Letter to My Younger Self #8: "Despite the crashes, we’ll always come back up."

Binnie Klein tells the nascent childhood poet she once was all about the songwriter she has just become, in her 70s.

Dear Younger Binnie,

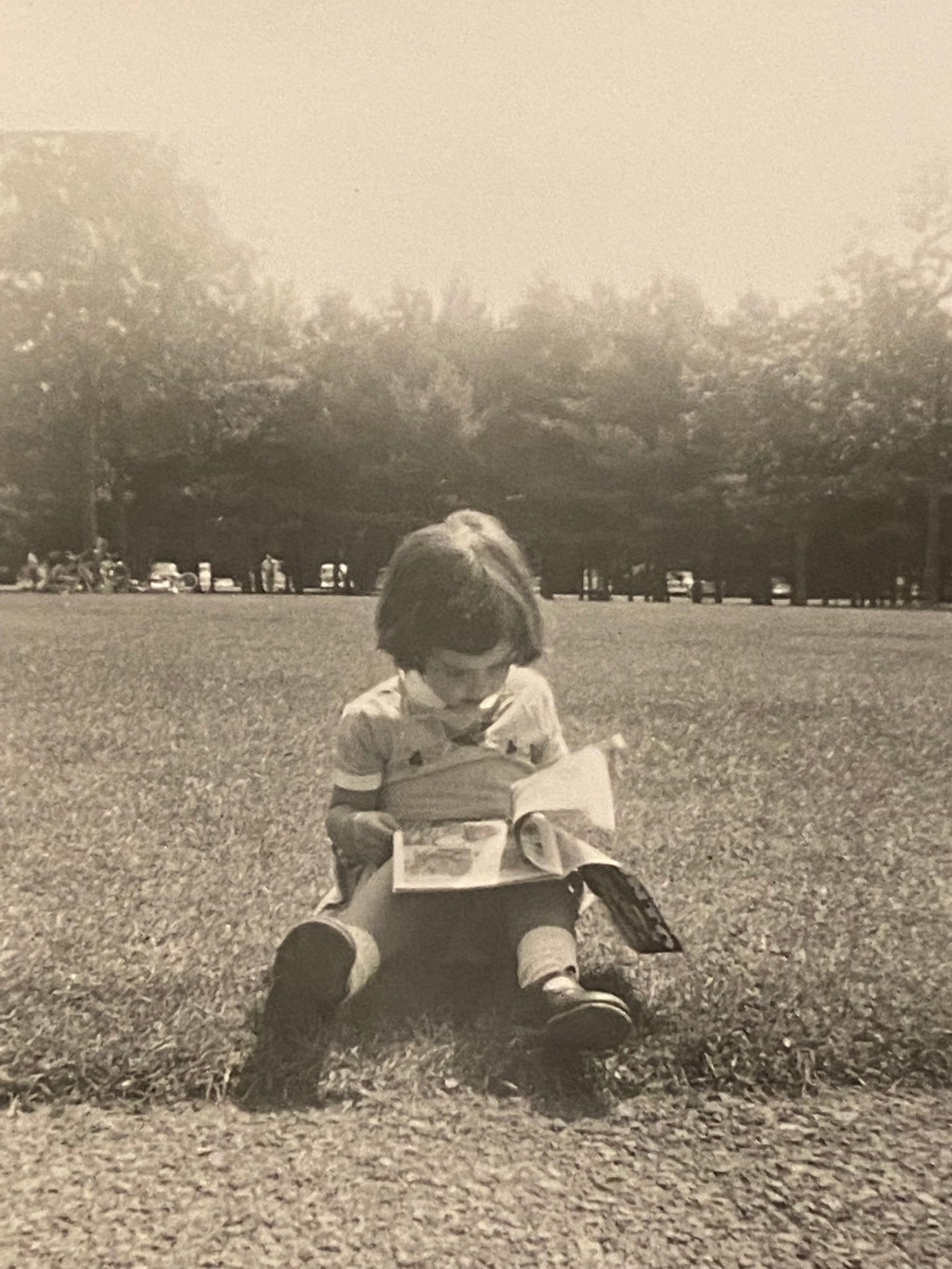

You appear to me in chunks. There’s the very young child who seems to have been lonely. You wrote about it in your first poem, titled, “Loneliness.” My father, proud that his three daughters were aspiring writers, kept the short, free verse on a torn piece of paper in his dresser drawer for years. This was the first glimmer of the songwriter I am happy to tell you I have recently become, in my third act. More on that soon…

You were a little girl who wanted things; a pink princess phone, your own television, ice skates (though you’d never skated and never would), a guitar, a bubblegum machine. You were pure id.

Though I got all those things (much to the dismay of my more obedient sisters, who called me spoiled,) we were lower middle-class, living in shabby second-floor apartments in the Jewish ghetto in Newark in the 50s, one of them above a butcher shop. We never owned a house, and our traveling salesman, horse track-betting father never saved any money. Our mother, who “came over” from Poland with her own mother on a big ship, fleeing the Russian pogroms, suffered serious depression beginning the day after I was born. Her father had suddenly died. She was afraid to hold me, and I’ve wondered how long that trepidation lasted. But at least it was a clue to my appetite for things and intense experiences—distractions from all the struggles and sadness. I asked for ballet lessons. I still have the tutu in the bottom drawer of an armoire. It’s in remarkably good condition. Red and flouncy.

