I'm Retiring. Shouldn't I Be Celebrating?

Michèle Dawson Haber examines the connection between her mother's decline and her mixed feelings about ending a chapter in her work life.

Ah, retirement. After working 24 years as a labor advocate, the milestone has arrived. I’ve been laying the foundation for a few years, planning a future when I can write, play in my pottery studio, and do some consulting. Psychology researchers who warn against retiring to nothingness would nod their heads in approval—I’m doing everything right. “You’re so lucky,” say my friends, without exception and regardless of age. “And so young!” I know they’re right. How many people get to retire at age 56 with a pension? Few people are so fortunate. Fewer still think I should follow up all this with a “But—"

But…now that the moment is at hand, I feel on the cusp of loss, despite being certain that this is what I want. Sure, I’ll miss the work and my colleagues, but the anxiety I feel is bigger than that. I know I need to stop moping and pirouette into my blessed new life, but first, I want to figure out what it is I’m losing.

Maybe to me, Retirement = The Loss of Purpose. Like many, my work is a big part of my identity. I am an advocate, researcher, and writer representing unionized healthcare workers, helping them achieve fair and generous working conditions (such as the opportunity to retire early). It has been my dream job, allowing me to apply my values of justice and equity in concrete ways that make a difference in the lives of workers. Twenty-four years is a long time to do the same job, and, as good as it was, I want to try new things. But when I step aside to let someone else take over my role, what purpose will I serve? So much of who I am today is a result of the skills I developed in my work. Will the qualities that allowed me to excel in my job—dogged insistence on fair treatment, the need to understand all sides of a problem, strong communication and persuasion skills—remain, even if I don’t call upon them in the service of paid employment?

I’ve been laying the foundation for a few years, planning a future when I can write, play in my pottery studio, and do some consulting. Psychology researchers who warn against retiring to nothingness would nod their heads in approval—I’m doing everything right.

But the possibility of no longer feeling useful doesn’t explain all my angst. Maybe it has to do with aging. Even though each year I worked I was that much older, I believed I was pushing off Old Age to some amorphous point in the future. I worried about it though, and did everything to keep it at bay, using anti-wrinkle cream since my 30’s, saving for the future, lifting weights, and reading any article with dementia in the headline. Whenever I was in a group, I’d scan its members to assess everyone’s age and, if I wasn’t the oldest, I’d sigh in relief.

So, does Retirement = The Loss of Youth? Will I wake up on my first day of freedom and find myself with a bad hip, chin whiskers, and no idea who that man is sleeping in my bed? (Actually, never mind the chin whiskers, they moved off The Pleasures That Await list a while ago.) Ridiculous, of course—but just because something is illogical and irrational, doesn’t mean I’m above worrying about it.

I wish I could ask my mom these questions, but she has Alzheimer’s and is no longer capable of cogent advice. Besides, her work experience was far different from mine. She had a variety of different jobs throughout her life, both paid and volunteer. Neither my mom’s mother nor her grandmother had careers, never mind a pension plan. I’m the first female in my family line to retire from a full-time career. There is no one to give me guidance on how to navigate this huge change in my life.

Now that the moment is at hand, I feel on the cusp of loss, despite being certain that this is what I want. Sure, I’ll miss the work and my colleagues, but the anxiety I feel is bigger than that. I know I need to stop moping and pirouette into my blessed new life, but first, I want to figure out what it is I’m losing.

Perhaps the weight of time passed is felt only when you realize you can no longer depend on your parents for help. I have only memory and imagination to call upon now. Dad died in 2008, and six years later mom moved to a seniors’ home closer to me and my sister. She was not in favor of it, but the doctors who diagnosed her gave her no choice. The milieu of the home was depressing and spiritless, and in her funny t-shirts and glittery tennis shoes, my mother didn’t match the other residents. After a couple of years, she got a walker and didn’t rotate her t-shirts as often. When visiting, I watched the residents shuffle from the elevator with their walkers looking miserable, confused, or both. Now, my mom looks that way too, and it scares me.

