How to Embalm Yourself Before You're Dead

Nine months after her mother's passing, Michelle Dowd sees her father in a new light.

Since Mother’s death, I’ve been mothering Dad the way I’ve always wanted to be mothered. I learned to be a mother by caring for my younger siblings and newborn cousins in the cult into which I was born, until I partly grew-up and had four children of my own.

I was never a child.

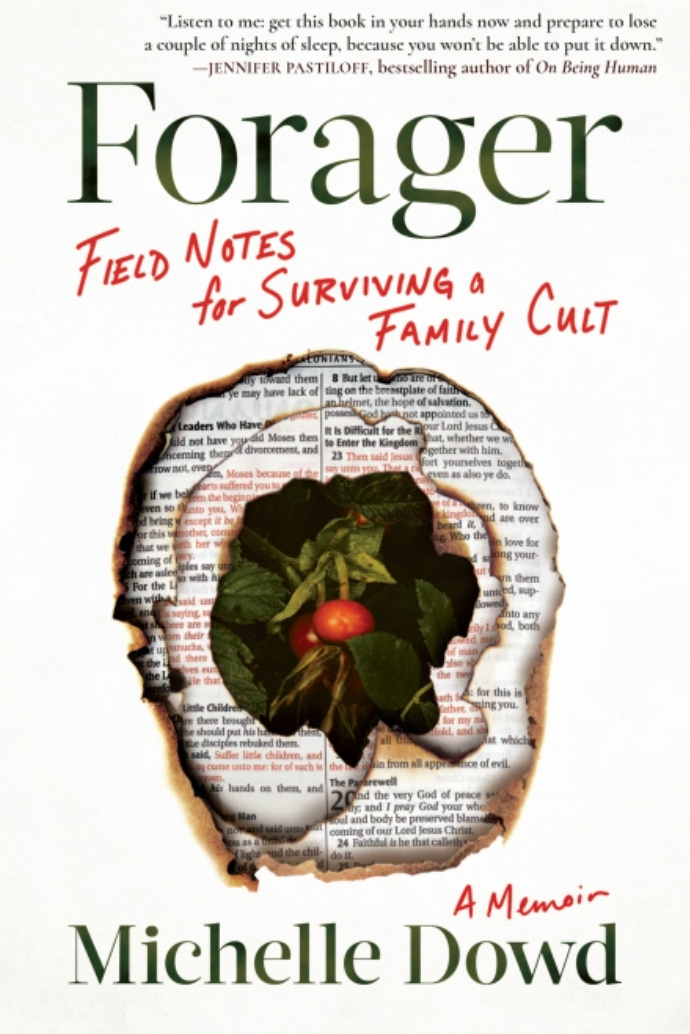

I grew up on a mountain, preparing for the Apocalypse, by parents and grandparents who believed the end of the world was nigh. We slept on army bunks, walked down the hill to the outhouse, and foraged for seeds. Part of our preparation was learning to survive off what the Mountain would yield. The other part was becoming a soldier in the army of God.

It took me a long time to recover from that way of thinking. If I even have.

I wonder how long it will take Dad to recover from Mother’s death. Or if he ever will.

He didn’t want to stay in their home after she died. Within two months, he moved into a single room in an assisted living home near where he and Mother had first met. I’ve been visiting him regularly for the past six months, but today is special. He’s invited me to his volleyball game.

“Your father is quite the athlete,” Linda says to me, nodding in his direction, “they don’t make ‘em like that anymore.”

I learned to be a mother by caring for my younger siblings and newborn cousins in the cult into which I was born, until I partly grew-up and had four children of my own…I was never a child.

My 85 year old father has just spiked a beach ball over the net for his team’s win. He’s very good at this chair volleyball thing, and I’m pleased to see how much this co-ed team adores him.

Of course, working as a coach his whole life has given him an edge. He approaches life as sport, and winning is everything.

“You should have set me up better, Linda, you practically sent that last one into the net. We almost lost because you don’t hustle! You need to work on that.”

“Does he always order you around?” I ask Linda, who appears to be in her late 80s.

“Yes, he does,” she says, “but he’s a card.”

It bothers me that he still orders women around, but decades of asking him not to has never done any good. He speaks this way to me, too.

