My Mother Wanted Me to Be Happy.

To her that meant being thin, married, and a mom.

My mother’s fondest wish for me when I was growing up was that I would one day be thin enough to land a man. It didn’t work out for her. She died last year at age 79, survived by two happily married daughters, one happily married son, seven grandchildren, and one childless, unmarried daughter who is currently unable to buy jeans in normal stores.

She herself predicted this exact outcome circa 1979. “Boys will never like you if you look this way,” she told me when I was 11, right around the same time the sixth-grade social dance of Who Likes Who was starting to be a thing. It was the explanation for why she needed to pick me up Wednesday after school and take me to see a nutritionist. Most likely the nutritionist was recommended by my pediatrician, as I can’t see my mother having the wherewithal in 1979 to figure out a) what a nutritionist was and b) where to find one in Northwest Indiana. Honestly, I don’t remember this stark assessment of my future coming as any huge surprise. My lazy eye had recently been fixed via surgery, and given the first three letters of my last name, it’s not like I was having the world’s greatest time in elementary school.

“Boys will never like you if you look this way,” my mother told me when I was 11, right around the same time the sixth-grade social dance of Who Likes Who was starting to be a thing. It was the explanation for why she needed to pick me up Wednesday after school and take me to see a nutritionist.

In TV writing, we call this a hat-on-a-hat. Essentially, it’s when two details serve the exact same dramatic purpose. In my most beloved childhood photo, neither of these hats is yet apparent: I’m a typically sized toddler whose most defining characteristic is an oversized halo of Barbra-Streisand-in-A-Star-Is-Born curls. But I have no memory of that person. The curls were gone by the time I got to kindergarten, presumably because they were impossible to manage—although my older sister’s longer, straighter Marcia Brady hair also got the chop around the same time. Hair and weight. On the Hidden Brain podcast, I once heard linguist Deborah Tannen single out these issues, along with clothes, as the big three “flash points” most mothers and daughters have conflict over. “From the point of view of the mother, this is caring… but any time you make a suggestion for improvement, you are implying criticism. And that’s what the daughters hear.”

Are you married? Do you have children? Have you stayed thin? When I was growing up, these were the ruthless standards by which the women of my mother’s generation constantly seemed to be judging themselves and—when it was safe to gossip—each other. My recollection is that you only needed two out of three for a passing grade. Married and thin but no children? Sad but understandable. Married with children but had not “kept your figure”? We’ll allow that. Had children and your figure, but no man in evidence? We’ll make a sitcom about that and call it One Day at a Time.

My mother herself wasn’t thin.

This sometimes surprises people who don’t understand how weight works (it’s genetic) –or how parents work. She had four children, and my father stayed devotedly by her side for more than four decades until he passed away suddenly in 2010, but she never got anywhere near close to attaining that third marker of mid-century female success. Even in her wedding pictures she has the sort of incredibly full, round face that makes a person seem “fat”—no matter what size the rest of their body is. At my most thin in the early 90s, I was able to fit into a couple of her incredibly forgiving A-line dresses from the mid 60s, and since my “most thin” is a size 14, I think it’s safe to assume that hers was probably in the same ballpark. In addition to those weekly trips to the nutritionist, which I don’t remember lasting that long—maybe a year, tops—I also have a vague childhood memory of going with her to at least one Weight Watchers meeting. Throughout the 70s and 80s, I’m sure she must have made other Betty Draper-esque attempts to “reduce,” but none of them worked very well. Still, if you were female, you were expected to try.

Thus, the nutritionist.

Hair and weight. On the Hidden Brain podcast, I once heard linguist Deborah Tannen single out these issues, along with clothes, as the big three “flash points” most mothers and daughters have conflict over.

The main thing I remember learning in her office was the correct serving size for ice milk, a watery ice cream substitute (half-cup), so most likely all she was teaching me in those afterschool sessions was what we would now call “portion control.” Starches—whatever those were—were still widely believed to be the problem. Low-fat wasn’t even a glimmer in anyone’s eye. Because I had an older sister, I could tell this scheme was a last-ditch attempt to make me presentable before junior high, when everyone got their periods and started wearing skintight Jordache jeans. There may have been some mention of “health,” but that linguistic sleight of hand for talking about weight hadn’t been perfected yet. Nor was there a constant stream of cultural chatter about how trying to look more sexually alluring was something women did primarily for themselves, to buoy their spirits. Dieting to stay thin? Wearing makeup and high heels? Straightening, curling, and/or—lest we forget—feathering your hair? When I was a kid, it was still pretty widely acknowledged that women did these things to please men, to earn their favor, to get along a little better in a world that was explicitly designed to work against them unless they looked a certain way. That’s the secret the moms of that generation knew. The 1960s brides who put plastic on the couch and didn’t necessarily go to college. They knew being thin mattered … and they didn’t pretend otherwise.

It worked, too—whatever reasonably sensible weight loss plan my mother and the nutritionist agreed to put me on. As I headed into seventh grade, I distinctly remember receiving at least a few compliments on my ever-so-slightly changed appearance, but here’s the catch. It didn’t work so well that I developed a zeal for dieting. Or for vaguely insulting compliments. I can remember desperately wanting to be thin, to be normal, to fit in—but whatever mental toughness was required to make that dream a reality, I simply did not have. “And so, at 12, I summoned my willpower and started jogging,” wrote Sam Anderson in an essay that ran earlier this year in The New York Times Magazine about how being an overweight kid who slimmed down before high school had shaped his entire identity.

