Here’s a scene:

I have taught myself to skate on a frozen pond in Boston. Frontward crossovers. Backward crossovers. A mini waltz jump. A halting spiral that bumps across the twig-flecked ice, both arms out for balance.

But now I’m a lesson taker on a regular rink in Wilmington, Delaware, and there are expectations. I am to improve each week. I am to add to my arsenal of jumps and spins, perform to music cut specifically for me, get ready for the coming competitions. I am, I think, doing my best, but my coach has other opinions. One day, secretly, he films me during practice. Then, when it is lesson time, he presents his verdict on his handheld camera. I am the girl refusing center ice. I am the girl hanging back at the boards. I am the girl watching the other skaters leap and swirl, as if that will help me land my axel. He thinks I’m lazy.

I want to tell my skating coach that I am having trouble. That when he talks me through footwork, when he shows me himself, when he tells me to do what he tells me to do, something catastrophic happens. Something that feels hot and trembling inside. Something that beleaguers all learning. And so I watch the other skaters glide and rise. I watch, so that I can learn sideways. This will become the determining pattern of my life.

I am horrified. I am panicked. I am exposed. What will be said to my father, who is working long days so that I can belong to this rink and take lessons? What will be said to my mother, who drives me to the club, then drives home and then drives back, with dinner and two other children waiting?

I want to tell my coach that I am having trouble. That when he talks me through footwork, when he shows me himself, when he tells me to do what he tells me to do, something catastrophic happens. Something that feels hot and trembling inside. Something that beleaguers all learning. And so I watch the other skaters glide and rise. I watch, so that I can learn sideways.

This will become the determining pattern of my life. On the tennis court with the tennis coach I cannot fathom the grip he’s demonstrating. In the ballroom with the tango teacher, I step back to catch my breath over the bewildered pummel of my heart. My husband tries to teach me Spanish—his language, our son’s ease—and all I hear is commotion in my ears. In winter cold during a raku firing, I extinguish my miniature flame too soon. “But I said,” the teacher says, and I answer, “I know, I know, I’m sorry.”

By the time I turn to paper arts, just after I turn 60—gelli printing then binding, paper making then cyanotyping then origami folding then collaging—I am a dogged autodidact, stuck inside my hapless ways. My artist husband knows to leave me alone—to offer encouragement but no rules, to say, occasionally, You know there is a color wheel, to allow me to shrug off that news. I will learn color on my own, the proper angle of an X-Acto blade, proportions, positives/negatives, the journal stitch, the weights of papers. I will buy how-to books but will fail at the instructions. I will watch YouTubes in utter exasperation. I will toss the poorly coptic-stitched book across the room, wipe away the tears, rise, take all the stitches out, and try again, because through all these years of learning lonesome, learning sideways, I refuse to be defeated. I will not allow whatever is different in my brain—the chemistry of anxiety, an undiagnosed faultiness in my wiring—to thwart what I desire.

The years have taught me to keep going.

The years have given me no other choice.

