Full Body Scan

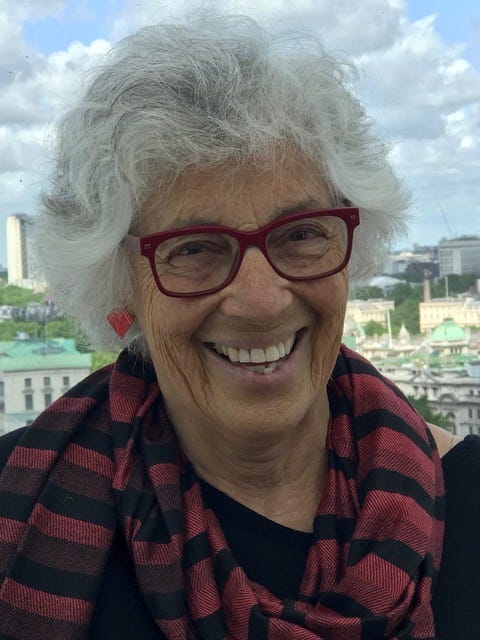

In an excerpt from her essay collection, "The Kitchen is Closed: And Other Benefits of Being Old," Sandra Butler assesses her 83-year-old body from head to toe.

As I drove down the freeway, my radio program was interrupted by an enthusiastic young man suggesting products I might buy to overcome the ravages of the aging process. Really? I thought. Am I ravaged? Ravaged sounded permanent. Like a building that has already collapsed.

When I arrived home, I removed my coat and shoes, then my bra (we’ll get to that later) and readied myself for a full body scan to assess my ravages. Pulling off my socks, I focused on a nearly 40-year-old bunion (a direct consequence of the requisite pointed toe shoe designs of my pre-feminist young adulthood) covered with a day-old curling bunion pad and started the process at ground level.

My feet are decidedly flat. When I was 8 years old, my nervous mother took me to a chiropodist who determined that I needed steel arch supports placed inside my Buster Brown oxfords. They didn’t work, my arches never rose, and he later became my piano teacher, but that’s another story. My toenails are currently a bright red because five of my old woman friends and I just came back from a vacation/celebration of our 30-year friendship and knowing I would be wearing a bathing suit in public I decided to paint the parts of my body that still lent themselves to decorative enhancement.

Really? I thought. Am I ravaged? Ravaged sounded permanent. Like a building that has already collapsed. When I arrived home, I removed my coat and shoes, then my bra (we’ll get to that later) and readied myself for a full body scan to assess my ravages.

Moving northward, I arrive at two silvery scars, one over each knee, announcing the placement of titanium where there once was bone. I could have paused to mention puffy ankles from middle-aged falls that I never bothered to treat. I just elevated, iced and forgot about them. I still do. My ankles are fine. Strangers pat my knees every time I go through airport screening, but they work remarkably well. The pain of the surgery has dimmed just as my surgeon—who had a blindingly toothy male smile—assured me it would: “It’s like childbirth.” How the fuck do you know what childbirth is like? I thought. But he was going to be re-designing my body with complex carpentry and I was going to be unconscious. It didn’t seem the moment for feminist education. I’m still angry at myself for not letting him know it wasn’t an appropriate parallel.

Then there are my thighs, puffy like my ankles. I have hated them since I was a teenager. Of course, they were probably lovely 68 years ago but in those critical years, when the desire for bodily perfection, or at least the perfection I imagined Judy Hirschman represented was an obsession, I was certain that my thighs were all wrong and too thick because their insides rubbed together when I walked. I didn’t want them to touch but no matter what I did, including wearing a girdle for a painful year, they continued to touch and continue to make insistent and ongoing daily contact.

Right at the juncture of those unsatisfying thighs is my pudenda, now oddly girlish, exposed and with dandelion-like puffs of grey, all that remains of my once full, dark, and curly pubic hair.

