Recently while watching Ripley on Netflix, I smiled when I heard the characters were going to stay at the Excelsior Hotel in Rome. Though I’d never stayed at the swank spot where Patricia Highsmith’s characters dwelled, I was once a frequent visitor at a different Excelsior Hotel, this one on the upper west side of Manhattan, where my godfather, Uncle Hans (Wolfgang Schwerin) lived for decades.

Located at 45 West 81st Street, the Excelsior stood across the street from the American Museum of Natural History. Whenever Mom took me to that building, where a giant whale hung from the ceiling, I knew that we might go see him.

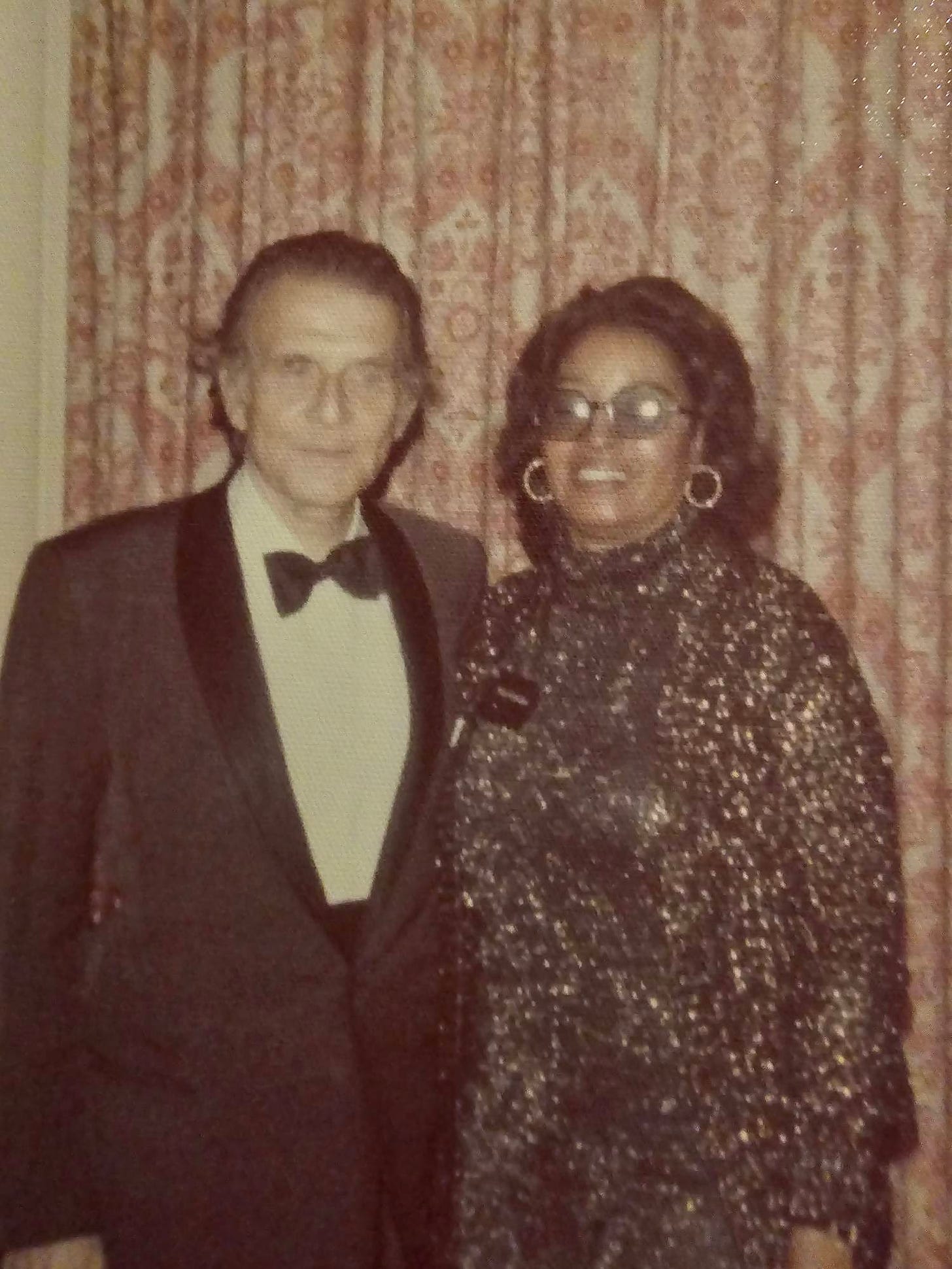

Always well dressed in expensive suits and polished shoes, Uncle Hans was about 5’8 with brown hair. He had met my mother Frances, whom he called Frankie, in the 1950s at a Harlem social event. Though he was a German Jew, he was cozy with many uptown Black folks, including writer Langston Hughes and more than a few of the social club butterflies who fluttered on the pages of Jet and the Amsterdam News.

In 1938, when Uncle Hans was 32, he and his family escaped Nazi Germany, fled to Switzerland, and then made their way to America. When escaping Europe Han’s family left much behind, including massive estates, possessions, and money, but they were still financially comfortable. Though he rarely talked about that side of his life, he’d endured much tragedy, and throughout his life pain renewed itself regularly.

I was once a frequent visitor at a different Excelsior Hotel, this one on the upper west side of Manhattan, where my godfather, Uncle Hans (Wolfgang Schwerin) lived for decades.

In June of 1966, three weeks before my third birthday, his mother, Stefanie Schwerin leapt to her death from a 10th floor window. “She used to babysit Mike Nichols when he was a kid,” Uncle Hans told me more than once. Three years later (December 28, 1969) his friend Bani Yelverton, a trailblazing Black model who crashed the colorline in fashion magazines, was supposed to make deviled eggs for his New Year’s Eve party ringing in 1970, but she didn’t make it. Days later, on January 6th, her slain body was found in the living-room of a Greenwich Village apartment where she’d been house-sitting.

