Ecstasy for Easter

"Changing our minds in one afternoon." PLUS: A Friday Open Thread on our experiences with MDMA and other psychedelics...

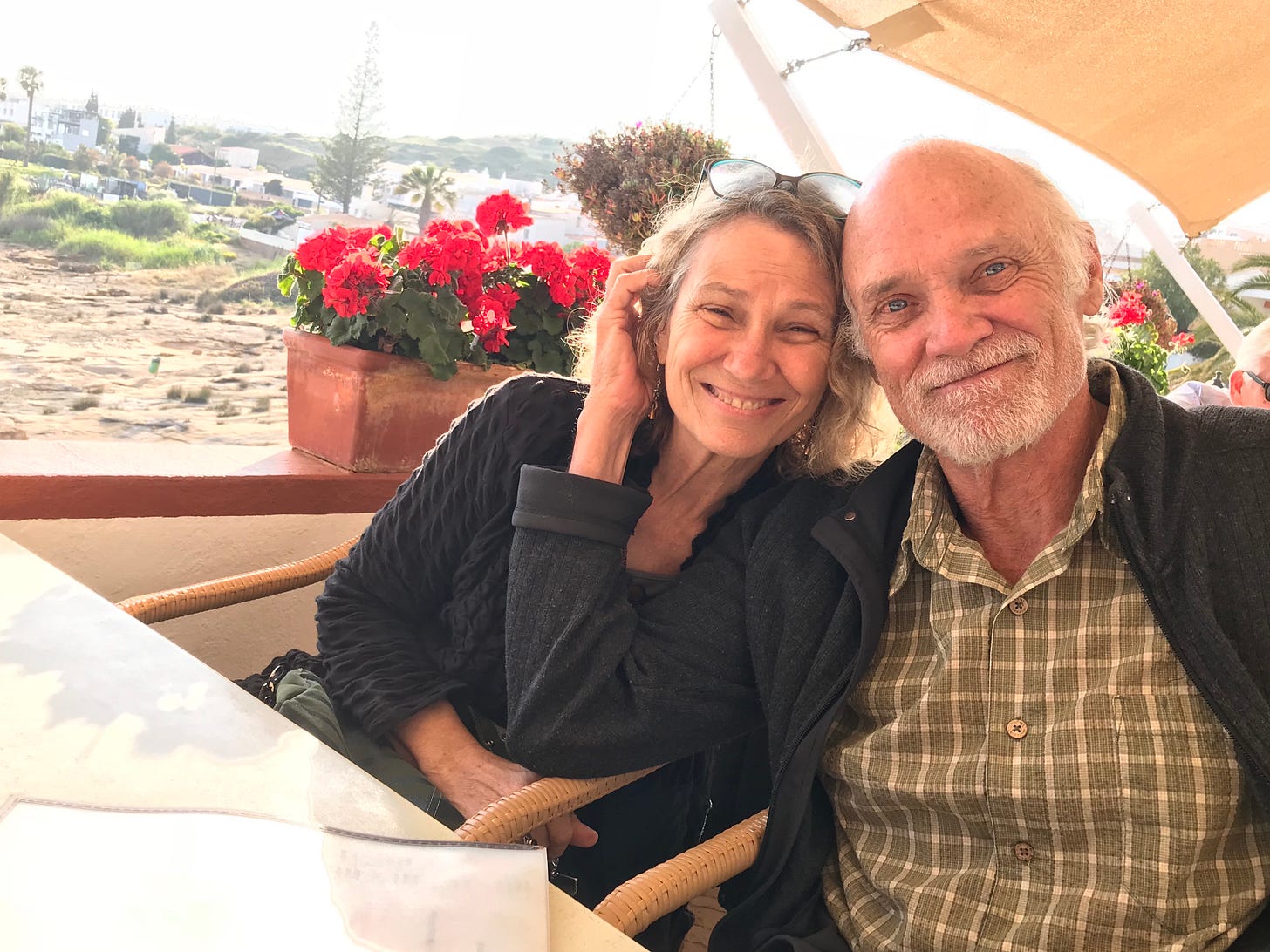

Readers, today we have an essay from Kristin Ohlson about an experience she had taking methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), a psychedelic drug also known as “Molly” and “Ecstasy” with her partner, Tim. The piece is down below this section. ⬇️

I know a lot of people who take psychedelic drugs recreationally, for fun, or relaxation, or mood enhancement, to good effect. I’m also fascinated with the new research around psychedelic drugs, and how they’re being used clinically to help people with depression, PTSD, and other psychological issues. I really enjoyed Michael Pollan’s documentary, How to Change Your Mind, an off-shoot of his book with the same title. (A woman who took a writing workshop of mine is featured in the MDMA/Ecstasy part.)