Having lived through both the highs and the crashes, I could tell you, my younger self, that creativity itself will always be the sustaining thing. This drive to create, to express, to share, is a nutrient that has always been essential for my well-being and managing the darkness. I’ve found it’s the same with many other creative types—we need to have, at all times, something we’re crafting or discovering. Without it, something is missing.

I started to get rewarded in school for my writing. Maybe this was the beginning, after the acquisition of things, the beginning of what I now think of as a kind of dopamine addiction, seeking highs, and finding them in validating remarks by teachers on my English papers, and later in poetry workshops, the interest of the boys, in acting lessons, and having cool beatnik outfits for school. We know that dopamine, as in opioid addiction and cellphone scrolling, has a deep flaw—it doesn’t last, and there’s a crash when the high wears off. One feels special and fulfilled while it lasts, but it doesn’t sustain itself. It’s a constant cycle of, “I’m great/I suck, I’m great/I suck.”

Having lived through both the highs and the crashes, I could tell you, my younger self, that creativity itself will always be the sustaining thing. This drive to create, to express, to share, is a nutrient that has always been essential for my well-being and managing the darkness. I’ve found it’s the same with many other creative types—we need to have, at all times, something we’re crafting or discovering. Without it, something is missing. And yet, in the spirit of speaking truth to youth, I would warn that the creative projects can take a lot of work. They can turn out to be complicated and difficult, but in the end, the fruits of your labor are even more rewarding than it might have been to receive the princess phone and television you so wished for.