***

In the ’60s and ’70s, back when I visited Uncle Hans most often, his building had a white awning with “Excelsior” emblazoned in gold. Through the revolving doors of the 16-story structure, in the lobby, there was a small coffee shop to the left. It was owned and operated by a petite Jewish woman named Sylvia who had a bubbly personality. Sometimes when mom and I stopped by, Uncle Hans brought us downstairs for apple pie or coconut cake with hot chocolate.

Though there was plenty of staff on hand, wearing white shirts and black pants, Sylvia always waited on us personally. She fawned over my chubby face and curly hair, admiring how much I’d grown since the last time she’d seen me. As I sat smiling in the booth, soaking in the admiration, Sylvia said, “He’s always the perfect little gentleman.”

Next to the cash register were neatly stacked boxes of Good & Plenty and Good & Fruity candies. Whenever Uncle Hans taxied uptown to Harlem to see us, he’d bring with him a couple of boxes of each for me. He usually celebrated Thanksgiving, Christmas, and sometimes Easter at our table, where he ate everything heartily, including soul food dishes like chitterlings and black-eyed peas. My grandma Mary did all the cooking, and it was so good, sometimes Uncle Hans took leftovers back to the hotel in never-to-be-returned Tupperware.

I found the scent of the Excelsior intoxicating. Though I’m not sure if it was the copper polish used in the elevator or the disinfectant used on the floors, I smelled it each time I was there. Uncle Hans lived on the 6th floor. In my mind, I can see myself walking with him; after exiting the lift, we’d turn left, walk to the end of the hall, and make another left.

Entering the apartment, it was hard not to be compelled by the art everywhere, beginning with the foyer. One of the pieces included a small canvas mom painted many years back, an impressionistic image of a roaring ocean. On the living-room wall was an oversized portrait of Uncle Hans’ grandfather, Dr. Paul Erhlich, the noted scientist who discovered the cure for syphilis.

When escaping Europe Han’s family left much behind, including massive estates, possessions, and money, but they were still financially comfortable. Though he rarely talked about that side of his life, he’d endured much tragedy, and throughout his life pain renewed itself regularly.