I thought this would make a good Friday Open Thread subject to have all of you weigh in on, too. In the comments, please tell us:

How old are you? Have you taken Ecstasy, or other psychedelic drugs? Did you take them recreationally? What were the circumstances? Did you take them medicinally, under the guidance of a physician or other clinician? Was your experience with psychedelics positive? Negative? Neutral? Would you do them again? (If you’re commenting, please also do me the favor of hitting the heart button ❤️ for algorithmic purposes. Thank you!)

Me, I’m 59. I’ve never tried Ecstasy, but I did one psychedelic mushroom trip ten years ago with my husband, Brian. We accidentally took a heroic dose, which left me intermittently laughing and crying (and laughing and crying) very loudly in a public park. Luckily for me, Brian had a fairly hippie-ish adolescence and young adulthood, and has a lot of experience with mushrooms, LSD, and other psychedelics. He was able to override the effects of his trip and act as my guide.

It was a challenging but ultimately positive experience that opened my mind and gave me perspective on some difficult things I’d been wrestling with. It was also pretty mind-blowing to perceive the grass and the leaves on the trees as growing mouths, and talking to me. I was very self-conscious the whole time, and kept asking Brian whether the things I was thinking and feeling while on mushrooms were “a cliche.” 😂

One time a few years before that, someone blew some dimethyltryptamine (DMT) smoke in my mouth, and the shapes and colors of everything in the room changed for about five minutes, and also, tiny little Maurice Sendak-y monsters—friendly, dancing ones—appeared at the edges of my vision. (DMT is a component of ayahuasca, which is used as ceremonial medicine in South America and elsewhere. I really enjoyed this essay by The Real Sarah Miller about an ayahuasca journey she went on in Peru.)

A couple of winters ago, when I went through a difficult depression, I considered trying ketamine therapy. Ultimately, after hearing a mix of positive and negative reports from friends, I chose not to. (I really enjoyed this essay by my friend Janet Steen about her experience with Ketamine therapy.)

These days I take a quarter or half of a mushroom gummy a couple times a day, and I think it lifts my mood…? I’m also very susceptible to the placebo effect, so that could account for what I’m feeling. I also nibble small portions of gummies infused with tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the psychoactive component of cannabis, during the day, and ones with THC and CBN to help me sleep at night.

Here’s Kristin Ohlson’s essay. ⬇️

Ecstasy for Easter

Changing our minds in one afternoon.

By Kristin Ohlson

The day before Easter, I phoned my daughter to ask what she and her family were doing on the day of colored eggs and Peeps. They were gathering at a friend’s house on the other side of town, she told me, with other longtime Portland friends, where all their children—most of them too old to be excited by the colored eggs but still committed to the Peeps—would have their annual spring romp. She asked if my partner and I wanted to come.

“Oh no,” I said. “We have plans.”

“What?” She sounded a little distracted, as if she might be in the middle of a conversation with one of the kids.

“Are you on speaker phone?”

She laughed. “No, it’s just me.”

“Well,” I said. “We’re doing Ecstasy for Easter.”

She laughed again, a startled hilarity that I figured would ripple through the day, hidden from the children, whispered to her husband and friends on the phone. She’d have a good story to take to the Easter gathering. Something she could pass around, like a tray of deviled eggs or mini-quiches.

We spent the first part of that Easter Sunday birding at our wonderful urban wildlife park, Oaks Bottom. It was a heavenly day for it—not so cold that we needed heavy jackets but before the trees were all leafed out, making it harder to see birds in the canopy. We spied many of our favorites—ruby-crowned kinglets, white-breasted nuthatches, wood ducks (both the male and the female so seductively feathered), a couple of green-winged teals, a western screech owl tucked in a tree cavity, blending so perfectly with the bark that we wouldn’t have seen her if we hadn’t known she would be there. And we saw our mammalian favorite, too, a mink who stared at us with what I like to imagine as familiar curiosity—“oh yeah, them again!”-- before streaking across the path and up the hill, a fierce and sprightly brown ribbon.

“Well,” I said. “We’re doing Ecstasy for Easter.” My daughter laughed, a startled hilarity that I figured would ripple through the day, hidden from the children, whispered to her husband and friends on the phone. She’d have a good story to take to the Easter gathering. Something she could pass around, like a tray of deviled eggs or mini-quiches.

