say I’d never risk having sex with someone as ignorant and prejudiced as he had just confirmed himself to be. He was just the kind of Nice Clean Man I learned to be afraid of.

The lengths I’ve gone to, to avoid hurting a man’s feelings.

By my 30’s I had to learn to use condoms because, as a common long-term side-effect no one had told me about when I began taking The Pill, it was making my vaginal membrane too thin, making sex painful and destructive. My gynecologist declared that she had observed, “Micro pill equals micro membrane!” She advised me to cease taking The Pill since I wasn’t sexually active at the time, and gave me a prescription for the “morning after pill” to keep at home, “just in case.”

I spent a year or so re-balancing my hormones, ingesting many different herbs and supplements like dong quai and evening primrose oil including some I would later read about in my medieval studies (chasteberry, red clover, sage), tinctures (yellow dock, Shepherd’s Purse), all in the interest of re-equilibrium. It was during this time that I discovered “Ovarian Kung Fu” in a book by Mantak Chia and began using a crystal egg inserted into my vagina to do toning exercises. You may laugh, but my menstrual cramps diminished noticeably, and there’s certainly nothing wrong with a well-toned pelvic floor. I drew the line at lifting weights attached to it.

My break from sex and relationships gave me time to gather myself. I went back to school, began to question my fear of solitude, and learned to sublimate my sexual energy into my love of academic research and writing. While looking for clues to the menstrual practices of medieval nuns for my thesis, I came across a history of menstrual equipment. Intrigued, I read beyond the practices of the Middle Ages and discovered that something called “the menstrual cup,” invented in the early 20th century, still existed in a modern form.

The reason I mention this is because once I began using the menstrual cup, I also began to choose my places of employment and recreation according to whether there were private toilets available in which I could remove, empty and rinse, then replace my cup at my ease. At first I needed a private bathroom with a sink, but later learned to bring a bottle of water into a stall for that purpose. This need reminded me that in developing countries, a woman’s ability to work or go to school at all can be made or broken by her ability (or not) to manage her period in a safe, socially acceptable way.

It also reminded me of a letter Héloïse, the abbess of Paraclete, wrote in the 1100’s to her mentor and ex-lover, Abelard, in which she tells him he’d forgotten to take account of menstruation when deciding what nuns should wear: “For example, the regulations […] about wearing tunics or woolen clothing close to the skin, when the monthly purgation of excess humors makes this something women should avoid?” As far as I can tell, this is the first written complaint by a woman that I could find about a conflict between a woman’s natural, expected bodily functions and the duties of the workplace. The logistics of menstruation (like that other, related, bodily function, lactation) make a woman dependent on infrastructure and the relative benevolence of her family, community, and government.

Another reason the silicon menstrual cup was a life-changer for me was that I no longer felt like I was staunching a wound with sterile dressings to be thrown away like a dirty secret that would end up joining tons and tons of other discarded tampons as solid waste in landfills and oceans. I can say without a doubt that the lifting of this sense of shame and ecological guilt was not negligible to my psyche.

According to the Museum of Menstruation, although she wasn’t the first to come up with a design for one, Leona W. Chalmers the 1930s was the first to patent and successfully market the “catamenial” cup in a form very close to the silicon model I bought for around $30 and used from 1998 to 2018. She is my hero.

The good of my Medieval Studies research was balanced by some bad: in the last year of my studies I had my most unfortunate sexual and contraceptive experience with a fellow medievalist. His penis, it turned out, was abnormally large. “As you see, I am endowed rather aristocratically,” he said, as he clumsily tried to don one of the regular-sized condoms I kept at home. It popped off inside me before we’d finished, giving me an excuse to call the whole thing off and send him home.