Opposite the windows was a floor to ceiling bookcase that held various books that he’d lend me years later including The ABC of Reading by Erza Pound and A Taste of Honey by Shelagh Delaney. The kitchen was tiny, but Uncle Hans never cooked anyway. I’d heard Mom scolding him about it. “You can’t eat Chicken Delight every night,” she’d say. Minutes after arriving, mom would be sitting on the couch, sipping from a glass of wine, as I looked out the living-room window onto the backyards of the private town houses on the next block.

When the weather was pleasant, there was always someone sitting behind the building reading, eating, entertaining, or lounging. Years later I described that backyard as “the kind of setting David Hockney might’ve painted, had he seen it.” Being a kid, I’d never heard the word voyeuristic, but I very much liked the godly sensation of watching people without being seen.

While I don’t remember when I started phoning Uncle Hans regularly, it might’ve been when I was in second grade and had few age-appropriate friends in school. One night I asked Mom, “Can I call Uncle Hans?” and it became a regular thing. More than fifty years later, I still remember the number: TR4-3503. Perhaps what I liked most was that he listened carefully and never spoke down to me.

Sometimes Uncle Hans talked about his daily five-mile jog in Central Park, or how his work was progressing. He was a writer, who worked from 9 AM to 6 PM every day. Years before he’d had a poem in Mass und Werte, a journal published and edited by Thomas Mann in 1940. I made sure not to phone him until after 6pm, when his work day was done.

“What are you writing?” I asked one evening. “Can I read it?”

“What I’m writing is in German,” Uncle Hans answered. “I’m afraid you won’t be able to read it unless it’s translated.”

I groaned. “Maybe you’ll teach me how to speak the language.”

Uncle Hans explained that the play he’d written dealt with mass hypnosis and mob mentality. I believe it was related to what he witnessed in Germany when the Nazis came into power. I could imagine him sitting at the cluttered desk in the bedroom that held the telephone, a typewriter, pens of various colors, a small pipe rack, and a homemade caddy for his many eyeglasses. I loved his spectacles so much that I attempted to fail the school eye exam so that I too could wear them.

When I was 8, it was at that desk where Uncle Hans began teaching me to be a writer. One afternoon while visiting the Excelsior with my mother, Uncle Hans asked, “Would you like to dictate a story to me? I’ll type it as you talk.”

Earlier that afternoon Mom had taken me to the movies to see The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight, a goofy mafia flick based on a novel by Jimmy Breslin. When I finally started talking out my story to Uncle Hans, it included elements I’d seen in on the screen, including Brooklyn gangsters, caged lions in the basement, and exploding cars combined with my own fantastical musings.

Uncle Hans typed the story on nice paper, using a typewriter that had large letters, necessary since he had terrible eyesight. Over the years I’ve written all types of material, but crime narratives remain a favorite genre. To this day I have no idea what prompted Hans to guide me towards writing, but I’m obviously pleased that he did. A few months after that first short story he bought me a teal Olivetti typewriter and with one finger I began typing short stories, poems, and comic book scripts inspired by The Twilight Zone, The Outer Limits and Saturday night sci-fi/monster movies on Creature Feature or Chiller Theater.

Entering the apartment, it was hard not to be compelled by the art everywhere, beginning with the foyer. One of the pieces included a small canvas mom painted many years back, an impressionistic image of a roaring ocean. On the living-room wall was an oversized portrait of Uncle Hans’ grandfather, Dr. Paul Erhlich, the noted scientist.

Sometimes I’d read my latest piece to him over the phone. “How do you know when a story is finished?” I asked one night. Uncle Hans chuckled. “Well, if you judge by the stories in the New Yorker, you can end a story at anytime,” he replied. “I don’t think there is just one rule. As the writer, you’ll know when it’s ready.” Decades later, when watching the film Finding Forrester (2000), I was reminded of my godfather.