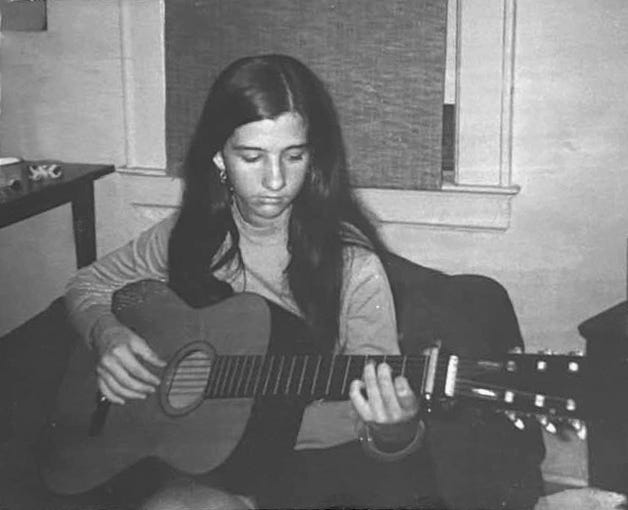

Biting off another chunk, Younger Binnie, when you’re a pre-teen, surviving various kinds of molestation that I told no one about, but also enjoying the attention of my older sister’s hip, lanky, guitar-playing male friends who were at our apartments a lot. They taught me to play guitar; I liked being their mascot. By then I was starting to find distraction from the heavy depression of our household by partying with peers, and getting caught up with the anti-war movement. I especially enjoyed the parties after the Students for a Democratic Society meetings; we’d walk to Weequahic Park, sit on the swings and smoke pot. I was obsessed with being cool, and although I wasn’t conventionally beautiful, I was told I was sexy, and didn’t want for male attention.

A high, a crash, and the sustenance of creative work; Younger Binnie, this became the repeating pattern of my life. A few years back, before I started songwriting, there was an unexpected call from my first boyfriend, who’d broken my heart at 16. We’re both married now to other people, and he lives far away. The call to inform me of a dear friend’s death activated our ghosts and our longing. We had an intense adult flirtation over text and email, until the realities of my marriage and his life as an older father of four intruded. I was crushed, but I’d been woken up, and couldn’t fall back asleep. What would I do with that renewed energy? As often in my life, I turned to a creative project. I wrote and produced a six-episode audio series, Ten Days in Newark, to try and figure it all out. I had enough skills and confidence to even attempt such a project since, from the time I was 26 to the present, I’ve been a DJ at WPKN, a freeform radio station where I produce and host a show.

Ten Days in Newark was risky. It meant phone calls with people who knew me when I was a teen in Newark, a recounting of dreams, old traumas evoked, long talks with the ex, reviewing the infatuation and the betrayals and hurt, listening to music of the 60s and 70s to grab more memories that might animate any insight I could find. In short, as I worked on this I was troubled and depressed, but I couldn’t stop. Poems poured out; lyrics of first love and first heartbreak. I started making melodies on my keyboard and pulled out my old guitar. You, my younger self, were back.

Well, sort of. The pandemic came, and proclaimed me elderly, vulnerable, compromised—a group justified in being afraid, very afraid of the virus, of being hospitalized, and possibly dying a horrible death, intubated and alone. Afterward, when others began to step back out into the world, I was leery. My hair had turned completely gray and got quite long (I’d been wearing it short) and shapeless. The existential knocks at the door, the bell ringing of mortality, was becoming less and less ignorable. I began to think about death constantly.

