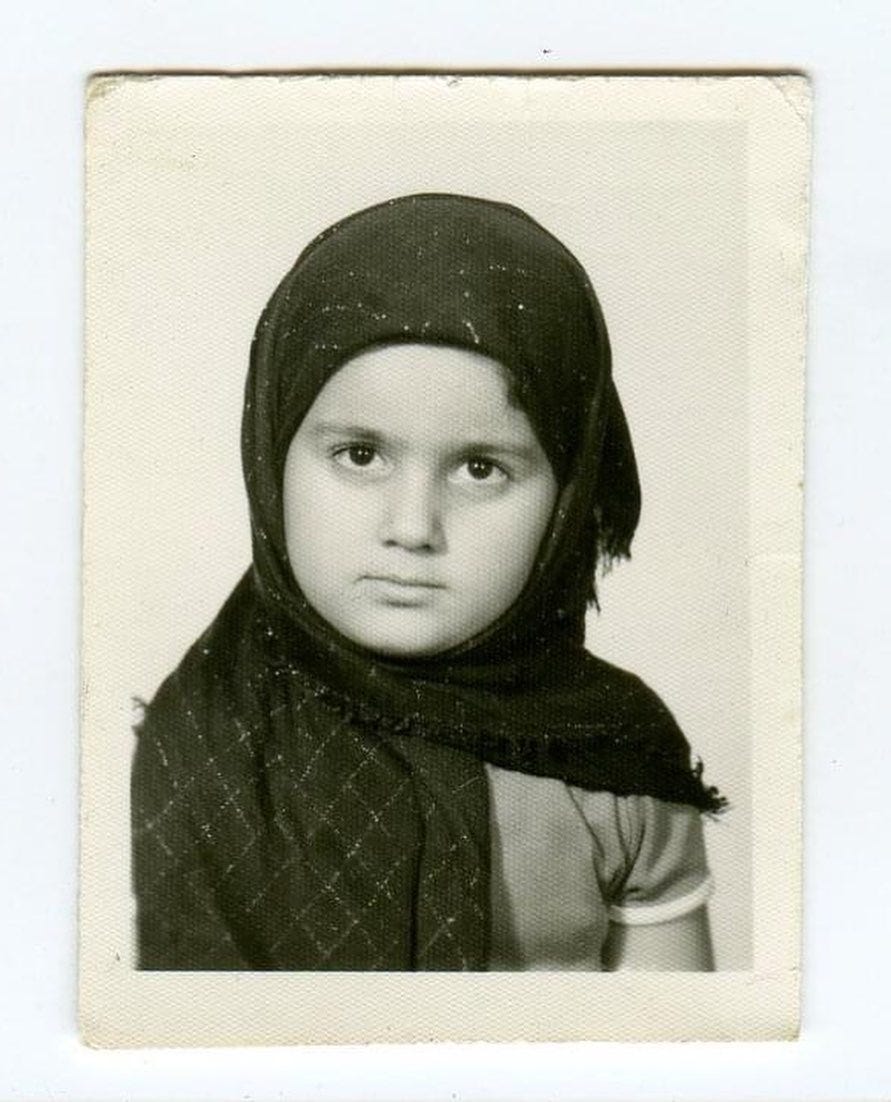

Scattered Pictures #2: Naz Riahi As a Young Girl in Post-Revolution Iran

"The biggest women's rights movement in the world is happening right now in Iran. It would be a mistake for us to turn our backs on that."

This is a new series called “Scattered Pictures” in which contributors share an old photo and its backstory. - Sari Botton

Naz Riahi (she/her) is an Iranian writer and director. Her work explores the spaces, emotions and opportunities of otherness and isolation, informed by her experiences as an immigrant. She was named a Filmmaker Magazine 25 New Faces of Independent Film and is the recipient of a Vimeo Staff Pick, Vimeo Best of the Year Award and NoBudge Film of the Year. Her films have garnered praise from BAM, The New York Times and Fast Company among others. Her creative writing has been published in Oldster, Pipe Wrench, Food & Wine, Los Angeles Review of Books, Longreads, Catapult, The Fader, Doré, Guernica and more. She created the dialogical art project, Bitten. In recognition of Bitten, Naz was invited to the Obama White House. An essay she wrote about the experience received public praise from President Obama. She is the recipient of a NYFA City Artist Corps Grant and holds an MFA from the New School.

When our second grade teacher told us, her classroom of 8-year-old girls, to take off our roosary (headscarf), we were confused. We looked around the room at each other, frightened, unsure of what to do. Was this a trap? Was she going to report us? Have us arrested? Have our families killed?

It may seem dramatic to ascribe so much power to a teacher (she was also our vice principal), but she was affiliated with the Islamic regime, and no evil was beyond them.

In the early 1980s, just a few years after The Revolution and takeover of the brutal Islamic Regime, girls, age 6 and older, were subject to compulsory hijab laws. Meaning we had to wear hijab in public.

Sometimes, we could push it by a few years if we looked young enough, but it was always required in school, even though our schools were segregated by gender, no matter our age. Hijab laws at the time also indicated that we had to wear a loose fitting robe, what we called a manteau, covering our clothes and obscuring our figures. We couldn't show our skin, wear nail polish or makeup, or have any hair exposed through our headscarves, which we wrapped tightly around our faces.