Thankfully, unlike the cranky Sean Connery character, Uncle Hans wasn’t bad-tempered or a recluse. Twice a year he travelled, visiting his brother Günther in Germany, or relaxing at a Catskills resort known as the Beaver Lake House in Krumville, N.Y. His letters were always detailed accounts of his trip, complete with primitive pictures he drew of himself on a ski slope or in a speeding car racing across the Autobahn.

In the fall, when he would go to the Beaver Lake House, his pictures would be full of squirrels, deer and other woodland creatures. I rode up to the Beaver Lake House on the Greyhound with my mother a few times. The road was dark, spooky and deserted. The resort was owned by a German-Jewish couple, and most of the guests were of the same origin. It wasn’t like the place in Dirty Dancing, filled with families looking to be entertained, but rather it catered to an older, more intellectual crowd. Artist Marc Chagall stayed there for six months in 1945, after his wife Bella died.

There were private bungalows as well as a three-story main inn with guest rooms. Usually the only other child there was Colette, the chef’s daughter, who soon became my best friend for the duration of the short trip. A cute child with blonde hair and a tomboy streak, she reminded me of Eloise. But instead of roaming through the Plaza, we played in the kitchen where her father, Lucian, worked. Other times we went outside where it was always chilly, and sometimes popped into Uncle Hans’ bungalow, where there was always candy. One year my mom bought me a kaleidoscope that he and Colette never tired of; once there was an afternoon cocktail party and Colette and I got dressed-up and sipped ginger ales as though they were highballs. We were both 6 years old. A decade passed before we saw each other again.

1979 was the year I stayed overnight at the Excelsior Hotel, when Uncle Hans and I went to the Beaver Lake House together. At 16 I crashed on the couch beneath the massive Paul Ehrlich painting, a man I knew little about; I’d often tried to stay awake through The Magic Bullet (a movie with Edward G. Robinson portraying the Nobel Prize winning scientist) on the late-show, but always fell asleep minutes into the film.

When I was 8, it was at that desk where Uncle Hans began teaching me to be a writer. One afternoon while visiting the Excelsior with my mother, Uncle Hans asked, “Would you like to dictate a story to me? I’ll type it as you talk.”

The following morning I was up early. Uncle Hans had ordered a limousine to take us to Krumville, and I took our luggage downstairs. As I was placing the bags in the trunk, the white limo driver standing to the right of me, said, “That’s very nice of you.” Puzzled, I asked, “What are you talking about? What’s nice?” The driver shrugged his shoulders. “I mean, aren’t the maintenance men and building superintendents on strike.”

I icily stared at him for a moment and then laughed heartily. The driver assumed because I was Black that I worked for the hotel. “I’m neither. I’m going on this trip. You’ll be driving me and my godfather.” Dude turned red and got back inside the car. Throughout the two-hour ride, every few minutes I noticed him glancing back at me in the rearview mirror.

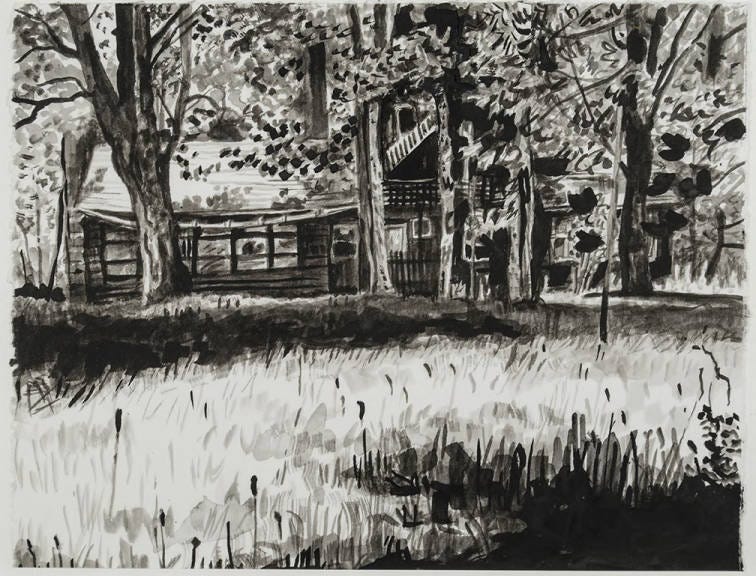

In the early ‘80s the Beaver Lake House was sold. Like many of the old-school Catskills resorts, it’s now a rural ruin. In 2013 artist Amy Talluto captured the lost beauty of the property in a series of six pen and wash drawings.