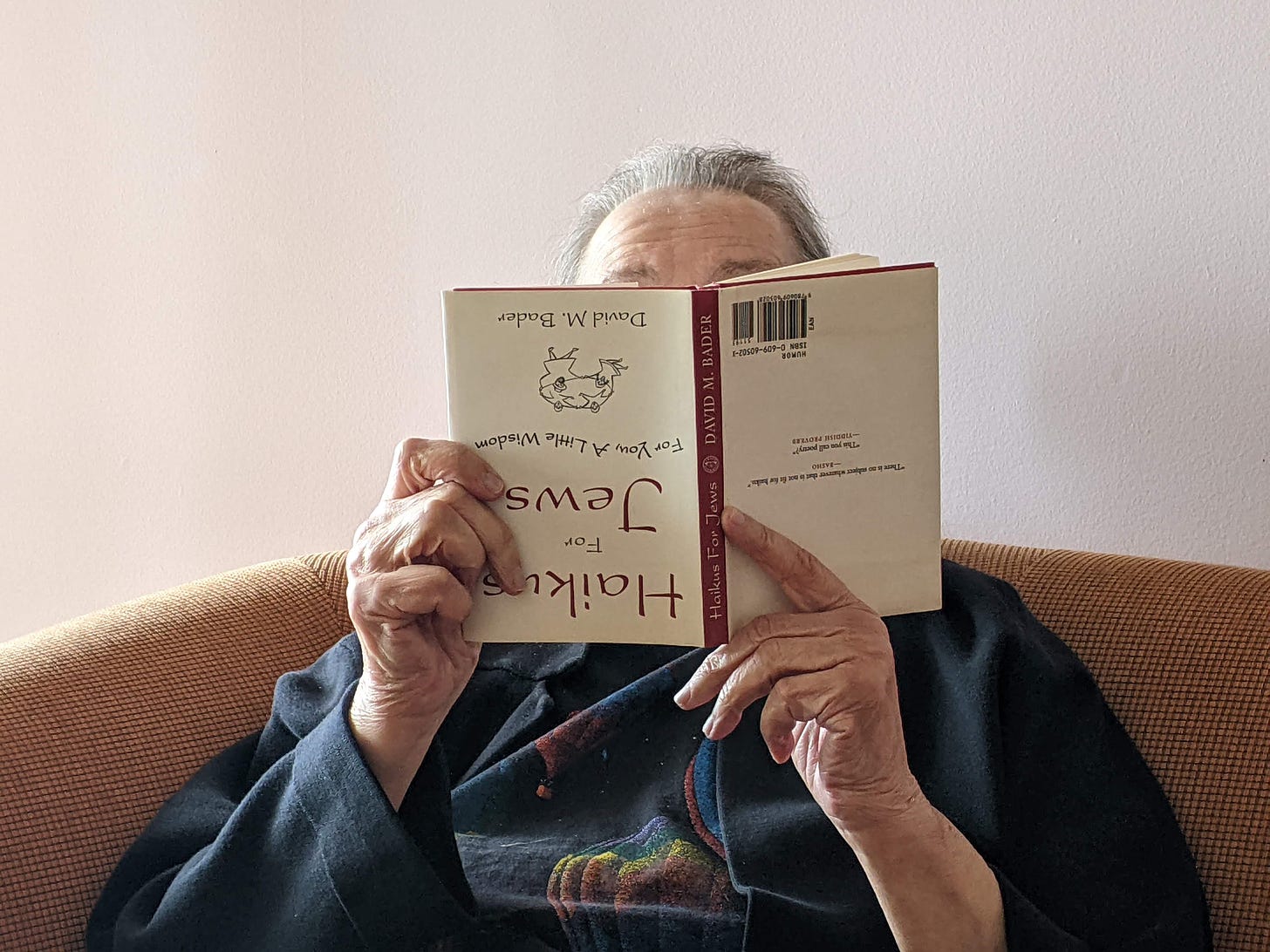

Gone is the woman who had such strong opinions about interior decorating that she would hold out for months until she found the perfect burnt-orange and turquoise accent pillow for her sofa, who could get the same enjoyment from reading Chekhov as a popular murder mystery, who collected doll house chairs and novelty salt and pepper shakers, whose cred as a hard-core feminist dated back to the 70s when she wrote for and edited a prominent women’s newspaper, who loved both neon art and opera, and whose sarcastic humor was legendary. She did not embrace many conventional mothering roles, but advice-giving was one that she took very seriously. If I told that woman that I feared retirement would hasten my old age and exile me to a state of everlasting irrelevancy, she’d respond, “Get a grip, you’re only 56!” She would then rhyme off all her heroines who accomplished remarkable things later in life and follow up with a long letter refuting all my assertions, attaching relevant scholarly articles. Oh, how I miss that mom.

