It was the fall of 1981, my senior year at Hunter College in New York City, the first day of “Workshop in Poetry 2.” I stood in a circle facing my fellow students. Our professor was a solid, African American woman her 40s. She wore clunky jewelry and a close-cropped afro. Her wire-rimmed glasses were perched at the tip of her nose. Her right breast was noticeably absent beneath her brightly-patterned dashiki.

Meet the legendary Audre Lorde.

Our first assignment was to introduce ourselves to each other in one sentence.

One sentence! I couldn’t possibly describe myself in one sentence!

“How about you?” I challenged Professor Lorde.

Unruffled, she stared me down and propped one hand on her hip. “I am a Black, militant, lesbian poet,” Lorde told me. Her unspoken question back my way was, “And who are you?”

“I am a Black, militant, lesbian poet,” Lorde told me. Her unspoken question back my way was, “And who are you?” I can’t remember my response, but I will never forget hers.

I can’t remember my response, but I will never forget hers.

Thus began the semester-long parry between the godmother of activist spoken-word poetry and me. I was probably Lorde’s worst student. Not that I was a terrible poet, but I constantly butted heads with her. About everything.

Like a true 20something, I was pissed off that she gave us homework assignments in addition to all the writing we did in class. Situation poems. Sonnets. Free verse. Why was she so demanding? Didn’t she know I was juggling five other classes and worked part-time?

And what happened to last semester’s sweet, hippy-dippy grad student poetry teacher? She of the long, flowing, ethereal curls and the eternally-sunny disposition. Ms. Reid thought all our literary efforts were “cool” and “nice.”

At the time, I had no frame of reference who this Audre Lorde person was. I was a clueless kid from working class Brooklyn, whose family didn’t know from poetry. I came from simple people who were perplexed by the budding writer they’d been saddled with. They thought: Who had time for poetry? Who made a living from writing? Writing wasn’t a career! A secretary, or a schoolteacher, now those were careers. Why was I so difficult, so weird, they wondered? My parents didn’t know what to do with me.

But Lorde did. When Lorde suggested a piece could benefit from editing, I responded with, "That’s the way the poem came out.”

“A poem is not a bowel movement,” Lorde said calmly, unwilling to accept lazy excuses. “It doesn’t just come out. Do another draft.”

I did. She was right. It was better.

Then there were Lorde’s pleas not to handwrite my work in fine-point pen. “I grade my students’ work at night,” she explained. “By then my eyes are tired.” To further plead her case, Lorde drew a set of droopy eyelids in green at the top of one handwritten poem. Reluctantly, I switched to a thick, blue Bic for her benefit.

I had no frame of reference who this Audre Lorde person was. I was a clueless kid from working class Brooklyn, whose family didn’t know from poetry. I came from simple people who were perplexed by the budding writer they’d been saddled with. They thought: Who had time for poetry? Who made a living from writing? Writing wasn’t a career!

One day, Lorde gave an assignment to write about anger. For years, I’d been struggling with my Jewish boyfriend’s mother rejecting me simply because I was Catholic. I wrote a poem that compared Mrs. Tavel’s blind prejudice to “meat stewing in its own grease.” In the corner of my paper, Lorde wrote “Yes!!!!!” underlined twice. She understood.

Not counting her seven-word intro to us that first day of class, I knew that Lorde was different. Once, when the class was discussing our weekend plans, I asked Professor Lorde what she’d be doing. “Celebrating the winter solstice,” she said plainly.

I didn’t know anyone who celebrated the winter solstice. But then again, I didn’t know anyone like Audre Lorde. And I never again would.

Little did I know that Lorde wasn’t simply teaching me about poetry; she was teaching me about life. By her bold example, she demonstrated how to live unapologetically. To say what I thought. To stand behind my words.