Moving around to my buttocks which are heeding the inevitable call of gravity and inching ever southward, I come upon folds and creases, like a rippling origami of my skin, a general softening. Viewed through a more astrophysical lens, my behind resembles the pockmarked surface of the moon.

I was certain that my thighs were all wrong and too thick because their insides rubbed together when I walked. I didn’t want them to touch but no matter what I did, including wearing a girdle for a painful year, they continued to touch and continue to make insistent and ongoing daily contact.

Then there is my stomach. It has done herculean (Megaranic? She was Herc’s first wife) service over my lifetime. Both my now middle-aged daughters got their start in there. It was a home, a sanctuary, a hatchery. Now it’s a fallen soufflé.

My breasts have always been large and over the decades become increasingly pendulous, requiring a bra with a sturdy wire to hold them still. I had a period of bra experimentation during my sixties, searching to find just enough wire to hold me up with just enough elastic to keep everything in place, and my second drawer (the first is for underpants and the third for socks) is filled with an assortment of my efforts to find the right band, size and shape. As a result, I have no bras that fit me comfortably in all ways, but some are better for sweaters, others for exercise, others for when I want to feel cute. I have lace, cotton, solids, patterns, and they all work to hold my breasts somewhere north of my stomach.

When I arrive home at the end of my day, the third thing I do, after removing my coat and shoes, is to unhook my bra. The comfort of releasing my breasts from their day-long bondage and feeling them rest upon my chest and move around when I do, is a great release and freedom, although not a freedom I am prepared to impose on the outside world.

I feel tenderly toward my breasts. I loved a woman who had cancer and had one breast removed and I know how much she missed it/her (we had named them) until she died three years later. I’m grateful to have been able to keep my own shapeless bundles.

The pain of the surgery has dimmed just as my surgeon—who had a blindingly toothy male smile—assured me it would: “It’s like childbirth.” How the fuck do you know what childbirth is like? I thought.

My arms are currently decorated in deep purple splotches which is the combined result of having thin skin (both physically and emotionally) that bruises at the slightest provocation, as well as the side effect of a medication (one of many) I am taking for rheumatoid arthritis.

The bruises begin with small, randomly patterned rose-colored spots (petechiae) that mysteriously expand, assuming amoeba-like designs on my arms, becoming a glowing deep purple, eventually fading, only to reform with small spots in another location. Like a light show.

The skin of my underarms waves like seaweed when I move. My fingernails split and crack easily. I’ve rubbed Vitamin E into them every day for fifteen years, which so far does not appear to have slowed the tempo of their decline but has left Vitamin E stains on many of my sleep tee shirts.

Moving northward I come to my neck, which compared to some necks, is actually pretty OK. No wattles. No deep jowls. Just an ordinary 83-year-old’s number of wrinkles. I have a neighbor who had a face lift, which left her face as smooth as a baby’s behind but connected to an old woman’s crinkly neck.

I feel tenderly toward my breasts. I loved a woman who had cancer and had one breast removed and I know how much she missed it/her (we had named them) until she died three years later. I’m grateful to have been able to keep my own shapeless bundles.

We arrive at my face which, during the past 20 years has sprouted deep grooves, apparently while I slept, like tributaries that ought to lead to some central channel, but instead meander across my cheeks, around my eyes and mouth. A face full of channels, leading nowhere. Liver spots of a variety of sizes and shades mark the spaces between.

Once, my middle-aged daughters, who were in the process of figuring out their own middle-agedness and not entirely comfortable being confronted with such an old mother, took me to Sephora where we all bought products, leaving with a bag stuffed full of brushes, emollients, and creams designed to put an abrupt and permanent end to aging. I made one failed effort at exfoliating, plucking, moisturizing, concealing and blushing. My tributaries and liver spots remained, but my skin looked glittery, like I was perspiring in a different color. Still, I can’t bring myself to throw all the stuff out, and the remains of my efforts are in a plastic bag under my bathroom sink next to the economy-size bag of cough drops.