My partner and I met only eight years ago, a week after the women’s marches following Trump’s first election. Like me, he had moved from somewhere else to live near a beloved daughter, and we each had two marriages in our past. OK Cupid said we had enough things in common to make a meeting worthwhile, so we agreed to meet at one of Portland’s ramen restaurants. I told him to wear his daughter’s pink pussy hat so that I’d be able to find him, but I’d forgotten when I arrived and wondered why the weirdo in the oddly knit beanie was grinning at me. After that was cleared up, I had a sudden thought that he looked like my sweet grandfather, another tall, angular man who died when he was many years younger than we were then, in our late 60s. We share ancestral goo—Catholicism, Irish and German grandparents, parents from small towns with the busy, cocktail-party lives of certain white middle-class people of the last century. We share a lot of passions and have discovered new ones together, like birding. Neither can believe our luck that we found the other.

We had planned to go home after birding and take Ecstasy, hoping to find a new glimmer to take us through the afternoon, evening and beyond. Like so many other people, we have read Michael Pollan’s How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence and other writings on psychedelics. We were intrigued by the idea of “shaking the snow globe” of our minds, curious about the new ideas and insights that might settle into place.

We’d both tried psilocybin a year before, in a family home at Lake Tahoe, with disappointing results—the wood grain on the ceiling pranced around and the cedar tree outside showed a kindly face, but I felt even more bitterly the loss of my parents and sister and niece, all of whom had once surrounded me in that house. My partner tried again six months later, with a so-called a hero’s dose of psylocibin along with Ecstasy, attended by a therapist. This time he wanted to do just the Ecstasy because he wanted more of the easy happiness it brought him. And he wanted me to have that feeling too, even though happiness is easier for me than for him. For Christmas, he gave me a couple of therapy-grade crystals for us to take together.

I kept putting it off. I had my apprehensions! Ecstasy hadn’t been a drug embraced by my demographic when we were young, plus generally I don't do drugs. Most of what people consider recreational drugs are hellish for me. Cannabis gives me hours of clench-jawed paranoia, and the one time I did hash (twenty years ago, in Afghanistan), I cowered in bed for hours, certain the house where I was staying was going to be raided because we had wine with dinner.

I thought of Ecstasy as a party drug and worried it might compel my partner and me to dance furiously in our living room all night—and heaven forbid, maybe even spill our frenzy into the street, a spectacle for the neighbors. It sounded exhausting and maybe even hazardous. I had to remind myself that I’m committed to embrace novelty and challenge—even foolishness—at this age, when it’s easy to be overly careful. When we finally planned to do it on Easter, I had a performance anxiety dream the night before: I was supposed to go ocean scuba diving with a group, but arrived late, after everyone else had been suited up and given their instructions. They left without me and some guy had the task of suiting me up, then I had to pee and take everything off again. He led me along dark city streets to catch up with the group but I lost him and wandered around in the gloom, tripping over my flippers, trailing the cables and tubes that would have connected me to a safety crew on the ocean surface. Easter morning I was both groggy and nervous.

We had planned to go home after birding and take Ecstasy, hoping to find a new glimmer to take us through the afternoon, evening and beyond. Like so many other people, we have read Michael Pollan’s How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence and other writings on psychedelics. We were intrigued by the idea of “shaking the snow globe” of our minds, curious about the new ideas and insights that might settle into place.

After we got home from birding, we swallowed our crystals and chewed the ginger candy the therapist had included to mask the taste, then settled down to play cribbage while we waited for the Ecstasy to take effect. I was playing well, for me, but then I found I lost interest in the scoring and, really, in doing anything at all. We went to our room and lay down in bed with the curtains partly closed. My partner put a lovely album by jazz saxophonist Charles Lloyd, Forest Flower, on repeat.

The experience was almost unbearably fizzy at first, like having a hive of friendly bees swarming inside my skin, but that settled down. I kept looking through the gap in the curtains, expecting that what I could see of the yard—the mock-orange shrub, the lesser goldfinches that kept landing and flitting away, the circling insects—would be distorted by the drug, but everything outside my body was normal. A breeze stirred the curtains and a thin bar of sunlight striped our closet door, rippling and winking from the movement outside—as dazzling as a marquis, but I understood this to be the everyday wonder of sunlight and wind, not something produced by the drug.