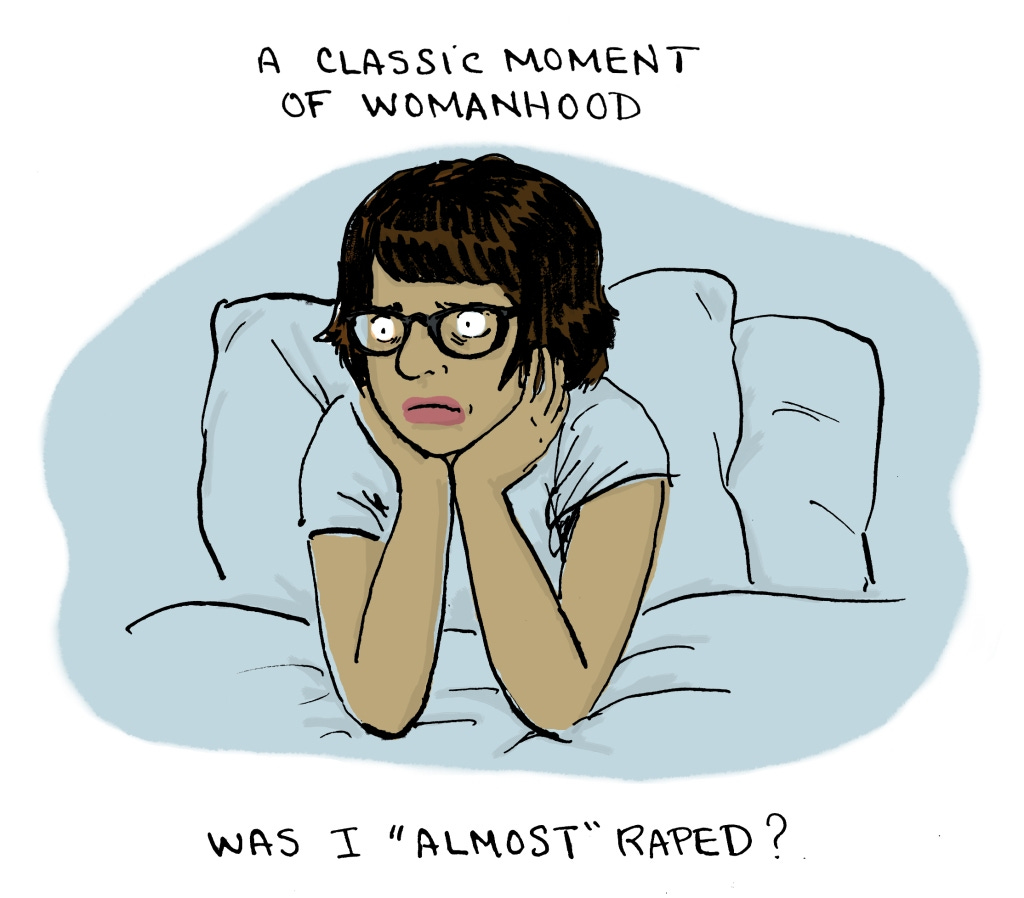

This was a relief because the other problem with this sexual encounter was that it had not felt 100% consensual: it had involved thinking that if I didn’t consent, consent would not be required, and then that would make it rape. The next morning I went to the only pharmacy open on a Sunday with my “morning after” prescription. It turned out this was just a very strong contraceptive pill that would elevate my hormones, then precipitously drop them, inducing a “menstrual flow” that would flush out a fertilized egg if indeed there was one there to flush.

I followed the instructions and blocked all rape-y thoughts of the previous night by concentrating on my feelings of gratitude for having such a responsible gynecologist. I’ll never know if I was pregnant or not, though it’s unlikely. I only knew that it felt as if I’d been given a reprieve after almost ruining my life (and possibly someone else’s). Needless to say, I began to stock different sized condoms in my night-table. Obviously I was responsible not only for my own reproductive organs, but for men’s as well.

By this time I was nearly 40 and well-acquainted with my body. I kept a menstrual diary and even acquired an online/smartphone app for tracking it. I was, however, decidedly devoid of any intention or desire to bear children. My periods were nothing but a useless annoyance to me. I fantasized about finding a way to “vacuum” all my menstrual blood out at once, freeing myself from my heavy, 7-day periods. I searched for and discovered a process called “menstrual extraction.” It was originally conceived of as a way to perform a safe clean-up, post-miscarriage/abortion. But its ability to be used to perform an early, safe abortion sent it underground.

I tried all sort of ways to make my period end faster, including jumping up and down while squeezing my abdomen.

Needless to say, by the late 90s the groups of women dedicated to preserving the practice and knowledge of the procedure had long ago gone underground (metaphorically or for eternity) or retired because of both the stigma and legalization of abortion, which together made these women seem simultaneously dangerous and irrelevant. So, I kept having my periods the old-fashioned way.

When I met my next and last boyfriend, I was pleasantly surprised when he said, before I even had to ask or offer, “The condom is our friend,” as he put one on the first time we had sex. Unfortunately, when our relationship was on the rocks for awhile, I was stupid enough to go back on the Pill and eschew condoms to try to please him, a classic move in girlfriendhood. Boom: I got an STD he had apparently been unaware of carrying.

Once I took care of that, we used condoms for the rest of our sex life because, as I told him, I could forgive him for cheating on me but I wouldn’t forgive him for any more diseases and their expensive and biome-disruptive treatments. For myself, I didn’t need The Pill anymore: I had achieved emotional serenity through my work, and working freelance meant I could usually take the day off when my period was debilitatingly painful or copious. I rejected all allegations of “moodiness” as sexist and annoying.

Sometimes I think back over all the different medications and pharmaceutical products I’ve taken with the aim of whipping my bodily functions into submission for the sake of being able to function without pain and go to my place of employment (Midol and other NSAIDs), not ruin my life (and someone else’s) with an unwanted pregnancy, while also enabling lovers to have condom-free sex, whilst able to consider my judgement rational rather than hormone-addled (a three-fer provided by the Pill), be “clean” (all the antibiotics I took against various STDs)…

I thought about this while looking at advertisements aimed at parents encouraging them to inoculate their daughters (rather than their sons) against HPV. I thought about it when I learned that Viagra (AKA the “Boner Pill”) was graciously covered by my husband’s insurance, while mine didn’t cover anything I could buy to tame my hot flashes. My declining hormones were considered “a normal part of aging,” while impotence in aging males is a national emergency.