In the early 1980s, just a few years after The Revolution and takeover of the brutal Islamic Regime, girls, age 6 and older, were subject to compulsory hijab laws.

To put us at ease, our teacher said, "I'll go first."

She unwrapped her chador, a heavy mass of black fabric shrouded around her, and took it off. Beneath it, we saw that she was skinny and tall, but her hair was still covered by her roosary and her clothes obscured by a long loose-fitting coat.

"It's just us girls," she said, kindly. "So it's fine."

One by one, nervously, we took off our headscarves.

I held my breath, as I peeled the gray roosary away from my face and off, afraid still, of getting into trouble. But also, feeling a flicker of hope flash through me. Was she going to allow us to be free? Even if just for the duration of her class?

We looked around the room, seeing each other's hair for the first time. Little smiles washed over our faces.

Hijab laws at the time also indicated that we had to wear a loose fitting robe covering our clothes and obscuring our figures. We couldn't show our skin, wear nail polish or makeup, or have any hair exposed through our headscarves, which we wrapped tightly around our faces.

"See," she said. "Isn't that nice?

She waited for that sentiment to sink in.

"Now, I want you to take a single strand of your hair and pull it. Not hard enough that it breaks off, but hard enough that you feel it."

We did as she asked.

"Does that hurt?"

"Yes."

"Okay,” she said. "Now take another strand and do the same thing."

We did.

"It doesn't feel good, does it?"

"No."

"I had you do this exercise so that you would understand that if a man who is not your husband, sees even a single strand of your hair, you will hang by that strand, for eternity, over the fires of hell, feeling that relentless pain without relief."

After that, she asked us to put our roosarys back on, cover ourselves in fabric, hide our hair and our head.

At the time, my Baba was a political prisoner in Iran's notorious Evin prison and we were spending our days at different government buildings in Tehran, trying to save his life. It didn't work. A few months later, he was executed and a few months after that, my mother and I escaped to the U.S.

I didn't stay in that class or that school long. Soon after this incident my mother pulled me out of school entirely. At the time, my Baba was a political prisoner in Iran's notorious Evin prison and we were spending our days at different government buildings in Tehran, trying to save his life. It didn't work. A few months later, he was executed and a few months after that, my mother and I escaped to the U.S.

That day in second grade and so many others like it have haunted me for years. Growing up a girl in post-revolution Iran is a traumatic experience. Living as a woman under the Islamic Republic is a traumatic experience. It is generational and frightening. I understood my own mortality and the threat of death that permeated the world around me by the age of 5. I understood, too, the unfair rules I was subject to, because of my gender.

A month ago, I posted to Instagram a photo of myself as a child in hijab, along with this story. This was in response to the brutal killing of Mahsa Jina Amini, a young Kurdish woman who was arrested for improper hijab and then beaten to death, while visiting family in Tehran. It led to an uprising in Iran, which has since grown into a revolution to overthrow the Islamic Republic.

After I posted the photo, I invited others to share their #hijabnightmare. I heard from women all over the world who experienced many kinds of abuse over compulsory hijab laws. One thing that surprised me the most was that what happened to me in second grade wasn't unique. The threat of burning for eternity over the fires of hell while hanging by single strands of hair was actually a lesson in the school curriculum for all girls across Iran.

It is in sharing our stories that we find we are not alone, that we are not crazy and that a mass of us, together, can make impactful change.

I implore you, readers, to continue supporting the Iranian women and girls (some as young as 10) and their supporters, who are risking their lives to fight for freedom. Keep paying attention to what's happening in Iran and amplifying the voices of protesters by sharing on social media.

I invite anyone reading this piece who has had to live under compulsory hijab laws (in Iran or elsewhere) to share their own #hijabnightmare using that hashtag on social media (feel free to tag me and I'll share your story, too).

I also implore you, readers, to continue supporting the Iranian women and girls (some as young as 10) and their supporters, who are risking their lives to fight for freedom. Keep paying attention to what's happening in Iran and amplifying the voices of protesters by sharing on social media. Be our voice and demand that mainstream news cover the story and that Meta stops shadow-banning protestors’ stories.

The biggest women's rights movement in the world is happening right now in Iran. It would be a mistake for us to turn our backs on that. Especially now when so much of the world is at peril. Regardless of where we live, the bodies of women, queer people and people of color are always the battleground for fascists regimes.

To find out more about what's going on in Iran, you can start with a few Instagram accounts: @from__Iran has been doing great work and sharing vital news, @iamnazaninnour and @centerforhumanrights are two more with English language content And, you can find me and share your #hijabnightmare at @nazriahi.

Thank you for this. My father came to America before the revolution and never went back. The remainder of my Iranian family has lived in the diaspora/ exile since the revolution. I am grateful I wasn’t born there and heartbroken that the country my father loved doesn’t exist and instead continues to brutalize and murder innocent people. Thank you for sharing your story, spreading awareness, and using your gift of expression to so eloquently detail the experience of this type of oppression. 💚💚💚

Thank you for telling your story.