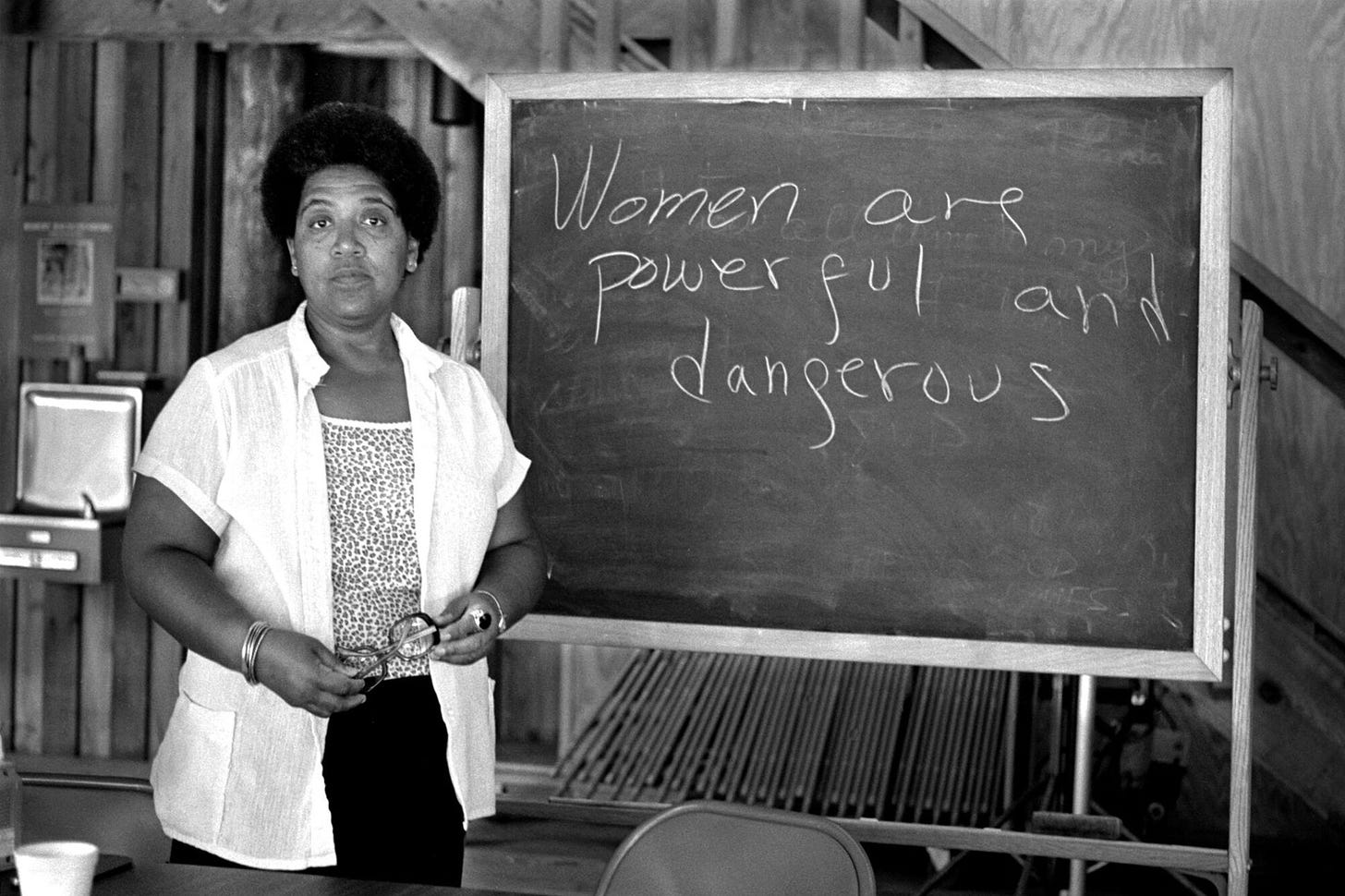

There’s a famous photo of Lorde standing in front of a blackboard upon which she’d scrawled, “Women are powerful and dangerous.” In the picture, she stares back at the camera with her eyebrows slightly raised, her forehead furrowed, much the way her gaze confronted me that first day of class.

Alexis Pauline Gumbs’ recent imaginative, lyrical biography Survival Is a Promise: The Eternal Life of Audre Lorde got me thinking more about Lorde and how lucky I’d been to study with her. Gumbs’ book also drew parallels between Lorde’s life and mine that I hadn’t known when I was her student.

Little did I know that Lorde wasn’t simply teaching me about poetry; she was teaching me about life. By her bold example, she demonstrated how to live unapologetically. To say what I thought. To stand behind my words.

