For the Love of Dionne

A new documentary and an art exhibit put 80-year-old Dionne Warwick back in the spotlight. But as far as journalist and critic Michael A. Gonzales is concerned, she never left it.

During a pivotal scene in The Many Saints of Newark—the prequel to The Sopranos that takes place in the ’60s—“Anyone Who Had a Heart,” a Dionne Warwick single from 1964, comes on the radio, prompting prospective beautician Giuseppina Moltisanti to muse aloud, “I wonder where she gets her hair done?”

The reference is a reminder that Warwick was a fixture on the airwaves back then. Who could have guessed, in those days, that so many years later, at 80, she’d become super-relevant again?

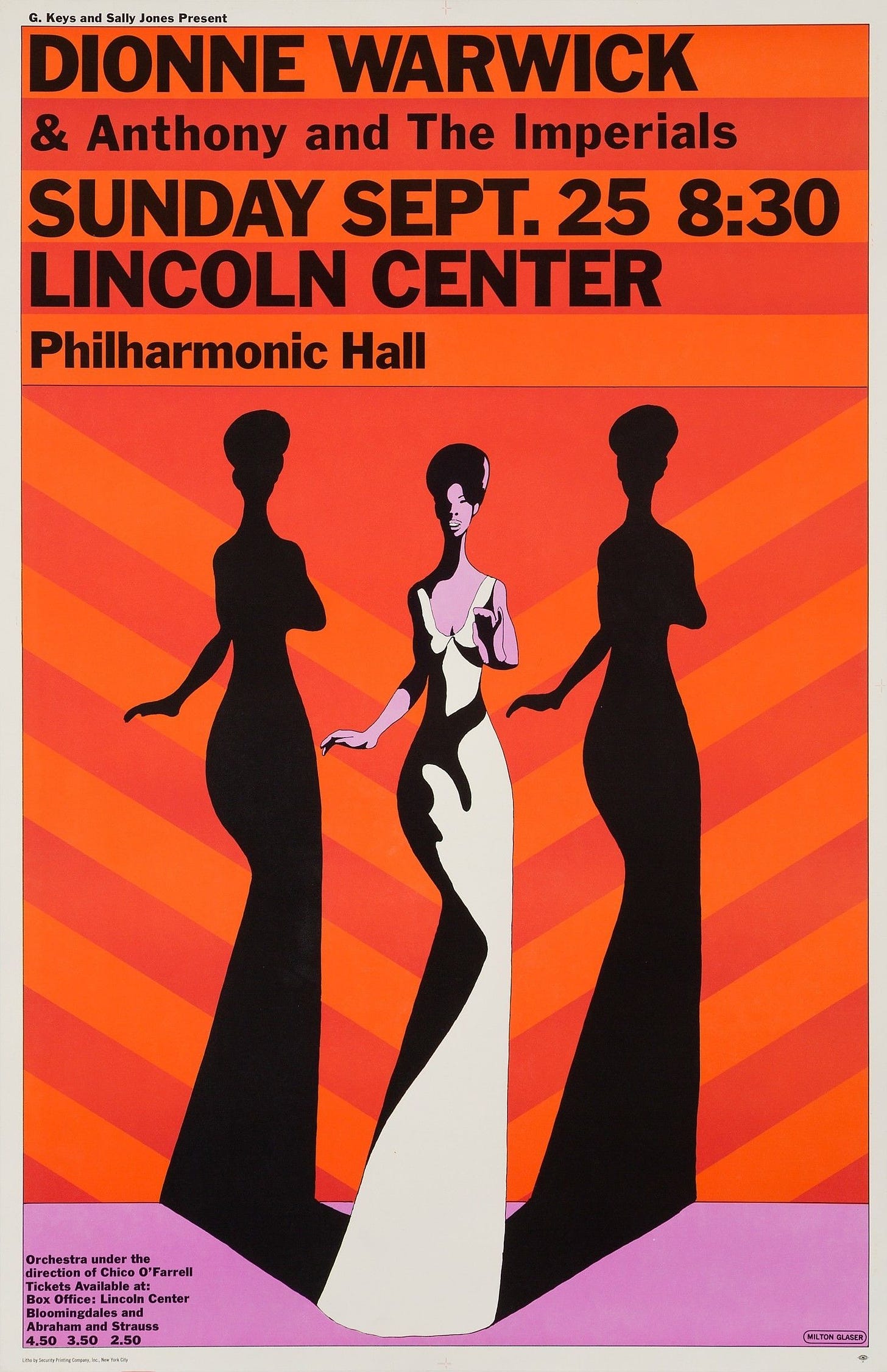

Warwick is having a moment right now, taking up some much-deserved real estate in the pop-culture landscape. She’s the subject of a new documentary, Dionne Warwick: Don’t Make Me Over, which premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival, and of an art exhibit, Dionne Warwick: Queen of Twitter (at Hahne & Co., 609 Broad Street, Newark, NJ)—an homage to her entertaining Twitter account—featuring a collective of artists assembled by curator Souleo, opening today, October 6th, and running until the 29th.