Menopause is a well-documented (if not very well-managed or accommodated) phenomenon in a woman’s life, so there are only two things I want to add to the conversation. The first is a sociological and philosophical question that occurred to me during the worst of my hot flash years. I would wonder if the hot flashes, which felt uncannily like the kind of horrible, deeply hot shame I’ve felt during moments of humiliation, were the rising up with a vengeance of all the myriad womanly humiliations I had refused to acknowledge and had suppressed from girlhood to age 47.

Were the two-minute, every-hour-and-a-half-for-two-years hot flashes the price I was now paying for trying too hard against my better judgement to be the “cool girlfriend”? Were a few hundred of my hot flashes penance for that awful night I acquiesced to frightening, overly forceful male desire because I didn’t want to “feel raped”? Were a few hundred others punishment for being too ruthless or fearful (or both) to object to the sexual harassment and sexual discrimination I’d experienced in the workplace? Were some for being too proud to acknowledge their negative effects on my psyche over the years? Were some for being afraid to be equated with “bra burning feminists” in my 20s, for being ungrateful enough to think I was above all that? Or for blithely enabling the slut-shaming of Monica Lewinsky in the 90s?

Who knows? It’s a thought that haunts me.

The second thing I want to tell you about, I don’t really want to tell you about because even someone as shameless as I am found it embarrassing. But, just like that time when I was a pre-teen and my ignorance led me to think I was dying, I really wished someone had prepared me for it. As it was, it took me days of anxiously searching the internet after two months of hiding my embarrassment from my husband to find out that (1) I wasn’t dying after all, and that (2) a woman’s last few menstrual periods can be terribly potent in both color (so concentrated that it will stain your menstrual cup forever) and smell (don’t bother trying to get the stain out of your menstrual cup because the smell will never go away either). It’s natural, it happens, and there are over-the-counter probiotic pills composed specifically for women that resolve this issue. Enough said. You’re welcome.

Well, it has been my pleasure and privilege to be in a position to articulately point out that both the end of my childhood (or the awakening of my reproductive system), and end of my reproductive life (or the return to freedom from it) were heralded by strange new vaginal secretions and smells that mystified me and/or made me wonder if I was dying, sending me searching for answers. Isn’t the search for answers to life and death questions the beginning of every great story, since Gilgamesh? Gilgamesh, meet Eve Ensler.

This is why the story of my body is relevant: reading the signs of our bodies relies on us having other women we can talk to, sharing knowledge from one generation to another. Lacking such unity, there are books or at the very least, the internet. Knowledge and power over our bodies therefore requires and implies the power of literacy and/or the power of women united enough to share their intimate knowledge with each other. The smells and secretions that we’ve been taught to hide and be ashamed of all our lives are actually signifiers of the richness and gravity of living within a woman’s body. The superstitions and denigration around them reveal what a patriarchy most fears and attempts to suppress: our power through and over our own bodies.

This illustrated essay was originally published on Longreads as part of Carolita Johnson’s six-part series, A Woman’s Work.

Carolita Johnson is a writer, storyteller and cartoonist who contributes regularly to the New Yorker.

The number of secret (and often horrifying) things that happen to a woman's body during menopause, but that no one tells you about, are too numerous to count. I can't help but think it's not coincidental that women have to go digging through the internet to figure out what the hell is happening to our bodies during menopause.

The personal narrative you shared about the journey of your body, particularly in relation to menstrual health and societal perceptions, is both compelling and deeply relatable. Your exploration of the menstrual experiences from medieval times to the present highlights a universal struggle many women face in understanding and embracing their bodies amidst societal norms and pressures. The historical anecdotes and your personal experiences weave together a story that many women can identify with, shedding light on the complexities and often misunderstood aspects of menstrual health.

Your journey underscores the importance of open conversation and education about women's health. It's striking how misconceptions and societal attitudes have influenced women's relationships with their own bodies, often leading to fear and misinformation. The evolution of menstrual products and the various methods women have used to manage their periods reflect a broader narrative of women's empowerment and the ongoing fight for bodily autonomy. I, for example, have frequent menstrual pains and have felt relief from using natural product remedies (op https://www.naturalmedicineheals.com/calm-cycle). It's life-changing because the pain on "those days" drains all of a woman's energy.

Your reflections serve as a reminder that understanding our bodies is a continuous journey, one that requires compassion, education, and a supportive community. The way you've connected your personal experiences with historical perspectives offers a powerful testament to the resilience and adaptability of women in the face of evolving societal norms and medical understanding. Your story is a valuable contribution to the ongoing conversation about women's health, emphasizing the need for more open dialogues and a deeper understanding of the female body across different stages of life.