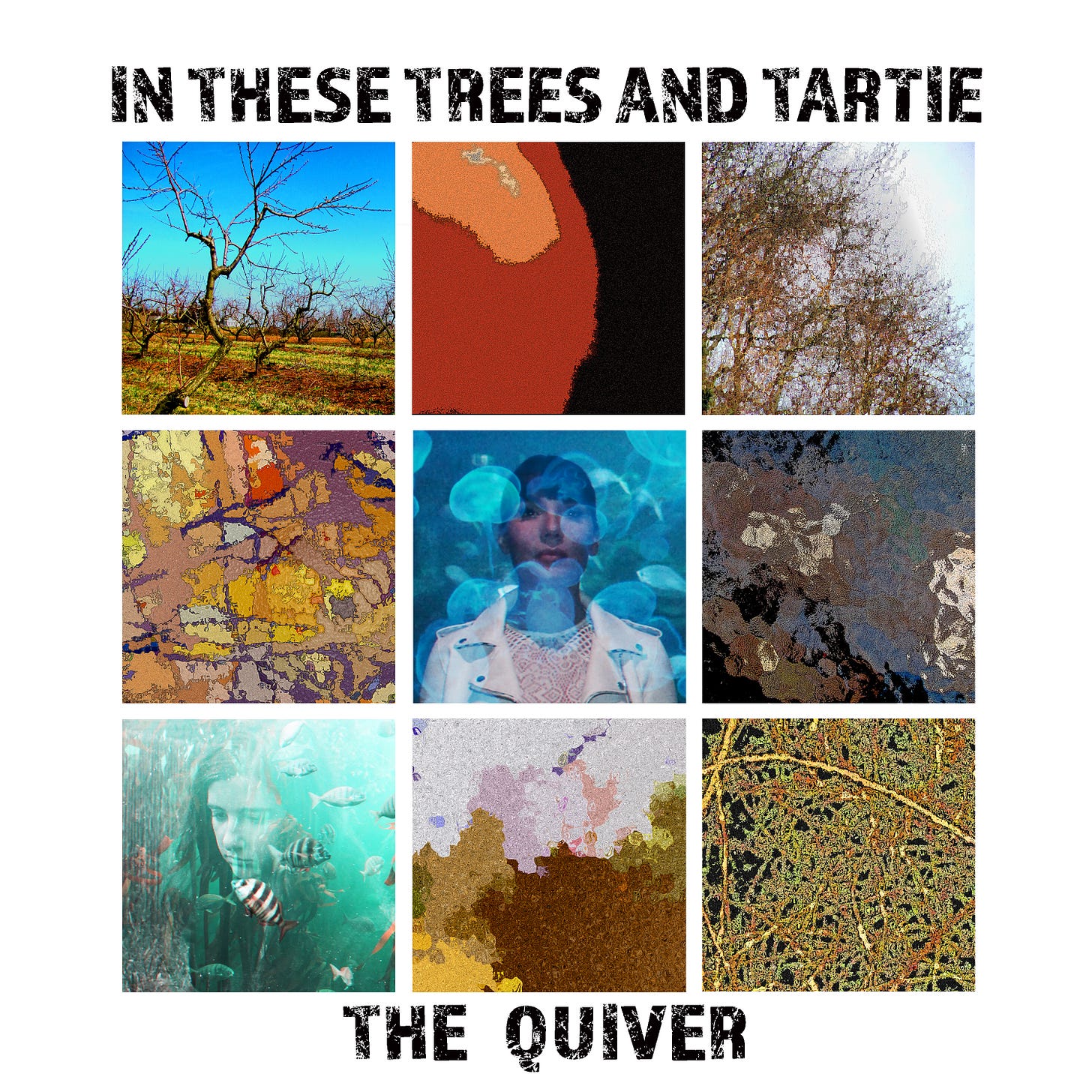

Then something completely unexpected happened. After a lifetime of deep connection to music (multiple decades as a DJ, playing piano and guitar, etc.), I became a songwriter myself. A 30-something Australian singer, Tartie, reached out to me seeking airplay on my radio show. The warmth and compassion in her singing voice thrilled me. I obliged, and then, summoning up my courage, asked if she would take a look at my new lyrics. When she returned with a demo for my lyrics to Orchard, I was flooded. I was floored. I was thrilled. I was re-vitalized. Our collaboration became a magical alchemy. I had Orchard produced, and we had an animated video made. We released it as our first single:

The songs continued to flow. We worked remotely, over 10,000 miles and three decades apart, and I arranged production (calling ourselves In These Trees and Tartie) with musicians up in Woodstock, New York. During the production of our debut album, The Quiver, Tartie had two babies. We released the album in March of 2024. The indie jungle of the new world of free streaming is a nightmare, but the reviews have been so generous and positive.

Then something completely unexpected happened. After a lifetime of deep connection to music (multiple decades as a DJ, playing piano and guitar, etc.), I became a songwriter myself. A 30-something Australian singer, Tartie, reached out to me seeking airplay on my radio show. The warmth and compassion in her singing voice thrilled me. I obliged, and then, summoning up my courage, asked if she would take a look at my new lyrics. When she returned with a demo for my lyrics to Orchard, I was flooded. I was floored. I was thrilled. I was re-vitalized.