As we walk to lunch, Dad stops in the hallway and knocks loudly on a door. It takes a long time for anyone to answer and I feel certain we’re being disruptive. When I tell Dad we should leave, he orders me to stop talking. When Bonnie finally opens the door, he calls her a little old lady and tells her to pick up the pace next time, or he won’t wait. She apologizes and explains to me that she lost her husband four months ago and it’s been hard to get her head straight. Dad tells her to stop making excuses.

Bonnie steps out and knocks on the door next to hers and introduces me to her fraternal twin sister Betty, who lost her husband twelve years ago. She tells me they haven’t lived this close to one another since college and I smile. I tell her I have fraternal twin daughters, who live next to one another with their husbands. Bonnie says, “I know. Your father told me.”

I wonder what else Dad has told her.

“You must be so proud to have a daughter who makes time for you,” Bonnie says. Dad grunts.

“Michael, tell her you’re proud of her. I want to hear you say it.”

Dad grunts louder, “What’s there to be proud of?”

Since I’ve been an adult, the only time I’ve engaged in a sport with Dad was at Mother’s insistence, while she lay immobile in the early stages of dying. She sent us out to the on-site golf course, saying Dad needed it. It was my first time attempting golf, but that didn’t lower Dad’s expectations. He took me to the driving range and yelled at me to keep my eye on the ball, shoved me with his hip to correct my stance, and as he ordered me to hit hundreds of balls I had no interest in hitting, he explained to me the purposes of the different clubs. He said he wouldn’t let me onto the course until he was convinced I wouldn’t embarrass him.

He didn’t want to stay in their home after she died. Within two months, he moved into a single room in an assisted living home near where he and Mother had first met. I’ve been visiting him regularly for the past six months, but today is special. He’s invited me to his volleyball game.

When he finally allowed me on the grass, I focused and did my best to be accommodating. I didn’t hit any golf balls into anyone else’s carts or bodies, nor plummet any into the decorative ponds. I even made par on a couple holes. As we drove back to Mother in his golf cart, Dad didn’t say I did a good job, but he wasn’t yelling, so I took that as a win.

“You’re lucky to have a daughter like that,” Bonnie tells him, “Tell her you appreciate her.”

Dad shrugs and we walk away. “I don’t know what she sees in you,” he says.

He’s always been a man’s man, working among men, as a field hand, mechanic, and football, basketball, and baseball coach. My femininity is something Dad can’t forgive, but I hang onto it anyway.

“Ladies love me, Dad,” I say. “You’ve just never paid any attention to what ladies love.”

But ladies love him, too. I’ve always known this. A head taller than most, with a barrel chest, and hair all over like an ape, he has a bold masculinity that’s almost outrageous. I’ve often blamed his anger and violence on his testosterone levels. My friends used to say that he was scary, like a bear, which I think is an understatement.

Mother died at home nine months ago. My parents were married for fifty-five years. I wonder if Bonnie knows that.

We make our way to the tiny two-person table Dad has reserved. I realize we’ve never eaten a meal together, just the two of us. He seems comfortable with me in a new way. Maybe it's because I smell like Mother. Lately, I’ve been using the Fructis hair conditioner and L’Occitane lavender hand lotion she left behind. Today I even put on a touch of her mocha lipstick.

Mother died at home nine months ago. My parents were married for fifty-five years. I wonder if Bonnie knows that.

“Mr. Dowd looks like he’s on a date,” observes a woman in a large hat, sitting at a table adjacent to ours.

“Mabel, this is my daughter Michelle,” Dad says, “I don’t want any of you hens spreading rumors.”

“She’s cute,” Mabel says.

Dad doesn’t hear her, or at least, pretends he doesn’t.

Pictures of my dead mother’s body pop up sometimes when my phone sends me memory montages. It’s jarring, but I don’t know which to delete, which to keep, what’s inappropriate or disrespectful, if or when or where to file them.

While Mother lay dying, I lived fifty-five minutes away from her, closer than any of my siblings, so I was there with my brother during her passing. I lay with her on the hospice bed, holding her hand, my head on her heart, as she drew her last breaths.

And I stayed after, obeying Dad’s orders, cleaning out things he could no longer bear to look at. “You remind me of my mom,” he said to me then. I took this as a compliment, since his mom was living with them when she died at 92, still spry and full of her faculties.

