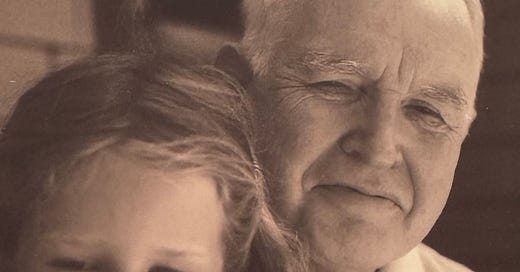

My Father, Myself

Cameron Walker reflects on what she learned being raised by a much older—yet still tireless—dad.

I don’t remember what the old woman looked like, only what my dad said when he saw her. We were driving in Berkeley, turning onto Fulton from Durant. It was afternoon, sunny. My dad slowed for a moment, and I thought he was going to give me more advice about driving a stick shift, which he was trying to teach me. The clutch, and then the gas. It’s the interplay between the two.

Instead, he looked out of his side window at the woman who was making her way slowly along the sidewalk. “Someday,” he said, “that will be you.”

Sometimes I remember that the woman wore a black, tasseled shawl around her hunched shoulders. Other times I think she inched along with a walker. There are times she has a headful of curly white hair and a tiny frame, but walks unbowed. When I try to recall her face, there is nothing there, just the blur of features that might linger from a fading dream.

In grocery store lines, cashiers referred to him as my grandpa. Sometimes kids at school did, too. When I was 10, the son of a family friend—a few years younger than I was—told me solemnly that my dad was going to die soon. When my parents married, he was 51. I was born two years later, my brother three years after that.

My dad, looking through his window at this woman, was in his late 60s, fully gray and partly balding. The reading glasses he wore were probably stashed in one of his pockets. He squinted into the sun, the distance glasses he was supposed to wear while driving nowhere to be seen. When he used his hands to demonstrate how my feet should work on the pedals—left hand tilting back to let out the clutch, right fingertips dipping downward to gently accelerate—the backs of them were covered with brown spots and wrinkles, and more often each year, purpling bruises on the thin skin.

I can’t remember if I said anything. I was a teenager: I probably grunted. I was annoyed by what I imagined to be his attempt at philosophizing. Was he trying to tell me that life was short? Did he think I didn’t notice age? Because I’d been noticing his for what seemed like all my life.

So had other people. In grocery store lines, cashiers referred to him as my grandpa. Sometimes kids at school did, too. When I was 10, the son of a family friend—a few years younger than I was—told me solemnly that my dad was going to die soon.

When my parents married, he was 51. I was born two years later, my brother three years after that. As I grew older, most of what I noticed were the differences. He didn’t play sports like the other dads, couldn’t talk to them about football, had no desire to go out with them for a beer (he’d lost his taste for it during World War II). Around my friends’ dads he seemed too quiet, too intellectual, too awkward—things that I worried I was, too.

Worse than feeling different was feeling scared. I didn’t need another kid to point out that my dad’s time was limited. I watched him constantly and felt the swooping buzz of panic when he cut himself, or fell down, or caught a cold.

As I grew older, most of what I noticed were the differences. He didn’t play sports like the other dads, couldn’t talk to them about football, had no desire to go out with them for a beer (he’d lost his taste for it during World War II). Around my friends’ dads he seemed too quiet, too intellectual, too awkward—things that I worried I was, too.

Of course, it wasn’t all terror: All parents die someday, but having that knowledge early on made our time together sweet. He ended up retiring while I was in high school, so he was around to drive me to practice, do the laundry, play board games as a way of distracting me from high school drama. We shared a love of reading and writing that brought us even closer together when he asked me to edit his novel: a reflection of what he’d seen and done over his long and varied life. When he died, at 78, when I was 24, I fell apart, a little—but it didn’t feel like a tragedy, only the grief of having loved someone who was gone.