I sometimes wonder, “Why is this happening now??” I’m so….old….now. …and there is an incessant drilling from the culture to get old well. Do it gracefully. Stay active. Don’t be isolated. Take care of yourself. Don’t complain about physical ailments. I cherish the dear friends who are making this transition with me, and how we can in fact, start a lunch date at the diner with a “check-in” about our ailments. They get it. But then the camera pulls back, and it’s absolutely surreal and disorienting. What happened to you, my sexy, leather-jacket-wearing 16-year-old self? Why do I consider my weekly visits to physical therapy to be actual social events? What has happened to sex and passion? Being in my late 60s at the beginning of the pandemic was actually my baptism into a more realistic view of my status as an elder.

I’m now over 70, sitting in a parking lot, waiting to go in for my physical therapy appointment for lumbar stenosis, wondering if people running, riding bikes and skateboarding realize their fabulous good fortune. I’m feeling a bit like Chloe Sevigny, who last June told Jennifer Testa at The Cut/NYMag, “I think aging is really one of the worst things of all time,” when suddenly, oh my god, there’s my song on the radio! And there it is….

That thrill….! It doesn’t “turn back time,” but it helps.

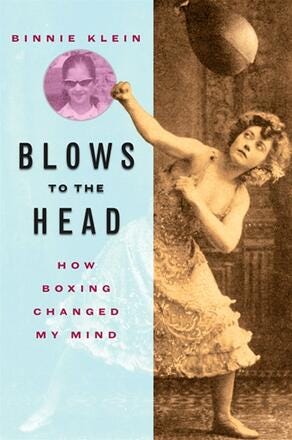

Younger Binnie, I can’t quite reassure you about the future—yours or mine—and I don’t want to lie to you, sugar-coating the struggles that come with age. But I can tell you that the little girl who wrote her first poem very young developed into someone very creative and resourceful. I’ve produced radio shows….and a book…and an album of songs. I think you would be pleasantly surprised by the songs, and proud of us, you and me.

Younger Binnie, I can’t quite reassure you about the future—yours or mine—and I don’t want to lie to you, sugar-coating the struggles that come with age. But I can tell you that the little girl who wrote her first poem very young developed into someone very creative and resourceful. I’ve produced radio shows….and a book…and an album of songs. I think you would be pleasantly surprised by the songs, and proud of us, you and me.

The results of the election and on-going wars threaten to sap my sense of hope. I wouldn’t have wished for my struggling younger self to spend her older years with this background radiation. But I must keep being creative and moving forward, as I’ve always done. So, here’s what I’m going to do: I’ve sent Tartie some new lyrics, a song called “Cherries,” about her mothering adventure. I hope she will feel a melody there and record us a demo. In a few months I hope to be collaborating with a wonderful guitarist who worked on The Quiver. He lives three hours away. This spinal thing has affected my mobility, but if I have to take a car service, I’m getting to his studio to work on my song about feminist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir.

I will get these songs produced. And I’ll hope that they reassure you, my younger self, that despite the crashes, we’ll always come back up.

I can totally relate to this while writing my coming-of-age memoir : “reviewing the infatuation and the betrayals and hurt, listening to music of the 60s and 70s to grab more memories that might animate any insight I could find. In short, as I worked on this I was troubled and depressed, but I couldn’t stop.”

I love your song let all the fruits fall down. What a discovery for me. Congratulations on finding success in your third act.

YES to all of this: "Having lived through both the highs and the crashes, I could tell you, my younger self, that creativity itself will always be the sustaining thing. This drive to create, to express, to share, is a nutrient that has always been essential for my well-being and managing the darkness. I’ve found it’s the same with many other creative types—we need to have, at all times, something we’re crafting or discovering. Without it, something is missing."