My teeth appear to be holding on, although when I smile broadly, which I often do, one has a bird’s eye view of the archeology of my dental life. The white part of my smile is in the front. Moving to the sides and back one sees a repository of old silver fillings, aging gold crowns, and a bridge that is increasingly wobbly. But the front, except for one tooth that appears to be sliding sideways, has the help of whitening strips I use every few months. The theory is that being blinded by the whiteness of the front of my mouth will keep eyes averted from the silver and gold glistening from within its recesses.

After repeated and unsuccessful efforts at encouraging me to see an audiologist which I repeatedly and determinedly assured her I didn’t need to do, she whispered to me in the month before her death, “But honey, what if on my death bed I want to say a deeply important thing to you, and you don’t hear me?”

My ears are plugged with aids without which I can only smile warmly, read the lips of the speaker and try to respond in a way that has some relationship to what is said. I began wearing hearing aids nearly half a lifetime ago when my love was dying. After repeated and unsuccessful efforts at encouraging me to see an audiologist which I repeatedly and determinedly assured her I didn’t need to do, she whispered to me in the month before her death, “But honey, what if on my death bed I want to say a deeply important thing to you, and you don’t hear me?”

That did it. I had a hearing aid exam the very next day not wanting to miss her death bed wisdom. (But even as my ear was filled and poised to receive her words, at the moment of her death she didn’t say anything, just smiled at me.) I began with one “skin-colored” peanut-size apparatus, deciding to start with only one ugly appliance at a time. But while driving home I heard the sound of a fire engine approaching and couldn’t tell whether it was behind me or approaching from the side. I relented and purchased the second one. Over the years they have become smaller and more accurate, an automatic part of my moving into the day.

My eyes have been covered by glasses since before I entered middle age but now, I try to purchase stylish and colorful designs, given that there is little remaining style or color in my face. Just those tributaries and liver spots. For the past ten years, my glasses have been a bright red. I wear earrings to add something decorative to my face, although in truth, when I’m having a conversation with someone, I actually want them to be looking at my face, not my ears.

Ah, but then there is my hair. I have glorious gray, thick, wavy hair. There is the inevitable thinning spot at the crown—everyone has that my hairdresser reassuringly tells me—but my hair has been a source of pride since my ponytail days, and on through the pixie, the bouffant, the butch spikes, the long, and the arranged to appear not arranged, stylish, I think and quite beautiful.

Radical feminist hectorers understood the ubiquitousness of the male gaze and how all of us saw our bodies as never enough, too big, too small, too thick, too thin, wrong in every possible way. Always wrong.

When I was in my 40s, my life centered around what my mother resignedly called “rabble-rousing,” and what my daughter called, when her teacher asked her what her mother did, “hectoring people.” I was a rabble-rousing hectorer. I suggested to women that they go into their bedrooms, lock the door so they are assured they are alone, remove all their clothes and stand in front of the mirror. Then, I would add, “see whose eyes you are looking through when you look at yourself. Are they your own or are they male eyes?”’ Radical feminist hectorers understood the ubiquitousness of the male gaze and how all of us saw our bodies as never enough, too big, too small, too thick, too thin, wrong in every possible way. Always wrong.

I practiced my own exercise then and looked at my 45-year-old body with delight. I was sexual, I was strong, I was intact and healthy. I was certain that the eyes through which I was looking were my own. Except of course for the thighs. I skipped over them.

Now I repeat my own exercise, seeing the fleshy consequences of 83 years, all that I have asked of this increasingly exhausted vessel, all it has allowed me to do. Now my skin is old, softening, dry, wrinkled and tired. I gently rub lotion over it with love.

Thank you! And yes our hair thins. Our bones thin. Everything thins, except perhaps our stomachs and hips which tend to go in another direction.

Oh, Sandy, what a wonderful piece to come across! The bra story is one that made me laugh! As soon as I got in the car after work, the first thing I did was unhook it! And still some days after all the running around, it’s such a joy to feel that release. Love you! Paula Shara Freedman