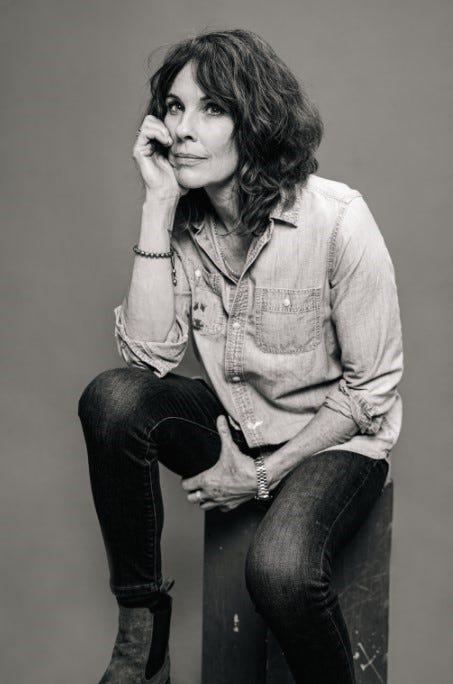

(Don't) Act Your Age

"Who ruled that I shouldn't be on a skateboard? Who decreed that this type of fun was over for me? I don't want to actually be younger..."

From Tough Broad: From Boogie Boarding to Wing Walking – How Outdoor Adventure Improves Our Lives as We Age by Caroline Paul, published by Bloomsbury Publishing. Copyright © 2024 by Caroline Paul. All rights reserved.

At every phase of your life, look at your options. Please, don't pick the boring ones.

Barbara Hillary, retired nurse, at 75 years old skied to the North Pole.

1. (Don't) Act Your Age

I’m at the entrance gate to Yosemite National Park, and the young ranger is shaking her head. She can’t let me drive in, she tells me, because the name on the paperwork I am proffering does not match my ID. Instead, it is of the friend who is entering at another gate, an hour from here. “Without her, I can't let your car into the park.” she says. I look for a sign that she will relent, but she is young and earnest and rules are rules.

“Do people walk?” I ask and the ranger looks alarmed and tells me it’s nine miles to the valley. Then I remember my Onewheel, fully charged to its 15-mile capacity and resting in the trunk, so I say, half joking and half desperate, “Well, can I get on my Onewheel?”

I can see by the ranger’s face that she doesn't understand so I add, “It's an electric skateboard,” and she blinks rapidly, taking in the staid hatchback with the sensible gas mileage, the gray roots of my hair, the thin veil of cat dander that may be rising from my shirt, and the 1963 birthdate on the ID. She repeats, electric skateboard? as if giving me time to tell her I'm not serious, but I just nod and she pulls her head back in the booth, then reappears moments later, and says that, um, sure, an electric skateboard is allowed.

"Okay, I'll be back," I say, and I watch her go momentarily still, as if already lost in the future of what she will compose on her social media feed—Lolz! Old Lady, on skateboard!!!?? I don't hold this against her; when I was her age I was exactly the same, dumping everyone over 50 unceremoniously into a box labeled Old, subdividing that further into just a few categories limited to adjectives like Frail, Ill, Senile, or Boring. Not to mention the big one: Dying. From my callow, know-it-all perspective, everyone over 50 was on the downhill slide to imminent death. There was definitely no file labeled Can Ride an Electric Skateboard. So, I don’t feel resentful, I feel delighted and even a little bit sorry for my young ranger, who doesn't realize that soon enough she will be where I am. Then she will upend her own expectations (I hope), maybe even remembering this encounter 30 years on.

When I was the young ranger’s age I was exactly the same, dumping everyone over 50 unceremoniously into a box labeled Old, subdividing that further into just a few categories limited to adjectives like Frail, Ill, Senile, or Boring. Not to mention the big one: Dying. From my callow, know-it-all perspective, everyone over 50 was on the downhill slide to imminent death.