In late June, I joined her at the seniors’ home for dinner. She was wearing her black t-shirt that said, "Start your day with a smile—and get it over with.” Every few minutes her tablemate, Phyllis, looked at her watch, announced the time, drummed her hands on the table, and read from her pill packet. “S-U-P-P-E-R. Supper. June 25, 2022.” I looked at my mom through the plexiglass table divider meant to keep the residents safe during the pandemic. Her face was blank—she seemed not to be registering anything, certainly not Phyllis. Then, something extraordinary happened. Suddenly too warm, I lifted my hair off my neck into a ponytail and then wiped my forehead with a napkin. My mom, noticing my discomfort, raised her eyebrows. “What?” she mouthed. “Menopause,” I mouthed back. She nodded, answering, “Say no more,” and gave me a huge grin. It was as if a window shade had been lifted, filling our table with light.

I wish I could ask my mom these questions, but she has Alzheimer’s and is no longer capable of cogent advice. Besides, her work experience was far different from mine.

Growing up, “Say no more,” was an oft-heard expression in our home. It was said in a feigned Wise Man voice, usually with a palm raised toward the speaker and face averted to the side, signaling that further awkward explanation was not necessary. This expression was always followed by giggles. When my mom said it that day, I knew she was still in there, fighting to keep herself. And I was relieved.

But it was just a quip—why did it prompt such relief? Then, it hit me. The loss I’ve been struggling to name: Loss of Self. I’d been mourning the quickening disappearance of the mom I’d always known, and fearing I’d end up just like her. But in that moment of lucidity I saw that she was still present, and I was glad for her and hopeful for me. Even as the Alzheimer’s works to dismantle her memory, confidence, and cognitive abilities, it has not yet succeeded in fully extinguishing her essence.

She doesn’t know it, but my mom has helped me after all. I was wrong to conflate retirement with aging, disease, and loss of self. Especially retirement at age 56. My identity is intact, and I have my health, talents, and dreams. Surely, if my mother, with far less going for her now, can muster the courage to persevere each day, I can triumph in retirement and continue to strive in new ways in my 50s, 60s, and beyond. (“That’s right,” I imagine her saying, satisfied that I’ve listened to her wise counsel. And then she’d add, “and don’t call me Shirley!”)

The loss I’ve been struggling to name: Loss of Self. I’d been mourning the quickening disappearance of the mom I’d always known, and fearing I’d end up just like her. But in that moment of lucidity I saw that she was still present, and I was glad for her and hopeful for me.

Retirement ≠ Loss of Self.

Ah, change. How hard it is! But change need not equate to loss. I associated retirement with losses that existed only in my mind. In fact, I will be no less skilled and useful on the day I stop work than I was the day before, when I was a mere 24 hours younger. I don’t need to worry about holding onto youth, being productive, or staying relevant for others, because that has nothing to do with who I am. I resolve to leave all my imaginary losses by the side of the road. I will one day encounter actual loss, but when I do, it won’t be because I’ve invited it in.

I’m eager to see where I take my life from here. I might as well dance into retirement, arm-in-arm with all the women in my family—past and present—cheering me on. As long as I can hold on to my true essence, I’ll have reason to celebrate.

This is a beautiful piece. I'd love to wish away the chin hairs but alas they're inevitable and the last exfoliation my mother requested before she died, "Could you shave my mustache?" Now, at 77, I've published my debut with Woodhall Press--there's No Expiration on Dreams. Dream on...

Very well written. I’ve had a similar experience. Alzheimer's disease Is horrible. I was in engineering software. When I retired I became a farmer. I grew raspberries for farmer’s markets. Did it for 12 years. I have to admit, it was the best career so far. Celebrate. You get to reinvent you if you want to!