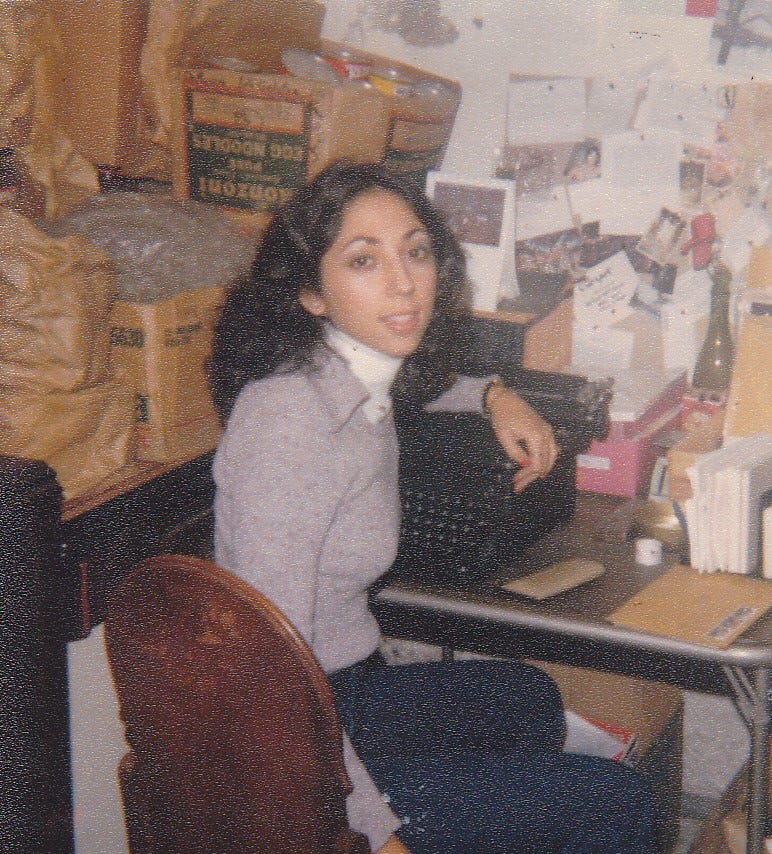

For instance, we both (partially) supported ourselves while going to Hunter by freelancing for Seventeen Magazine. I also cut my poet’s teeth writing sci-fi, as she did.

In Survival Is a Promise, Gumbs writes that while teaching at Tougaloo College in 1968, “Audre fell in love with her students.” Lorde described them as “a group of young people writing with great pride, excitement and power.” I hope she felt that way about us at Hunter.

Decades later, in 2013, I was diagnosed with breast cancer, just like Lorde had been in 1978. (Six years later, it metastasized to her liver.) I wished I were brave enough to face life without a breast prosthesis as Lorde had done. She confronted the world, even in her author photos, minus a fake breast. As if to say, “This is me, like it or not.” Instead, I wrestled with reconstructive surgery that failed, and now wear a silicone gel breast form, still too scared to “go flat.”

More than 30 years after her 1992 death, Lorde’s The Cancer Journals brought me solace. Originally published in 1980, Lorde dares women with cancer to defy it, not to let it consume them or define them. The book is a how-to on being insolent in the face of illness, how not to give in.

In 2013, I was diagnosed with breast cancer, just like Lorde had been in 1978. I wished I were brave enough to face life without a breast prosthesis as Lorde had done. She confronted the world, even in her author photos, minus a fake breast. As if to say, “This is me, like it or not.” Instead, I wrestled with reconstructive surgery that failed, and now wear a silicone gel breast form, still too scared to “go flat.”

Looking back, the least of what Lorde taught me was poetry; the greater part was how to live. And how to die. In her essay collection A Burst of Light, Lorde says, “I’m going to write fire until it comes out of my mouth, my eyes, my nose holes. I’m going to go out like a fucking meteor!”

And she did. Though cancer ravaged her body, Lorde fought. She lived out her days on her own terms, in St. Croix, returning to her ancestors’ island roots, swimming in the warm Caribbean. She continued to create. She continued to inspire. She still does, even more than three decades after her death.

After graduating from Hunter College, I eventually became a journalist and a poet. (And a two-time breast cancer warrior.)

I wonder if Lorde would edit my poem “Reflections on a Black, Militant, Lesbian Poet.” Would it be riddled with her bright green chicken scratch? Or would Lorde simply sit and nod, smiling her beneficent, brown Mona Lisa smile, silently proud of what she’d helped me become.

PS, I got an A in her class.

The teachers you remember are always teaching life. “A poem is not a bowel movement”: priceless.

“A poem is not a bowel movement,” Lorde said calmly, unwilling to accept lazy excuses. “It doesn’t just come out. Do another draft.”