For now, though, she is still certain that the world works in a particular way, and that this is some sort of misunderstanding. She pins the politeness back on her face and waves me around in a U-turn. I park my car a quarter mile down the mountain. I put on my wrist guards and my helmet and my fanny pack (because I may be a skateboarder but I am still 57 years old and believe in safety first and quick access to Chapstick). I remove my Onewheel from the trunk, switch it on, then step back, admiring it. It’s a balance board centered on one large wheel powered by electricity; consider it a Segway married to a snowboard, just another branch from the family tree atop which sits the mighty Skateboard. I put one foot on the rear side of the wheel and the other foot forward of it, push the board level, and suddenly I’m off, whizzing back up the winding road. I have a grin on my face because how could I not? I'm outside. The air is crisp. All the marginalia I did not see the first time around from my sitting position in my car unfurls around me—the Merced river heaves and roils, granite rocks as big as hippos stampede along the banks, trees flash yellow and orange.

I approach the gate again, and skirt the cars. Ahead lies those nine miles of windy mountain road, trod by horse, by stagecoach, by millions of automobiles and buses, yet surely territory rarely touched by skateboarders, certainly not by 57-year-old ladies on Onewheels. I zip toward a knot of rangers outside the hut and as they turn toward me one jettisons up her eyebrows as if she has spotted a black bear pawing, say, a lunch cooler—could be dangerous, don't do anything sudden, stay calm, the look says. Someone else laughs a little and they all stutter-step away from me as if I'm about to wipe out their entire squadron of youthful shins, but I stop and dismount without incident.

I’ve been riding my Onewheel since I was 52 and it's often like this: From a distance, and in my helmet and sunglasses (and now my Covid mask) I look like any teenager hurtling forward with fearsome abandon. But as I approach, and surge into closer focus, it becomes clear: I am your grandmother. Teenagers smirk and Millennials grow wide-eyed, their thoughts as obvious as if enshrined in a talk bubble over their full heads of hair and jowl-less chins: Wait, what? That's an OLD WOMAN.

Come on now, I'm not old. But at this moment, at the Yosemite gate, I am also not, by most cultural definitions, acting my age, and certainly not acting my gender; there might not be quite this kerfuffle if I were, say, an almost-60-year-old man. Yet who ruled that I shouldn't be on a skateboard? Who decreed that this type of fun was over for me? I don't want to actually be younger. I love my late fifties, finding in them a solidity of self, a peace of mind, a true happiness un-buffeted by the insecurities and tumult of earlier years: youth’s abject self-consciousness, hapless communication skills, and angst about everything ranging from appearance to sex to what everyone else is thinking. And yet, while riding the skateboard I do feel many things attributed to a younger generation: physically vital, confident, carefree, even a little bit reckless. Youth has claimed these things as their own, fully expectant that I am too fragile and perhaps incompetent (not to mention incontinent) to pursue these feelings, and certain that I no longer desire them at all. But they are wrong. I have been energized all my life by physical vitality, confidence, freedom, and risk. Why would I give it up now?

From a distance, and in my helmet and sunglasses I look like any teenager hurtling forward with fearsome abandon. But as I approach, and surge into closer focus, it becomes clear: I am your grandmother. Teenagers smirk and Millennials grow wide-eyed, their thoughts as obvious as if enshrined in a talk bubble over their full heads of hair and jowl-less chins: Wait, what? That's an OLD WOMAN.

Yet at some age—I’m not sure when and it probably lies within a range—many women believe that they can’t, or shouldn’t, be out there. Out there, as in the out-of-doors. Out there, as in a little bit unruly, a little off the beaten path. Out there, as in learning something new, or pushing physical comfort zones. I'm not speaking about freaky, hair-raising danger, or overwhelming stress. I'm talking a version of outdoor activity and adventure that fits the realities of our age but doesn't succumb to the falsehoods—that as older women we are fragile, possibly mentally dotty, certainly not qualified to do anything but take constant precautions.

