On Longevity, and the Stubborn Gene

Julie Metz witnesses the defiant aging of her father and his second wife and contemplates how her own relationship to risky hiking has changed.

A hospital intake nurse brings up my dad’s records on her screen, noting his date of birth, 1925. Then she scrutinizes me, as if I were the patient.

“You’re his daughter?”

I nod.

“You’ve got a long way to go,” she remarks, before turning back to her computer.

That’s if I’ve got the longevity gene.

“We’ll see.” I reply.

A hospital intake nurse brings up my dad’s records on her screen, noting his date of birth, 1925. “You’re his daughter? You’ve got a long way to go.” That’s if I’ve got the longevity gene.

A nurse enters with a wheelchair to take my dad to the operating theater where he will have a hernia repaired. Unlike the surgery he had over fifty years ago, this one will involve hi-tech mesh, and since the procedure will only take about an hour, I can bring him back home today.

Later, in the recovery area, my dad smiles at me, groggy from anesthesia, but surprisingly cheerful. “I guess I have to live to 100 now.”

“To get your money’s worth, right?”

My dad has always been thrifty, like many who grew up during the Depression. His parents lost houses and cars, and food was often scarce. Once he found a quarter on the sidewalk—real money in 1935. He gave the coin to his mother who bought a bag of fresh peaches. When he told me the story, I could tell that so many decades later—years filled with plenty of elegant meals at Michelin-star restaurants—he could still taste that juicy fruit.

My dad endures the post-op discomfort with admirable stoicism, another trait of his generation. Three more years without unpredictable spasms of acute abdominal pain, and an uncomfortable truss belt—totally worth it. Who knows? He might make it past 100. As his caregiver likes to say, “Your dad is one of one.”

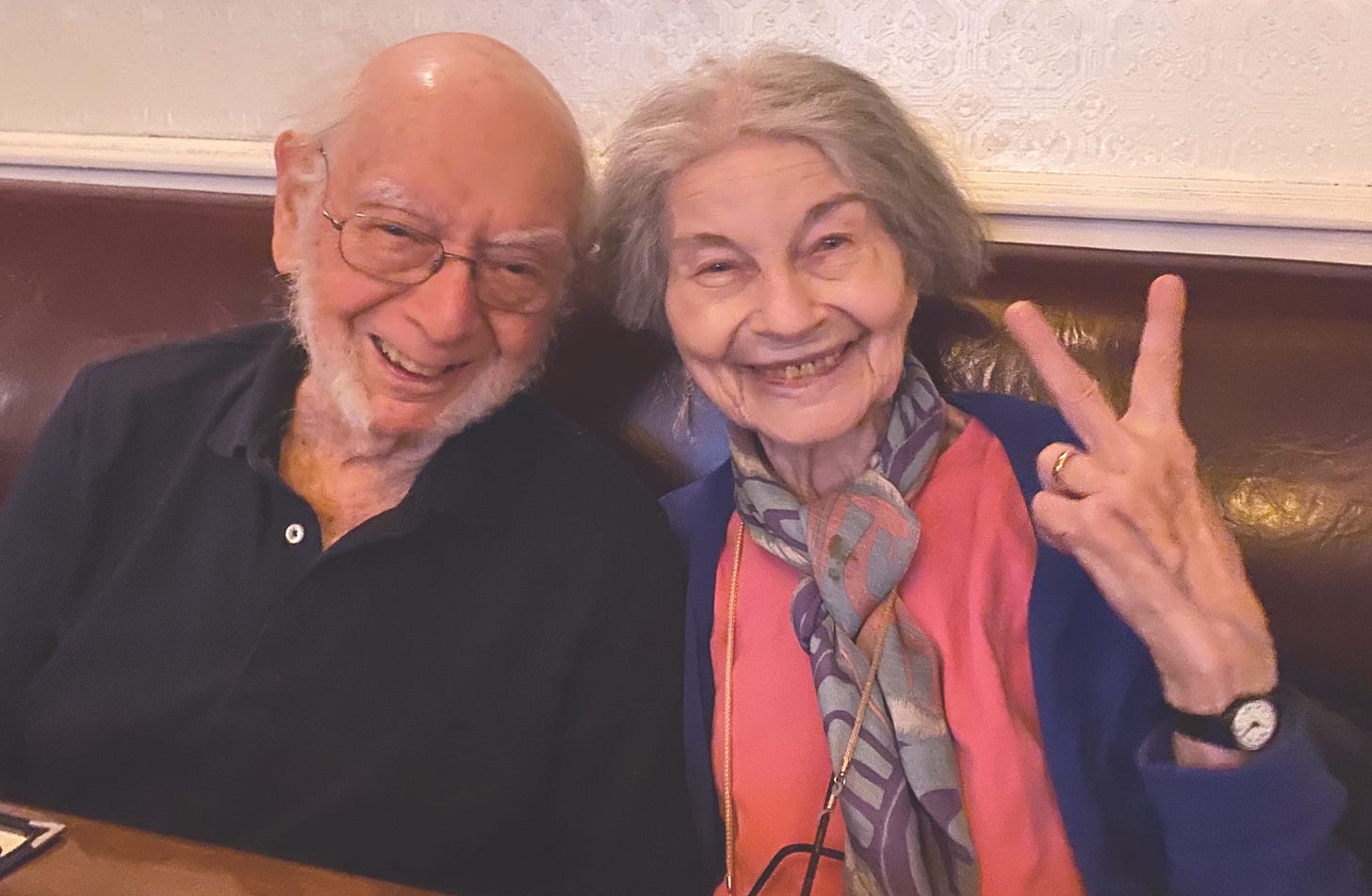

By March of 2023, my dad had healed from his surgery and V had recovered enough from her fall the previous December that she could walk up and down the hallway in their apartment. Her stubborn refusal to consent to a fulltime walker or a cane seems to be working for her. My dad also walks without assistance.