Reader, I did not start jogging.

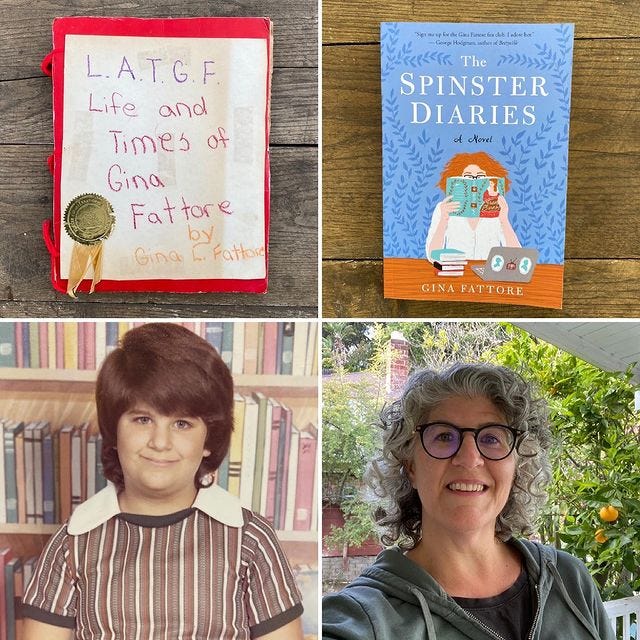

Instead, I made contingency plans—crazy dreams I could still pursue even if I never did make it to the promised land where regular-sized girls exhausted themselves fretting over those last ten pounds. At 15 I had already attended two young authors’ conferences, edited my junior-high newspaper, and published a short, observational essay in the Chicago Tribune. Writing, I knew, was something a person could excel at despite being overweight. (To this day, I’m extremely grateful that during my formative years I never stumbled upon that picture of Joan Didion leaning against the Corvette.) Even though I had never actually met one in real life, becoming a writer—specifically a spinster writer—gradually crystallized in my mind as the solution to all of my problems: it became my fondest wish for myself. To achieve it, I didn’t have to be thin and pretty. All I had to do was write.

Are you married? Do you have children? Have you stayed thin? When I was growing up, these were the ruthless standards by which the women of my mother’s generation constantly seemed to be judging themselves and—when it was safe to gossip—each other.

Oddly, the one possibility I never considered was that my mom was wrong about how my size would invariably hold me back when it came to boys, dating, and the social dance of Who Likes Who. By the time I was in sixth grade, I had already been teased enough that I believed her without question. Eventually, the visits to the nutritionist stopped. I can’t remember exactly why, but her office was in a neighboring town, and driving your children all over creation hadn’t yet been established as a love language. Over time I settled into being the sort of chubby high school girl who is everybody’s friend and does freakishly well at school. My dad never once commented on my weight when I was growing up, but he was the kind of dad who routinely wondered aloud why a B plus couldn’t just be an A minus. I never crossed over to the other side and became the sort of “normal” 1950s-style teenage girl my mom must have been envisioning when she decided to intervene in my weight problem. I never had a boyfriend. I didn’t go to the prom or high school dances. I had to buy all my clothes at Lane Bryant.

Spoiler alert: when I went away to college, I lost weight. Sadly, the diet plan that worked for me is impossible to monetize. I do not like pizza, and for the first time in my life I was half a continent away from my mother. By the time I graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Columbia with a degree in English, I had become the person both she and I had so desperately wanted me to be when I was a teenager: I had become a size 14. In my 20s, I made some cursory attempts to figure out the social dance of Who Likes Who, but even as a thinner person, I lacked the confidence to pull them off, and by the time I reached my 30s, the hard-and-fast rules of my mother’s generation had simply vanished, along with pantyhose and half-slips. No one was saying out loud any more that romantic love was something straight women earned by being thin and pretty. Now the conventional wisdom was that it was either a) a numbers game or b) something you earned by fixing your insides—i.e., “working on yourself,” overcoming your fear of commitment, lowering your ridiculously high standards, etc., etc. Theoretically, this was a change for the better, a game anyone could win. But I never fully committed to the numbers game—all the extra energy and ambition I had in my 30s and 40s I poured into realizing my childhood dream of being a writer, working on multiple television shows and writing a book—and in the end Adult Me proved to be just as incompetent at self-actualizing and lowering my standards as Teenage Me had been at losing weight.

Over the many decades that I failed to produce son-in-law #3, my mom periodically checked in with my sisters to see if I was gay, dropped constant references to “how good it was to be married,” and continually alluded to the possibility that I might “meet someone”—but she never really mentioned my weight again, not even during the times when I fell out of straight sizes. She was clearly disappointed that I never pursued the identity she most wanted for me—wife and mother—but eventually she did come to accept the one I chose for myself. In the last few weeks before she died, from complications of dementia, there was very little she could say or remember. She remembered that I was a writer.

These comments are everything! Feeling understood is like a drug. Thank you all so much for taking the time to read and sharing your own experiences. What an amazing community!

This is heartbreaking and true. I’m 65 and the expectations from our childhood and teens have been so ingrained that even now everything you wrote resonates. Mom was fat and dad was thin and he never let her forget her “failure” to “maintain” a thin figure--this despite 10 pregnancies and 7 children. I got my tubes tied at 20. I am thin with little effort, yet I still compare myself to younger women whose bodies are firm and fresh. We live surrounded by examples of why we will never be good enough.