It would be nearly ten years before I’d start having my own children—time enough to make his absence familiar. It was almost a source of confidence: the thing I’d most dreaded had happened, and I’d made it through. I thought that as a new parent I would notice only my father’s absence, but instead I felt his presence again—and a new admiration that he had carried babies on his back, calmed witching-hour tantrums, and crouched on the bathroom floor with a sick kid at an age that I still haven’t reached.

Especially at night. My first baby slept fitfully, and by the time he finally slept through the night, the next one had arrived. Even though my kids are no longer babies, bad dreams and illness and late-night anxieties mean that sometimes we are together in the darkness. When all I want to do is disappear under the covers, I remember my dad. He was the primary nighttime parent in his 50s and 60s, the one who sat with me if I couldn’t fall asleep or if I woke from a nightmare. To soothe me back to sleep, he would often lie on the floor—it eased his back pain—and tell stories about growing up during the Great Depression, about sledding in the winter, and the neighbor who kept an alligator in the bathtub.

Worse than feeling different was feeling scared. I didn’t need another kid to point out that my dad’s time was limited. I watched him constantly and felt the swooping buzz of panic when he cut himself, or fell down, or caught a cold.

His patience was endless, timeless. The year that I was 20 and he was 73, two boys I’d known in high school died in a car accident. That weekend, my father returned to the carpet on my bedroom floor. He stayed there, telling stories, until I finally fell asleep. Thinking of him, I try to stay patient with my children in the dark, to channel that safety I always felt with him in the room.

I also think about the way parenthood has changed me—the way, at 32, my world recalibrated its orbit around this new center. But he had been 53—how much more destabilizing must it have been to have his life restructured after living on his own for so long?

If it was difficult for him, as it must have been, he never let me see it. He was endlessly curious, up for anything I was interested in. We learned together about dinosaurs and began constructing a life-size model of the Tyrannosaurus (we only got as far as the skull). He built dollhouses and treehouses. We planted corn and pumpkins and gladiolus bulbs. We took tap-dance lessons and guitar together at the local community center.

He taught me how to play badminton, to use a computer, to write a letter. I eventually did learn to drive a stick shift. He seemed to have boundless energy to spend time with me, and to take on new challenges, which I try to remember when my own energy is flagging. When he was in his 70s, he worked as a product tester for the dictation software that would someday become the speech-to-text apps people use every day; he looked through the classifieds for part-time jobs; he wrote that novel.

As my kids and I grew up together, I would often think of him when I was feeling like I’d gotten too old to try something new. If he was 55, 65, 75 and kept learning, so what was stopping me at 35, 40, 45? What would stop me in the future?

Thinking of him, I try to stay patient with my children in the dark, to channel that safety I always felt with him in the room. I also think about the way parenthood has changed me—the way, at 32, my world recalibrated its orbit around this new center. But he had been 53—how much more destabilizing would it have been to have my life restructured, had I lived it on my own, for two decades before having kids?

Recently I was walking with one of my kids when I saw an older man approaching us on the sidewalk—jaunty, smiling, plaid scarf thrown around his neck. Something about him reminded me both of my dad and the boy by my side, and I flashed back to that moment of seeing the old woman with my dad. I opened my mouth to say something similar to my son—that someday, if all went well, he’d be as old as that man.

And then I closed it. How hard had it been for me to imagine that for myself, all those years ago? How much had it felt like a slight, or a harsh reality—something to fear? Instead I thought of what my dad showed me so many years ago: that at any age, your life can change. You can learn something new, you can find someone to love, you can find joy that you never could have anticipated.

Sometimes I imagine myself back in that car, sitting next to my dad. “Someday, that will be you.” He points to the old woman outside the car window. And this time, I know just how to respond. “I hope so,” I tell him. “I really hope so.”

Lovely to see a father so engaged with his child. We often simply expect that of our mothers, but not of our fathers. It's clear that he wasn't thrown off by his late parenthood, but strengthened by it. Given, as they say, a new lease on life!

What an inspiration. I love the life-long learning and curiosity your father modeled. Thank you for sharing so we all may benefit in a small way from such a life well lived