But for many—including me—Warwick has never for a second been not relevant, just a voice on an oldies station. She has always been a regular fixture on my own personal airwave, and probably always will be.

Autumn has always been one of my favorite seasons. It’s the time of year that always brings me to reflect back on those golden years of my uptown Manhattan childhood in the late-’60s/early-’70s, when fall represented bright red candy apples, new television programs and cartoons, changing leaves on Riverside Drive, and getting used to a new grade and teacher. After spending the summer in Pittsburgh, riding bikes and hiking through the woods, I’d return to the ritual of waking-up at 7am, the smell of grandma’s Maxwell House lingering in the morning air as mom struggled to get me and baby brother ready for the day.

Warwick is having a moment right now, taking up some much-deserved real estate in the pop-culture landscape.

Our apartment wasn’t very big, and every morning, before walking down the hall to the room I shared with baby bro, mom switched on the boxy brown radio on the living room end table. Tuned to WNEW-AM, the light music played as I stood on the white tiled bathroom floor getting washed. WNEW was known for its dedication to the “American Songbook,” and classic pop singers like Sara Vaughn, Nat King Cole, Peggy Lee and the king of the pack, Frank Sinatra, were hailed and spun as often as possible. It was through WNEW that I was introduced to the “Make Believe Ballroom” hour, featuring the music of Cole Porter, the Gershwin Brothers and Sammy Cahn.

However, by the time I was headed to pre-K at the Modern School in 1969, the station modernized its morning drive-time sounds and began mixing in the music made by a new generation of “swinging sixties” stars that included Tom Jones, Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass, Shirley Bassey and Warwick—a singer whose emotionally evocative singles have travelled with me from childhood to middle-age, songs I still listen to regularly.

For me, Warwick fandom was never just about sound, but also meaning. She had a knack for choosing songs that were more emotionally complicated than they might have seemed at first listen. Numbers like “Anyone Who Had a Heart,” and many of Warwick’s other hits, cast a spell of romance, despite being about an “untrue” partner who continues to hurt and desert her. Few of Warwick’s songs from that period were genuine ballads, but actually anti-love songs that sometimes spilled over to a breakdown (“Walk on By”) or stalking (“Are You There (With Another Girl”). These songs were pure blues disguised as sugary pop.

They were written and produced by Burt Bacharach and lyricist Hal David, the most consistent hitmakers of their generation—Brill Building veterans. Their music and lyrics were dramatic, complex and addictive. While the duo worked with many talented singers, Warwick was their true muse, the performer who transformed words and notes on the page into something real that millions of listeners gravitated towards.

As I’ve grown older, many childhood memories have faded in the fog of age, but one that remains still clear is the experience of falling hard for the anti-love anthem “I'll Never Fall in Love Again,” after hearing it more than a few times on WNEW. Since I was usually a shy, reserved kid, it must’ve been amusing when one morning I suddenly burst into song before breakfast, having learned Warwick’s lyrics and phrasing from joyful repetition. “What do you get when you fall in love? You only get lots of pain and sorrow,” I belted, sounding more like Alvin and the Chipmunks than a broken-hearted romantic soul chanteuse.

For many—including me—Warwick has never for a second been not relevant, just a voice on an oldies station. She has always been a regular fixture on my own personal airwave, and probably always will be.

Of course, at that age I knew nothing of love, first kisses, or brokenhearted sweethearts, but there was something about Warwick’s voice that appealed to the future writer I would become, both romantic and melancholy.

Bacharach once referred to their material as “mini-movies.” Undeniably, a film version of “Anyone Who Has a Heart,” directed by Mike Nichols, or Blake Edwards’ interpretation of “Do You Know the Way to San Jose,” would’ve been fun. But the cool cinematic texture of their songs, conjured in my mind by Bacharach’s lush arrangements and orchestrations, David’s intricate lyricism, and Warwick’s emotional vocal styling, was enough for me.

Although that era of Black pop was dominated by wailers like Queen Aretha and twisted sista Tina Turner, WNEW tended to more often play the more reserved songs of The 5th Dimension, featuring the aural wonderfulness of Marilyn McCoo, and Warwick. Though their vocals were lighter by comparison, I’d argue against anyone who denied their soulfulness. In reality, soul music isn’t just about how high your singing can soar, but the way your voice makes people feel.

Still, if Warwick—who was born into a gospel wailing family in East Orange, New Jersey—had wanted to go that route, she had it in her. As a child she sang in church and often shared a microphone with her aunt, Cissy Houston, a legendary background singer (Wilson Pickett, Elvis Presley) and the mother of Whitney.

“Gospel was my first love and it was the first music I learned to sing,” Warwick told Newark Bound magazine in 2017. “We used to sing ‘Jesus Loves Me’ in Sunday school, but one day at the regular service, my grandfather, who was the minister, called me to the pulpit to sing. I was six years old, so he stood me on some boxes so people could see me.”

On Sunday nights, Ed Sullivan came on, and I recall sitting in front of the black and white set staring at the screen as Warwick’s gown sparkled beneath the lights, and her beehive doo towered towards heaven, as she swayed slightly in her heels.