“You take care of me the way she did,’ he said, and he started to cry. “It’s like I’m your child.”

I gave him a hug and he pushed me away. “This is embarrassing,” he said, “I’m a grown man, I’m not supposed to cry.”

I brought him water and a handkerchief and I sat down on the floor next to his chair, while he wiped away the residue of his tears.

The day after Mother died, Dad walked into the bathroom and came out holding stacks of Tupperware boxes. “Take these,” he said, “I don’t want them. Do whatever you want with all of it. I don't want any of it here.”

I nodded and opened the lids. Mother had more toiletries and cosmetic products than I could have imagined, not having watched them accumulate over the years.

When I was a girl, Mother said she didn’t believe in cosmetics, or the wiley ways of women. I don’t know when this changed. Until Mother lay dying, I hadn’t slept in my parents’ home since I was 17.

Some of her products were dusty. I touched the edges of the lids. Ashes to ashes, dust to dust, dust in the wind, everything turns to dust.

As I got ready for Dad’s volleyball game, I used Mother’s body wash, her shampoo, her conditioner, her blow dryer, her comb. I used her toner, her facial and body lotion, her sunscreen, foundation, face powder and the lightest mocha lipstick she had in her collection. I pictured her using each of the products, imagining her getting ready with me. Each application felt like a ritual, like I was embalming myself with a wordless love.

I put the Tupperware boxes in a large trash bag to throw away. I went out to the garage, but Dad’s trash bins were overflowing, so I put the bag in my car. When I got home, I put the bags in my grown son’s empty closet. I told myself I’d look through them later.

The night before Dad’s volleyball game, I went through the bag of Mother’s sundry items, fingering the products she must have thought would make her clean. I think about how she soiled the sheets, how I smelled like urine and feces right alongside her to the end. I think about how she cried out, as if in labor, how the morphine I gave her helped cut the pain, but didn’t take it away, how I helped transition her out of the world, as she once transitioned me into it.

Before I left for the game, I opened a tube of her L’Occitane lavender hand lotion and rubbed it along my fingers and up my arms. I smelled Mother next to me. I said, “Now we both smell like death,” and I laughed out loud, even though it wasn’t funny. Her products wouldn’t stave off her decay, or my own inevitable death.

As I got ready for Dad’s volleyball game, I used Mother’s body wash, her shampoo, her conditioner, her blow dryer, her comb. I used her toner, her facial and body lotion, her sunscreen, foundation, face powder and the lightest mocha lipstick she had in her collection. I pictured her using each of the products, imagining her getting ready with me. Each application felt like a ritual, like I was embalming myself with a wordless love.

After the game, as I drove away from dad’s assisted living residence, I wondered what Mother would think of Linda and Bonnie and Betty, whether she’d be happy there were so many women there for Dad to tease, or whether she’d be embarrassed by his tone, his condescension or his cloaked desperation. But of course, that didn’t matter anymore. It didn’t even matter what she thought of me.

As I turned onto the freeway, I caught a whiff of Mother. I looked over my shoulder to see if she was there, but all I could see was my empty car seats. I veered into the far left lane and sped up, leaving behind Dad and his women and whatever would or wouldn’t happen between them, and leaving Mother behind too, certain she wouldn’t be accompanying me home, or anywhere, ever again. She’s lived her story. This next one is mine.

I so appreciate, Maureen, how you didn't tie everything up neatly with a bow. As if there is some point we can get to where the difficulties of who our parents are, or were, don't matter anymore. They always matter. At least they always matter to me. We just get on with things anyway, as you are. Thanks for this. ♥

Maureen: This touched me in so many ways-- moved me to anger, amusement, and empathy, even for that difficult father. I had an unusual but similar situation when my beloved Dad died at 56. In this case, typical gender roles were reversed. My mother was the all-commanding figure, my father the gentle (enabling) spouse. When my Dad dropped dead, she assured me that I needn't worry: she wouldn't cry at his funeral. The tacit message was, "You'd better not, either." Of course, I couldn't not cry. A ton.

I have long since forgiven my mom: gender discrimination had discouraged this brilliant lady early on, and booze had taken over early too. Thank you for your account!