But let’s face it, our biggest danger may not be a mountain bike, or a surfboard, or saying yes to a tandem skydive. Instead, the real peril for us as we age may be a sedentary life that lacks pizzazz and challenge. And I’m a lifelong adventurer. Surely, I can continue to defy societal messaging while also gracefully accepting the very real fact that my body is changing, that I am weaker, slower, creakier. Ultimately, I'm my best self in the outdoors—curious, brave, and present. That in turn gives me confidence and optimism. All these seem like character traits I should hold on to as I age.

Of course I’ve noticed changes. The obvious ones were physical. My body was stiff, and I was flummoxed by its softness. I was dismayed too by my face, which was sagging in all the expected ways. Like many women (and surely, men), I would look in the mirror and not really recognize myself. Inside, it is said, we all have an age, and mine was somewhere between 37 and 42. I couldn't square the strange commas around my mouth and the looseness of my neck with that internal person. But I was also curious. What parts of my old identity fit this new phase of my life? What aspects were simply vestigial habits from previous decades? I would need to look past the prevailing narratives and expectations about women aging to find out: can't we embrace this long, last phase of our life with excitement, wringing what is possible out of it, despite difficulties?

I believe that we can, and that the key may lie in a renewed relationship with outdoor adventure. With its physical vitality, its uncertainty, and its exhilaration, outdoor adventure upends our own limited expectations of ourselves at this age. But there’s more: we feel society’s gaze shift too.

Of course I’ve noticed changes. The obvious ones were physical. My body was stiff, and I was flummoxed by its softness. I was dismayed too by my face, which was sagging in all the expected ways. Like many women (and surely, men), I would look in the mirror and not really recognize myself. Inside, it is said, we all have an age, and mine was somewhere between 37 and 42. I couldn't square the strange commas around my mouth and the looseness of my neck with that internal person.

Back at the Yosemite toll booth, I accept a map that has been proffered and answer a few wide-eyed questions about the Onewheel. It is clear from their wonder and befuddlement that I have shaken up prejudgements. Yet, perhaps the young rangers have also deemed me harmless. I’m a one-time zoological curiosity, a far outlier on an otherwise neatly plotted bell curve.

But here’s what I haven’t told them.

The friend on my reservation, who I am meeting, is also in her fifties. And she would also give them pause. But much, much more pause. She is a BASE jumper, someone who habitually hucks herself from bridges, antennae, spans, and earth (thus the B-A-S-E of BASE jumpers). Tomorrow at dawn it will be earth, specifically the earth on the rim of Yosemite's fabled wall, El Capitan. This is, of course, very illegal; there is even a Yosemite Park jail for those caught doing this (as well as for those like myself who serve as accessories to their crimes). But right now, to the earnest, milling rangers, I am the antithesis of a future felon. I am an older white woman with a cockamamie hobby, and it is confirmed again that the reservation is needed for the car, not the human, and that I am free to continue on my, um, skateboard. I am sent off with genuine smiles and small shakes of the head. Then the young rangers turn back to their duties, naturally assuming that there will be no more surprises, that I am otherwise just another gal with a bird list and a picnic, meeting friends for a gawp around the valley. If they hear from me again, they are sure, it will be because my friend stopped her large sedan in the middle of the road and traffic piled up behind us: that’s the kind of ridiculous thing those older women do when they spot something flying in the wild, the young rangers have been told. They have no inkling that what might be flying in the wild is actually one of these older women. With no more thought, they wave the next car through.

Agreed! But many women stop way short of their actual limitations and give in to perceived ones. A big part of the book is about adapting - keeping the elements of adventure like exhilaration and exploration but dialing the actual logistics to suit the situation. I interview a 64 yar old bird watching in a wheelchair. I walked through a suburban park with a hiker. Your 80 will look different than my 60!

I love this! I have lived my life in awe of my great grandmother, who at 53 decided she would go to college with her youngest kid (my grandmother) ... she did, Oberlin was the only place that would let them in together! .... and she lived to be 98, became a poet/writer/professor at Berea College in KY, and was still riding her bike to do her errands until not long before she died! Had she known about one wheelers she would have had one.