As a teenager, Warwick started the group the Gospelaires with her sister Dee Dee, Myrna Utley and Carol Slade. Discovered at the Apollo after she and the group performed at a review, Warwick was recruited to sing back-up for Newark’s own Savoy Records jazz man Sam “The Man” Taylor. In her 2010 autobiography, My Life, as I See It, she wrote: “As a result of that first date, the Gospelaires fast became the female voices of choice for background work in New York. We worked behind some of the biggest recording artists of that time: the Shirelles, Ray Charles, Dinah Washington, Ben E. King, Chuck Jackson, the Exciters, Tommy Hunt, Solomon Burke, and the Drifters, just to name a few. So at age seventeen, while in my senior year preparing to graduate from East Orange High School, my career had begun.”

It was after songwriter Bacharach heard her singing background on the Drifters’ “Mexican Divorce,” a track he co-wrote, that he recruited Warwick to sing on demos that he and then-new writing partner Hal David composed. It didn’t take long to record her first single, “Don’t Make Me Over,” in 1962. Half-a-year later, in February, 1963 (four months before I was born), she released her debut album, Presenting Dionne Warwick on Scepter Records. The disc featured her first hits with Bacharach and David, including the upbeat musically, but depressing lyrically, “This Empty Place,” and “Make It Easy on Yourself.”

Without a doubt, that was the just beginning of Warwick’s string of hits with that dynamic duo, as well as a start of a long career that included appearances on The Ed Sullivan Show, television specials, major tours across the world, and nominations for numerous Grammys, beginning in 1964 with “Walk on By.” Later, other artists including Dusty Springfield, The Walker Brothers, The Carpenters and Ron Isley recorded the same material, but, for me, Warwick brought a special quality to those songs that was hard to match. However, two covers that I do cherish are Isaac Hayes’ soulful epic “Walk On By” and Luther Vandross’ romantic calamity “A House is Not a Home.”

Vandross was a student of Warwick’s from the time he was a boy, studying both her records and live shows at the Apollo. In 2001 when I profiled Luther for Savoy magazine, I had the pleasure of interviewing Warwick as a secondary source. In our interview, she said that Vandross’ cover of “House…” was, “…the definitive version. Any song of mine that Luther covered always preserved the integrity of the song.” Later in our conversation I mentioned that it pained me that so few people talked about lyricist Hal David’s work, usually referring to the compositions solely as Bacharach songs.

“Well, you know what I tell people?” Warwick asked cheerfully. “I tell ’em, if it wasn’t for Hal, you would just be humming.” While she talked, I imagined her looking like she had the times when I’d seen her on television years back, when there were only three major networks and Black folks being on any of them was an occasion for celebration.

At home, we watched our share of variety shows and tacky music specials. On Sunday nights, Ed Sullivan came on, and I recall sitting in front of the black and white set staring at the screen as Warwick’s gown sparkled beneath the lights, and her beehive doo towered towards heaven, as she swayed slightly in her heels. With a world-weary elegance in her voice, she always looked so fancy singing those songs. However, as Warwick had been saying for years on those tracks, nothing beautiful lasts forever; in 1973, she parted company with Bacharach and David , their last collaboration being Dionne in 1972.

The break occurred after the release and failure of Lost Horizon, a musical remake of a 1937 film, for which Bacharach and David had written the soundtrack. They’d worked on it for two years. The film was a critical and box office failure, which caused a rift between the partners that led to their break. According to Billboard, “Bacharach became so depressed he sequestered himself in his vacation home and refused to work. Bacharach and David sued each other and Warwick sued them both [for abandoning her, creatively]. The cases were settled out of court in 1979 and the three went their separate ways.” The trio reconciled in 1992 on Warwick's "Sunny Weather Lover," but the song was lackluster in comparison to their past pop brilliance.

Her Bacharach/David songs were more than a soundtrack; they became a part of me, having worked their way into my DNA.

Though many might’ve expected for Warwick to disappear into the desert of Las Vegas doing two shows a day, she has instead continued recording and remained relevant. There were highs and lows over the years, including her involvement with the shady Psychic Friends Network, but as an artist and a pop interpreter behind the microphone, Warwick has never disappointed.

Over the decades, no matter what type of music I was into (heavy metal, glam, hip-hop, free jazz) there was always a copy of Warwick’s hits nearby, in whatever format I was listening to at the time—vinyl record, cassette, or CD. Her Bacharach/David songs were more than a soundtrack; they became a part of me, having worked their way into my DNA. From budding romances to near marriages to eventual heartbreak , Warwick was always there, singing in my ear.

A few of my darlings include the weepy protest song “The Windows of the World,” a social consciousness rarity in her canon, “Trains and Boats and Planes,” and “Message to Michael.” After playing that last song for my ex-girlfriend Val years back, she said, “That’s not fair. Now every time I hear a Dionne Warwick song I’m going to think about you.” Truthfully, I can’t think of any better sixties pop songs to be associated with.

Pop culture junkie Michael A. Gonzales writes for CrimeReads, LongReads, Soulhead.com, Cuepoint, Catapult, and The Wire UK.

Ah! Michael writing about Dionne is the treat I needed!