My own body was the wonder. It was as if in this ordinary room on this ordinary day, I had slipped into another dimension—an envelope hidden in the folds of ordinary life, suddenly revealed, where I was effortlessly happy and kind. I recalled what the woman with the bedtime podcast that I listen to during bouts of insomnia often says (to my slight, churlish irritation): You've done enough. You are enough. But that was how it felt in this newly accessible dimension: everything was enough, everything was plenty, all was well. My partner and I held hands and didn't talk much. I remember that I said, "It's so quiet." The drug, I meant, when I was expecting it to be boisterous. He said, “Wouldn’t this be good for everyone?” meaning the many hurting people we love and all those hurting others we don’t even know, and I said, Yes. Yes! But mostly we just let ourselves feel this lower-case ecstasy, attended by Charles Lloyd’s sly and gentle sax and the flickering beam of light on the closet door.

In our first year together, we did a lot of, “What if we had met back then?” Back when we were both young and roaming the streets of San Francisco with flowers in our hair? Back when we were newly single and passing through some other place—the Denver airport or a jazz club in New York or Sun Valley? We were mindful of the memories we were now making—a new shared past—from daily events like walking the dogs as well as big calendar events, like a fabulous trip to Portugal.

But we also know we might not have the time and the vigor to make a huge pile of memories. Friends and icons from our youth are falling around us. Our beautiful dogs—mine for thirteen years, his for seven—died last year, one suddenly and one after a heartbreaking two years of decline. We decided to get another dog and began the extraordinarily stringent adoption procedure with a pet rescue operation. My own mortality barked during a lengthy phone interview with the adoption coordinator. “I don’t mean any offense, Miss Kristin,” she said. “But who is going to take care of this dog if something happens to you?” Could it be that we were too old for a dog? What else might we be too old for?

The thing about the Ecstasy: it was a very short trip and it made powerful memories. It’s hard for me to re-experience the delight of wandering around Portugal, but not hard to remember and thrill to the nearness of that pocket of happiness, hidden in the folds of the ordinary. Not hard for me to take my partner’s hand and feel the bliss of just that. Sometimes in the car or house, his phone will send Charles Lloyd’s Forest Flower to the speaker system—I’m not sure if it’s randomly chosen by the phone or if he programmed it to light me up. Then I feel just like our new young husky, bounding through the woods and rolling on her back to invite the love.

Kristin Ohlson is a writer from Portland, Oregon. Her new book Sweet in Tooth and Claw: Stories of Generosity and Cooperation in the Natural World – which the Wall Street Journal calls “excellent and illuminating”--probes the mutually beneficial relationships among living things. Her last book was The Soil Will Save Us: How Scientists, Farmers and Foodies are Healing the Soil to Save the Planet, which the Los Angeles Times calls “a hopeful book and a necessary one…. a fast-paced and entertaining shot across the bow of mainstream thinking about land use.” She appeared in the award-winning documentary film, Kiss the Ground, to speak about the connection between soil health and climate health.

Ohlson’s articles have been published in the New York Times, Orion, Discover, Smithsonian.com, Gourmet, Oprah, and many other print and online publications. Her magazine work has been anthologized in Best American Science Writing and Best American Food Writing. https://www.kristinohlson.com

Okay, your turn…

How old are you? Have you taken Ecstasy, or other psychedelic drugs? Did you take them recreationally? What were the circumstances? Did you take them medicinally, under the guidance of a physician or other clinician? Was your experience with psychedelics positive? Negative? Neutral? Would you do them again? (If you’re commenting, please also do me the favor of hitting the heart button ❤️ for algorithmic purposes. Thank you!)

Big thanks to Kristin Ohlson. And to all of you—the most engaged, thoughtful, kind commenters I’ve ever encountered on the internet. And thank you, too, for all your encouragement and support. 🙏 💝 I couldn’t do this without you.

Older adults exploring psychedelics is a thing! I just finished writing a book called ELDEREVOLUTION - Psychedelics and the New Counterculture of Aging, which delves into this phenomenon (to be published next spring). Back in the day, boomers experimenting with pot and psychedelics envisioned a radical new youth culture. Fifty years later, we're reimagining older age - as a time of healing, growth, spiritual deepening and joy - as well as making peace with our mortality! Exciting stuff in these challenging times...

The two burly security guards outside the pot shop my son took me to in San Francisco were amused by this white-haired woman. One said, "Don't worry little momma, your boy's gonna take care of you." I had to tell them, "You kids didn't invent this shit and this ain't my first rodeo." The guards were likely stoned because they found this very funny.

Inside, the selection process with the sales person could have been a SNL skit. We chose some excellent, very mild products.

But I too remember that clench-jawed paranoia. And I bet many of us remember watching the sunset from a rooftop and knowing we could fly if we just reached out a schooch further. So lthough it's tempting, and I loved this essay, I won't be resuming recreational use of psychelidelics. I'm very happy the research, on hiatus for decades, has been resumed. It's so promising.