My dad met his second wife V on his second successful blind date. The first one was in 1947, when he met my mother. My mother was a tough woman but she did not have the longevity gene. My dad, widowed after fifty-four years of marriage, wasn’t ready to give up on life and he didn’t want to live alone. A woman in his Upper West Side apartment building knew a widow who’d lost her husband to cancer.

Once this matchmaking effort was underway, my dad told me he’d arranged a first meet-up at the Metropolitan Museum, for a Saturday, the very same afternoon that I’d made plans to join friends there with our kids. My dad and I scrambled our arrival times to avoid an awkward encounter in the museum lobby. How funny, I thought, a few decades earlier and that would have been me trying to dodge my parents. Soon enough, I acquired a stepmother, fortunately not of the Snow White variety.

By March of 2023, my dad had healed from his surgery and V had recovered enough from her fall the previous December that she could walk up and down the hallway in their apartment. Her stubborn refusal to consent to a fulltime walker or a cane seems to be working for her. My dad also walks without assistance.

“Don’t grow old!” V advises me on the regular, as if I have any control over the matter. In spite of her complaints, it seems to me that extreme old age is working out well enough for them, better than the alternative. “Your dad and me, we are the survivors.”

A few generations ago our stubborn peasant ancestors were harvesting potatoes in Galicia and Ukraine. I definitely inherited the stubborn gene.

There’s a fine line between stubborn and stupid. When I was a teenager I spent many summers in Maine climbing up and down rocky trails in worn-out sneakers or flip flops, or even barefoot. One afternoon, I made my way down a cliff to inspect a tidal pool at the rocky sea edge. What a miracle of a metropolis this one was—teeming with multicolored seaweed and crabs and baby lobsters and periwinkles and teensy barnacles that swept water into their orifices with frond-like appendages. The sun was warm; I lay down on a smooth patch of granite and dozed for a time, awakening as freezing water lapped at my toes. The tide was rising. The place where I was resting would soon be submerged. And the route back up the rockface was life-threatening.

Narrow ledge by narrow ledge, handgrip by handgrip I made my way up. I couldn’t look down. Gulls swooped and yelled at me. “Okay, okay,” I yelled back. “Just let me get to the top and I’ll be out of your way!” A few feet from the summit, within sight of the grassy meadow and the woodland path that would return me to a warm meal and a bed to rest in, I stood on a foothold, exhausted.

When I was a teenager I spent many summers in Maine climbing up and down rocky trails in worn-out sneakers or flip flops, or even barefoot…When my partner and I go hiking we now use adjustable walking poles. I used to shun such aids as they seemed to mark me as an oldster. Now I’m grateful that these poles give us some of the advantages of four-legged animals.

The best hand grip was a reach for a petite person like myself. This would have to be an all-or-nothing grasp, full commitment, no room for error. The sun had dropped during the time it had taken me to make it this far. An hour? More? I shivered. The gulls circled. When I finally made my move, I scraped my bare leg on a crag as I pulled myself into the safety of the meadow. Relief and pain comingled as I flopped onto my back panting, blood staining the blades of grass. I felt like an idiot but I’d survived.

When my partner and I go hiking we now use adjustable walking poles. I used to shun such aids as they seemed to mark me as an oldster. Now I’m grateful that these poles give us some of the advantages of four-legged animals.

If we walk quietly, and we’re lucky, we might surprise a doe and her fawns along the trail. They move across uneven terrain without effort, adjusting their weight on slender legs. As they leap away from us in high arcs, they seem to be flying in slow motion. I rest for a moment, leaning on my walking poles, admiring their grace. In a flash, the deer become one with the forest, and we make our way, with care, down the mountain.

Thanks, Julie, for a great essay. One week ago just at this time Monday morning, I put a thermometer in my father's mouth and got a reading of 99.5. I was glad because all weekend I thought he was declining for good, as he is 97. Then I gave him the Covid test, and he tested positive. After a virtual appointment with urgent care -- I sat him in front of my computer -- he went to bed. That evening he fell over his walker (he tends to grab it by one handle first) and kept calling me and my brother, but we could not hear him on the other side of a big house, so he crawled and going to check on him, my brother found him on the floor. Together we could not lift him, so I called 911 and the paramedics came. He was disoriented and had 101 fever but eventually was up and walking with his walker because he didn't want to go the hospital. I slept (mostly not slept) on the floor of his room the next three nights and kept feeding him Tylenol. (He would not take the prescribed Paxlovid, saying the side effects would make him worse than he fell -- um, felt.) Upshot: he had a very mild case and has been symptom-free and tested negative yesterday. Meanwhile, my brother, only 69, has been much sicker with Covid. I have mild cold symptoms but so far have tested negative.

I don't think there's a longevity gene, but my father's father and sister lived to 90, and he had lots of uncles and aunts on both sides of his family who lived to 96 or 98 or in the case of his Uncle Joe, lived to 104 and was amazing until just before he died. (On my mother's side, two of her aunts -- one of them, a Metz by marriage -- lived to 97 and 98.)

(Right now I can hear my father in his walker walking past my room to the garage so he can see if the New York Times and Arizona Republic have been delivered. Soon he will be raging against Donald Trump.)

Julie, I'm glad your father and stepmother are the way they are. Good luck to you and to all of us Metz fans.

Julie, ahhhh...the walking poles. All we need to do is make them decorative/chic and suddenly, they will be trendy and "on point." ha/ha I had a 19-year-old tell me my outfit (I'm 62) was "on point." She looked pleased, so I knew that was a compliment. Funny, I just pulled a few things from my closet I had forgotten about for some time. "Yes" to changing/evolving and living!