My Cell-Cluster "Sibling" was Aborted. I’m Here Instead.

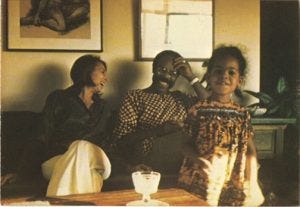

Lisa Williamson Rosenberg reflects on an illegal abortion that bought her parents time, allowing them to bring her into a world less fraught for a mixed-race kid.

My entrance to this world was deferred by 17 years, thanks to an illegal abortion my mother had in 1949 in an unmarked office somewhere on the north side of Chicago. I have always known about my “sibling”—the cluster of cells terminated that day. Despite being fiercely protective of me and filtering out certain things that might have disturbed me, such as our family’s occasionally dire financial woes, my mother was not one to sanitize stories of her own traumatic life experiences.

I once thought of her first pregnancy as a long-lost brother, someone who might appear at my door one day, 17 years my senior, having survived somehow, raised by someone else—seeking me out just to connect. The would-be-sibling was male, my imagination had dictated; in the fantasy, I was still my parents’ only daughter. Lately however, I think of the abortion as a deferment. A cell-cluster that was almost me. The baby was my father’s. My parents were not yet married; had not yet decided to marry.

I have always known about my “sibling”—the cluster of cells terminated that day in 1949.

A shotgun wedding was out of the question. No one would have endorsed that. He was Black. She was Jewish and her parents could not know about him. My mother was 22. Dad was 23. Respectable ages for parenting back then, but to raise a biracial kid in a hostile family environment in 1950? Neither Mom nor Dad felt up to that, especially having been warned by older friends, other interracial couples they knew whose mixed children were facing harassment and bullying at school, rejection by family members, isolation, and loneliness all around. “Don’t do this,” my parents’ friends cautioned. “Not even when you’re married.” Advice they took to heart, at least temporarily. Deferring the decision. Deferring me.

The country needed to cook a while longer before it was ready to comfortably host people like me, went the wisdom they were offered. Seventeen years? Perhaps longer. And at the time of Mom’s abortion, my parents were far from certain about one another. This country had not even cooked enough for my parents’ union. This was 18 years before Loving vs. the State of Virginia, which would finally make interracial marriage legal. Miscegenation was still illegal in roughly 30 states. My mother had never considered herself a trailblazer, and my father was considering a life in politics for which a white wife might not have been a great look.

So, when my mother became pregnant, there was no debate. They would find someone who could help—meaning someone capable of ending the pregnancy without endangering my mother’s life or future ability to carry a child. A safe, albeit illegal abortion.

A shotgun wedding was out of the question. No one would have endorsed that. He was Black. She was Jewish and her parents could not know about him. My mother was 22. Dad was 23.

Sure enough, my parents had a mutual friend, the woman who had introduced them in fact, who knew of someone. This friend’s father was a doctor who was acquainted with another doctor who did this sort of thing on the hush hush. (There was no other way to perform an abortion.) He was reputable, experienced, and discreet. He also happened to be an OBGYN, which gave his patients confidence. He knew his way around down there. So my mother went. My father dropped her off and picked her up when she was done. It was a relief, my mother said. She hadn’t felt any ambivalence. Though she was already teaching first grade by then, my mother had a slight dread of motherhood. She had seen up close the range of mistakes one could make, how consequential they could be for a child’s emotional and behavioral development. “I was nowhere near ready,” she always told me.

Physically, Mom remembered little about the abortion by the time I was old enough to question her about it. “Maybe like bad cramps,” was the best she could do. What made a bigger impression on my mother was what happened the day after she’d safely ended her pregnancy.

There had been a raid on the office. The doctor was arrested along with all the young women present that day, either on the table or in the waiting area. Every last one. Detained. The office closed was down, the doctor’s medical license suspended.

This was 18 years before Loving vs. the State of Virginia, which would finally make interracial marriage legal. Miscegenation was still illegal in roughly 30 states.

Had my mother waited just one day day, she would have been among those taken into custody. Had she waited two days, there would be no such reputable facility to attain the services she needed. She might have been the victim of a practitioner who used an inverted hanger or worse. She had friends, other nice Jewish girls like herself, another friend who was Catholic, who were not so lucky, suffering grave injuries as a result of their clandestine abortions. Another friend was forced by her parents to keep a child and marry the boy who’d fathered him. The child grew up in the horror of what was a long, deeply abusive marriage.

When I imagine the hypothetical life of my cell-cluster sibling, contrasting it with my own, what I feel is gratitude—not so much to him, as he had no say in the matter, no consciousness or opinion to contribute. But I am grateful to my parents, to my mother in particular, for having the good sense to override the law. She did what all women should have the right to do: prioritize her life, her relationship, and take into consideration the emotional wellbeing of my cell-cluster sibling, whose life would most likely have been miserable. I am grateful to the doctor who sacrificed his career to do what was right and good for the women who needed him to do it, despite the laws which cast his patients’ personhood aside.

What made a bigger impression on my mother was what happened the day after she’d safely ended her pregnancy….There had been a raid on the office. The doctor was arrested along with all the young women present that day, either on the table or in the waiting area.

My parents were fortunate. They grew together, learned one another, came into maturity for the full 17 years it took to get to me. I was born at a time, in a city, where biracial children were so common that if you threw a stone you’d hit six of us. Mom and Dad were “old” parents for the time, in their 40s when I was born, but ready at last for me.

Thank you Dori! We were in our own worlds back in the 80's, right? I love learning more about you too.

Elegantly written, uplifting piece. I am wondering where your parents moved to that had so many mixed race children?