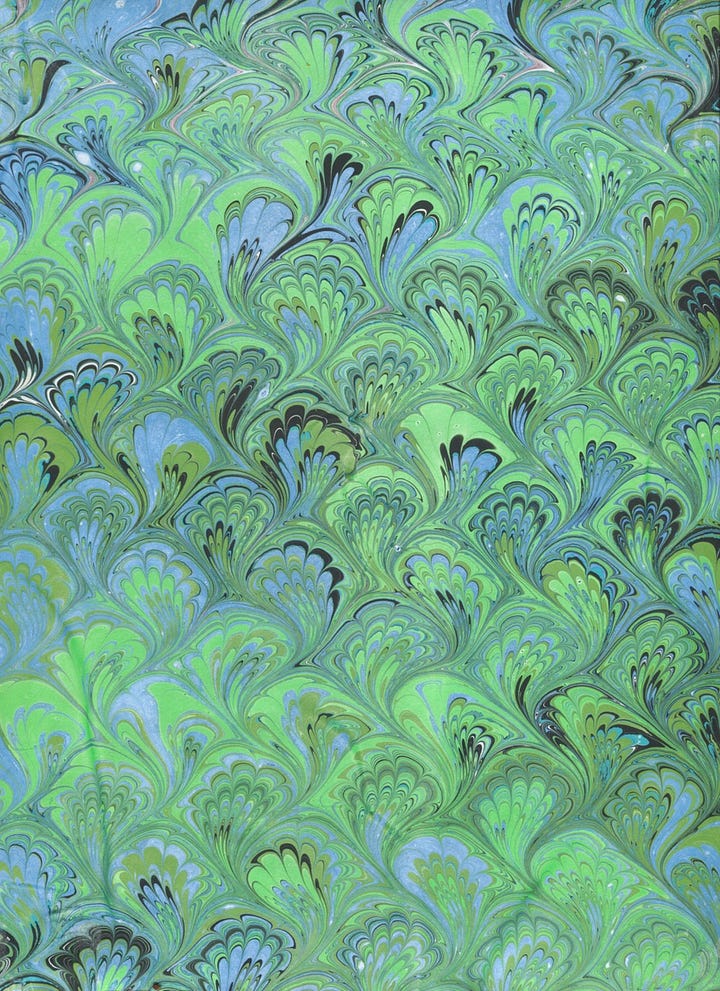

One Christmas my husband buys me marbling paints and a tray, carrageenan, alum, broom bristle tips, raking tools. The gift comes with a how-to book, and I dutifully thumb through the pictures. But then (after my husband mixes the carrageenan and the alum as I am not always the best at math) I am on my own. I am marbling paper.

Another something new.

Another stoking of the searching in my mind.

By the time I turn to paper arts, just after I turn 60—gelli printing then binding, paper making then cyanotyping then origami folding then collaging—I am a dogged autodidact, stuck inside my hapless ways. My artist husband knows to leave me alone—to offer encouragement but no rules, to say, occasionally, You know there is a color wheel, to allow me to shrug off that news.

In my kitchen I stand over the shallow tray of carrageenan, upon which the colors will float. I open the jars of acrylic tones and hues, and choose my first marbling palette. I dip the first broom bristle tips into the first jar of color and then, using a motion I decide is just right, flick the color across the surface of the carrageenan. The color blooms, each small dot spreading out from itself. This is the process I now repeat—the next color, the next color, the next, all these intersecting, overlapping blooms—until (I assume) there is enough density of color.

Now, up and down the tray I run a short dowel stick, drawing the colors together into new patterns. Now I take the raking tool—a wooden bar into which nails have been evenly spaced—and move it lengthwise across the surface.

I stand back.

I lay a piece of alum-ed paper face down upon the colored surface.

Pull it back up.

Rinse it clean.

Study the patterns the paint and bristle tips and rake have made.

Leave it to dry on a plastic cloth on the kitchen table.

I cannot—I never will be able to—explain this. How quieting it is to watch the colors as they spark and mix, to watch as paisleys, bright zags, celestial signifiers lift from the tray and rinse and hold. My table is big enough to fit thirteen sheets and five short sheets of freshly marbled paper, and so, those sheets in, I quit. But in the days to come, I won’t stop dreaming about marbling. I will, repeatedly, begin again.

When whatever is tricky inside your brain requires you to teach yourself most things, when this has been your way of things since you can (you try to) remember, when you have found yourself alone at the precipice of both frustration and wonder, it is difficult, at least it has been for me, to trust your final product. To believe the art is fine, or the stitching is just right, or the colors you have chosen are purely pleasing.

Perhaps, you think, that, even though you have relentlessly grown older, you will never finally actually grow up. That you’ll never really know.

I have been marbling paper for a few years now, but I’ve never been quite certain of its “rightness.” I have assumed that the small smudges of color by the paper’s edge are proof of my amateur status. That those white dots that sometimes appear are evidence of error. That when some of the color crawls onto the back side of the page I have managed to do something shameful.

It’s okay, I have told myself. It’s the best I can do with the brain I have been born with. It’s okay, I am still growing older, growing up.

But here’s a scene, from just weeks ago: It’s a gray and rainy day in Florence, Italy. The crowds are everywhere, and they are pressing. In a fit of claustrophobia, my husband and I slip inside a paper shop, where they sell the work of expert paper marblers for expert marbled paper prices.

I stand at the drawers, studying all the gorgeous papers, choosing which three I’ll carry home. I stand there, tears in my eyes, seeing something newly. There are smudges of color at the edges of some papers. There are white dots that float across the paisley patterns. There are crawls of color on the back sides.

I have learned sideways, I realize, but I have also learned well. And there’s still room to grow.

stunning absolutely marvelous

Beautiful feeling in the world to have things align and fall into being, just right for one.