***

After graduating high school in 1981, I began attending Long Island University, Brooklyn campus, where I majored in English. That fall I also sold a fantasy short story (“Fading Memories”) to comic book magazine Darkstorm. Uncle Hans took me out to dinner to celebrate. The restaurant was on Columbus Avenue, a few blocks from the Excelsior. The neighborhood in the early phases of being gentrified, a process that changed the community drastically throughout the decade.

The following year Uncle Hans’ play VORSTELLUNG in drei Akten was published in Germany. During that period, having gotten busy with school, a new girlfriend, writing for the campus newspaper and the long commute to Flatbush Avenue every day, I called Hans less often.

The last time I visited Uncle Hans was in early 1987, when I had to share time with a German film crew making a documentary about Paul Erhlich. Though I still couldn’t speak German, I imagined Uncle Hans was telling the journalist about playing in his grandfather’s lab, or sitting on the old man’s lap as the bearded doctor puffed his pipe.

Two months later I received a letter from a midtown law office telling me that Uncle Hans had died and left me a bit of money. At 81, he was suddenly gone. It felt surreal. I rushed downtown to the Excelsior, but was informed that the apartment had been cleaned out weeks before. I thought about Hans sitting at his desk working, hunched over his typewriter, or talking to me on the phone. Next to the desk was a color TV, but Uncle Hans claimed he only watched on Sunday nights, to see 60 Minutes, or when there was something interesting on PBS. One night he’d seen Truman Capote being interviewed on the Dick Cavett Show, and the following evening told me how much he hated that man’s voice.

The front desk wasn’t very helpful, claiming to not even know the cause of death. Standing there helpless, I felt as though I was on the rollercoaster at Rye Playland plunging downward. Walking across the lobby I laughed when I remembered the time, back when I was a kid, asking Uncle Hans, “Can you explain Einstein's theory of relativity?”

“It’s a lot more complex than you think,” he replied.

Two months later I received a letter from a midtown law office telling me that Uncle Hans had died and left me a bit of money. At 81, he was suddenly gone. It felt surreal. I rushed downtown to the Excelsior, but was informed that the apartment had been cleaned out weeks before. I thought about Hans sitting at his desk working, hunched over his typewriter, or talking to me on the phone.

Of course, so is life. I felt guilty, as though I were the Prodigal Godson; I hadn’t meant to get too busy to call or visit, but still I felt terrible about not making time. More than 30 years later I think about Uncle Hans often, wishing I could’ve shared with him my first book sale, tales about working on the staff of several magazines and, most recently, my mission to bring back to literary life several out-of-print Black authors by writing essays about their work.

Indeed, none of that would’ve been possible if it weren’t for him. As Mom has said often, “When I taught you how to read and Hans taught you how to write, we created a monster.” As for the hotel, it has been through many changes, but has been given Landmark status. According to newspaper reports it was sold in 2021 for $80 million and the new owners are turning it into an ultra-lux residential rental residence.

I haven’t been inside that building since that day in 1987 when I stood by the front desk, took a deep breath and stored that special smell somewhere in my brain. Minutes later I walked outside, stood in front of the building and silently said goodbye to the Excelsior Hotel and Uncle Hans.

Thank you for this tender reminiscence founded in mutual respect, appreciation and love despite vast differences in age and other obvious mentionables.

Just yesterday, a friend and I sat on a bench opposite what was once The Excelsior, just watching people go by. How much richer that experience would have been had we read your piece beforehand. And sadly, how prescient Uncle Hans was in writing a play about mass hypnosis. But he is in you and now we know that.

I hope most of you see this. Thank you so much for your kind words concerning "Godfather's Hotel." I feel very blessed and thankful. What more can an old writer ask for? 💝